23 Urological surgery

Assessment

Examination

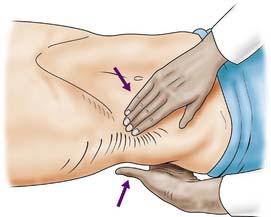

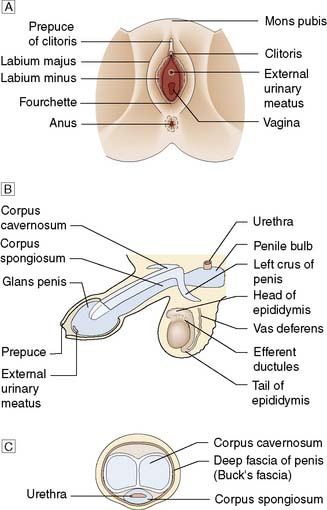

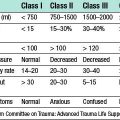

With the patient relaxed, the kidney can be balloted; lifted with one hand placed behind the loin and compressed by the other hand pressing downwards (Fig. 23.1). The ureter cannot be palpated. An enlarged bladder rises centrally out of the pelvis, is dull to percussion and may even be visible. In men, the hernial orifices, cords, testes and epididymes are examined with the patient standing and lying. If the foreskin is uncircumcised, it must be confirmed that it retracts and that the glans and meatus are normal. In women, the vulva, urethra and vagina must also be examined. A speculum examination should be carried out if there is any suspicion of vaginal or cervical abnormality. A full pelvic bimanual examination, whether in males or females, is best carried out under general anaesthesia with a muscle relaxant. A rectal examination is mandatory, not only to examine the prostate but also to detect abnormalities of the anal margin (haemorrhoids, fissures) and lower rectum (carcinoma).

Investigations

Intravenous urography (IVU)

A plain X-ray of the abdomen and pelvis is obtained to outline the areas of the kidneys, ureters and bladder (KUB film). The lumbar spine and pelvis, as well as stones in the region of the urinary tract, will be shown. An intravenous urogram (IVU) involves injecting iodine-containing contrast material intravenously and taking serial X-rays (Fig. 23.2) to demonstrate the renal pelvis and calyces, the rate of kidney emptying, the calibre of the ureters and the bladder outline. Once the bladder has filled, a ‘post-micturition’ film will demonstrate bladder emptying and the amount of residual urine.

Ultrasonography

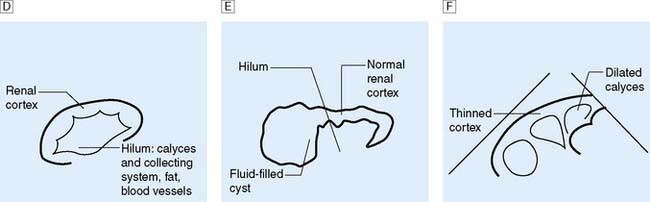

This is another means of first-line imaging (Fig. 23.3), tending to give superior information about the renal parenchyma but less about the collecting system. It also allows visualization of other related organs, such as the liver, spleen and gynaecological organs.

Special radiological investigations

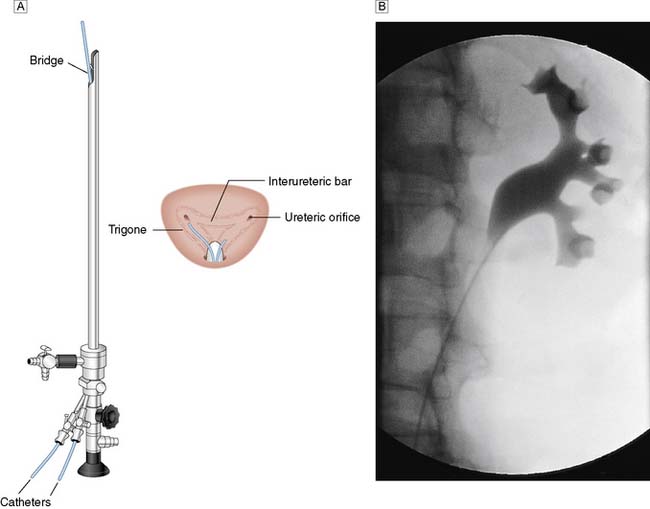

In certain circumstances a retrograde ureteropyelogram may be necessary. This involves retrograde injection of contrast material through a catheter placed in the lower ureter (Fig. 23.4). Abnormalities of the renal vessels can be demonstrated by renal angiography. Computed tomography (CT) is now the preferred method for imaging renal tumours. A micturating cystourethrogram (MCU) will outline the bladder, detect ureterovesical reflux and examine the bladder neck and urethra. The bladder is filled with contrast material (via a catheter) and emptying is then studied by X-ray screening. An ascending urethrogram, in which contrast medium is injected into the urethra, can be used to define strictures. When used in conjunction with a MCU, a descending urethrogram can also be obtained.

