Upper Limb

ADDITIONAL LEARNING RESOURCES for Chapter 7, Upper Limb, on STUDENT CONSULT (www.studentconsult.com):

Conceptual overview

General description

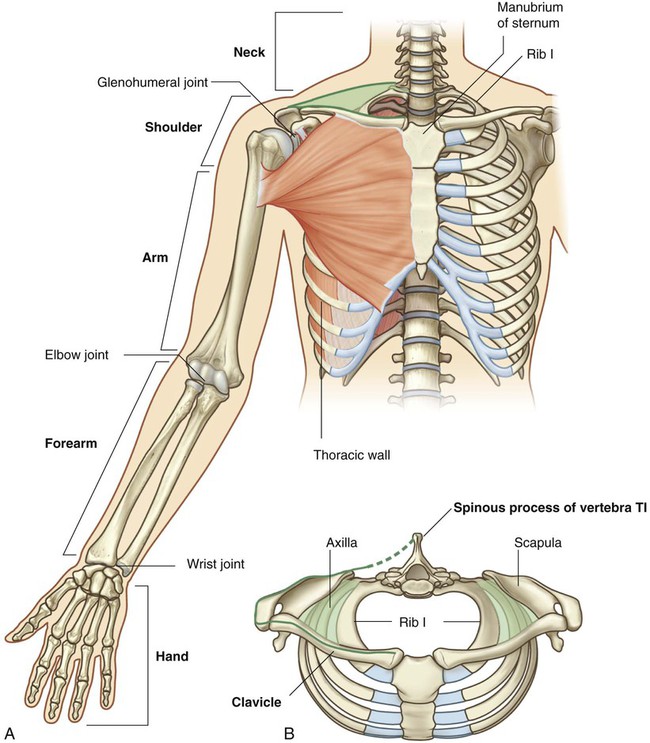

The upper limb is associated with the lateral aspect of the lower portion of the neck and with the thoracic wall. It is suspended from the trunk by muscles and a small skeletal articulation between the clavicle and the sternum—the sternoclavicular joint. Based on the position of its major joints and component bones, the upper limb is divided into shoulder, arm, forearm, and hand (Fig. 7.1A).

The shoulder is the area of upper limb attachment to the trunk (Fig. 7.1B).

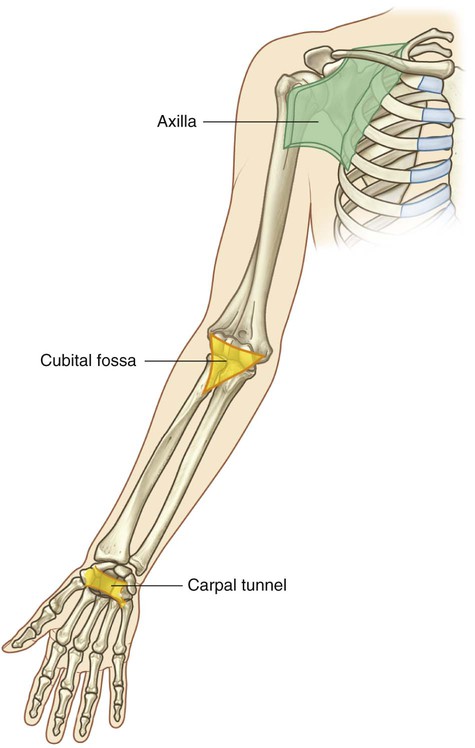

The axilla, cubital fossa, and carpal tunnel are significant areas of transition between the different parts of the limb (Fig. 7.2). Important structures pass through, or are related to, each of these areas.

