Chapter 211 Urticaria

Diagnostic Summary

Diagnostic Summary

• Urticaria (hives): Well-circumscribed erythematous wheals with raised serpiginous borders and blanched centers that may coalesce to become giant wheals; limited to the superficial portion of the dermis.

• Angioedema: Eruptions similar to those of urticaria but with larger well-demarcated edematous areas that involve subcutaneous structures as well as the dermis.

• Chronic versus acute: Recurrent episodes of urticaria and/or angioedema of less than 6 weeks’ duration are considered acute, whereas attacks persisting beyond this period are designated chronic. When no underlying cause is found, chronic urticaria is referred to as chronic idiopathic urticaria.

• Special forms: Special forms have characteristic features—dermographism, cholinergic urticaria, solar urticaria, cold urticaria.

Introduction

Introduction

Urticaria and angioedema are relatively common conditions: It is estimated that they occur in 15% to 25% of the general population.1 Although persons in any age group may experience acute or chronic urticaria and/or angioedema, young adults (postadolescence through the third decade of life) are most often affected.2,3

The basic pathophysiology of urticaria involves the release of inflammatory mediators from mast cells or basophilic leukocytes, both of which have high-affinity receptors for immunoglobulin E (Ig E).4 Although this inflammation classically occurs as a result of IgE–antigen complexes interacting with these cells, other non–IgE-mediated mechanisms are probably also critical in many patients with urticaria, including prostaglandins, leukotrienes, cytokines and chemokines. A growing body of evidence shows that at least 40% of patients with chronic idiopathic urticaria have clinically relevant functional autoantibodies to the high-affinity IgE receptor on basophils and mast cells. The term autoimmune urticaria is used for this subgroup of patients presenting with continuous ordinary urticaria.5

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology

The signs and symptoms of acute and chronic urticaria show consistent patterns despite the many diverse etiologic and initiating factors (see later) that have been found, yet the pathogenesis cannot be entirely ascribed to any one mechanism. However, at present, it appears that mast cells and mast cell–dependent mediators play the most prominent role in the pathogenesis of urticaria.6

Mast cells are widely distributed throughout the body and are found primarily near small blood vessels, particularly in the skin. The granule-containing mast cell is a secretory cell capable of releasing both preformed and newly synthesized molecules, termed mediators. These mediators (listed in Box 211-1) play key roles in the pathogenesis of both immunologic and nonimmunologic inflammatory reactions. The three distinct sources of mediators are as follows:

• Preformed mediators, which are contained in the granules and are released immediately

• Secondarily formed mediators, which are generated immediately or within minutes by the interaction of the primary mediators and nearby cells and tissues

• Granule matrix–derived mediators, which are preformed but slowly dissociate from the granule after discharge and remain in the tissues for hours

BOX 211-1 Mast Cell–Derived Mediators

• Eosinophil chemotactic factors of anaphylaxis (ECF-A)

• Eosinophil chemotactic oligopeptides

• Neutrophil chemotactic factor

• Exoglycosidases (β-hexosaminidase, β-δ-galactosidase,* β-glucuronidase)

• Slow-reacting substances (SRS-A): leukotrienes (LT) C, LTD, LTE

• Monohydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETEs)

• Hydroperoxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HPETEs)

Preformed, granule-associated:

Data from Keahey TM. The pathogenesis of urticaria. Dermatol Clin 1985;3:13-28.

The most common immunologic mechanism is mediated by IgE.

Helicobacter pylori has been implicated as a causative agent in chronic urticaria. However, two reviews of the trials showing the benefit of H. pylori eradication in patients with chronic urticaria have arrived at conflicting conclusions, one saying the benefit is weak and another that it is statistically significant.7,8 Including testing for H. pylori seems reasonable; if positive, a decision to proceed with this management should be considered carefully in the context of relative harms/burdens and benefits as well as patient values and preferences.

Causes of Urticaria

Causes of Urticaria

Fundamental to the treatment of urticaria is the recognition and control of causative factors.

Physical Urticarias

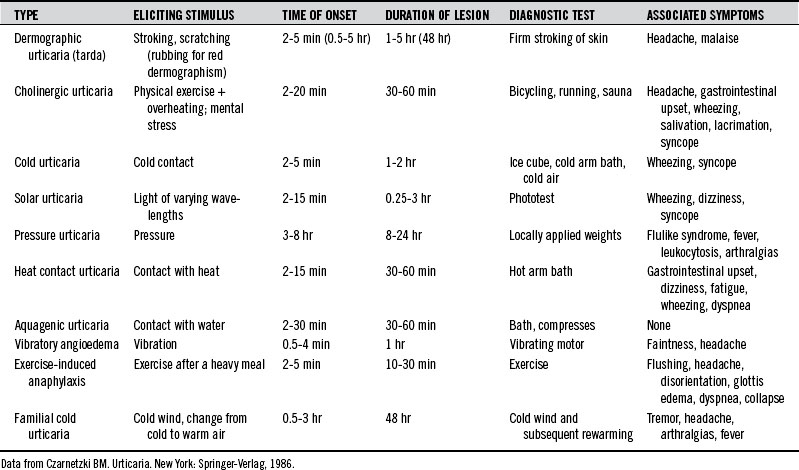

Urticaria can be produced as a result of reactions to various physical stimuli. The most common forms of physical urticarias are dermographic, cholinergic, and cold urticarias (Table 211-1). These are briefly described here. Less common types of physical urticarias or angioedema are as follows2:

Cholinergic Urticaria

A variety of systemic symptoms may also occur, suggesting a more generalized mast cell release of the mediators than in the skin. Headache, periorbital edema, lacrimation, and burning of the eyes are common symptoms. Less common symptoms are nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, dizziness, hypotension, and asthma attacks.2

Cold Urticaria

Cold urticaria is an urticarial and/or angioedematous reaction of the skin when it comes into contact with cold objects, water, or air. Lesions are usually restricted to the area of exposure and develop within a few seconds to minutes after the removal of the cold object and rewarming of the skin. The lower the object’s or element’s temperature, the faster the reaction. Children with cold urticaria have a higher risk of anaphylaxis, especially triggered by swimming.9

Widespread local exposure and generalized urticaria can be accompanied by the following symptoms:

Cold urticaria has been observed to accompany a variety of clinical conditions, including the following1:

The association of cold urticaria with infectious mononucleosis is well established. Other conditions associated with cold urticaria are cryoglobulinemia and myeloma, in which cold urticaria may precede the diagnosis by several years.2

Autoimmune Urticaria

Although much remains unknown regarding the specific pathophysiologic mechanisms underlying most cases of chronic urticaria, a minority seem to have an autoimmune basis. Research has discovered that a significant percentage of patients previously categorized as having idiopathic urticaria have autoantibodies to IgE or the FcεRIα subunit of the high-affinity IgE mast cell receptor.10 Studies have identified these autoantibodies in 24% to 76% of patients with chronic urticaria. From a clinical perspective, these patients tend to have a somewhat more severe, prolonged course of disease. Middle-aged women are disproportionately represented in the population of patients with urticaria, and higher rates of autoimmunity in this group, particularly for thyroid disease, may account for this preponderance. Thyroid autoantibodies are found more frequently in patients with these IgE receptor autoantibodies (see later discussion of thyroid).