Nuclear imaging

Radio-labelled substances are used for two main purposes:

1. Detecting bony metastases from carcinoma of the prostate (bone scan). 99mTc-labelled methylene diphosphonate (MDP) is the most reliable method.

2. Measurement of renal function (scintigraphic renography). Occasionally ‘how a kidney looks’ does not correlate with ‘how it behaves’, e.g. hydronephrosis does not always mean the presence of obstruction. Renography allows assessment of obstruction to a kidney (e.g. from a pelviureteric obstruction), differential kidney function (i.e. how much each kidney is contributing to overall function), assess non-functioning areas of renal parenchyma (e.g. scarring) and allow accurate assessment of GFR. Radio-labelled mercaptuacetyltriglycine (MAG-3) has largely superseded technetium labeled diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (Tc-DTPA) for dynamic scanning. It is secreted from the renal tubules and is used in the identification of obstructed kidneys and to assess differential function. Dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA) is concentrated in the renal tubules and static imaging can be carried out some 2–3 hours after injection. Parenchymal defects such as scars, haematomas, lacerations or ischaemia may be demonstrated. Differential renal function can be quantified from measuring the DMSA concentration/density in each kidney.

Urodynamic studies

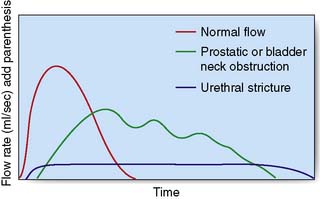

The maximum urinary flow rate during micturition can be measured using a flow meter when the voided volume is at least 150 ml or the values may be misleadingly low. The norm in males is 15–30 ml/s and in females 20–40 ml/s and a flow rate of less than 10 ml/s is abnormal. The flow rate pattern can help to determine the cause of obstruction (Fig. 23.5). Measurements of flow rate can be combined with cystometry to provide a measure of residual urine, bladder capacity, the capacity at which a desire to void occurs, and the detrusor pressures when the bladder is full and during maximum flow. Spontaneous detrusor contractions during bladder filling may indicate an unstable bladder, a cause of urgency and urge incontinence.

Upper urinary tract (kidney and ureter)

Anatomy

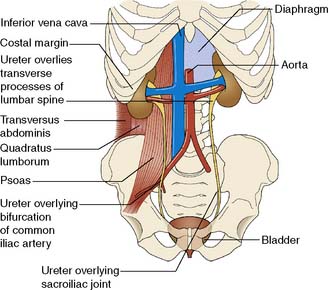

The two kidneys lie retroperitoneally on the posterior abdominal wall. Each is approximately 12 cm long, 6 cm wide and 3 cm thick. The upper pole of the kidney lies on the diaphragm, which separates it from the pleura and the 11th and 12th ribs. Below this, it lies on the psoas, quadratus lumborum and transversus abdominis muscles from medial to lateral (Fig. 23.6). Anteriorly, the right kidney is covered by the liver, the second part of the duodenum and the ascending colon. The spleen, stomach, tail of pancreas, left colon and small bowel overlie the left kidney. The renal hilum lies medially and transmits from front to back the renal vein, renal artery and renal pelvis. The ureter begins at the renal pelvis and runs for 25 cm to the bladder. The abdominal ureter lies on the medial edge of the psoas muscle, which separates it from the tips of the transverse processes. It then crosses the bifurcation of the common iliac artery, which separates it from the sacroiliac joint, to enter the pelvis. The pelvic ureter runs on the lateral pelvic wall to just in front of the ischial spine, when it then turns medially and forward to enter the bladder. In the male, it is crossed by the vas deferens. In the female, it lies close to the lateral fornix of the vagina and is crossed by the uterine vessels, where it is vulnerable to damage during hysterectomy. The section of ureter that lies within the bladder wall functions as a flap valve to prevent reflux. Stones tend to impact at the three points where the ureter narrows: namely, the pelviureteric junction, the pelvic brim and the ureteric orifice.

Renal adenocarcinoma

Investigations

The initial investigation is ultrasound, followed by a staging contrast CT of the abdomen and chest (Fig. 23.7).

Management

Summary Box 23.1 Renal carcinoma

• Renal adenocarcinoma is the most common malignant renal tumour and is twice as common in males

• The carcinoma arises in the renal tubules and spreads early to the renal pelvis, producing haematuria. Later spread involves the renal vein (with bloodstream dissemination), perinephric invasion and lymphatic spread

• The clinical presentation is very varied. The triad of pain, haematuria and a mass may be late features, and early systemic effects include fever, polycythaemia, disordered coagulation and pyrexia of unknown origin

• The key investigations are ultrasonography, chest X-ray and contrast CT

• Treatment consists of radical nephrectomy; the tumour is not radiosensitive. The natural history of renal carcinoma is very variable and excision of solitary metastases may be worthwhile.