Functions

Positioning the hand

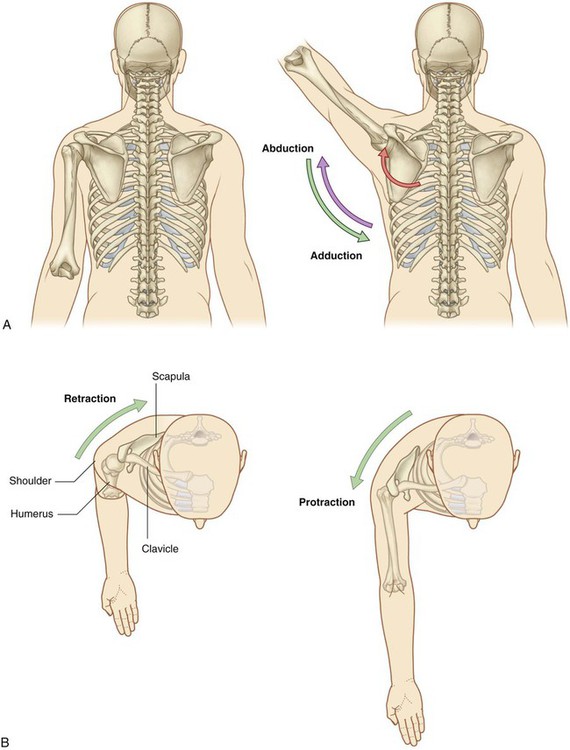

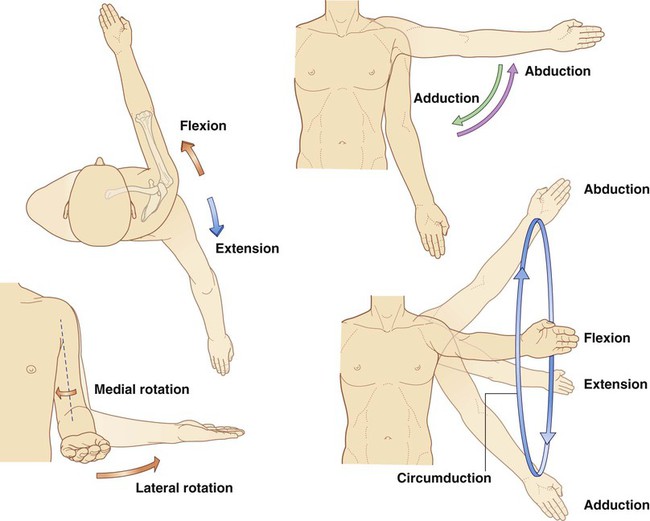

The shoulder is suspended from the trunk predominantly by muscles and can therefore be moved relative to the body. Sliding (protraction and retraction) and rotating the scapula on the thoracic wall changes the position of the glenohumeral joint (shoulder joint) and extends the reach of the hand (Fig. 7.3). The glenohumeral joint allows the arm to move around three axes with a wide range of motion. Movements of the arm at this joint are flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial rotation (internal rotation), lateral rotation (external rotation), and circumduction (Fig. 7.4).

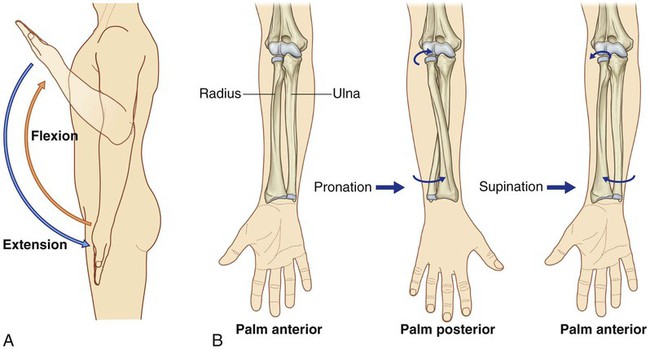

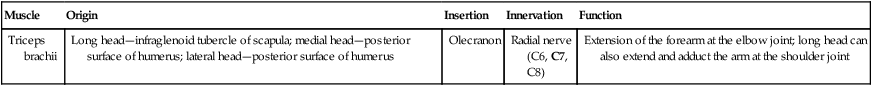

The major movements at the elbow joint are flexion and extension of the forearm (Fig. 7.5A). At the other end of the forearm, the distal end of the lateral bone, the radius, can be flipped over the adjacent head of the medial bone, the ulna. Because the hand is articulated with the radius, it can be efficiently moved from a palm-anterior position to a palm-posterior position simply by crossing the distal end of the radius over the ulna (Fig. 7.5B). This movement, termed pronation, occurs solely in the forearm. Supination returns the hand to the anatomical position.

