16 Urology

Urological symptoms

Haematuria

Haematuria is often a sign of malignancy in the urinary tract and requires thorough investigation. Painful haematuria is commonly due to bladder infection; painless haematuria usually signifies cancer. Common causes of haematuria are shown in Box 16.1.

Investigations

• Urine examination by microscopy, culture, sensitivities, cytology

• Blood tests – urea, electrolytes, creatinine, calcium, alkaline phosphatase (ALP), prostate specific antigen (PSA)

• Plain X-ray – shows abnormal calcification in the urinary tract (Fig. 16.1). 90% of stones are visible.

Urinary tract infections

Upper urinary tract – kidneys and ureters

Congenital abnormalities

The most commonly encountered anatomical abnormalities of the kidneys and ureters are listed in Box 16.3.

Adenocarcinoma

Aetiology and pathology

This tumour is commonest in men in late middle age and often causes paraneoplastic syndromes (Table 16.1). These cancers are usually well encapsulated and contain areas of haemorrhage and necrosis. Spread is by local infiltration and blood-borne metastases. The tumour may grow into the renal veins and vena cava.

Table 16.1 Paraneoplastic syndromes in renal cell adenocarcinoma

| Event | Cause |

|---|---|

| Raised ESR | Changes in plasma proteins |

| Anaemia | Depressed erythropoiesis and haemolysis |

| Polycythaemia | Erythropoietin secretion |

| Hypercalcaemia | Tumour secretion of parathormone-like substance |

| Raised alkaline phosphatase concentration | Secretion from the tumour |

| Pyrexia | Circulating pyrogens |

| Hypertension | Secretion of renin |

| Amyloid deposition | Unknown |

| Peripheral neuropathy and myopathy | Unknown |

Clinical features

The tumour may present with symptoms due to the tumour, due to metastases or due to symptoms resulting from secretion from malignant tissue (see Table 6.3, p. 108). Symptoms include:

Stone disease

Symptoms depend on the size and position of the stone, and whether there is associated urinary infection. The classic presentation is of ureteric colic (Fig. 5.7, p. 94) (also commonly called renal colic) due to the passage of a stone along a ureter. Severe colicky pain (said to be as bad as labour pain) is felt in the loin, radiating to the groin and into the scrotum or labia. Vomiting is common. The loin may be tender but physical signs may be absent. Urine dipstix is usually positive for blood. Evidence of infection (dysuria, constant loin pain between colicky exacerbations, fever, loin tenderness) should be taken very seriously since an obstructed infected kidney may be irreparably damaged in less than 24 hours if not decompressed.

The differential diagnosis is important (Box 16.4). In particular, in individuals over 50, especially those who have never previously had urinary stones, ruptured aortic aneurysm must be considered and excluded.

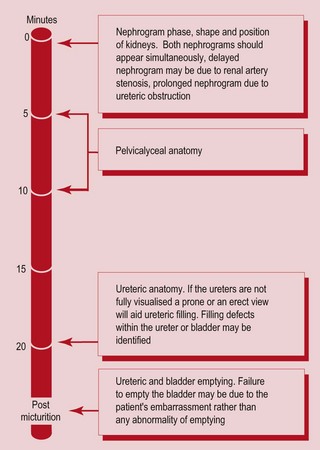

Diagnosis is by intravenous urogram (IVU). CT or ultrasound may also be used.

Most stones pass spontaneously, and analgesia is all that is required. Large (>0.5 mm) obstructing stones in the upper ureter are more likely to need treatment (Box 16.5).

Lower urinary tract

Bladder cancer

Investigations

• U&E (bladder tumours may obstruct the ureters and cause renal impairment)

• Cystoscopy (the definitive investigation, allows biopsy)

Advanced tumours invading bladder muscle require CT/MRI for local staging. The TNM classification is used, summarised in Table 16.2.

Table 16.2 Local staging of bladder cancer that is no longer superficial

| Stage | Findings |

|---|---|

| T2 | Superficial muscle is involved |

| T3A | Deep bladder muscle is involved |

| T3B | Extending beyond muscle but bladder still mobile |

| T4A | Adjacent structures involved |

| T4B | Fixed to pelvic wall |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastases |

Treatment

Superficial tumours require transurethral resection and intravesical chemotherapy, with regular flexible cystoscopic follow-up. More advanced cancers require cystectomy or radical radiotherapy. Prognosis is summarised in Table 16.3.

| Stage | Grade | 5-year survival (%) |

|---|---|---|

| pTiS | 75 | |

| pT1A | 1 | 95 |

| pT1B | 1 | 72 |

| pT1 | 3 | 39 |

| pT2 | 45 | |

| pT3 | 39 | |

| pT4 | 5 |

The prostate gland

Benign prostate hyperplasia (BPH)

Prostate cancer

Clinical features

A malignant prostate feels hard, knobbly and irregular on rectal examination.

