8 Uterovaginal prolapse and urinary incontinence

Uterovaginal prolapse

Definition

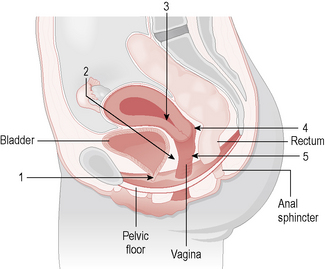

Uterovaginal prolapse is defined as descent of a pelvic organ or structure into and sometimes outside the vagina. ‘Prolapse’ can be taken as meaning pelvic organ prolapse, urogenital prolapse, genital prolapse, rectocele/cystocele/urethrocystocele, vaginal vault prolapse and uterine descent (Fig. 8.1).

Anatomy of the pelvic floor

• Level 1 (upper third of the vagina) support consists of endopelvic fascial tissue that condenses laterally as the cardinal (transverse cervical) ligaments and posteriorly as the uterosacral ligaments.

• Level 2 (middle third of vagina) support attaches the middle portion of the vagina to the arcus tendineus and fascia of the levator ani muscles.

• Level 3, the lower vagina, is supported predominantly by connections to fibres of the pelvic diaphragm and the perineal membrane.

Types of prolapse

1. First-degree, in which there is descent of the cervix into the vagina but not as far as the introitus.

2. Second-degree, in which the cervix reaches the introitus.

3. Third-degree, in which the cervix and body of the uterus lie outside the introitus (this is also known as procidentia).

Vault prolapse is eversion of the vault of the vagina that can occur after hysterectomy.

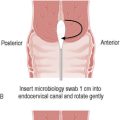

Examination

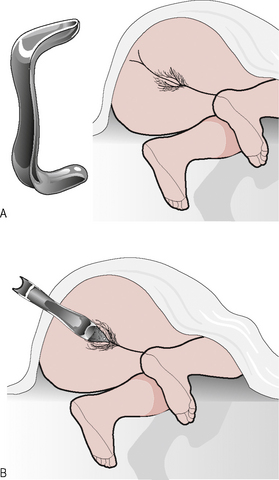

Abdominal examination should always be performed to exclude any masses or organomegaly. The woman should first be examined in the dorsal position when she is asked to bear down, strain or cough, during which inspection of the introitus should reveal any obvious second- or third-degree prolapse; stress incontinence may be demonstrated and atrophy may be apparent. Examination is then performed with the patient in the Sims’ position (patient in left lateral position with chest at 45°∞ to the examining couch, the left leg straight, the right hip extended and knee flexed) with a Sims’ speculum, which allows full inspection of the uterine prolapse and vaginal walls (Fig. 8.2). The blade of the Sims’ speculum is inserted along the posterior wall of the vagina and retracted in order to display the anterior wall, with the patient bearing down. The anterior wall can be supported with sponge forceps to assess for apical descent (cervix or vault) and then the anterior vaginal wall is supported in order to assess the posterior wall, with the patient bearing down. Vaginal examination is performed in the usual manner with assessment of the uterus and adnexae as previously outlized and any obvious descent of the cervix or prolapse of the vaginal walls noted. In the research setting and increasingly in specialist centres, a system called pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POPQ) can be utilized. This is a complex nine-point assessment of uterovaginal prolapse, which describes four stages of pelvic organ descent relative to the hymenal ring.

Treatment

Conservative measures

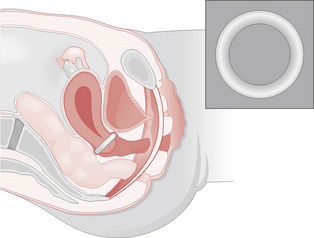

Many types of pessaries have been developed for vaginal and uterine support, although surgical correction should be considered whenever possible. A typical plastic ring pessary should comfortably rest between the posterior fornix and the symphysis pubis, thereby supporting and stretching the vaginal wall, preventing vault prolapse and directly supporting any cystocele present (Fig. 8.3). Pessaries need to be replaced 6-monthly to avoid infection or ulceration of the vagina. Pelvic floor re-education or strengthening is best achieved under the direction of a trained continence advisor or by a physiotherapist using directed muscle exercises or weighted vaginal cones that the woman must try to retain within the vagina. Sometimes this can be combined with electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor muscles, which has also been shown to be of benefit.

Surgical procedures

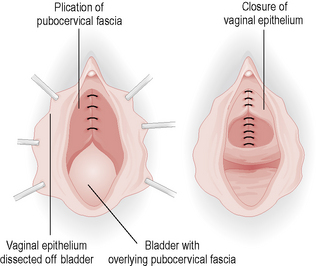

Anterior repair (colporrhaphy) is a procedure that repairs fascial defects in the anterior vaginal wall and removes the excess vaginal skin that results from the prolapse (Fig. 8.4). This can also include the use of a supporting suture (buttress) under the urethra. Complications are uncommon, although postoperative voiding difficulties may occur and recurrence of prolapse occurs in up to 50% of patients.

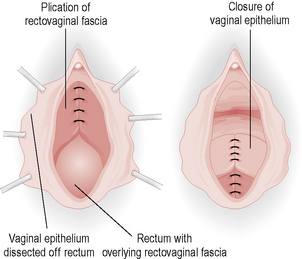

Posterior colpoperineorrhaphy is a repair of the posterior wall prolapse, which involves repair of rectovaginal fascial defect and approximation of the levator ani muscles medially to support the rectum with removal of the excess vaginal skin (Fig. 8.5).