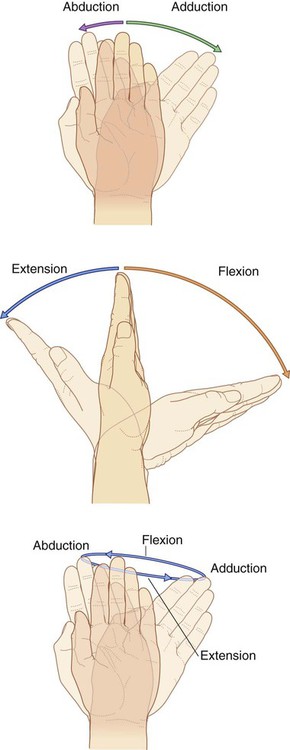

At the wrist joint, the hand can be abducted, adducted, flexed, extended, and circumducted (Fig. 7.6). These movements, combined with those of the shoulder, arm, and forearm, enable the hand to be placed in a wide range of positions relative to the body.

Component parts

Bones and joints

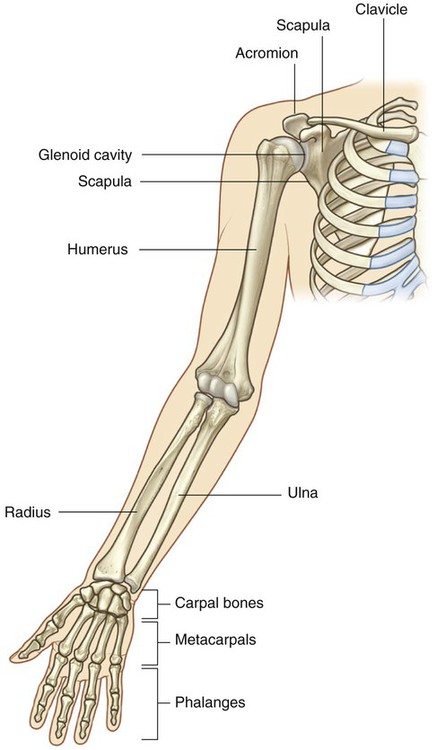

The bones of the shoulder consist of the scapula, clavicle, and proximal end of the humerus (Fig. 7.7).

The humerus is the bone of the arm (Fig. 7.7). The distal end of the humerus articulates with the bones of the forearm at the elbow joint, which is a hinge joint that allows flexion and extension of the forearm.

The forearm contains two bones:

The bones of the hand consist of the carpal bones, the metacarpals, and the phalanges (Fig. 7.7).

The five digits in the hand are the thumb and the index, middle, ring, and little fingers.

The five metacarpals, one for each digit, are the primary skeletal foundation of the palm (Fig. 7.7).

The bones of the digits are the phalanges (Fig. 7.7). The thumb has two phalanges, while each of the other digits has three.

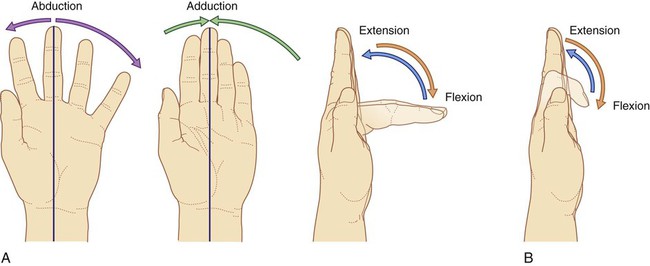

The metacarpophalangeal joints are biaxial condylar joints (ellipsoid joints) that allow abduction, adduction, flexion, extension, and circumduction (Fig. 7.8). Abduction and adduction of the fingers is defined in reference to an axis passing through the center of the middle finger in the anatomical position. The middle finger can therefore abduct both medially and laterally and adduct back to the central axis from either side. The interphalangeal joints are primarily hinge joints that allow only flexion and extension.