Autoimmune diseases are well known to be associated with bowel permeabilities.11–14 Because subclinical impairments of small bowel enterocyte function have been postulated to induce a higher sensitivity to histamine in the digestive tract,15 it makes sense from a naturopathic standpoint to treat overt and subclinical digestive system permeabilities to decrease systemic inflammatory responses to endotoxins in these autoimmune conditions.

Drugs

Drugs make up the leading cause of urticarial reactions in adults. In children, the reactions are usually due to foods, food additives, or infections.2

Most drugs are composed of small molecules incapable of inducing antigenic/allergenic activity on their own. Typically, they act as haptens that bind to endogenous macromolecules, ultimately causing the production of hapten-specific antibodies. Alternatively, drugs can interact directly with mast cells to induce degranulation. Many drugs have been shown to produce urticaria. Box 211-2 provides a condensed list.16 The two most common urticaria-inducing drugs, penicillin and aspirin, are briefly discussed here.

BOX 211-2 Drugs That Can Cause Urticaria

Data from Andrews GC. Andrews’ diseases of the skin, ed 7. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1982:131.

Penicillin

Antibiotics, including penicillin and related compounds, are the most common cause of drug-induced urticaria. The allergenicity of penicillin in the general population is thought to be at least 10%. Nearly 25% of these individuals display urticaria, angioedema, or anaphylaxis on ingestion of penicillin.2,17

An important characteristic of penicillin is that it cannot be destroyed by boiling or steam distillation. This is a problem because penicillin and related contaminants can exist undetected in foods. To what degree penicillin in the food supply contributes to urticarial reactions is not known. However, urticaria and anaphylactic symptoms have been traced to penicillin in milk,18 soft drinks,19 and frozen dinners.20 In one study of 245 patients with chronic urticaria, 24% had positive skin test results and 12% had positive results on the radioallergosorbent test for penicillin sensitivity.21 Of those 42 patients sensitive to penicillin, 22 experienced clinical improvement with a dairy-free diet, whereas only 2 out of 40 patients with negative skin test results experienced improvement with the same diet. This study would seem to provide indirect evidence of the importance of penicillin in the food supply in urticaria.

In an attempt to provide direct evidence, penicillin-contaminated pork was given to penicillin-allergic volunteers. No significant reactions were noted other than transient pruritus in two volunteers.22 Penicillin in milk appears to be more allergenic than penicillin in meat.18 Presumably the reason is that penicillin can be degraded into more allergenic compounds in the presence of carbohydrate and metals, suggesting that penicillin in milk may be more allergenic than artificially contaminated meat.18

Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Antiinflammatory Drugs

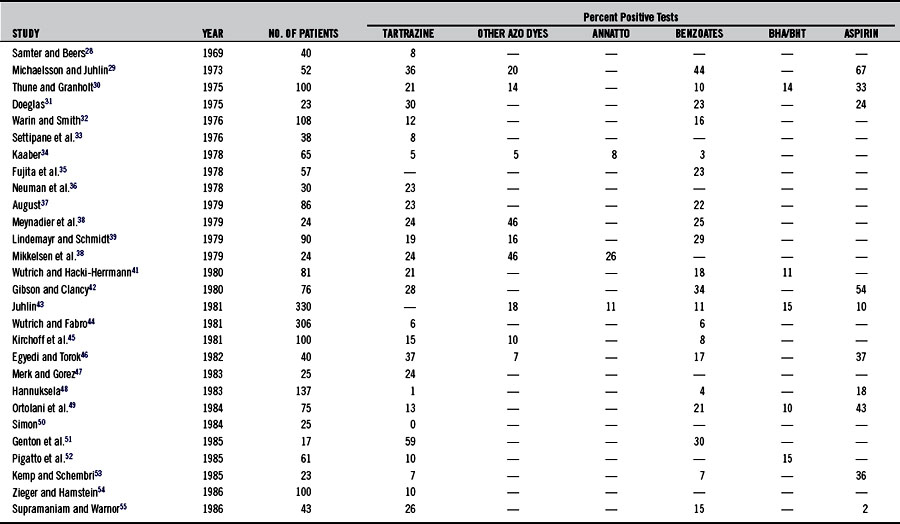

Urticaria is a more common indicator of aspirin sensitivity than is asthma (see Chapter 147). The incidence of aspirin sensitivity in patients with chronic urticaria is at least 20 times greater than that in normal controls.23–27 Studies (summarized in Table 211-2)28–57 have demonstrated that 2% to 67% of patients with chronic urticaria are sensitive to aspirin.

Aspirin inhibition of cyclooxygenase apparently shunts eicosanoid metabolism toward leukotriene synthesis, thereby increasing smooth muscle contraction and vascular permeability. In addition, aspirin and other nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have been shown to increase gut permeability dramatically and may alter the normal handling of antigens.53,58 NSAIDs are also known be associated with prolonged and more pronounced autoreactivity in urticaria.57 The daily administration of 650 mg of aspirin for 3 weeks has been shown to desensitize patients with urticaria and aspirin sensitivity. While taking the aspirin, patients also became nonresponsive to foods to which they usually reacted, such as pineapple, milk, egg, cheese, fish, chocolate, pork, strawberries, and plums.59 Others have noted this effect in patients with asthma, but they have also found that the effect disappears within 9 days after the treatment is stopped, suggesting the loss of effect or a possible placebo response.60

Food-Related Causes

Food Allergy

IgE-mediated urticaria can occur on the ingestion of a specific reaginic antigen. Although any food can be the agent, the most common offenders are milk, fish, meat, eggs, beans, and nuts.2,17,61–67 Other allergens are citrus, kiwis, peanuts, and apples.61 Individuals with atopy are most likely to experience urticaria as a result of IgE-related mechanisms, although reports confirm the presence of pseudoallergic reactions, whereby direct mast cell histamine release is involved in this reactivity. Aromatic volatile ingredients in tomatoes, wine, and culinary herbs (basil, fenugreek, cumin, dill, ginger, coriander, caraway, turmeric, parsley, pepper, rosemary, and thyme) have been considered the initiating factors in some of these non-IgE events.68,69