Renal and ureteric calculi

Investigations

IVU or CT KUB provides all the necessary information on the position of the stone (Fig. 23.8). Routine hematological and biochemical tests are needed to assess renal function and to exclude metabolic causes. A urine sample is cultured to determine whether there is infection. If obstruction is acute, its relief is the prime clinical need; if it is chronic and has caused renal damage, the surgical approach depends on the function of the affected kidney. This is best determined by radioisotope methods (renography).

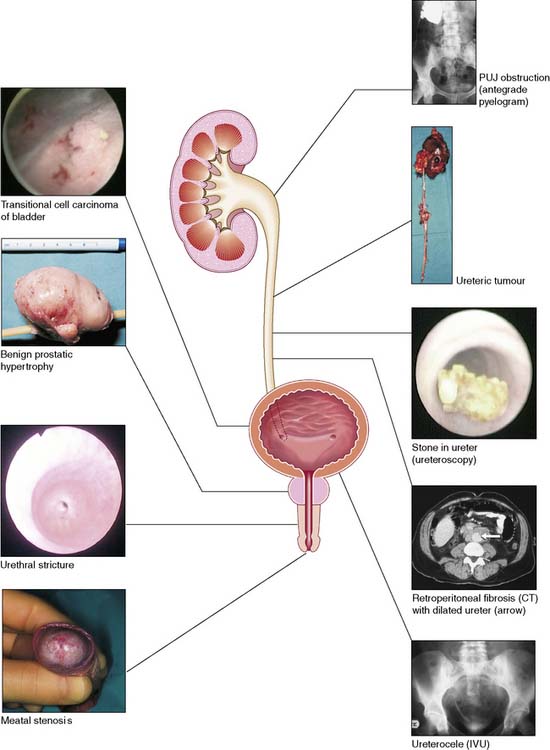

Upper tract obstruction

Obstruction may be due to extrinsic, intrinsic or intraluminal causes (Table 23.1). In the kidney, stones within the pelvicalyceal system and a congenital abnormality of the pelviureteric junction (see below) are the main causes of obstruction leading to hydronephrosis. More rarely, a sloughed renal papilla, blood clot or tumour may be the cause.

| Extrinsic |

Pelviureteric junction obstruction (idiopathic hydronephrosis)

Management

Either laparoscopic or open pyeloplasty is performed to remove the obstructing tissue and refashion the pelviureteric junction (PUJ) so that the lower part of the renal pelvis drains freely into the ureter (Fig. 23.9). It is not possible to predict the degree of recovery of renal function after the relief of obstruction, but a kidney contributing less than 10% of total renal function should be removed.

Retroperitoneal fibrosis

Pathology

• Idiopathic. The aetiology is unknown, although it may be associated with methysergide or analgesic abuse Mediastinal fibrosis and Dupuytren’s contracture may coexist

• Malignant infiltration. The fibrosis contains malignant cells that have metastasized from primary sites such as the breast, stomach, pancreas and colon

• Reactive fibrosis. Radiotherapy, resolving blood clot, or extravasation of sclerosants can lead to fibrotic change in the retroperitoneum.

Management

Summary Box 23.2 Urinary tract obstruction

Common causes of obstruction of the lower outflow tract

• Benign prostatic hyperplasia

• Bladder cancer involving the bladder neck

• Bladder-neck obstruction (dyssynergia, infection, neurological disorders)

• Urethral obstruction (congenital posterior urethral valves, blocked urinary catheter, trauma, infection, stricture).

Common causes of obstruction of the upper urinary tract

• Renal and ureteric calculi (80% are calcium oxalate/phosphate stones)

• Pelviureteric junction obstruction (idiopathic hydronephrosis)

• Retroperitoneal fibrosis (idiopathic/malignant infiltration/radiotherapy)

• Transitional cell carcinoma (with or without bleeding and clot)

• Congenital abnormalities (e.g. ectopic ureter, ureterocoele)

Lower urinary tract (bladder, prostate and urethra)

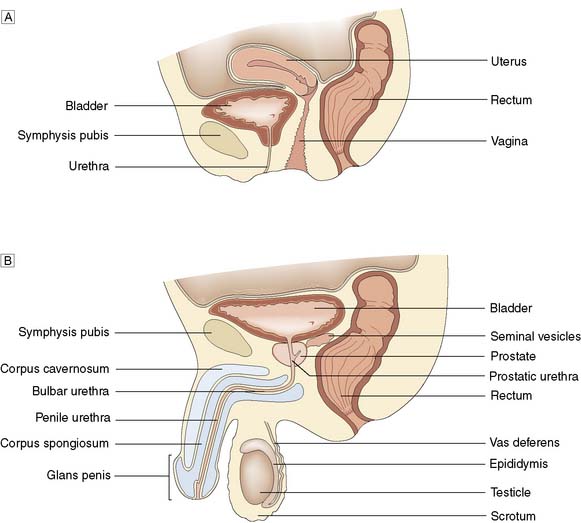

Anatomy

In the male, the prostate is pyramidal, with its base uppermost. It resembles the size and shape of a chestnut and surrounds the prostatic urethra. Traditionally described as having a median and two lateral lobes, it is better considered as being composed of a small central and a larger peripheral zone (Fig. 23.10).

