Chapter 41 Uterine Corpus Cancer

Epidemiology and Etiology

Epidemiology and Etiology

The median age for endometrial cancer is about 58 years. The risk factors associated with the development of carcinoma of the endometrium are listed in Box 41-1. Any factor that increases the exposure to unopposed estrogen increases the risk for endometrial cancer. If the proliferative effects of estrogen are not counteracted by a progestin, endometrial hyperplasia and possibly adenocarcinoma can result.

Symptoms

Symptoms

The most common symptom of endometrial cancer is abnormal vaginal bleeding, which is present in 90% of patients. Postmenopausal bleeding is always abnormal and must be investigated. The most common conditions associated with postmenopausal bleeding are listed in Table 41-1. In the premenopausal patient, especially after age 35 years, menorrhagia or intermenstrual bleeding may signal an endometrial malignancy.

| Factor | Approximate Percentage |

|---|---|

| Exogenous estrogens | 30 |

| Atrophic endometritis, vaginitis | 30 |

| Endometrial cancer | 15 |

| Endometrial or cervical polyps | 10 |

| Endometrial hyperplasia | 5 |

| Miscellaneous (e.g., cervical cancer, uterine sarcoma, urethral caruncle, trauma) | 10 |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

STAGING

The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) changed from a clinical to a surgical staging system for endometrial cancer in 1988. The new surgical staging, based on pathologic confirmation of the extent of spread, is shown in Table 41-2.

TABLE 41-2 International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) STAGING OF ENDOMETRIAL CARCINOMA (1988)

| Stage Ia | Tumor limited to endometrium |

| Stage Ib | Invasion through less than half of the myometrium |

| Stage Ic | Invasion equal to or more than half of the myometrium |

| Stage IIa | Endocervical glandular involvement only |

| Stage IIb | Cervical stroma invasion |

| Stage IIIa | Tumor invades serosa or adnexa or both, or positive peritoneal cytologic findings, or both |

| Stage IIIb | Vaginal metastases |

| Stage IIIc | Metastases to pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes, or both |

| Stage IVa | Tumor invasion of bladder or bowel mucosa, or both |

| Stage IVb | Distant metastases including intraabdominal or inguinal lymph nodes, or both |

| Histologic grade does not change the stage | |

| Grade 1 | Well differentiated |

| Grade 2 | Moderately differentiated |

| Grade 3 | Poorly differentiated |

Pathologic Features

Pathologic Features

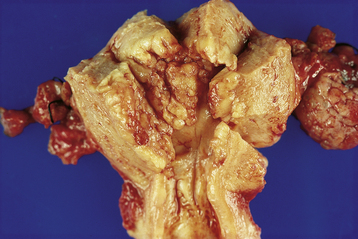

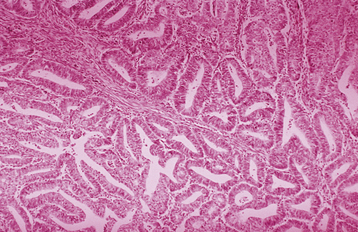

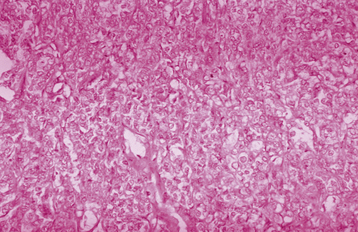

Invasive adenocarcinoma of the endometrium demonstrates proliferative glandular formation with minimal or no intervening stroma. Tumor grade is determined by both the degree of abnormality of the glandular architecture and the degree of nuclear atypia. A lesion that is well differentiated (grade 1) forms a glandular pattern similar to normal endometrial glands (Figure 41-1). A moderately well-differentiated lesion (grade 2) has glandular structures admixed with papillary, and occasionally solid, areas of tumor. In a poorly differentiated lesion (grade 3), the glandular structures have become predominantly solid with a relative paucity of identifiable endometrial glands (Figure 41-2).

