228 Uraemia

Instruction

Would you like to ask this uraemic patient some questions and perform a relevant examination?

Salient features

History

• Loss of appetite, anorexia, nausea, vomiting and hiccups

• Fatigue, malaise, loss of energy

• Polyuria, nocturia, dysuria, haematuria, difficulty in passing urine

• Swelling of the face and feet

• Shortness of breath (from secondary left ventricular failure)

• Restless legs (overwhelming need to frequently alter position of legs)

• Paraesthesia from either hypocalcaemia (associated tetany) or peripheral neuropathy

• Bone pain (from metabolic bone disease)

• Drug history, in particular NSAIDs, tetracycline

• History of diabetes, hypertension, recurrent urinary tract infections

• Family history of renal disease, in particular polycystic kidneys

• Tell the examiner that you would like to take a history for impotence in men and ameonorrhoea in women.

Examination

• Comment on short stature (indicates uraemia from childhood)

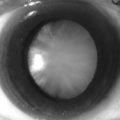

• Examine the nails (for Lindsay’s ‘half-and-half’ nails where the proximal portion is whitish while the distal portion is brownish red; the lunula is usually obscured)

• Comment on the lemon tinge of the skin, the pallor and scratch marks. Rarely, there may be ‘uraemic frost’: increased photosensitive skin pigmentation

• Examine the arms for asterixis (flapping tremor), haemodialysis fistula

• Comment on the vascular shunts, if any

• Comment on hyperventilation of Kussmaul’s respiration secondary to metabolic acidosis

• Examine the abdomen for palpable kidneys (hydronephrosis, polycystic kidneys) and palpable bladder

• Check for pitting leg oedema

• Tell the examiner that you would like to proceed as follows:

Questions

How would you investigate a patient with renal failure?

• Urine: glucose, microscopy, specific gravity, creatinine clearance, 24-hour urinary protein, urine electrophoresis

• Serum: urea, electrolytes, creatinine, protein, calcium phosphate, uric acid

• Ultrasonography of the abdomen for kidneys, bladder

• Special investigations: pyelography, protein electrophoresis, complement components, autoantibody screening, serum cryoglobulins, kidney biopsy.

What do you understand by the term uraemia?

Uraemia implies a deterioration of renal function associated with symptoms (GFR <20% of normal).

What is the classification of chronic kidney disease?

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is classified based on clinical parameters and the GFR.

| Stage | Description | Estimated GFR (ml/min per 1.73m2) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Normal or increased GFR, with other evidence of kidney damage | ≥90 |

| 2 | Slight decrease in GFR, with other evidence of kidney damage | 60–89 |

| 3 | Moderate decrease in GFR, with or without other evidence of kidney damage | 30–59 |

| 4 | Severe decrease in GFR, with or without other evidence of kidney damage | 15–29 |

| 5 | Established in renal failure | <15 |

Advanced-level questions

Mention a few drugs that you would avoid in renal failure

Aminoglycosides, furosemide with cephalosporins, potassium salts, tetracycline.

What are the consequences of renal failure?

• Metabolic: sodium imbalance, hyperkalaemia, metabolic acidosis, hyperuricaemia, hypocalcaemia, hypermagnesaemia, hyperphosphataemia

• Cardiovascular: left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), cardiac failure, hypertension, accelerated atherosclerosis, pericarditis. (Pericarditis is either uraemic pericarditis or dialysis pericarditis.) LVH in large part results from hypertension, expansion of extracellular volume and anaemia. The LVH may be accompanied by left ventricular remodelling and fibrosis, and these changes, with or without coronary artery disease, may lead to cardiac failure, myocardial infarction or sudden death

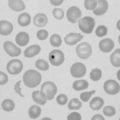

• Haematological: anaemia, clotting disorders, leukocyte abnormalities

• Skin: itching, hyperpigmentation, bruising

• Nervous system: encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy, autonomic neuropathy

• GI: anorexia, nausea, vomiting, peptic ulcer, diarrhoea, constipation (particularly in patients on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis

• Endocrine: vitamin D disorders, secondary hyperparathyroidism, impotence, amenorrhoea, glucose intolerance.

What are the mechanisms underlying the progression from early-stage to advanced chronic kidney disease?

• Progressive glomerulosclerosis and interstitial fibrosis result in the progression from early CKD to advanced CKD.

• Loss of renal mass results in haemodynamic adaptations, activation of the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, systemic hypertension, proteinuria and hyperlipidaemia.

• These adaptations result in increased inflammation and oxidative stress, with upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and growth factors, their receptors, or both; the increased inflammation and oxidative stress stimulate cell hypertrophy and proliferation and inflammatory-cell infiltration.

• Some of these early adaptations (such as haemodynamic and hypertrophic responses) become maladaptive and eventually contribute to the structural and functional changes in the kidney that are characteristic of advanced CKD.

What is the management of stage 4 chronic kidney disease?

• Therapy with an angiotensin receptor blocker or an ACE inhibitor, with the medication adjusted to achieve a BP below 130/80 mmHg (reduction of BP to this level slows the rate of decline in GFR even in patients with advanced CKD). A thiazide diuretic should be replaced by a loop diuretic; if the targeted BP is not reached, a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or both should be added

• Dietary protein should be limited to approximately 0.8 to 1.0 g per kilogram/day

• Treatment of hyperlipidaemia with a statin and aspirin therapy to reduce the likelihood of cardiovascular disease

• Anaemia: target haemoglobin concentration of 110–120 g/l. Iron deficiency should be assessed and treated

• Serum phosphate levels should be monitored; if >46 mg/l (1.5 mmol/l), a phosphate binder should be added to the therapeutic regimen

• Low-dose active vitamin D analogue will help to control secondary hyperparathyroidism

• Serum bicarbonate <20 mmol/l and systemic acidaemia should be treated with sodium bicarbonate

• Patients should be educated about methods of renal replacement therapy, and efforts should be made to preserve the venous circulation in the upper extremities in order to maintain vascular access in those patients who opt for haemodialysis.

When would you consider dialysis?

What are the bone changes in chronic renal failure?

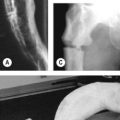

• Osteomalacia (renal rickets)

• Osteitis fibrosa cystica (secondary hyperparathyroidism): subperiosteal erosions, especially of the skull (pepperpot skull), phalanges, long bones and distal end of clavicles

• Osteosclerosis: enhanced density of the bone in the upper and lower margins of vertebrae (rugger-jersey spine).

Is there any benefit in restricting dietary protein in chronic renal disease?

A large randomized controlled trial suggested no benefit from protein restriction.

How are the beneficial effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors in renal disease produced?

What criteria are used to assess acute renal failure?

The RIFLE criteria

Based on GFR or urine output or both plus urine output on a body weight basis:

Risk: serum creatinine increase 150%, GFR decrease <25%, urine output <0.5 ml/h per kg over 6 h

Injury: serum creatinine 200%, GFR decrease <50%, urine output <0.5 ml/h per kg over 12 h

Failure: serum creatinine 300%, GFR decrease <75%, urine output <0.3 ml/h per kg over 24 h or anuria for 12 h

The AKIN criteria

The Acute Kidney Injury Network (AKIN) modifies the RIFLE scheme to exclude GFR:

I: serum creatinine increase ≥150% (>3.0 mg/l)

II: serum creatinine increase ≥200%

III: serum creatinine increase >300% or >40 mg/l in the setting of an increase of ≥50 mg/l.

I is equivalent to risk, II to injury and III to failure on the RIFLE scale.