Physiology

Trauma

Bladder

Closed injuries

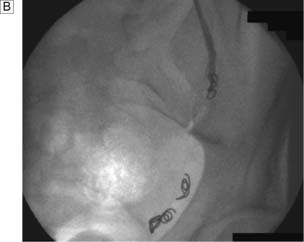

Intraperitoneal rupture typically occurs in a patient who has been drinking alcohol, has a full bladder and is assaulted and kicked in the abdomen. The dome of the bladder ruptures and urine extravasates into the peritoneum, causing intestinal ileus and abdominal distension. Extraperitoneal rupture is usually due to a major road traffic accident in which the pelvis has also been fractured when the bladder is not full, but may follow endoscopic resection of the prostate or a bladder tumour (Fig. 23.11).

Urethra

Open injuries

Penetrating injuries resulting in damage to the anterior or posterior urethra are rare.

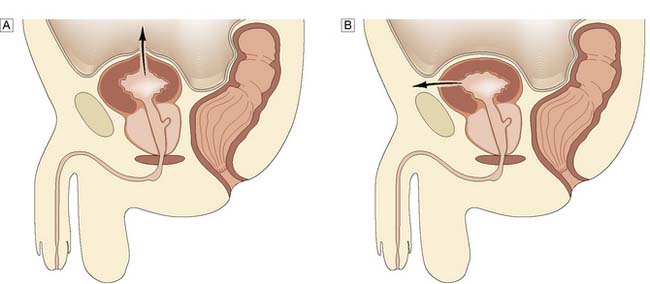

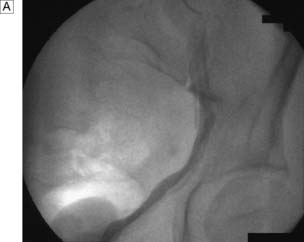

Investigations

If the physical signs suggest an anterior urethral injury, and the patient has passed clear urine, no further steps need be taken. If there is blood at the external meatus or the urine is blood-stained, a urethrogram using water-soluble contrast material may demonstrate the extravasation (Fig. 23.12). A catheter should never be passed in the emergency room. If urine is blood-stained, retrograde urethrography may be carried out but the radiological distinction between a rupture of the membranous urethra and an extraperitoneal bladder rupture may be difficult.

Bladder tumours

Staging

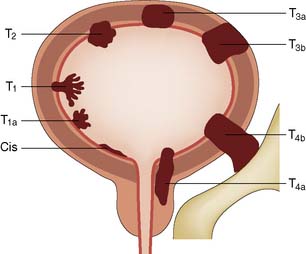

Biopsy is essential to confirm the diagnosis (cell type), determine the degree of cell differentiation (grade), and assess the depth to which the tumour has penetrated the bladder wall (stage). The TNM system of tumour classification is applicable to bladder tumours. Assessment of the primary tumour (T) is of prime clinical importance and requires bimanual examination under anaesthesia to judge the degree of penetration through the bladder wall. This is especially important for T2 and T3 tumours (Fig. 23.13). Clinical examination, urography and CT are used to assess the involvement of regional and juxtaregional lymph nodes (N). Assessment of distant metastases (M) requires clinical examination and CT. Histopathological examination guides the choice of treatment. Biopsy gives accurate information on superficial tumours, but depth of invasion of invasive tumours cannot be assessed precisely as the biopsy does not examine the full thickness of the bladder wall.

Clinical features

More than 80% of patients have haematuria, which is usually painless (Fig. 23.14). It should be assumed that such bleeding is from a tumour until proved otherwise. In women, symptoms of cystitis are so common that occasional bleeding may be thought to be part of an infective problem. Therefore, in cases of haematuria, MSSU is mandatory with further investigation required if no growth is found. In men, symptoms of bladder outflow obstruction are common and may include bleeding. Bleeding at initiation of micturition suggests a prostatic, or urethral, origin. Haematuria throughout micturition suggests either a bladder or upper tract cause. A tumour at the lower end of a ureter or a bladder tumour involving the ureteric orifice may cause obstructive symptoms. However, frank haematuria may be the only presenting symptom. Examination is usually unhelpful. Rectal examination detects only advanced tumours.