Muscles

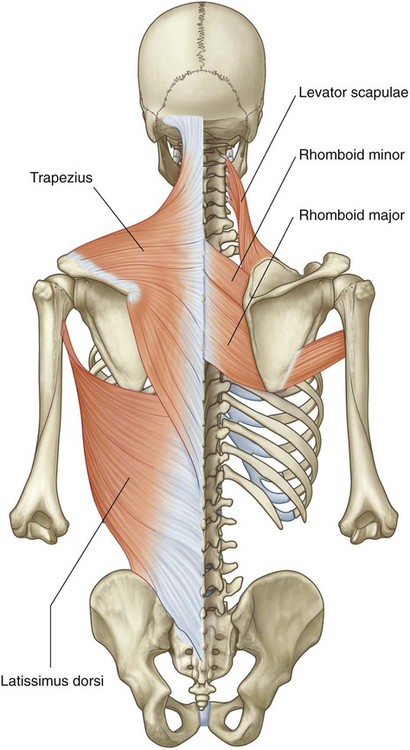

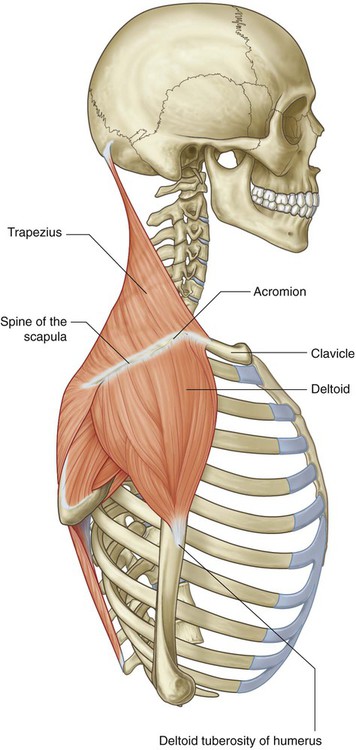

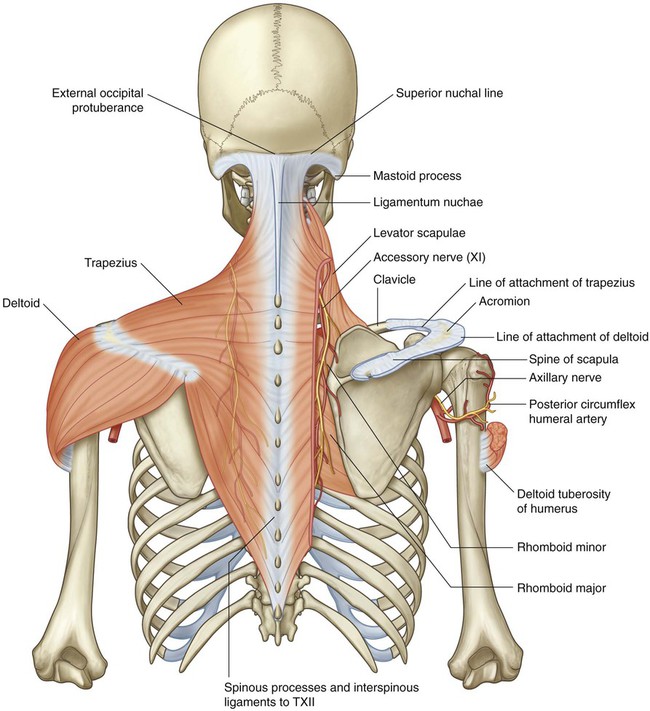

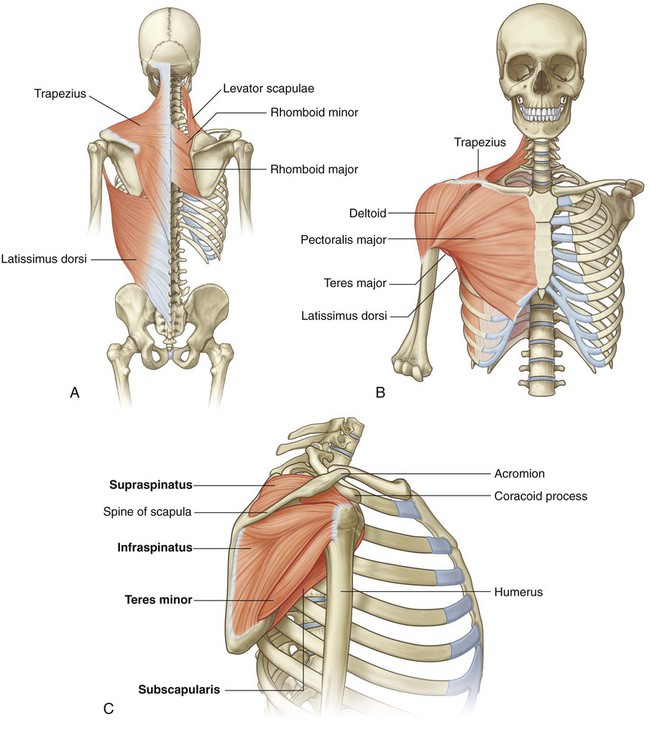

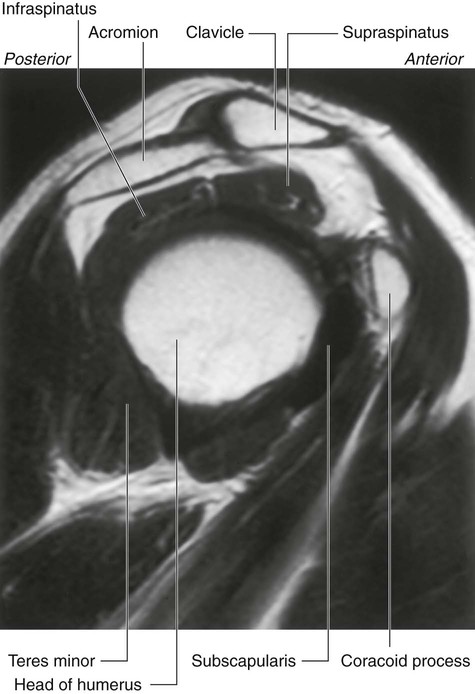

Some muscles of the shoulder, such as the trapezius, levator scapulae, and rhomboids, connect the scapula and clavicle to the trunk. Other muscles connect the clavicle, scapula, and body wall to the proximal end of the humerus. These include the pectoralis major, pectoralis minor, latissimus dorsi, teres major, and deltoid (Fig. 7.9A,B). The most important of these muscles are the four rotator cuff muscles—the subscapularis, supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor muscles—which connect the scapula to the humerus and provide support for the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 7.9C).

