20 Urticaria and Angioedema

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Urticaria is characterized by the waxing and waning appearance of pruritic, erythematous papules or plaques with superficial swelling of the dermis (Figure 20-1). The swelling observed with urticaria and angioedema results from the movement of plasma from small blood vessels into adjacent connective tissue. Unlike atopic dermatitis, the pruritus of urticaria is driven by histamine. Histologically, urticarial lesions consist of a lymphocyte-predominant perivascular infiltrate. In CIU, the cellular infiltrate is similar to that seen in allergen-induced late phase skin response, and the cytokine profile is both TH1 and TH2.

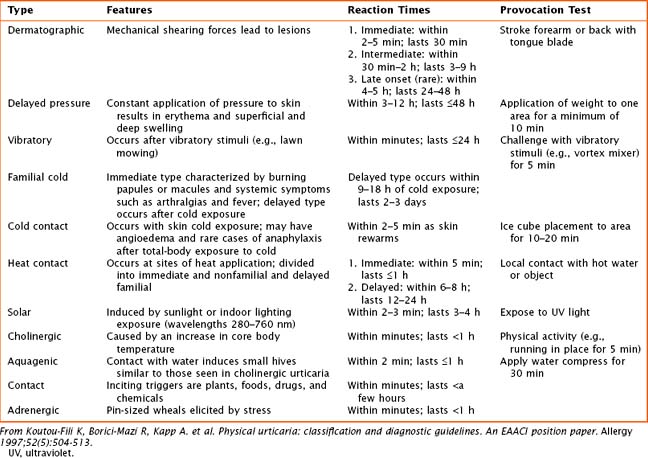

Physical Urticaria

Physical urticarias have a specific trigger that directly induces hives within minutes, with hives lasting minutes to a few hours. Physical urticarias are further classified into multiple subtypes (Table 20-1), each having a different physical trigger; thus, an individual can have more than one subtype. Mast cell degranulation is included in the pathogenesis of most subtypes of physical urticaria, including dermatographic, cholinergic, cold, and solar urticaria, but serum immunoglobulin may also be involved as demonstrated by passive transfer experiments.

Angioedema

Angioedema, which is a swelling of the dermis, subcutaneous, and submucosal tissues, often coexists with urticaria but typically persists past 24 hours (Figure 20-2). Angioedema is described as painful or burning in quality. The lack of pruritus in angioedema may be caused by fewer mast cells in the lower dermis and subcutis. Idiopathic angioedema coexists with urticaria, occurring in up to 50% of those with CIU. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors can also trigger angioedema via the bradykinin pathway.

Clinical Presentation

Patients with long-lasting lesions or the presence of other systemic symptoms should be evaluated for other diseases (see Box 20-1). Urticarial vasculitis is classified by painful or pruritic lesions lasting longer than 48 hours and may leave residual skin changes unrelated to excoriation. Concurrent systemic complaints or abnormal laboratory findings indicative of an inflammatory process, such as an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP) or low complement levels, are seen. A skin biopsy is required to rule out urticarial vasculitis. Urticaria pigmentosa, a subset of mastocytosis, may mimic urticaria, although these lesions are typically pigmented and last longer than urticaria. The presence of fever with urticaria can occur in Schnitzler’s syndrome and Muckle-Wells syndrome. Schnitzler’s syndrome is described as recurrent urticaria with arthralgia, fever, and elevation in inflammatory markers in association with an elevation in IgM. Muckle-Wells syndrome is a periodic fever syndrome with urticaria associated with periodic, unexplained fevers.

Box 20-1 Differential Diagnosis of Urticaria and Angioedema

History

In diagnosing either acute or chronic urticaria, a thorough history is the most important element along with a detailed physical examination. The history should elicit the time of onset of hives (because some patients may experience diurnal variation) and the specific days that the patient is affected because there may be an association with certain environmental exposures or stressors. A description of the lesions, including their shape, size, distribution, color, pigmentation, and the quality of pain or itch, is important in confirming the diagnosis of urticaria. To identify acute triggers, the history should elicit recent use of medications, including antibiotics, nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and aspirin; food ingested shortly before symptom occurrence (especially within 2 hours of lesion appearance); implanted surgical devices; insect stings; and changes in environment. Questions regarding recent infections or to evaluate for symptoms of thyroid disease are important (see Chapter 68). For female patients, it is important to investigate if there is a variation of hives in relation to hormonal changes observed with menses or pregnancy. Physical triggers are important for defining physical urticarias. Further evaluation of life stressors may assist in understanding the timing of lesions. It is also important to evaluate how the patient is coping and what therapeutics, including nonprescription medications or dietary changes, are being used and if they are providing any relief. Some patients with chronic urticaria are on restricted diets, which are unnecessary and may lead to nutritional deficits. Medication side effects should also be evaluated.

Physical Examination

The physical examination is important in solidifying the diagnosis of urticaria, but it cannot distinguish between acute and chronic urticaria. The examination should focus on the size, distribution, and color of the lesions. Whereas wheals are characteristically pink or red because of histamine-induced dilatation of vessels in the skin and are easily blanched, vasculitic lesions have a darker red or purple appearance resulting from vascular damage and leakage. Cholinergic urticaria has a characteristic “fried egg” appearance with a small wheal and surrounding large flare (Figure 20-3). The physical examination should include testing for dermatographism, which can be elicited by applying linear pressure to skin using a blunt object, such as a tongue depressor. In some types of physical urticaria, eliciting urticaria with additional maneuvers is diagnostic, as in the ice-cube test for cold urticaria. The physical examination should include thyroid palpation to assess for thyroid gland abnormalities.

Brodell LA, Beck LA. Differential diagnosis of chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2008;100:181-188.

Dibbern DA, Dreskin SC. Urticaria and angioedema: an overview. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:141-162.

Greaves MW. Chronic urticaria in childhood. Allergy. 2000;55:309-320.

Kaplan AP. Clinical practice. Chronic urticaria and angioedema. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:175-179.

Kaplan AP. Urticaria and angioedema. In: Adkinson NF, Bochner BS, Busse WW, et al, editors. Middleton’s Allergy: Principles and Practice. ed 7. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2008:1063-1075.

Kaplan AP, Greaves M. Pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:777-787.