Investigation

Bone scanning (Fig. 16.4) may show bone metastases and MRI scanning complements EUA to establish staging, which is by the TNM classification (Table 16.4).

| Stage | Findings |

|---|---|

| T1a | An incidental finding of tumour with low biological potential for aggressive behaviour in a prostate removed for clinically benign disease |

| T1b | An incidental finding of a tumour with potentially biological aggressive behaviour found in a prostate removed for clinically benign disease (high-grade or diffuse) |

| T1c | Tumour identified because of an elevated serum prostate-specific antigen |

| T2a | Tumour involving half a lobe or less |

| T2b | More than half a lobe but not both |

| T2c | Both lobes |

| T3 | Tumour extends through capsule and may involve seminal vesicle |

| T4 | Tumour fixed invasive of adjacent structures other than seminal vesicle |

Testes and scrotum

Undescended testes

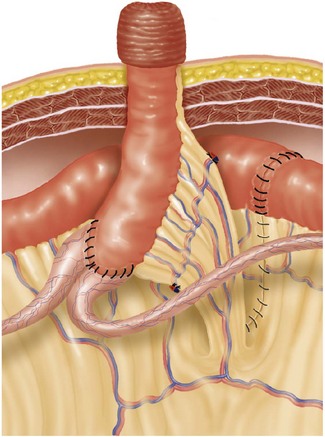

Undescended testes occur in 30% of premature infants and 3% of full term boys. By one year only 1% have failed to descend into the scrotum and spontaneous descent is rare after this age. The complications of undescended testes are listed in Box 16.6. Treatment is by orchidopexy between 1 and 2 years of age.

Testicular cancer

Testicular cancer accounts for only 1–2% of malignancy in males but is the commonest solid tumour in males aged 20–35. The cause is unknown, but maldescended testes have a much higher incidence of malignant change. Types of testicular tumours are summarised in Box 16.7. For clinical features see Table 16.5.

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

| Painless lump in scrotum | Hard lump in body of testis |

| History of trauma often described | Non-tender |

| 10% of patients had previous orchidopexy | 5% of tumours are bilateral |

| Pain/dragging sensation in scrotum | Gynaecomastia (with choriocarcinoma) |

| Symptoms due to metastases (e.g. backache, haemoptysis) |

Investigation

Tumour markers aid diagnosis and allow monitoring of effectiveness of treatment (Table 16.6). Ultrasound is helpful in defining the nature of the lesion. CT of the chest and abdomen is required for staging (Table 16.7).

| Tumour marker | Type of tumour |

|---|---|

| Alpha-fetoprotein and beta-HCG | Teratomas |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Teratomas and seminomas |

| Placental ALP | Seminomas |

Table 16.7 Staging of testicular tumours (Royal Marsden Hospital Staging System)

| Stage | Details |

|---|---|

| Testis | |

| I | Tumour confined to testis |

| IM | Rising concentrations of serum markers with no other evidence of metastasis |

| II | Abdominal node metastasis |

| A | ≤2 cm in diameter |

| B | 2–5 cm in diameter |

| C | >5 cm in diameter |

| III | Supradiaphragmatic nodal metastasis |

| ABC | Node stage as defined in stage II |

| M | Mediastinal |

| N | Supraclavicular, cervical or axillary |

| O | No abdominal node metastasis |

| IV | Extralymphatic metastasis |

| Lung | |

| L1 | ≤3 metastases |

| L2 | ≥3 metastases, all ≤2 cm in diameter |

| L3 | ≥3 metastases, one or more of which are ≥2 cm in diameter |

| H+, Br+, Bo+ | Liver, brain or bone metastases |

Scrotal swellings

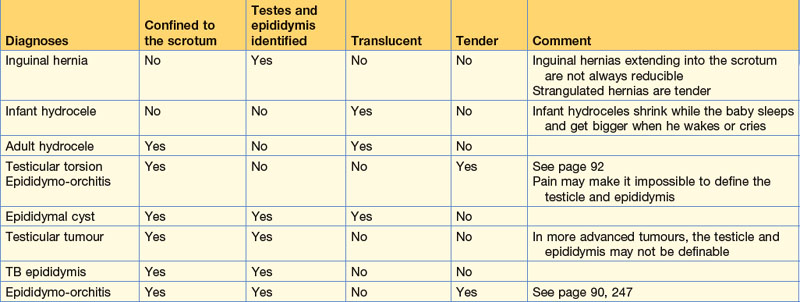

Scrotal swellings can be diagnosed by establishing four features.

• Is the swelling confined to the scrotum?

• Can the testes and epididymis be identified?

Establishing these properties allows most scrotal swellings to be diagnosed (Table 16.8). Scrotal ultrasound is useful to confirm the clinical diagnosis.