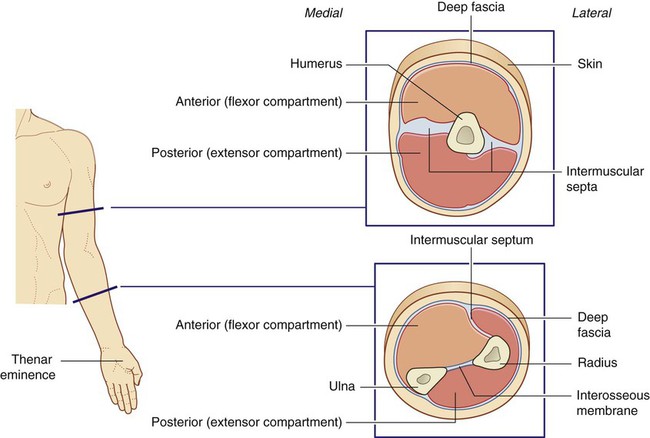

Muscles in the arm and forearm are separated into anterior (flexor) and posterior (extensor) compartments by layers of fascia, bones, and ligaments (Fig. 7.10).

In the forearm, the anterior and posterior compartments are separated by a lateral intermuscular septum, the radius, the ulna, and an interosseous membrane, which joins adjacent sides of the radius and ulna (Fig. 7.10).

Relationship to other regions

Neck

the posterior surface of the clavicle,

the posterior surface of the clavicle,

the superior margin of the scapula, and

the superior margin of the scapula, and

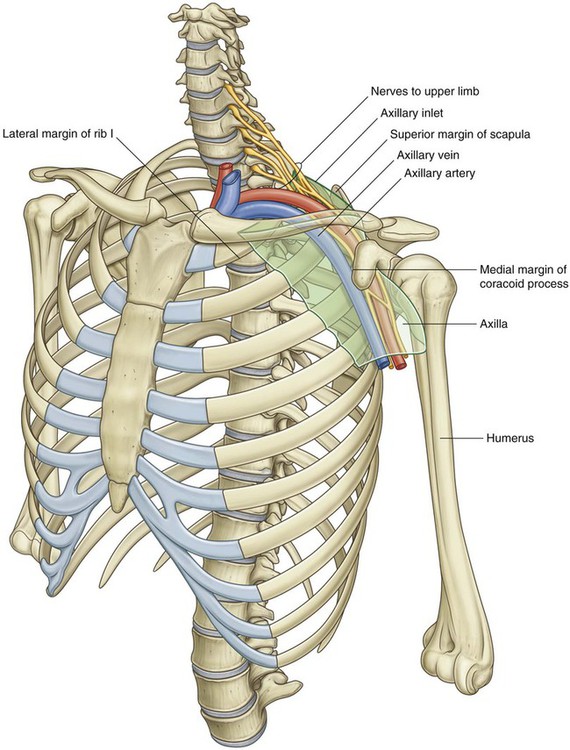

the medial surface of the coracoid process of the scapula (Fig. 7.11).

the medial surface of the coracoid process of the scapula (Fig. 7.11).