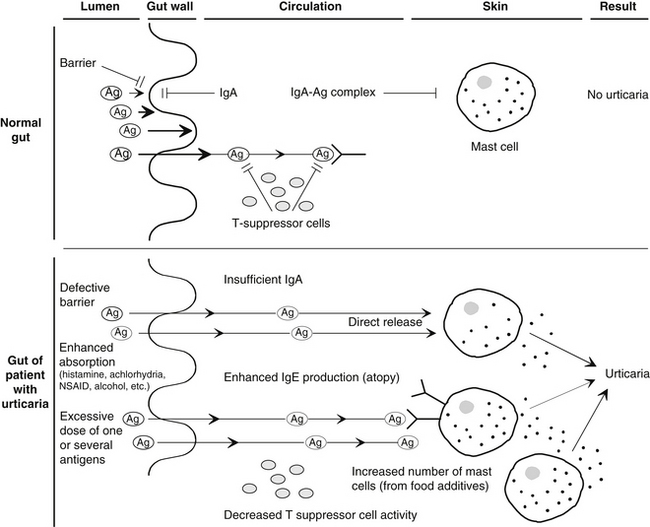

Food allergies may contribute greatly to the increased permeability of the gut in urticaria. A basic requirement for the development of a food allergy is the absorption of the allergen through the intestinal barrier. Several factors are known to significantly increase gut permeability, including alcohol, NSAIDs, vasoactive amines ingested in foods or produced by bacterial action on essential amino acids, and possibly many food additives (see Chapter 20 for a full discussion). Gut permeabilities are also associated with autoimmune conditions.11–14 Because chronic urticaria is now known to be at least partially related to an autoimmune process (see earlier discussion of autoimmune urticaria), it is possible that, depending on the genetic susceptibility of individual, these bowel permeabilities may play a key role in the instigation of immune activity and its prolongation, leading to chronic urticaria.

In addition, several investigators have reported alterations in gastric acidity, intestinal motility, and the function of the small intestine and biliary tract in up to 85% of patients with chronic urticaria.70–74 Selective IgA deficiency, gastroenteritis, hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria, and other disruptive factors reported in patients with chronic urticaria may temporarily or permanently alter the barrier and immune function of the gut wall, predisposing an individual to allergic sensitization.

In one study of 77 patients with chronic urticaria, 24 (31%) were diagnosed as achlorhydric and 41 (53%) were shown to be hypochlorhydric.72 Treatment with hydrochloric acid and a vitamin B complex gave impressive clinical results, highlighting the importance of correcting any underlying factor in the treatment of chronic urticaria (see Chapter 24).

Although IgE-mediated reactions are thought to predominate in immunologic urticaria, it has been suggested that IgG-mediated reactions are probably responsible for the majority of adverse reactions to foods, as seen in general practice (see Chapter 54). IgG antigen-antibody complexes are capable of promoting complement activation and the subsequent generation of anaphylatoxins that promote mast cell degranulation. This could be a significant factor in some cases of urticaria.

Figure 211-1 summarizes the basic aspects of a hypothetical model of immune defense in the normal gut and the urticarial gut.

Food Colorants

Food additives are a major factor in many cases of chronic urticaria in children. Colorants (azo dyes), flavorings (salicylates, aspartame), preservatives (benzoates, nitrites, sorbic acid), antioxidants (hydroxytoluene, sulfite, gallate), and emulsifiers/stabilizers (polysorbates, vegetable gums) have all been shown to produce urticarial reactions in sensitive individuals.*

The importance of the control of food additives was well demonstrated in a study of 64 patients with common urticaria. After 2 weeks on an additive-free diet, 73% of the patients had a significant reduction in symptoms. The diet strictly forbade preservatives, dyes, and antioxidants. No fruits or refined sugars were allowed except honey. Rice, potatoes, and unprocessed cereals were allowed, as well as fresh milk.75

Tartrazine

In 1959, the azo dye tartrazine (Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act [FD&C] Yellow no. 5) was the first food dye reported to induce urticaria.76 Tartrazine is one of the most widely used colorants. It is added to almost every packaged food as well as many drugs, including some antihistamines, antibiotics, steroids, and sedatives.77 Reactions to this food additive are so common that its use has been banned in Sweden.78

In the United States, the average daily per capita consumption of certified dyes is 15 mg, of which 85% is tartrazine. Among children, consumption is usually much higher. Tartrazine sensitivity has been calculated as occurring in 0.1% of the population.79

Tartrazine sensitivity is extremely common (20% to 50%) in individuals sensitive to aspirin.17,77 Like aspirin, tartrazine is a cyclooxygenase inhibitor and a known inducer of asthma, urticaria, and other allergic conditions, particularly in children. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase by tartrazine or aspirin apparently shunts eicosanoid metabolism toward leukotriene synthesis, thereby increasing smooth muscle contraction and vascular permeability.

In addition, tartrazine, as well as benzoate and aspirin, increases the production of the lymphokine leukocyte inhibitory factor.79 This results in an increase in perivascular mast cells and mononuclear cells. Histologic examination of patients with urticaria shows that more than 95% have an increase in perivascular mast cells and mononuclear cells.80

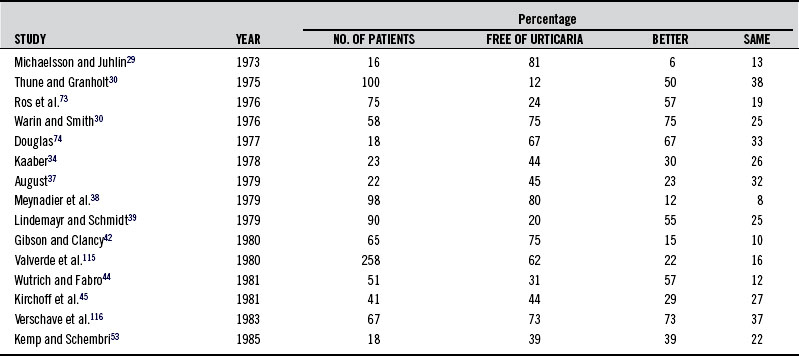

Table 211-2 summarizes the findings in studies using provocation tests to determine sensitivity to tartrazine and other food additives in patients with urticaria. Rates have varied from 5% to 46%. Diets eliminating tartrazine as well as other azo dyes and food additives in sensitive individuals have in many cases been shown to be of great benefit. These studies are summarized in Table 211-3. Table 211-4 shows a recommended test battery.81