Investigations

Because upper tract tumours are much less common, they may be overlooked in the presence of an obvious bladder tumour. Both may occur together, and the whole of the urothelium must be examined on the IVU or CTU (Fig. 23.15). If there is any suspicious filling defect in the ureter, a retrograde ureteropyelogram is necessary. In cases of frank haematuria, investigations consist of flexible cystoscopy, peformed under local anaesthesia, and either an ultrasound of the kidneys with an IVU or a CTU. Where a lesion is found within the bladder, cystourethroscopy and examination under anaesthesia are performed (Fig. 23.16). With the patient relaxed under general anaesthesia, the bladder and tumour are examined bimanually to determine the depth of spread. The physical features of the tumour(s) are noted, the normal bladder mucosa is inspected and the tumour is fully resected if possible. If not, biopsies are taken from the tumour and any other suspicious areas.

Management

Superficial bladder tumours (Ta, T1)

Ideally these are treated by formal transurethral resection of the blabber tumour (TURBT) down to and including detrusor muscle; however, they can also be treated solely by endoscopic diathermy if required. Intravesical chemotherapy (mitomycin C) is useful to treat multiple low-grade bladder tumours and to reduce recurrence (EBM 23.1). Regular check cystoscopies are required. Recurrences are mostly treated by repeat diathermy or resection but, if they become very frequent and excessive, cystectomy may be advisable. Carcinoma in situ (Cis) may be present in mucosa that appears normal or in association with a proliferative tumour. Cis can also exist as a separate entity, when there may be only a generalized redness (malignant cystitis). Cis should be considered in patients with ongoing irritative urinary symptoms associated with pain or symptoms suggestive of ongoing urinary tract infection, both in the absence of urinary tract infection upon MSSU culture. Untreated patients with Cis have a high risk of progression to invasive cancer. Cis responds well to intravesical bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) treatment. However, if there is any doubt about the response, and especially if there is any pathological evidence of progression, more aggressive treatment is warranted.

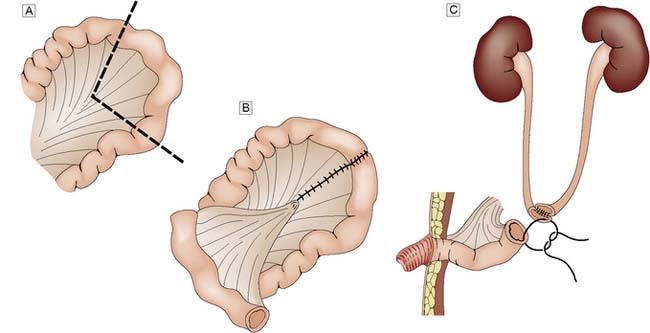

Invasive bladder tumour (T2–T3s)

Management is controversial. For patients under 70 years of age, radical cystectomy is recommended. In older patients, radiotherapy may be a better option. Unfortunately, this may not always cure the tumour and ‘salvage’ cystectomy may be needed. Cystectomy always necessitates urinary diversion. Where the urethra can be retained, it may be possible to construct a new bladder from colon or small bowel (orthotopic bladder replacement), so achieving continence. Alternatively, the urine is collected in an internal reservoir that is connected to the body surface via a continent conduit (ileum or appendix), through which the patient drains the urine at regular intervals with a catheter. In less favourable circumstances, an ileal conduit should be performed (Fig. 23.17). In some countries where an ‘ostomy’ is not acceptable, the ureters can be implanted into the sigmoid colon (ureterosigmoidostomy). However, renal infection and metabolic disturbances are potentially serious complications of this procedure. An invasive T4 tumour, fixed to the pelvis or surrounding organs, is inoperable and only palliative treatment can be given.

Carcinoma of the prostate

Pathology

Summary Box 23.3 Urothelial tumours

• The urothelium or transitional cell epithelial lining of the urinary tract extends from the renal papilla to the distal urethra

• The incidence of urothelial cancer is increasing, possibly because of increasing exposure to occupational carcinogens, smoking and analgesic abuse

• Almost all urothelial cancers are transitional cell tumours and the vast majority occur in the bladder. Squamous cancers are rarer and are associated with chronic irritation or inflammation (e.g. calculi and schistosomiasis). Adenocarcinomas are extremely rare

• Frank haematuria is present in 80% of cases

• Transitional cell cancers of the bladder are treated as follows:

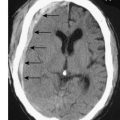

(Table 23.2). Metastatic spread to pelvic lymph nodes occurs early. One-third of clinically localized tumours at the time of presentation will have spread to regional nodes. Metastases to bone, mainly the lumbar spine and pelvis, occur in some 10–15% of cases.

| T (Tumour) | |

(TURP = transurethral resection of the prostate)

* Sobin LH, Wittekind C, eds. TNM classification of malignant tumours, 6th edn. Chichester: John Wiley; 2002.

