Urinalysis

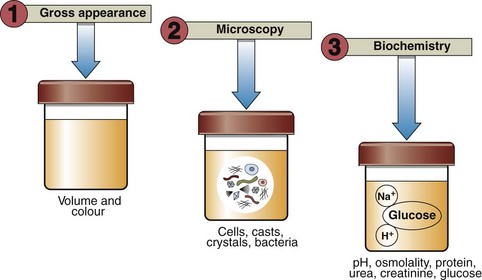

Urinalysis is so important in screening for disease that it is regarded as an integral part of the complete physical examination of every patient, and not just in the investigation of renal disease. Urinalysis comprises a range of analyses that are usually performed at the point of care rather than in a central laboratory. Examination of a patient’s urine should not be restricted to biochemical tests. Figure 16.1 summarizes the different ways urine may be examined.

Procedure

Biochemical testing of urine involves the use of commercially available disposable strips (Fig 16.2). Each strip is impregnated with a number of coloured reagent ‘blocks’ separated from each other by narrow bands. When the strip is manually immersed in the urine specimen, the reagents in each block react with a specific component of urine in such a way that (a) the block changes colour if the component is present, and (b) the colour change produced is proportional to the concentration of the component being tested for.

Fig 16.2 Multistix testing of a urine sample: (a) Immersion of test strip in urine specimen. (b) Excess urine removed. (c) Test strip is compared with colour chart on bottle label.

fresh urine is collected into a clean dry container

fresh urine is collected into a clean dry container

the disposable strip is briefly immersed in the urine specimen; care must be taken to ensure that all reagent blocks are covered

the disposable strip is briefly immersed in the urine specimen; care must be taken to ensure that all reagent blocks are covered

the edge of the strip is held against the rim of the urine container to remove any excess urine

the edge of the strip is held against the rim of the urine container to remove any excess urine

the strip is then held in a horizontal position for a fixed length of time that varies from 30 seconds to 2 minutes

the strip is then held in a horizontal position for a fixed length of time that varies from 30 seconds to 2 minutes

the colour of the test areas are compared with those provided on a colour chart (Fig 16.2). The strip is held close to the colour blocks on the chart and matched carefully, and then discarded.

the colour of the test areas are compared with those provided on a colour chart (Fig 16.2). The strip is held close to the colour blocks on the chart and matched carefully, and then discarded.

pH (hydrogen ion concentration)

Urine is usually acidic (urine pH substantially less than 7.4 indicating a high concentration of hydrogen ions). Measurement of urine pH is useful either in cases of suspected adulteration, e.g. drug abuse screens, or where there is an unexplained metabolic acidosis (low serum bicarbonate). The renal tubules normally excrete hydrogen ions by mechanisms that ensure tight regulation of the blood hydrogen ion concentration. Where one or more of these mechanisms fail, an acidosis results (so-called renal tubular acidosis or RTA; see p. 30). Measurement of urine pH may, therefore, be used to screen for RTA in unexplained metabolic acidosis; a pH less than 5.3 indicates that the renal tubules are able to acidify urine and are, therefore, unlikely to be responsible.

Protein

Proteinuria may signify abnormal excretion of protein by the kidneys (due either to abnormally ‘leaky’ glomeruli or to the inability of the tubules to reabsorb protein normally), or it may simply reflect the presence in the urine of cells or blood. For this reason it is important to check that the dipstick test is not also positive for blood or leucocytes (white cells); it may also be appropriate to screen for a urinary tract infection by sending urine for culture. Proteinuria and its causes are discussed in detail on pages 34–35.