TABLE 211-4 Test Battery for Patients With Recurrent Urticaria

| DAY | SUBSTANCE(S) TESTED | AMOUNT (MG) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Control (lactose) | 100,000 |

| 2 | Azo dyes: | |

| Tartrazine | 0.1, 1, 10 | |

| New coccine | 0.1, 1, 10 | |

| Sunset yellow | 0.1, 1, 10 | |

| 3 | Control (lactose) | 100, 100 |

| 4 | Benzoates: | |

| Sodium benzoate | 50, 500 | |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 50, 200 | |

| 5 | Carotene | 50, 100, 100 |

| Canthazanthine | 10, 200, 200 | |

| 6 | Annatto | 5, 10 |

| 7 | BHT-BHA | 1, 10, 50, 50 |

| 8 | Yeast extract | 600 |

| 9 | Control (lactose) | 100, 100 |

| 10 | Aspirin | 0.1, 1, 10, 100, 250, 500 |

| 11 | Sorbic acid | 50, 200, 200 |

| 12 | Control | |

| 13 | Sodium nitrite | 100 |

| Sodium nitrate | 100 | |

| 14 | Sodium glutamate | 100, 200 |

| 15 | Quinoline yellow | 1, 5, 10 |

| 16 | Potassium metabisulfate | 1, 5, 10, 50 |

Food Flavorings

Salicylates

A broad range of salicylic acid esters are used to flavor foods such as cake mixes, puddings, ice cream, chewing gum, and soft drinks. The mechanism of action of these agents is thought to be similar to that of aspirin.17

Salicylates are also found naturally in many foodstuffs. It is estimated that daily salicylate intake from foods is in the range of 10 to 200 mg/day.82 Because this is very close to the level of salicylates used in clinical testing (usually 300 mg), dietary salicylate may be a significant factor in aspirin-sensitive individuals.

Most fruits, especially berries and dried fruits, contain salicylates. Raisins and prunes have the highest amounts. Salicylates are also found in appreciable amounts in candies made of licorice and peppermint. Moderate levels of salicylate are found in nuts and seeds. Vegetables, legumes, grains, meat, poultry, fish, eggs, and dairy products typically contain insignificant levels of salicylates. Salicylate levels are especially high in some herbs and condiments, including curry powder (turmeric), paprika, thyme, dill, and oregano. Although the intake of these herbs and spices is relatively small, they can make a contribution to total dietary salicylate.82

Food Preservatives

Benzoates

Benzoic acid and benzoates are the most commonly used food preservatives. Although the incidence of adverse reactions to these compounds is thought to be less than 1% for the general population, the frequency of positive challenges in patients with chronic urticaria varies from 4% to 44%, as illustrated in Table 211-2.

Butylated Hydroxytoluene and Butylated Hydroxyanisole

Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and butylated hydroxyanisole are the primary antioxidants used in prepared and packaged foods. Typically, 15% of patients with chronic urticaria test positive to oral challenge with BHT.30,43,52,56 The use of chewing gum containing BHT was enough to induce urticaria in one patient.84

Sulfites

Sulfites, like tartrazine, have been shown to induce asthma, urticaria, and angioedema in sensitive individuals.85,86 The source may be varied, because these compounds are ubiquitous in foods and drugs. They are typically added to processed foods to prevent microbial spoilage and keep them from browning or changing color. The earliest known use of sulfites was in the treatment of wines with sulfur dioxide by the Romans. Sulfites are sprayed on fresh foods such as shrimp, fruits, and vegetables. They are also used as antioxidants and preservatives in many pharmaceuticals. Sulfites have caused such a wide range of health problems, such as asthma and urticaria, that their use on fresh fruits and vegetables (except potatoes) was banned in the United States in 1986.78

The average person consumes an average of 2 to 3 mg/day of sulfites. Wine and beer drinkers typically consume up to 10 mg/day, and individuals who frequent restaurants for meals may ingest up to 150 mg/day.85

Normally, the enzyme sulfite oxidase metabolizes sulfites to safer sulfates, which are excreted in the urine. People with a poorly functioning sulfoxidation system, however, have an increased ratio of sulfite to sulfate in their urine. Sulfite oxidase depends on the trace mineral molybdenum. Although most nutrition textbooks list molybdenum deficiency as uncommon, an Austrian study of 1750 patients found that 41.5% were molybdenum deficient.87

Food Emulsifiers and Stabilizers

A variety of compounds is used to emulsify and stabilize many commercial foods to ensure that the solids, oils, and liquids do not separate out. Most of the foods containing these compounds are heterogeneous, because they usually contain antioxidants, preservatives, and dyes. Polysorbate in ice cream has been reported to induce urticaria, and vegetable gums such as acacia, gum arabic, tragacanth, quince, and carrageenan may also induce urticaria in susceptible individuals.17

Infections

Infections are a major cause of urticaria in children.2 Apparently, in adults, immunologic tolerance occurs to many microorganisms owing to repeated massive antigen exposure. The role of bacteria, viruses, and yeast (C. albicans) in urticaria is briefly reviewed here. Chronic Trichomonas infections have also been found to cause urticaria.

Bacteria

As noted previously, H. pylori has been implicated in chronic urticaria. Bacterial infections contribute to urticaria in two other major settings—acute streptococcal tonsillitis in children and chronic dental infections in adults. In the first setting, acute urticaria predominates, whereas in the second, chronic urticaria predominates.2

Viruses

Hepatitis B is the most common cause of virally induced urticaria. One study found that 15.3% of patients with chronic urticaria had anti–hepatitis B surface antibodies.88 Urticaria has also been strongly linked to infectious mononucleosis and may develop several weeks before clinical manifestations. The incidence of urticaria during infectious mononucleosis is 5%.2

Candida albicans

The association between C. albicans and chronic urticaria has been suggested in several clinical studies. The number of patients with chronic urticaria who react positively to an immediate skin test with Candida antigens is 19% to 81%, compared with 10% to 15% of normal subjects.32,89–95 It appears that sensitivity to C. albicans is an important factor in at least 25% of patients with chronic urticaria.92 Approximately 70% of patients with a positive skin reaction also react to oral provocation tests using foods prepared with yeasts.

Treatment with nystatin has demonstrated that elimination of the organism can achieve a cure in a number of individuals with positive skin test results, although a placebo response cannot be ruled out. However, more patients have responded to a “yeast-free” diet than to simple elimination of the organism in clinical trials. The yeast-free diet employed excluded breads, buns, sausage, wine, beer, cider, grapes, sultanas, marmite, Bovril, vinegar, tomato, ketchup, pickles, and prepared foods containing food yeasts. For example, in a study of 49 patients with proved sensitivity to Candida, 9 showed responses to a 3-week course of nystatin, whereas 18 became symptom free only after adopting the yeast-free diet.92 This finding would seem to support the importance of diet along with elimination of the yeast.