Clinical features

The presentation of patients with prostatic carcinoma is similar to benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH); one-quarter present with acute retention (Fig. 23.18). Occasionally, the tumour extends posteriorly around the rectum and causes alteration in bowel habit. Presenting symptoms and signs due to metastases are much less common, but include back pain, weight loss, anaemia and renal failure secondary to ureteric obstruction. On rectal examination, the prostate feels nodular and stony hard but many irregular prostates, even those with nodules, are not malignant. Conversely, 50–60% of malignant prostates are not palpably abnormal on rectal examination.

Management

Prostatic cancer is sensitive to endocrine influences (EBM 23.2) as testoterone is a trigger for moving prostate cells through the cell cycle thereby stimulating mitosis. Management is best considered in three clinical groups, as follows.

Prognosis

Summary Box 23.4 Prostatic cancer

• In the UK this is the second most common cancer in men, presents at a mean age of 70, and is increasing in incidence

• The carcinoma may be incidental (i.e. found on histological examination), clinically apparent (bladder outflow obstruction and a hard craggy prostate) or occult (metastatic disease)

• Metastatic spread may occur early; one-third of clinically confined cancers have spread to lymph nodes, and 10–15% of all new cases have bony spread (to lumbar spine and pelvis)

• Treatment of prostatic cancer varies:

° Incidental or focal cancer. If well differentiated, then life expectancy can be normal with a watch-and-wait policy. If the cancer contains undifferentiated cells, then either radical surgery or radiotherapy is considered

° Localized cancer with no evidence of bony metastases. Treated by either radical surgery or radiotherapy, keeping endocrine therapy in reserve

° Metastatic cancer. Treated by androgen depletion (orchiectomy) or androgen suppression (gonadotrophin releasing hormone analogues)

° Tumours localized to the prostate and amenable to radical curative treatment have a 10-year survival rate of 60–75%.

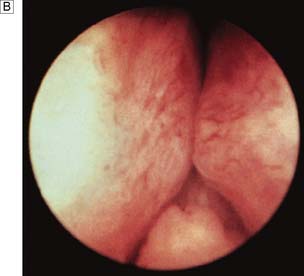

Benign prostatic hyperplasia

Pathology

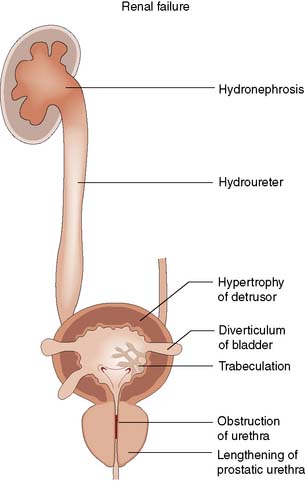

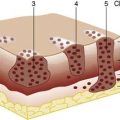

From about the age of 40 years, the prostate undergoes enlargement as the result of hyperplasia of periurethral tissue, which forms adenomas in the transitional zone of the prostate. Normal prostatic tissue is compressed to form a surrounding shell or capsule. There is considerable variation in the growth rates of the adenomas and in the proportions of stromal and epithelial tissue. A prostate that has been infected previously or has a preponderance of stromal tissue is firm and fibrous on rectal examination. Adenomas with an epithelial preponderance can grow to form large discrete masses weighing more than 100 g, and have a characteristic rubbery consistency, referred to as benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). Enlarging adenomas lengthen and obstruct the prostatic urethra, causing outflow obstruction and detrusor muscle hypertrophy. The muscle bands of the bladder form trabeculae, between which saccules form diverticula (Fig. 23.19). Occasionally, a diverticulum may become quite large, even larger than the bladder. Bladder diverticula empty poorly and are liable to the three main complications of urinary stasis: infection, stones and tumour. With progressive inability to empty the bladder completely (chronic retention), the risk of urinary infection and stone formation increases. Eventually, the residual urine volume may exceed one litre, resulting in progressive obstruction and dilatation of the ureters (hydroureter) and pelvicalyceal system (hydronephrosis). This ultimately leads to obstructive renal failure.

Investigations

A good history and examination are paramount. Further mandatory assessment includes blood for renal function, haemoglobin and electrolytes, urine culture and PSA. Prostatic cancer can occur with normal PSA values (0–4 ng/ml) while BPH can cause elevated values, so careful interpretation is required (Table 23.3). If digital rectal examination raises suspicion, needle biopsy is indicated. Ultrasound can detect bladder diverticula, intravesical stones and measure residual urine volume. A urine flow rate will quantify a reduction in urinary stream. A symptom score sheet will quantify the degree of inconvenience and bother. In some patients, especially the elderly, neurological or pharmacological causes for the changes in micturition must be considered. A pressure-flow urodynamic assessment may be necessary.

