Urinary tract infections

Bacterial infections of the lower urinary tract

Clinical features of lower urinary tract infections

There are often no localising symptoms in the elderly or the very young, and the patient may be non-specifically unwell. In any ill patient in these age groups, urine must be sent for examination before antibiotics are given. Recurrent fever in a child can result from urinary infection. A sudden onset of enuresis or urinary incontinence in children or the elderly should also suggest bladder infection. Presentations of bladder infection are summarised in Box 38.1.

Recurrent bladder infections

Patients likely to suffer recurrent infections tend to fall into three groups:

• The elderly, debilitated and infirm

• Patients with urinary tract abnormalities predisposing to infection

Upper urinary tract infections

Clinical features of upper urinary tract infections

The classic clinical features of acute pyelonephritis are unilateral loin pain and tenderness (see Box 38.2). The patient is generally unwell with systemic features of infection, i.e. pyrexia and tachycardia. The urine is usually cloudy and there may be typical symptoms of bladder infection. Often the symptoms and signs are less specific, with unilateral abdominal pain or discomfort that may be mistaken for early acute appendicitis unless the urine is examined. Pyelonephritis may present without localising signs, especially in infants and the elderly, who may be more unwell and even develop signs of systemic sepsis.

Management of upper urinary tract infections

Once the acute illness has been treated, further investigation may be indicated to search for predisposing factors. This is usually ultrasonography, CT, sometimes intravenous urography, and flexible cystoscopy. In children, investigation should include a contrast micturating cystogram or equivalent radionuclide scintigram to identify ureteric reflux (see Ch. 51).

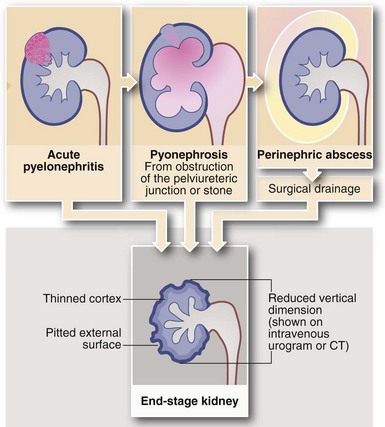

Complications of acute pyelonephritis (see Figs 38.1 and 38.2)

Perinephric abscess

In severe infections, sometimes in the presence of a large ‘staghorn’ calculus, the accumulating pus may discharge through the renal capsule into surrounding fat, resulting in a perinephric abscess (Fig. 38.2). This presents as a slowly expanding loin mass, often with only low-grade local and systemic symptoms. The diagnosis should be considered in elderly patients with sepsis from an unknown source. Urine investigation will reveal pyuria, whilst ultrasound and radiology will show a non-functioning renal mass containing fluid-filled areas. A large renal calculus may also be seen. A perinephric abscess sometimes develops as a result of haematogenous infection of a traumatic perinephric haematoma. The treatment of perinephric abscess is drainage. If a perinephric inflammatory mass partially resolves, it can result in xanthomatous pyelonephritis, a solid mass often suspected of malignancy and hence removed surgically.

Genitourinary tuberculosis

Schistosomiasis

Clinical presentations of schistosomiasis

The main bladder damage caused by schistosomiasis is due to an intense chronic inflammatory reaction to dead ova which have become sequestered in the urothelium. Granulomatous ‘pseudotubercles’ develop around each ovum and later become fibrotic and calcified. Heavy or recurrent infestations result in a variety of destructive lesions including ulcers, papillomata, cysts, giant granulomata and severe bladder contracture. All predispose to secondary bacterial infection and bladder stones. Squamous metaplasia is common and strongly predisposes to carcinoma: two-thirds of these are squamous and one-third transitional cell. The clinical features of urinary schistosomiasis are summarised in Box 38.3.

Urethral infections and strictures

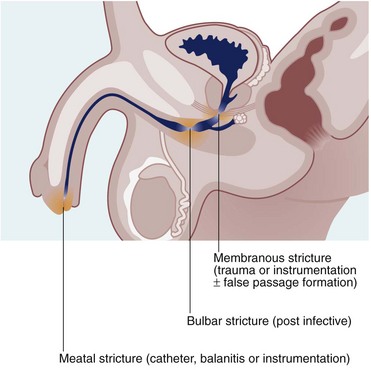

Urethral stricture

Urethral strictures are now most commonly caused by inflammation resulting from iatrogenic trauma. Transurethral resection for prostatic surgery is the most common cause. Urinary catheterisation in patients with poor tissue perfusion is another common cause, particularly during cardiopulmonary bypass for cardiac surgery. Iatrogenic strictures involve the distal urethra or the meatus. Strictures may also be a complication of traumatic instrumentation, where the membranous urethra is most vulnerable (see Fig. 38.3). A few strictures result from urethral tearing or rupture following displaced pelvic fractures. These usually require open surgical reconstruction.