Further support for the importance of diet can be found in a study of 36 patients with a positive skin-prick test response to Candida. Only 3 patients became asymptomatic with nystatin alone, compared with 23 with diet therapy after the nystatin therapy.93

Desensitizing patients to C. albicans with the use of a Candida cell wall extract has also demonstrated encouraging results in some patients, although the treatment of these individuals also included increasing gastrointestinal fermentation and acidity as well as elimination of yeast.94,95

Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic Considerations

Psychological Aspects

In one retrospective study involving 236 cases of chronic urticaria, psychological factors, such as stress, were reported to be the most common primary cause.96 Stress appears to play an important role through a reduction of intestinal secretory IgA levels.

In one study of 15 patients with chronic urticaria, relaxation therapy and hypnosis were shown to provide significant benefit.97 Patients were given an audiotape and asked to use the relaxation techniques described on the tape at home. At a follow-up examination 5 to 14 months after the initial session, 6 patients were free of hives and 7 others reported improvement.

Ultraviolet Light Therapy

Ultraviolet light has been shown to be of some benefit to patients with chronic urticaria.98,99 Both ultraviolet A and ultraviolet B light therapies have been used. Patients with cold, cholinergic, and dermographic urticarias display the greatest therapeutic response.

Thyroid

The association of thyroid disease and autoimmunity with urticaria has been established for decades.100–105 The prevalence of antithyroid antibodies in the normal population has been estimated at 3% to 6%, and they are commonly found in association with other autoimmune conditions, such as pernicious anemia and vitiligo.103 A subset of patients with chronic urticaria may be best helped by suppressing thyroiditis, by thyroid hormone therapy (as described in the following studies), by surgery, or by antithyroid medication.

One study evaluated a group of 624 patients with presumed idiopathic chronic urticaria and angioedema. From these, 90 patients were found to have thyroid autoimmunity.104 Forty-six of these patients were treated with L-thyroxine therapy, 8 of whom had remission within 4 weeks of therapy. Four patients with high thyroid antibody titers had repeated exacerbations when therapy was discontinued and had repeated remissions when therapy with L-thyroxine was resumed. Although in most cases treatment with L-thyroxine did not improve the patient’s urticaria or angioedema, a few did demonstrate a dramatic response.

Another study reported that thyroid hormone replacement therapy dramatically improved chronic urticaria in patients who had normal thyroid function but had evidence of thyroid autoimmunity. Of 7 patients with chronic urticaria, 5 were started on thyroid hormone; doses were increased in 2. Their urticaria resolved within 2 to 4 weeks, at which time the thyroid therapy was discontinued. In 5 patients, the symptoms returned within 4 weeks, then resolved within 4 weeks of restarting the hormone therapy. Antithyroid antibodies did not correlate with clinical response.104

There have been cases in which resolution of chronic urticaria associated with thyrotoxicosis has also been seen in patients treated with antithyroid medication and in those treated with radioactive iodine.103 Subclinical hypothyroidism is an increasingly recognized entity and may underlie the thyroid-urticaria association in some cases.

Traditional Chinese Medicine/Acupuncture Therapy

Acupuncture has long been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) to effectively treat urticaria106,107 and type I allergic conditions.108 Known as “wind wheal,” urticaria is also referred to by Chinese practitioners as the “hidden rash,” owing to its ephemeral nature.

Three standard TCM etiologies are considered for urticaria. Urticarial disease due to wind heat typically manifests as red rashes with pruritus. Wind damp etiology correlates with lighter-colored rashes and a heavy sensation in the body. Alternatively, red rashes that appear with concomitant epigastric or abdominal pain and diarrhea or constipation are considered a derivation of stomach and small intestinal heat. Acute urticaria can be easily and effectively treated with acupuncture, in which LI11 (Quchi), Sp10 (Xuehai), Sp6 (Sanyinjiao), and S36 (Zusanli) are the acupuncture points most commonly prescribed.108 Auricular acupuncture may also accompany body acupuncture points for enhanced effect. External herbal washes with Fructus arctii (burdock) are also used in TCM.

Supplements

Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12 has been anecdotally reported to be of value in the treatment of acute and chronic urticaria.109,110 Although serum vitamin B12 levels are normal in most patients, additional vitamin B12 appears to be of value. However, because injectable vitamin B12 was used, the placebo effect (see Chapter 7) cannot be ruled out.

Quercetin

Considering the importance of mast cell degranulation in the pathogenesis of urticaria, quercetin’s significant in vitro activity as a mast cell stabilizer (and inhibitor of many of the pathways of inflammation; see Chapter 95) suggests that it may be very useful in treating urticaria. This possibility is strengthened by the observation that sodium cromoglycate (at 200 to 400 mg four times daily), a compound similar to quercetin, confers excellent protection against the development of urticaria and angioedema in response to ingested food allergens.111

Fish Oil

Three patients with salicylate-induced urticaria experienced alleviation of symptoms following dietary supplementation with omega-3 fatty acids. All three patients experienced severe urticaria, asthma requiring systemic steroid therapy, and anaphylactic reactions. After dietary supplementation with 10 g daily of fish oil providing 3000 mg EPA+DHA for 6 to 8 weeks, all three experienced complete or virtually complete resolution of symptoms, allowing discontinuation of systemic corticosteroid therapy. Symptoms relapsed after dose reduction.112

Diagnosis

Diagnosis

Physical Evaluation and History

A thorough history and physical evaluation are imperative for the proper diagnosis of urticaria and should include a careful history listing all medications, supplements, and botanicals. Evaluation should also detail travel, recent infection, occupational exposure, timing and onset of lesions, morphology, associated symptoms, family medical history, and pre-existing allergies. Contact sensitivities such as latex allergy113 and exposure to physical stimuli should be documented. History of tattoos should be explored for possible correlations. A diet and lifestyle diary that chronicles date and time, foods eaten, major activities, bowel and urine habits, and stress should be gathered in order to fully to characterize the potential temporal relationships of urticaria with specific ingested foods and activities. A comprehensive physical examination can also uncover important diagnostic clues that may help to diagnose comorbidities.

Laboratory Testing

The appropriate role of laboratory testing and studies in chronic urticaria remains controversial.10 One review of 29 large studies of laboratory testing in chronic urticaria, involving 6462 patients, demonstrated no relationship between numbers of identified diagnoses and numbers of performed tests.114 This review noted that systemic diseases (which excluded physical urticarias, allergens, infections, and psychological causes) were identified and believed to be related causally to the urticaria only in 1.6% of patients; these diseases included vasculitis, thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, other rheumatic disease, hereditary angioedema, and hematologic or oncologic conditions.

