Chapter 38 Uterovaginal displacements, damage and prolapse

UTERINE DISPLACEMENTS

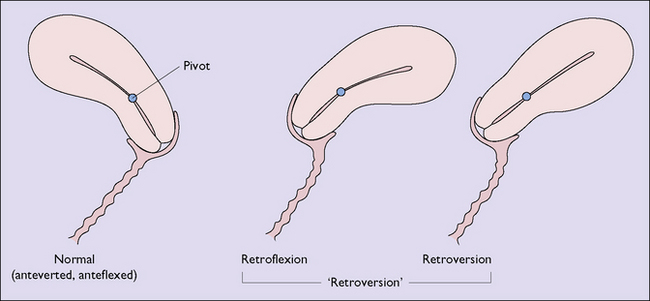

The uterus is an organ that normally pivots about an axis formed by the cardinal ligaments at the level of the internal cervical os. In 90% of women the uterus is anteflexed and anteverted, lying on the urinary bladder and moving backwards as the bladder fills. In 10% of women the uterus is retroflexed and may be retroverted (Fig. 38.1). This is a developmental occurrence. The uterus is mobile and can be moved by inserting a finger in the posterior vaginal fornix. In spite of anecdotal statements, a mobile retroverted uterus is not a cause of infertility, abortion or backache.

Diagnosis

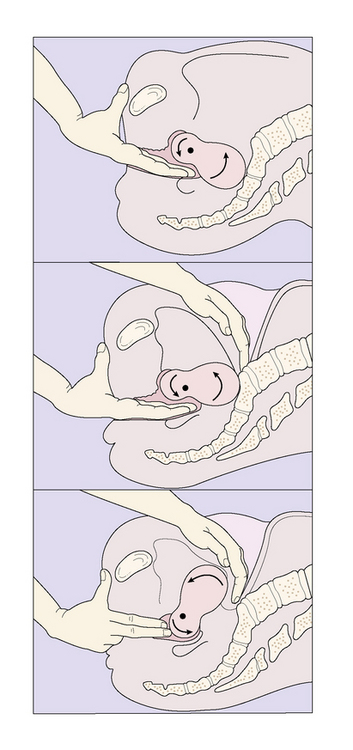

A clinical finding that the uterus is retroverted and is accompanied by symptoms should alert the medical practitioner to determine whether the retroversion can be corrected by manipulation (Fig. 38.2). If it can, it is not the cause of the symptoms. If it cannot be manipulated it may be the cause of the symptoms.

UTEROVAGINAL DAMAGE AND INJURIES

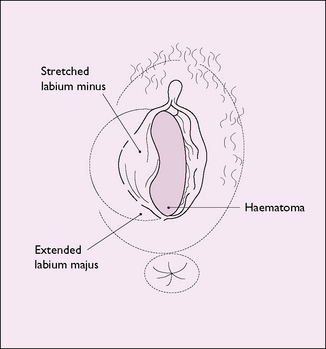

Injury to the vulvovaginal area may occur, for example if a girl or woman falls astride some object or is kicked. The vagina may be damaged or a haematoma may form in the vulva (Fig. 38.3). Injury may also occur if a young girl or a postmenopausal woman is sexually assaulted.

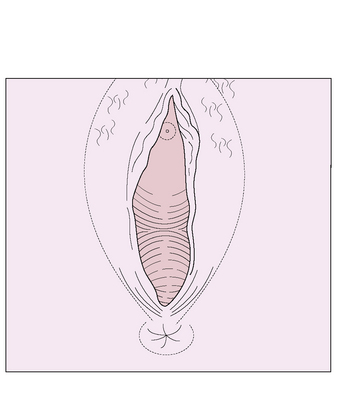

Injury resulting from childbirth is discussed on page 81. Occasionally a vaginal tear is not sutured immediately, and the woman attends a medical practitioner some time later. On inspection the vaginal entrance is seen to gape and the perineal muscles are separated (Fig. 38.4). The woman may complain that water enters her vagina when she bathes, or that vaginal flatus occurs.

Cervical damage may occur during rough cervical dilatation. The laceration is usually small, but may extend from one or other lateral angle of the external cervical os. This may cause marked bleeding. Cervical damage may also occur during childbirth and is discussed on pages 81, 82.

GENITAL TRACT FISTULAE

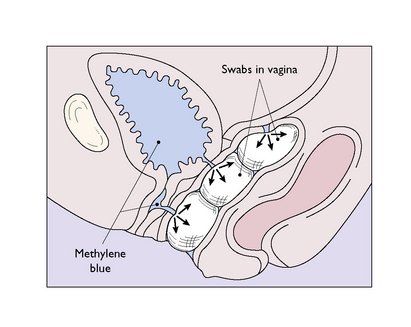

Obstetrical and surgical fistulae occur immediately after the procedure or 5–14 days after the operation, when the traumatized ischaemic tissue sloughs. The woman complains of continuous leakage of urine in cases of a vesicovaginal fistula, or faeces in the case of a rectovaginal fistula. If the fistula is large it can be seen on vaginal inspection with a Sims speculum, the woman lying in the left lateral position. Small fistulae may require tests to pinpoint the damaged area. One such test is shown in Figure 38.5. Small vesicovaginal fistulae may close spontaneously if the bladder is drained continuously for 14 days, but rectovaginal fistulae and larger fistulae require surgery.

