Chapter 18 Using standardised tools

Despite the current lack of a standardised rating scale that can be used on a regular basis by a general mental health clinician for a wide variety of presentations, it would be remiss not to recognise that the rating scales that are available are of immense use and importance in many areas of mental health work. Furthermore, as understanding of risk factors for specific risks has been increased and refined, the development of standardised rating scales has advanced. Within a forensic environment, standardised rating scales are used extensively.

Standardised rating scales were initially developed within forensic environments to provide a highly structured format to facilitate the assessment of violence. These scales raise an ‘index of suspicion’ of risk whilst clinical skills allow the context and other factors to be incorporated into a meaningful formulation. Standardised rating scales are the means for assessing which risk factors have relevance for particular risks and have applications in both research and everyday clinical life. ‘They enable the clear articulation of the basis for specific estimates of future risk and can clarify sources of disagreement where these occur.’1 These scales can form an important part of risk management processes when used in conjunction with clinical assessment, although there are disadvantages (as described on page 63). Standardised rating scales draw on research evidence of factors known to be associated with the identified risk. Note should be made once more of the limited usefulness in everyday clinical practice of standardised rating scales that do not include dynamic factors. Scales that limit themselves to static risk factors are of some use in prediction of risk at a population level but have limited place in care of individual patients.

For the general mental health clinician:

… the initial risk assessment exercise should consist of a structured process of more or less standard questions aimed at eliciting factors increasing the risk (and which will reflect the evidence base around the risk) and which assists clinical judgment. It could be called an aide-memoire or a framework. After the clinician addresses these standard questions, it will be possible to determine whether a more in-depth assessment is needed using existing, evidenced-based toolkits for the particular population.2

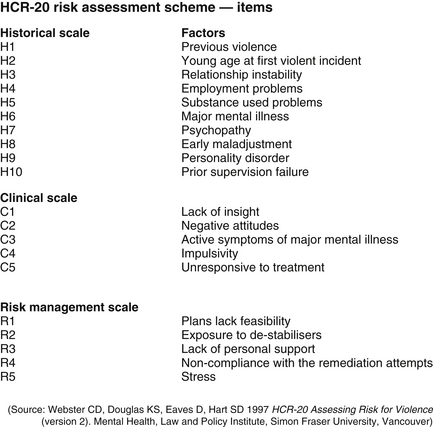

There is no one toolkit which fits all patients and covers all risks. A list of toolkits can be found in Appendix 1 of the UK Department of Health document entitled ‘Best Practice in Managing Risk’ (2007).3 New toolkits have been published, including the ‘Forensicare Risk Assessment and Management Exercise’ (FRAME),4 in an attempt to incorporate a standardised tool into case management and psychiatric treatment. As yet, for the risks of suicide and self-harm, there is no instrument with a sufficiently strong evidence base.5 However, Bouch and Marshall (2005) have suggested a useful tool which is worth considering.6 The most commonly used scale for the assessment of risk of violence on which several of the newer scales are based — the HCR-207 — was published in 1997 and has been widely used throughout Canada, America, Europe and Australasia. It is included here (Figure 18.1) to give an idea of what a scale looks like. Within a forensic setting, there is value to be had from applying the HCR-20 at various stages during a patient’s treatment as the clinical and risk scores can alter substantially during treatment. Each item is coded on a three-point scale (‘absent’, ‘possibly present’ or ‘definitely present’). Most of the items in the HCR-20 have been included in the list of risk factors for violence (Table 9.2, page 83–84). Many of them are also included as prompts in the risk form used throughout this book.

To apply the HCR-20 requires prior training, but when used regularly it can be a useful tool to help plan further treatment. The HCR-20 is useful in forensic psychiatry but is much less suitable for general adult psychiatry and is unsuitable for the risk posed by children or by adults with intellectual disabilities.8

Using standardised scales to predict violence in inpatient settings

Although standardised scales were developed to predict violence in the longer term, interest has focussed recently on predicting violence in inpatient settings. Several studies have looked at the accuracy of violence predictions on inpatient units. Research has looked at using scales at the time of admission and easily repeated scales during admission. This work is helping move the use of rating scales away from the time-consuming operations previously required towards simpler scales that are able to be used by all clinicians with little training needed.