The use of screening skin testing for food allergies is also controversial.10,59 It is known that many patients with food-induced urticaria have diagnosed themselves without the help of a specialist. Skin testing for foods in the patient with chronic urticaria is fraught with false-positive and false-negative results. In the absence of a specific history suggestive of a particular food allergy (history of exposure and time course of subsequent symptoms consistent with typical food allergy), such skin testing can be counterproductive, particularly in patients with dermatographism and “twitchy” mast cells.10

Although not recommended for most cases of chronic urticaria, some medical literature suggests that a skin biopsy specimen can provide useful information to rule out urticarial vasculitis when this condition is suspected clinically.10 Research laboratories can also focus on autoimmune urticaria and detect the presence of anti-FcεRIα autoantibodies, but these tests are neither standardized nor routinely or widely available. Some urticaria specialists assess for such autoantibodies clinically and indirectly through autologous serum skin testing, whereby the patient’s serum is centrifuged and used for skin-prick testing in this form of a semiquantitative functional assay for autoimmunity to IgE or IgE receptors bound to cutaneous mast cells. This test is about 75% sensitive and 74% specific for the presence of the autoantibodies.10

Therapeutic Approach

Therapeutic Approach

Regarding conventional management of chronic urticaria, patients often show incomplete responses to antihistamines and are often uncomfortable and frustrated by chronic pruritus. Some cases do respond to systemic corticosteroids, but the potentially serious side effects associated with these medications preclude their safe chronic use.10 The wide variety of drugs used singly or in combination for this condition is a testament to conventional medicine’s inability to fully address and treat the symptoms as well as the underlying causes of urticaria; see Box 211-3 for a complete list of conventional drugs used to treat urticaria.

BOX 211-3 Drugs Used to Treat Urticaria

Second-generation histamine1 (H1) receptor antagonists:

First-generation H1 receptor antagonists:

H1 and histamine2 (H2) receptor antagonists:

• Doxepin (Sinequan)—sedation, increased appetite, resultant weight gain

• Cimetidine (Tagamet)—interference with hepatic microsomal enzymes and androgen receptors

Data from references 1 and 8.

Diet

Although rarely used in conventional medical therapy, even the standard medical literature is beginning to recognize the wisdom of the elimination diet.10 An elimination or oligoantigenic diet is of utmost importance in the treatment of chronic urticaria (see Chapters 19 and 54). The diet should eliminate not only suspected allergens but also all food additives.

The strictest elimination diets allow only water, lamb, rice, pears, and vegetables. Those foods most commonly associated with inducing urticaria (i.e., milk, eggs, chicken, fruits, nuts, and additives) should definitely be avoided.66 Foods containing vasoactive amines should be eliminated even if no direct allergy to them is noted. The primary foods to eliminate are cured meat, alcoholic beverages, cheese, chocolate, citrus fruits, and shellfish.

Psychological

The patient should perform relaxation techniques daily. Listening to audio relaxation programs may be an appropriate way to induce the desired state. Appropriate “mind-body” management programs leading to good clinical outcomes for chronic urticaria is dependent on the clinician’s ability to discern unique patient “stories.”

1. Muller B.A. Urticaria and angioedema: a practical approach. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1123–1128.

2. Czarnetzki B.M. Urticaria. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986.

3. Mathews K.P. A current view of urticaria. Med Clin North Am. 1974;58:185–205.

4. Dreskin S. Urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004:24. XI

5. Grattan C.E. Autoimmune urticaria. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:163–181.

6. Keahey T.M. The pathogenesis of urticaria. Dermatol Clin. 1985;3:13–28.

7. Shakouri A., Compalati E., Lang D.M., Khan D.A. Effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori eradication in chronic urticaria: evidence-based analysis using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation system. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010 Aug;10(4):362–369.

8. Wedi B., Raap U., Wieczorek D., Kapp A. Urticaria and infections. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2009 Dec 1;5(1):10.

9. Alangari A.A., Twarog F.J., Shih M.C., et al. Clinical features and anaphylaxis in children with cold urticaria. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e313–e317.

10. Dibbern D.A., Jr., Dreskin S. Urticaria and angioedema: an overview. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:141.

11. Katz J.P., Lichtenstein G.R. Rheumatologic manifestations of gastrointestinal diseases. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1998;27:533–562.

12. Parke A.L. Gastrointestinal disorders and rheumatic diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1991;3:160–165.

13. Zanjanian M.H. The intestine in allergic diseases. Ann Allergy. 1976;37:208–218.

14. Yacyshyn B., Meddings J., Sadowski D., et al. Multiple sclerosis patients have peripheral blood CD45RO? B cells and increased intestinal permeability. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:2493–2498.

15. Guida B., De Martino C.D., De Martino S.D., et al. Histamine plasma levels and elimination diet in chronic idiopathic urticaria. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2000;54:155–158.

16. Andrews G.C. Andrews’ diseases of the skin, ed 7. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1982. 131

17. Winkelmann R.K. Food sensitivity and urticaria or vasculitis. In: Brostoff J., Challacombe S.J. Food allergy and intolerance. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1987:602–617.

18. Ormerod A.D., Reid T.M., Main R.A. Penicillin in milk: its importance in urticaria. Clin Allergy. 1987;17:229–234.

19. Wicher K., Reisman R.E. Anaphylactic reaction to penicillin in a soft drink. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980;66:155–157.

20. Schwartz H.J., Sher T.H. Anaphylaxis to penicillin in a frozen dinner. Ann Allergy. 1984;52:342–343.

21. Boonk W.J., Van Ketel W.G. The role of penicillin in the pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1982;106:183–190.

22. Lindemayr H., Knobler R., Kraft D., et al. Challenge of penicillin allergic volunteers with penicillin contaminated meat. Allergy. 1981;36:471–478.

23. Settipane R.A., Constatine H.P., Settipane G.A. Aspirin intolerance and recurrent urticaria in normal adults and children. Allergy. 1980;35:149–154.

24. Warin R.P. The effect of aspirin in chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1960;72:350–351.

25. Moore-Robinson M., Warin R.P. Effects of salicylates in urticaria. Br Med J. 1967;4:262–264.

26. Champion R.H., Roberts S.O., Carpenter R.G., et al. Urticaria and angio-oedema: a review of 554 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1969;81:588–597.

27. James J., Warin R.P. Chronic urticaria: the effect of aspirin. Br J Dermatol. 1970;82:204–205.

28. Samter M., Beers R.F., Jr. Concerning the nature of intolerance to aspirin. J Allergy. 1967;40:281–291.

29. Michaelsson G., Juhlin L. Urticaria induced by preservatives and dye additives to food and drugs. Br J Derm. 1973;88:525–534.

30. Thune P., Granholt A. Provocation tests with antiphlogistica and food additives in recurrent urticaria. Dermatologica. 1975;151:360–372.

31. Doeglas H.M. Reactions to aspirin and food additives in patients with chronic urticaria, including the physical urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:135–144.

32. Warin R.P., Smith R.J. Challenge test battery in chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:401–410.

33. Settipane G.A., Chafee F.H., Postman I.M., et al. Significance of tartrazine sensitivity in chronic urticaria of unknown etiology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1976;57:541–549.

