CHAPTER 16 Urology

Congenital disorders of the urinary tract

Kidney and ureter

Haematuria

Haematuria is the passage of red blood cells in the urine. This may vary from a few red cells detected on ‘stix’ testing to the passage of frank blood. Haematuria may be noted at the beginning of micturition, throughout micturition or at the end of micturition. Care must be taken to avoid menstrual bleeding being mistaken for haematuria. Other causes of red urine include excessive beetroot ingestion, rifampicin, porphyria, haemoglobinuria and myoglobinuria. (For causes of haematuria → Table 16.1.)

| Kidney | Glomerular disease |

| Polycystic kidneys | |

| Carcinoma | |

| Stone | |

| Trauma (including renal biopsy) | |

| Tuberculosis | |

| Embolism | |

| Renal vein thrombosis | |

| Vascular malformation | |

| Ureter | Stone |

| Neoplasm | |

| Bladder | Carcinoma |

| Stone | |

| Trauma | |

| Inflammatory – cystitis, tuberculosis, bilharzia | |

| Prostate | Benign prostatic hypertrophy |

| Neoplasm | |

| Urethra | Trauma |

| Stone | |

| Urethritis | |

| Neoplasm | |

| General | Anticoagulants |

| Thrombocytopenia | |

| Haemophilia | |

| Sickle cell disease | |

| Malaria |

Obstructive uropathy

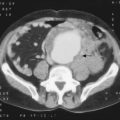

Hydronephrosis is the distension of the calyces and pelvis of the kidney owing to obstruction to the outflow of urine. It may be bilateral or unilateral. (For causes of hydronephrosis → Table 16.2.)

| Unilateral | Pelviureteric junction obstruction

Ureteric obstruction |

Investigations

Calculous disease

Types of calculi

Investigations

Emergency for severe renal pain or ureteric colic:

Following acute attack or routine for urinary symptoms or incidental finding of stone:

Treatment

Acute symptoms – ureteric colic:

Tumours of the renal tract

Bladder

Treatment of transitional cell carcinoma

Urinary tract infections (UTIs)

Urinary tract tuberculosis

Investigation

Prostate

Urinary retention

The retention of urine may be acute, chronic or acute-on-chronic. Patients with acute retention present as surgical emergencies. (For causes of urinary retention → Table 16.3.)

| Local | |

| Urethral lumen or bladder neck | Urethral valves |

| Tumours | |

| Stones | |

| Blood clot | |

| Meatal ulcer or stenosis | |

| Urethral or bladder wall | Urethral trauma |

| Urethral stricture | |

| Urethral tumour | |

| Outside the wall | Prostatic enlargement |

| Faecal impaction | |

| Pelvic tumour | |

| Pregnant uterus | |

| Phimosis | |

| General | |

| Postoperative | |

| Neurogenic | Spinal cord injuries |

| Spinal cord disease, e.g. tabes dorsalis, spinal tumour, multiple sclerosis, diabetic autonomic neuropathy | |

| Drugs | Anticholinergics, antidepressants, alcohol |

Testes and epididymis

Varicocele

These are varicosities of the pampiniform plexus. More common on the left side.

Penis

Conditions of the foreskin

Circumcision

| Religious |

| Phimosis |

| Paraphimosis |

| Recurrent balanoposthitis |

| Diagnosis of underlying penile tumours |

| Trauma and tumour of foreskin |