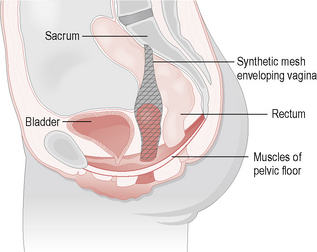

Vault prolapse can be corrected via either an abdominal (sacrocolpopexy) (Fig. 8.6) or vaginal (sacrospinous ligament fixation) procedure. The latter involves suturing the vault to the sacrospinous ligament. Both these techniques are effective, but the vaginal route has less immediate postoperative morbidity. Both techniques of vault fixation can cause either posterior or anterior (respectively) wall prolapse in the long term.

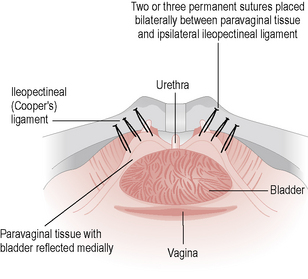

It is worth noting that some anti-incontinence procedures, in particular a Burch colposuspension (Fig. 8.7), may also cure a cystocele, especially if done in conjunction with a paravaginal repair.

Urinary incontinence

Assessment

History

• Incontinence – how often does it occur, is it a daily problem, what is its impact on quality of life? Attempt to quantify leakage in terms of pad usage per day which, although subjective, is useful as an outcome measure of treatment

• Stress incontinence – leakage on exercise, walking, lifting or coughing. Establish which of these manoeuvres provoke incontinence

• Urgency or urge incontinence

• Nocturia (night-time voiding, in particular waking from sleep to void)

• Dysuria, bladder pain or haematuria

• Voiding dysfunction, e.g. poor stream, incomplete emptying

• Bladder stimulants, e.g. caffeine, alcohol, medications

• Past history – obstetric history, age at menopause, medical problems, surgery.

Examination

• General examination, including weight and urinalysis

• General gynaecological – evidence of excoriation as a result of chronic urinary leakage, atrophic vaginal changes and evidence of demonstrable stress incontinence during Valsalva manoeuvres

• Prolapse – careful evaluation of prolapse as outlined earlier, including use of a Sims’ speculum. In particular, a large cystocele may actually kink the urethra during Valsalva, preventing stress incontinence, but give rise to overflow incontinence or overactive bladder symptoms as a result of voiding difficulty. Also, a large rectocele may occlude the urethra during Valsalva, so that correction of this or the large cystocele may unmask a tendency to stress incontinence (occult stress incontinence)

• Local neurological examination, in particular, assessing for deficit in the areas innervated from the S2–4 nerve roots.

Overactive bladder

Management

• Propantheline is an inexpensive drug that is useful, but prone to the anticholinergic side effects of constipation, dry mouth and blurred vision. Propiverine is a newer alternative.

• Oxybutynin has both anticholinergic and smooth-muscle relaxant properties and is now available in a once-daily extended-release preparation or as a transdermal patch.

• Tolterodine may be better as it has been shown to reduce significantly the number of micturitions in 24 hours and also the number of incontinence episodes, as well as having fewer of the anticholinergic side effects. A newer variant is now available, called fesoterodine, that bypasses hepatic metabolism. Solifenacin is an alternative anticholinergic.

• Imipramine is particularly useful for the treatment of nocturia, nocturnal enuresis and intercourse incontinence.

• DDAVP is useful in the treatment of nocturia and enuresis. It is given intranasally by spray at night. Recently a tablet form has become available.

Stress incontinence

Management

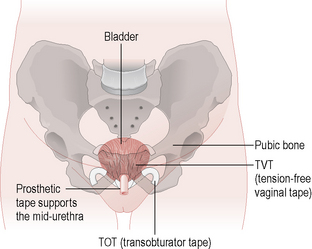

Surgery is performed when conservative measures have failed and the patient’s quality of life is compromised. The options depend on the patient’s fitness for anaesthesia and whether any other prolapse exists. Burch colposuspension was the gold-standard procedure, with a success rate of 85–90%. The retropubic space is entered through a small suprapubic incision and two or three permanent sutures are placed on either side of the bladder neck to the corresponding ileopectineal ligament (see Fig. 8.7). This procedure can also be performed laparoscopically. There are a variety of ‘sling’ procedures that can be performed abdominally or vaginally, with rectus sheath, fascia lata or synthetic materials. The commonest type is the tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedure (Fig. 8.8), which has the advantage that it can be performed under local anaesthesia. It has success rates of between 80 and 90% and has taken over from the Burch procedure as the gold-standard treatment for USI. An alternative method of placing the mid urethral sling is via the obturator foramen and this technique is also proving an effective alternative to TVT. Anterior colporrhaphy with bladder buttress is rarely performed for stress incontinence as it has cure rates of less than 50%.

Management

• Midstream specimen of urine – these patients often have a urinary tract infection because of large urinary bladder residuals, which may require prophylactic antibiotic treatment.

• Intravenous pyelogram (IVP) – ureteric reflux may result from the bladder hypotonia.

• Urodynamics – flow studies will show a reduced flow rate with a strain or interrupted sinusoidal pattern. Cystometry will show a delayed first sensation, reduced detrusor pressure during voiding in hypotonia, or conversely, a high detrusor pressure with urethral obstruction.

Summary

• Take a careful history of uterovaginal prolapse, bladder and bowel functions, and sexual activity.

• Accurate history and examination are crucial to making a correct diagnosis and assessing impact on quality of life so that an appropriate treatment strategy is commenced.

• Urodynamic investigation must be performed prior to any anti-incontinence surgery.

• Conservative management should always be offered and predisposing factors such as obesity, chronic cough, constipation and pelvic masses should be improved if possible.

• Great care should be taken in selecting the appropriate surgery for each individual patient. Remember that stress incontinence can be unmasked following surgical correction of prolapse.

• Careful counselling of patients prior to surgery regarding complications and success rates should be given.