34. Kaaber K. Colouring and preservative agents and chronic urticaria. Value of a provocative trial and elimination diet. Ugeskr Laeger. 1978;140:1473–1476.

35. Fujita M., Yakimoto T., Aoki T., et al. Provocation tests with aspirin and sodium benzoate in urticaria. Japan J Derm. 1978;88:709–713.

36. Neuman I., Elian R., Nahum H., et al. The danger of “yellow dyes” (tartrazine) to allergic subjects. Clin Allergy. 1978;8:65–68.

37. August P.J. Successful treatment of urticaria due to food additive with sodium cromoglycate and an exclusion diet. In: Pepys J., Edward A.M. The mast cell: its role in health and disease. Tunbridge Wells, UK: Pitman Medical, 1979.

38. Meynadier J., Guilhou J., Meynadier J., et al. Chronic urticaria. Etiologic and therapeutic evaluation of 150 cases. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1979;106:153–158.

39. Lindemayr H., Schmidt J. Intolerance to acetylsalicylic acid and food additives in patients suffering from chronic urticaria. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1979;91:817–822.

40. Mikkelsen H., Larsen J.C., Tarding F. Hypersensitivity reactions to food colours with special reference to the natural colour annatto extract (butter colour). Arch Toxicol Suppl. 1978;1:141–143.

41. Wutrich B., Hacki-Herrmann D. Zur atiologie der urticaria. Eine retropektive studie anhand von 316 konsekutiven fallen. Z Hautkr. 1980;55:102–111.

42. Gibson A., Clancy R. Management of chronic idiopathic urticaria by the identification and exclusion of dietary factors. Clin Allergy. 1980;10:699–704.

43. Juhlin L. Recurrent urticaria. Clinical investigation of 330 patients. Br J Dermatol. 1981;104:369–381.

44. Wutrich B., Fabro L. Acetylsalicylsaure unc lebensmittel-additiva-intleranz bei urticaria, asthma bronchiale and chronischer rhinopathie. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1981;111:1445–1450.

45. Kirchhof B., Haustein U.F., Rytter M. Acetylsalicylic acid: additive intolerance phenomenon in chronic recurring urticaria. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1982;168:513–519.

46. Egyedi K., Torok L. Nachweis einer intoleranz von lebensmittel-additvstoffen durch proben mit salizylaten bei chronischer urticaria. Allergologie. 1982;5:234–235.

47. Merk Goerz G. Analgetika-intoleranz. Z Hautkr. 1983;58:535–554.

48. Hannuksela M. Food allergy and skin diseases. Ann Allergy. 1983;51:269–271.

49. Ortolani C., Pastorello E., Luraghi M.T., et al. Diagnosis of intolerance to food additives. Ann Allergy. 1984;53:587–591.

50. Simon R.A. Adverse reactions to drug additives. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1984;74:623–630.

51. Genton C., Frei P.C., Pecoud A. Value of oral provocation tests to aspirin and food additives in the routine investigation of asthma and chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1985;76:40–45.

52. Pigatto P.D., Riva F., Cattaneo A., et al. Chronic urticaria: clinico-therapeutic study on 300 cases. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1985;120:113–117.

53. Kemp A.S., Schembri G. An elimination diet for chronic urticaria of childhood. Med J Aust. 1985;143:234–235.

54. Ziegler B., Haustein U.F. Intolerance reactions to non-steroidal antiphlogistics and analgesics in chronic recurrent urticaria. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1986;172:313–317.

55. Supramaniam G., Warner J.O. Artificial food additive intolerance in patients with angio-oedema and urticaria. Lancet. 1986;2:907–909.

56. Perry C.A., Dwyer J., Gelfand J.A., et al. Health effects of salicylates in foods and drugs. Nutr Rev. 1996;54:225–240.

57. Grattan C.E. Aspirin sensitivity and urticaria. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2003;28:123–127.

58. Bjarnason I., Williams P., Smethurst P., et al. Effect of non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs and prostaglandins on the permeability of the human small intestine. Gut. 1986;27:1292–1297.

59. Asad S.I., Youlten L.J., Lessof M.H. Specific desensitization in aspirin sensitive urticaria; plasma prostaglandin levels and clinical manifestations. Clin Allergy. 1983;13:459–466.

60. Kowalski M.L., Grzelewski-Ryzmowski I., Roznieki J., et al. Aspirin tolerance induced in aspirin-sensitive asthmatics. Allergy. 1984;39:171–178.

61. Mattila L., Kilpeläinen M., Terho E.O., et al. Food hypersensitivity among Finnish university students: association with atopic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2003;33:600–606.

62. Atkins F.M. The basis of immediate hypersensitivity reactions to foods. Nutrition Rev. 1983;41:229–234.

63. Wraith D.G., Merrett J., Roth A., et al. Recognition of food-allergic patients and their allergens by the RAST technique and clinical investigation. Clin Allergy. 1975;9:25–36.

64. Golbert T.M., Patterson R., Pruzansky J.J. Systemic allergic reactions to ingested antigens. J Allergy. 1969;44:96–107.

65. Galant S.P., Bullock J., Frick O.L. An immunological approach to the diagnosis of food sensitivity. Clin Allergy. 1973;3:363–372.

66. Pachor M.L., Andri L., Nicolis F., et al. Elimination diet and challenge test in diagnosis of food intolerance. Italian J Med. 1986;2:1–6.

67. Treudler R., Tebbe B., Steinhoff M., et al. Familial aquagenic urticaria associated with familial lactose intolerance. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:611–613.

68. Zuberbier T., Pfrommer C., Specht K., et al. Aromatic components of food as novel eliciting factors of pseudoallergic reactions in chronic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:343–348.

69. Henz B.M., Zuberbier T. Most chronic urticaria is food-dependent, and not idiopathic. Exp Dermatol. 1998;7:139–142.

70. Rawls W.B., Ancona V.C. Chronic urticaria associated with hypochlorhydria or achlorhydria. Rev Gastroenterol. 1951;18:267–271.

71. Baird P.C. Etiology and treatment of urticaria: diagnosis, prevention and treatment of poison-ivy dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 1941;224:649–658.

72. Allison J.R. The relation of hydrochloric acid and vitamin B complex deficiency in certain skin diseases. South Med J. 1945;38:235–241.

73. Gloor M., Heinkel K., Schulz U. Pathogenetic significance of gastric functional disorders in allergic, chronic urticaria. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1972;158:96–102.

74. Husz S., Berko G., Szabo R., et al. Immunoelectrophoresis in the dermatologic practice. III. Dysproteinemias (chronic urticaria, drug allergy). Dermatol Monatsschr. 1974;160:93–100.