Table 23.3 Factors affecting the level of prostate-specific antigen (PSA)

| Causes of increase in PSA |

Management

Acute retention

This condition usually requires emergency admission to hospital. If there is a history of bladder outflow obstruction, conservative measures aimed at encouraging micturition (sedation, a warm bath) only delay the inevitable requirement for catheterization. A self-retaining Foley catheter (size 16 Fr) is passed using strict asepsis and connected to a closed drainage system. If it is not possible to pass a urethral catheter, the bladder is entered directly by puncture with a trocar/cannula (suprapubic cystostomy). A specimen of urine is cultured and, if there is microbiological evidence of an infection, antibiotics are given. If the history of urinary symptoms is short, the catheter can be removed after 12 hours (trial without catheter), following which normal voiding may occur. This is more likely if the patient is given α-blockers (EBM 23.3). If retention recurs, then definitive treatment with TURP is performed.

Urethral obstruction

Pathology

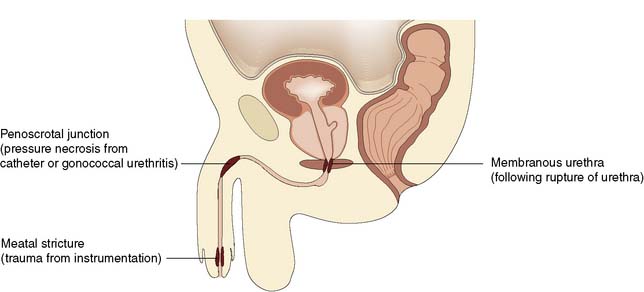

Obstruction of the urethra may be congenital, or due to a stricture or malignancy (Fig. 23.20). Foreign bodies, including urinary stones, may also be responsible. The complications include infection with periurethral abscess, fistulation and stone formation. Congenital valves in the posterior urethra occur only in boys. They lie at the level of the verumontanum and may cause gross obstructive changes in the bladder and upper urinary tracts at birth. Increasingly, this diagnosis is being established during pregnancy by ultrasound examination. If the diagnosis is established after birth, it is confirmed by micturating cystourethrography. Treatment consists of endoscopic incision of the valves. Urethral diverticulum is a rare cause of obstruction. More commonly, it is secondary to obstruction and infection in women. Urethral trauma or infection may result in a stricture, the severity of which is related to both the site and the extent of the insult. A posterior urethral stricture following major trauma may be surrounded by dense fibrous tissue, whereas healthy tissues may surround a stricture of the bulb of the urethra. The former requires major reconstructive surgery but urethral dilatation or incision can readily manage the latter. Rough inexpert use of any instrument (including a catheter) in the urethra can cause stricture formation. The principal organism responsible for inflammatory scarring and stricture of the urethra is Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Long-term use of a self-retaining catheter, although not necessarily associated with infection, can also cause an inflammatory reaction in the urethra.

Investigations

Urinary flow rate will help differentiate urethral strictures from bladder neck and prostatic obstruction, the former giving a uniformly low and prolonged (box-like) pattern (see Fig. 23.5). Post-micturition ultrasound may exclude an increased residual volume. An ascending and descending urethrogram will adequately demonstrate the urethral anatomy. The final investigation to assess a urethral lesion is cystourethroscopy.

Disorders of micturition – incontinence

Structural disorders

Structural causes of incontinence in males

Neurogenic disorders

Principles of management

Neuropathic patients

Summary Box 23.5 Micturition

• Micturition requires parasympathetic innervation (S2–S4) of the detrusor, sympathetic innervation (T10–L2) of the bladder neck and proximal urethra, and somatic innervation (S2–S4) of the bladder, pelvic floor and urethra

• Structural causes of disordered micturition in the male include prostatic enlargement, prostatectomy (dribble, stress and urge incontinence) and chronic illness/debility

• Structural causes of disordered micturition in the female include childbirth, surgery, radiotherapy and cystitis (infection, chronic interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome)

• Neurogenic causes of disordered micturition are:

° spinal cord damage (at/below T12–L1 – flaccid bladder with overflow; above T12–L1 – overactive bladder with incoordination of urinary sphincter, which results in poor bladder emptying)

° pelvic nerve damage (surgery, diabetic autonomic neuropathy)

External genitalia

Anatomy

In the male, these comprise the penis, testicles and scrotum; in the female, the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora and the clitoris (Fig. 23.21).