UTEROVAGINAL PROLAPSE

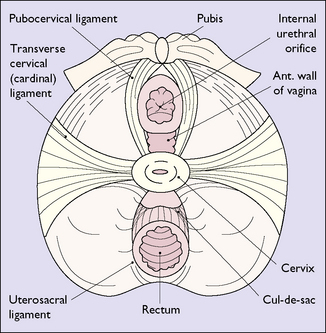

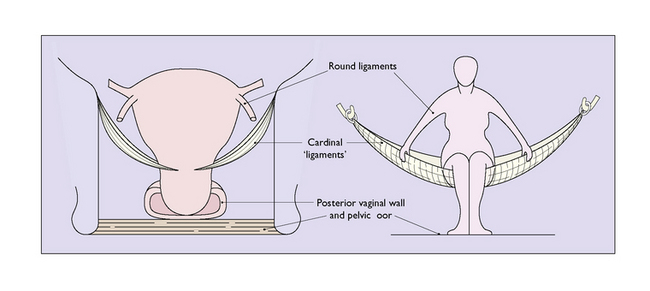

Acting in conjunction, these supports prevent uterine prolapse (Fig. 38.8). However, this state of affairs may be altered if the supports are stretched during childbirth. This may occur if the woman tries to expel the fetus before the cervix is fully dilated, strains for a long time in the second stage of labour, or if undue force is used to expel the placenta. In these circumstances the cardinal ligament may be stretched, making a uterine prolapse more likely. In consequence, prolapse is more common in women who have had several children and are obese.

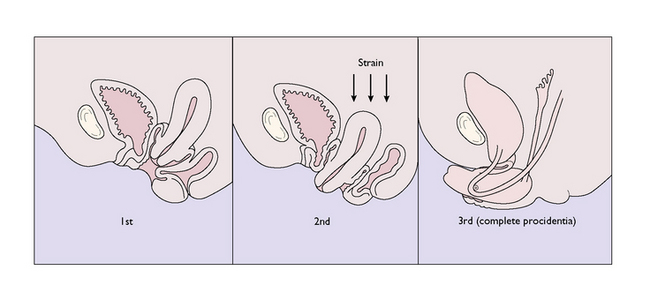

Degrees of uterine prolapse

For descriptive purposes uterovaginal prolapse is divided into three degrees of increasing severity (Fig. 38.9). In each of these the cervix elongates and may become congested or oedematous. When the cervix protrudes from the vagina, as in the third degree of prolapse, the cervical epithelium becomes dry and its superficial layers are keratinized.

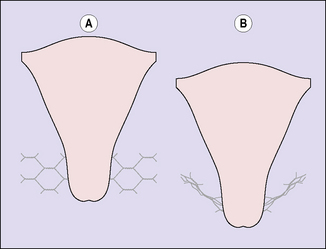

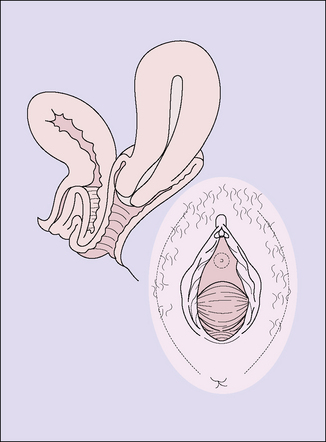

Prolapse of the anterior vaginal wall (cystocele)

This occurs during childbirth, when the fibres of the levator ani muscle, which supports the vagina, are stretched. The weakened anterior vaginal wall bulges into the vagina, bringing the adjacent bladder with it (Fig. 38.10).

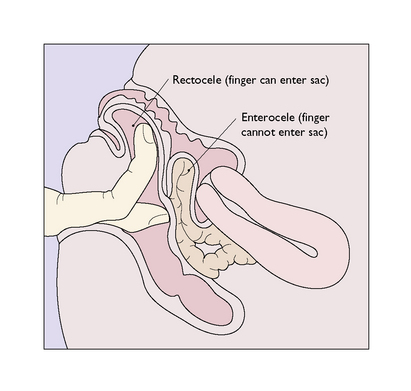

Prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall (rectocele)

With diminished support, the posterior vaginal wall, together with the anterior rectal wall, bulges into the vagina (Fig. 38.11).

Treatment

Treatment depends on the age of the woman, her desire to have further children, and the degree of the prolapse. Younger women with mild degrees of symptomless prolapse can delay treatment until the prolapse worsens or the menopause is reached. They should be taught pelvic floor exercises (see p. 311), which alone may control the symptoms. It is preferable not to treat a prolapse surgically if the woman wishes to have a further child, as the delivery must then be by caesarean section to avoid damage to the repair. If the woman has a cystocele, a midstream urine sample should be taken to exclude bacteriuria. If the urine is sterile, surgery is not required unless the woman desires it. She should be checked periodically.