16.4 Urinary tract infection in pre-school children

Introduction

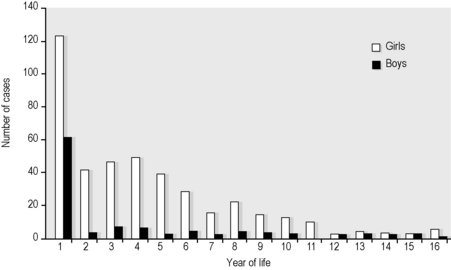

Data from Sweden suggest that in the first 2 years of life, up to 3% of infants may suffer UTI. Between 1 and 10 years of age 3–8% of girls and < 1% of boys will have at least one urine infection. It is important to remember that recurrences are common. UTI is more frequent in boys than girls in the first months of life, partly because of a higher incidence of obstruction including pelviureteric junction obstruction, thereafter occurring significantly more often in girls (Fig. 16.4.1).

Fig. 16.4.1 Epidemiology of UTI in childhood. Cases recorded in Gothenburg 1960–1966.

Source: Winberg J, Andersen HJ, Bergström T, et al. Acta Paediatrica Scandinavia Supplement 1974;63(Suppl. 252):1?20.

Renal involvement is associated with:

Long-term complications of renal scarring include: pregnancy-associated problems; hypertension; and, rarely, chronic renal insufficiency (see prognosis section below).

History and examination

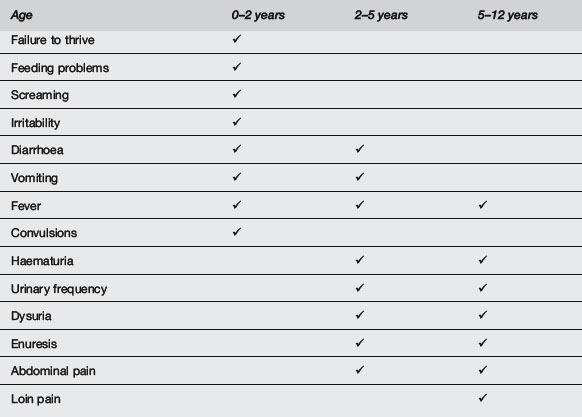

In infants and young children with UTI, the clinical history is frequently non-specific and may include irritability, jaundice (neonates), poor feeding or fever without apparent source. Symptoms and signs become more specific with increasing age (Table 16.4.1).

Diagnosis

The definition of significant bacteriuria is guided by the method by which the urine specimen was collected (Table 16.4.2), though on occasion genuine UTI may be present with lower colony counts than would usually be considered significant, especially in babies – interpret results in light of history and clinical findings.

Treatment

ED treatment recommendations for UTI vary. However, one approach is as follows.

Age <6 months

Age 6–12 months

Management after discharge from ED or observation wards

Most centres will have a referral, management and investigation protocol which should be followed. Many of these are based on the National Institute for Clinical Excellence Guidelines from the United Kingdom,1 though significant variation exists from place to place. In the absence of local guidelines, the following approach is reasonable.

Arrange a ‘proof of cure’ urine culture after stopping antibiotic.

Prognosis

At least some of these consequences may be preventable by early and effective diagnosis and treatment of UTI in very young children (though even this has been questioned by some authors5).

Prevention

Controversies and future directions

‘There is no subject in which there is so little uniformity of opinion and so much confusion.’ This statement made in 1916 is seemingly just as pertinent in the early 21st century, with many questions about paediatric UTI management still the subject of debate and controversy. On the specific subject of VUR, one author, considering ‘the effect of scientific evidence on clinical decision making in children with VUR during the past 40 years’ (since its description), suggests that ‘reported data have been overlooked in favour of unfounded speculation or clinical tradition’.5

‘There is no subject in which there is so little uniformity of opinion and so much confusion.’ This statement made in 1916 is seemingly just as pertinent in the early 21st century, with many questions about paediatric UTI management still the subject of debate and controversy. On the specific subject of VUR, one author, considering ‘the effect of scientific evidence on clinical decision making in children with VUR during the past 40 years’ (since its description), suggests that ‘reported data have been overlooked in favour of unfounded speculation or clinical tradition’.51 NICE Guidelines. Urinary tract infection: diagnosis, treatment and long-term management of urinary tract infection in children. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk/CG054 [accessed 21.10.10]

2 Smellie J., Edwards D., Hunter N., et al. Vesico-ureteric reflux and renal scarring. Kid IntSuppl. 1975;4:65-72.

3 Malek R.S., Svensson J., Neves R.J., Torres V.E. Vesicoureteral reflux in the adult. III. Surgical correction: benefits. J Urol. 1983;130:882-886.

4 Noe H.N. The current status of screening for vesicoureteral reflux. Paediatr Nephrol. 1995;9:638-641.

5 Hewitt I.K., Zucchetta P., Rigon L., et al. Early treatment of acute pyelonephritis in children fails to reduce renal scarring: data from the Italian renal infection study trials. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):486-490.

Bachur R., Caputo G.L. Bacteraemia and meningitis among infants with urinary tract infection. Paediatr Emerg Care. 1995;11:280-284.

Crabtree E.G., Cabot H. Colon bacillus pyelonephritis: Its nature and possible prevention. Transactions of the Section of Genitourinary Diseases of the American Medical Association, vol 57. 1916:209-217.

Crain E.F., Gershel J.C. Urinary tract infections in febrile infants younger than 8 weeks. Paediatrics. 1990;86:363-367.

Doley A., Neligan M. Is a negative dipstick urinalysis good enough to exclude urinary tract infection in paediatric ED patients? Emerg Med. 2003;15:77-80.

Hodson E.M., Wheeler D.M., Vimalchandra D., et al. Interventions for primary vesicoureteric reflux. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (3):2007. CD001532

Jakobsson B., Esbjorner E., Hansson S. Minimum incidence and diagnostic rate of first urinary tract infection. Paediatrics. 2000;106:620-621.

Kinney A.B., Blount M. Effect of cranberry juice on urinary pH. Nurs Res. 1979;28:287-290.

Montini G., Zucchetta P., Tomasi L., et al. Value of imaging studies after a first febrile urinary tract infection in young children: data from Italian renal infection study 1. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2):e239-e246. Epub 2009 Jan 12

Pollack C.V., Pollack E.S., Andrew M.E. Suprapubic bladder aspiration versus urethral catheterization in infants: Success, efficiency and complication rates. Ann Emerg Med. 1994;23:225-230.

Shihab Z.M. Urinary tract infection. In: Barakat A.Y., editor. Renal disease in children – clinical evaluation & diagnosis. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1990:157-170.

Sobota A.E. Inhibition of bacterial adherence by cranberry juice: Potential for treatment of urinary tract infections. J Urol. 1984;131:1013-1016.

Willis F.R., Geelhoed G.C. Urinary tract infection. In: Management guidelines – Emergency Department. Perth, Western Australia: Princess Margaret Hospital for Children; 2002.