Carcinoma of the penis

This uncommon tumour has a prevalence of 1.5 cases per 100 000 and is generally attributed to poor hygiene associated with a non-retractile foreskin (Fig. 23.22). It is very rare in circumcised men and almost always occurs in the elderly. The cancer may be a papillary or an ulcerating squamous cell carcinoma. Local spread occurs early and the tumour may ulcerate and fungate. Lymphatic spread to inguinal lymph nodes is common; associated infection may also lead to lymphadenopathy. The patient may present with a purulent or blood-stained discharge. Unfortunately, many patients do not seek help until the lesion is advanced – some only when much of the penis is already destroyed and the inguinal lymph nodes are involved. The diagnosis must be confirmed by biopsy. Circumcision may cure early tumours confined to the prepuce. Early tumours confined to the glans may be treated by excision of the glans and skin grafting. Advanced tumours will require partial or total penile amputation, and often bilateral block dissection of the inguinal lymph nodes. Inoperable tumours are treated by radiotherapy.

Undescended testes (cryptorchidism)

Retractile testis

1. Incomplete. Such a testis is arrested in its normal pathway to the scrotum. Usually this is within the inguinal canal, more rarely within the abdomen.

2. Ectopic. An ectopic testis has developed normally, but after passing through the external inguinal ring its further descent is impeded. It either remains in the superficial inguinal pouch (common) or is transposed to perineal, femoral or prepubic sites (rare).

Testicular tumours

Investigations

All suspicious scrotal lumps should be imaged by ultrasound, which provides a high degree of accuracy. As soon as a tumour is suspected, and before orchiectomy, serum levels of AFP, β-HCG and LDH should be determined. The levels of these ‘tumour markers’ are increased in extensive disease. Accurate staging is based on CT of the lungs, liver and retroperitoneal area, and an assessment of renal and pulmonary function (Table 23.4).

Table 23.4 Royal Marsden classification for testicular cancer

Prognosis

Summary Box 23.6 Testicular tumours

• In the UK, there are about 1000 new cases of testicular tumour per year and the 20–40-year age group is predominantly affected

• Seminomas and teratomas account for 85% of all testicular tumours

• Seminomas arise from the seminiferous tubules, are of relatively low-grade malignancy, spread mainly via the lymphatic system and are very sensitive to radiotherapy

• Teratomas arise from germinal cells, their differentiation reflects their aggressiveness (well-differentiated tumours being the least aggressive) and they are not radiosensitive

• Treatment consists of radical orchiectomy (with division of the spermatic cord at the level of the deep inguinal ring). Radiotherapy is used if the tumour proves to be a seminoma, whereas chemotherapy (bleomycin, etoposide and cisplatin) is used for teratomas that are advanced or recurrent

• Seminomas have a 5-year survival rate of 90–95%, whereas teratomas have a more varied prognosis (60–95% 5-year survival rate).

Hydrocoele

This is a common condition, especially in older men, in which fluid collects in the tunica vaginalis, resulting in an enlarged but painless scrotum. The inconvenience of its size usually leads the patient to seek advice. The cause of most hydrocoeles is unknown (idiopathic). The fluid is straw-coloured and protein-rich. In some patients, a hydrocoele develops as a reaction to epididymo-orchitis. Rarely, it may develop with a malignant testis (secondary hydrocoele) and the fluid may then be blood-stained. On examination of the scrotum, a normal spermatic cord can be palpated above a smooth oval swelling. Typically, an idiopathic hydrocoele transilluminates (Fig. 23.23), but where it is long-standing this may be difficult to elicit, owing to fibrosis and thickening of its wall. It is important always to seek this physical sign and also to examine the neck of the scrotum carefully to exclude an inguinal hernia as the cause of the swelling. It may be possible to palpate the testis and confirm that it is normal, but this is unusual as it lies behind and is enveloped by the hydrocoele. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis, then an ultrasound should be performed. Injury to the scrotum may result in a swelling that resembles a hydrocoele but does not transilluminate because the tunica has filled with blood (haematocoele). Aspiration alone does not cure an idiopathic hydrocoele and the tunica soon refills. It is possible to obliterate the sac by injecting a sclerosant after aspiration, but surgical excision and eversion is associated with a much lower recurrence rate. If the hydrocoele fluid becomes infected, incision and drainage of the pus is necessary. Similarly, a haematocoele may require treatment by incision and drainage.

Varicocoele

The veins of the pampiniform plexus are dilated and tortuous, producing a swelling in the line of the spermatic cord that resembles a ‘bag of worms’. It is more common on the left side, possibly because the right-angled drainage of the left testicular vein into the renal vein renders it more liable to stasis. In some men, varicocoele is associated with infertility. A dragging sensation in the scrotum may cause concern. Treatment is by ligation of the spermatic vein, which may be done surgically (laparoscopically) at the internal inguinal ring. Alternatively, the feeding veins can be obliterated radiologically by means of coil embolization (Fig. 23.24).