75. Zuberbier T., Chantraine-Hess S., Hartmann K., et al. Pseudoallergen-free diet in the treatment of chronic urticaria: a prospective study. Acta Derm Venereol (Stockh). 1995;75:484–487.

76. Lockey S.D. Allergic reactions to F D and C Yellow No. 5, tartrazine, an aniline dye used as a coloring and identifying agent in various steroids. Ann Allergy. 1959;17:719–721.

77. Collins-Williams C. Clinical spectrum of adverse reactions to tartrazine. J Asthma. 1985;22:139–143.

78. Lessof M.H. Reactions to food additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 1995;25(Suppl 1):27–28.

79. Warrington R.J., Sauder P.J., McPhillips S. Cell-mediated immune responses to artificial food additives in chronic urticaria. Clin Allergy. 1986;16:527–533.

80. Natbony S.F., Phillips M.E., Elias J.M., et al. Histologic studies of chronic idiopathic urticaria. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;71:177–183.

81. Juhlin L. Additives and chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1987;59:119–123.

82. Swain A.R., Dutton S.P., Truswell A.S. Salicylates in foods. J Am Diet Assoc. 1985;85:950–960.

83. Kulczycki A. Aspartame-induced urticaria. Ann Intern Med. 1986;104:207–208.

84. Moneret-Vautrin D.A., Faure G., Bene M.C. Chewing-gum preservative induced toxidermic vasculitis. Allergy. 1986;41:546–548.

85. Yang W.H., Purchase E.C. Adverse reactions to sulfites. CMAJ. 1985;133:865–880.

86. Vally H., Misso N.L., Madan V. Clinical effects of sulphite additives. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009 Nov;39(11):1643–1651.

87. Birkmayer J.G.D., Beyer W. Biological and clinical relevance of trace elements. Artzl Lab. 1990;36:284–287.

88. Vaida G.A., Goldman M.A., Bloch K.J. Testing for hepatitis B virus in patients with chronic urticaria and angioedema. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1983;72:193–198.

89. Schade C., Kaben U., Westphal H.J. Occurrence of yeasts and therapeutic results in chronic urticaria. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1975;161:187–195.

90. Holti G. Management of pruritus and urticaria. Br Med J. 1967:155–158. I

91. Serrano H. Hypersensitivity to “candida albicans” and other fungi in patients with chronic urticaria. Allergol Immunopathol. 1975;3:289–298.

92. James J., Warin R.P. An assessment of the role of Candida albicans and food yeast in chronic urticaria. Br J Dermatol. 1971;84:227–237.

93. Rives H., Pellerat J., Thivolet J. Chronic urticaria and Quincke’s oedema. 100 case reports: allergology and therapeutic results. Dermatologica. 1972;144:193–204.

94. Vivarelli I., Mancosu A. Data on 2 therapeutic trends in the treatment of urticaria: desensitization to Candida. Use of vitamin K. Minerva Dermatol. 1967;42:441–442.

95. Westphal H.J., Schade C., Kaben U. Specific desensitization in patients with chronic urticaria due to yeasts and intestinal colonization of yeasts. Dermatol Monatsschr. 1976;162:912–915.

96. Green G., Koelsche G., Kierland R. Etiology and pathogenesis of chronic urticaria. Ann Allergy. 1965;23:30–36.

97. Shertzer C.L., Lookingbill D.P. Effects of relaxation therapy and hypnotizability in chronic urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:913–916.

98. Hannuksela M., Kokkonen E.L. Ultraviolet light therapy in chronic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1985;65:449–450.

99. Olafsson J.H., Larko O., Roupe G., et al. Treatment of chronic urticaria with PUVA or UVA plus placebo: a double-blind study. Arch Derm Res. 1986;278:228–231.

100. Chapman E.W., Maloof F. Bizarre clinical manifestations of hyperthyroidism. N Engl J Med. 1956;254:1–5.

101. Caravati C.M., Jr., Richardson D.R., Wood B.T., et al. Cutaneous manifestations of hyperthyroidism. South Med J. 1969;62:1127–1130.

102. Isaacs N.J., Ertel N.H. Urticaria and pruritus: uncommon manifestations of hyperthyroidism. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1971;48:73–81.

103. Rumbyrt J.S., Schocket A.L. Chronic urticaria and thyroid disease. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2004;24:215.

104. Leznoff A., Sussman G.L. Syndrome of idiopathic chronic urticaria and angioedema with thyroid autoimmunity: a study of 90 patients. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;84:66–71.

105. Cusack C., Gorman D.J. Role of thyroxine in chronic urticaria and angio-oedema. J R Soc Med. 2004;97:257.

106. Chen C.J., Yu H.S. Acupuncture treatment of urticaria. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:1397–1399.

107. Chen C.J., Yu H.S. Acupuncture, electrostimulation, and reflex therapy in dermatology. Dermatol Ther. 2003;16:87–92.

108. Lai X. Observation on the curative effect of acupuncture on type I allergic diseases. J Tradit Chin Med. 1993;13:243–248.

109. Simon S.W. Vitamin B12 therapy in allergy and chronic dermatoses. J Allergy. 1951;22:183–185.

110. Simon S.W., Edmonds P. Cyanocobalamin (B12): Comparison of aqueous and repository preparations in urticaria: possible mode of action. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1964;12:79–85.

111. Canonica G.W., Ciprandi G., Bagnasco M., et al. Oral cromolyn in food allergy: in vivo and in vitro effects. Clin Immunol Immunopathol. 1986;41:154–158.

112. Healy E., Newell L., Howarth P., et al. Control of salicylate intolerance with fish oils. Br J Dermatol. 2008 Dec;159(6):1368–1369.

113. Valks R., Conde-Salazar L., Cuevas M. Allergic contact urticaria from natural rubber latex in healthcare and non-healthcare workers. Contact Dermatitis. 2004;50:222–224.

114. Kozel M.M., Bossuyt P.M., Mekkes J.R., et al. Laboratory tests and identified diagnoses in patients with physical and chronic urticaria and angioedema: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:409–416.

115. Ros A.M., Juhlin L., Michaelsson G. A follow-up study of patients with recurrent urticaria and hypersensitivity to aspirin, benzoates and azo dyes. Br J Dermatol. 1976;95:19–24.

116. Doeglas H.M. Dietary treatment of patients with chronic urticaria and intolerance to aspirin and food additives. Dermatologica. 1977;154:308–310.

117. Valverde E., Vich J.M., Garcia-Calderon J.V., et al. In vitro stimulation of lymphocytes in patients with chronic urticaria induced by additives and food. Clin Allergy. 1980;10:691–698.

118. Verschave A., Stevens E., Degreef H. Pseudo-allergen free diet in chronic urticaria. Dermatologica. 1983;167:256–259.