One study9 found that violence on an inpatient ward was best predicted by:

• violence in the week preceding hospitalisation

• general psychopathology score on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale10

The last item was the best single predictor. By creating an actuarial prediction model, the researchers were able to correctly identify whether 84% of their sample would exhibit violence during the hospitalisation with a positive predictive power of 80%. This could be used as a simple check at the time of admission.

Another more recent study11 utilised another quickly applied scale; the Broset Violence Checklist (BVC-CH). This rates six patient behaviours — confusion, irritability, boisterousness, verbal threats, physical threats and attacks on objects — combined with a subjective visual analogue scale. They reported a substantially reduced rate of violence over the 45 913 hospitalisation days studied.

Another scale studied is the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression (DASA:IV)12 which includes both dynamic and situational factors.

The DASA:IV assesses the following items:

This can be used to assess risk of imminent aggression on a day-to-day basis.13 These three studies are important not just because of the usefulness of the rating scale, but also because they promote a climate of risk assessment and management in an environment where violence is not uncommon.

BOX 18.1 STANDARDISED RATING SCALES

• Help identify risk factors of relevance for specific risks.

• Can be used in inpatient settings to review risk of violence.

• Are more commonly used in forensic settings.

• Generate the risk factors to be used in structured clinical assessments of risk.

• When used serially, can be an effective measure of change in level of risk.

Further reading on inpatient rating scales

Daffern M. The predictive validity and practical utility of structured schemes used to assess risk for aggression in psychiatric inpatient settings. Aggression and Violent Behaviour. 2007;12:116–130.

Doyle M., Dolan M. Predicting community violence from patients discharged from mental health services. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;189:520–526.

1 Carroll A. Are violence risk assessment tools clinically useful? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;41:301–307.

2 Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008 Rethinking Risk to Others in Mental Health Services. Final report of a scoping group. Royal College of Psychiatrists College Report CR 150, June.

3 Department of Health. Best Practice in Managing Risk. Principles and Evidence for Best Practice in the Assessment and Management of Risk to Self and Others in Mental Health Services. Document prepared for the National Mental Health Risk Management Programme. London: Department of Health; 2007.

4 Carroll A. Risk assessment and management in practice: the Forensicare Risk Assessment and Management Exercise. Australasian Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):412–4117.

5 Department of Health, above, n 3.

6 Bouch J., Marshall J.J. Suicide risk: structured professional judgment. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2005;11:84–91.

7 Webster C.D., Douglas K.S., Eaves D., Hart S.D. HCR-20 Assessing Risk for Violence (version 2). Vancouver: Mental Health, Law and Policy Institute, Simon Fraser University; 1997.

8 Royal College of Psychiatrists, above, n 2.

9 Arango C., Barba A.C., Gonzalez-Salvador T., Ordonez A.C. Violence in inpatients with schizophrenia; a prospective study. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1999;25:493–503.

10 The PANSS, or the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, is a rating scale used for measuring symptom severity of patients with schizophrenia.

11 Abderhalden C., Needham I., Halfens R., Haug H., Fischer J.E. Structured risk assessment and violence in acute psychiatric wards: randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;193:44–50.

12 Ogloff J.R.P., Daffern M. The Assessment of Inpatient Aggression at the Thomas Embling Hospital: Towards the Dynamic Appraisal of Inpatient Aggression. Forensicare, Victorian Institute of Forensic Mental Health Fourth Annual Research Report to Council; 2003. 1 July 2002–30 June 2003.

13 Barry-Walsh J, Daffern M, Duncan S, Ogloff J 2009 The prediction of imminent aggression in patients with mental illness and/or intellectual disability using the Dynamic Appraisal of Situational Aggression instrument. Australian Psychiatry, vol 17 no 6.