Treatment

Treatment

STAGE I

Surgery

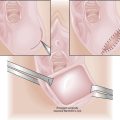

An exploratory laparotomy with total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is performed on all patients, unless there are absolute medical contraindications (Figure 41-3). On opening the abdomen, peritoneal washings are taken with normal saline for cytologic evaluation. About 15% of patients with disease confined to the corpus have positive peritoneal cytology. Retroperitoneal spaces should be opened and evaluated, and any enlarged pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes should be resected. Formal surgical staging, including at least pelvic lymphadenectomy, should be performed on high-risk patients, including those with serous, clear cell, or grade 3 histology; outer-half myometrial invasion; or cervical extension. Laparoscopic surgery, including laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, with or without laparoscopic lymph node dissection, is being increasingly used, particularly for obese patients, and those with grade 1 or 2 cancers.

Radiation Therapy

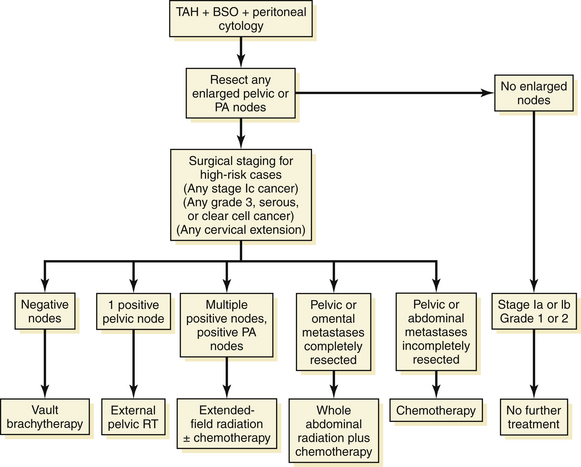

Recommendations are as follows (Figure 41-4).

ADVANCED STAGES

For advanced disease, treatment is individualized. The uterus, tubes, and ovaries should be removed, if possible, for palliation of bleeding and other pelvic symptoms. If gross disease is present in the upper abdomen, tumor metastases that are readily removable, such as an omental “cake,” should be extirpated in an attempt to improve the patient’s quality of life by temporarily decreasing abdominal discomfort and ascites. In addition, patients with advanced disease also require chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or both, as shown in Figure 41-4.

RECURRENT DISEASE

Prognosis

Five-year survival rates for each stage of endometrioid endometrial cancer are presented in Table 41-3.

TABLE 41-3 SURVIVAL FOR ENDOMETRIAL CANCER BY FIGO STAGE (N = 5694)

| Stage | No. of Patients | Five-Year Survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Ia | 1063 | 91.1 |

| Ib | 2735 | 89.7 |

| Ic | 1219 | 81.3 |

| IIa | 364 | 78.7 |

| IIb | 426 | 71.4 |

| IIIa | 484 | 60.4 |

| IIIb | 73 | 30.2 |

| IIIc | 293 | 52.1 |

| IVa | 47 | 14.6 |

| IVb | 160 | 17.0 |

Data from the Annual Report on the Results of Treatment in Gynecological Cancer. Patients treated 1996-1998. J Epidemiol Biostat 83:79-118, 2003.

Uterine Sarcomas

Uterine Sarcomas

Aalders J.G., Thomas G. Endometrial cancer—revisiting the importance of pelvic and paraaortic lymph nodes. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;104:222-231.

Hacker N.F. Endometrial cancer. In Berek J.S., Hacker N.F., editors: Practical Gynecologic Oncology, 5th ed, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009.

Leath C.A.III, Huh W.K., Hyde J., et al. A multi-institutional review of outcomes of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;105:630-634.

Lee N.K., Cheung M.K., Shin J.Y., et al. Prognostic factors for uterine cancer in reproductive-aged women. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:655-662.

Parazzini F., La Vecchi C., Bocciolone L., Franceschi S. The epidemiology of endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1991;41:1-16.

Prat J., Gallardo A., Cuatrecasas M., Catasus L. Endometrial carcinoma: Pathology and genetics. Pathology. 2007;39:1-7.

Secord A.A., Havrilesky L.J., Bae-Jump V., et al. The role of multi-modality adjuvant chemotherapy and radiation in women with advanced stage endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;107:285-291.

Screening of Asymptomatic Women

Screening of Asymptomatic Women Signs

Signs Preoperative Investigations

Preoperative Investigations

Pattern of Spread

Pattern of Spread