Back and thoracic wall

Muscles that attach the bones of the shoulder to the trunk are associated with the back and the thoracic wall and include the trapezius, levator scapulae, rhomboid major, rhomboid minor, and latissimus dorsi (Fig. 7.12).

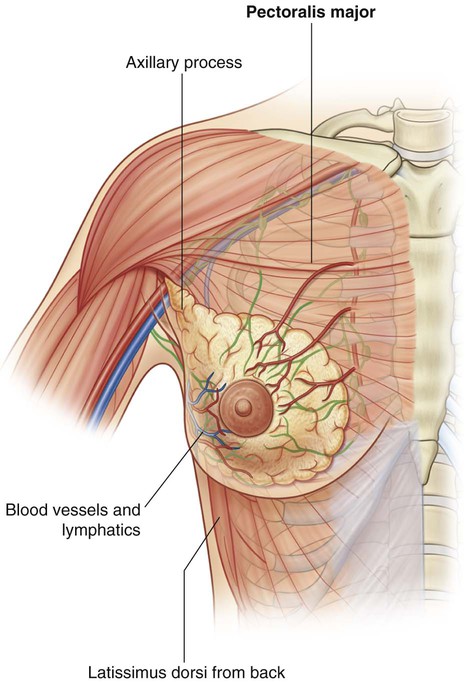

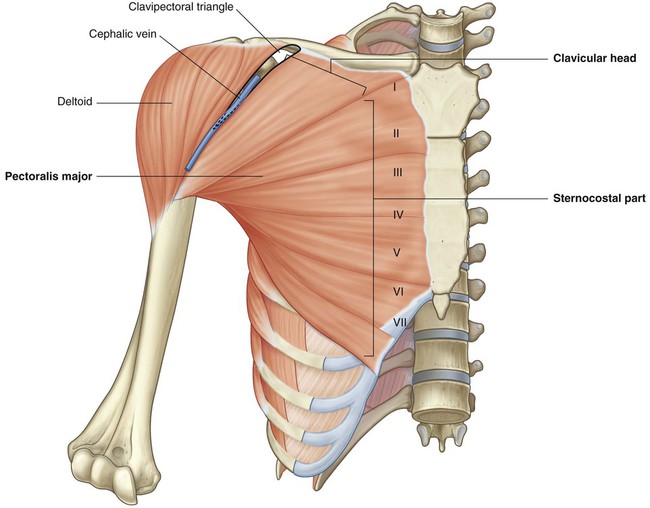

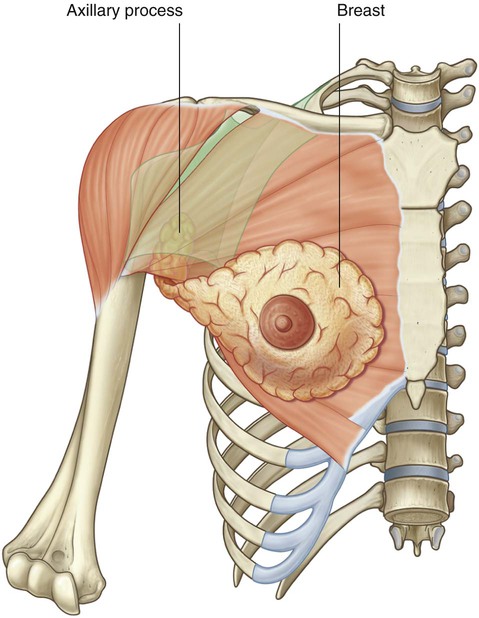

The breast on the anterior thoracic wall has a number of significant relationships with the axilla and upper limb. It overlies the pectoralis major muscle, which forms most of the anterior wall of the axilla and attaches the humerus to the chest wall (Fig. 7.13). Often, part of the breast known as the axillary process extends around the lateral margin of the pectoralis major into the axilla.

Key points

Innervation by cervical and upper thoracic nerves

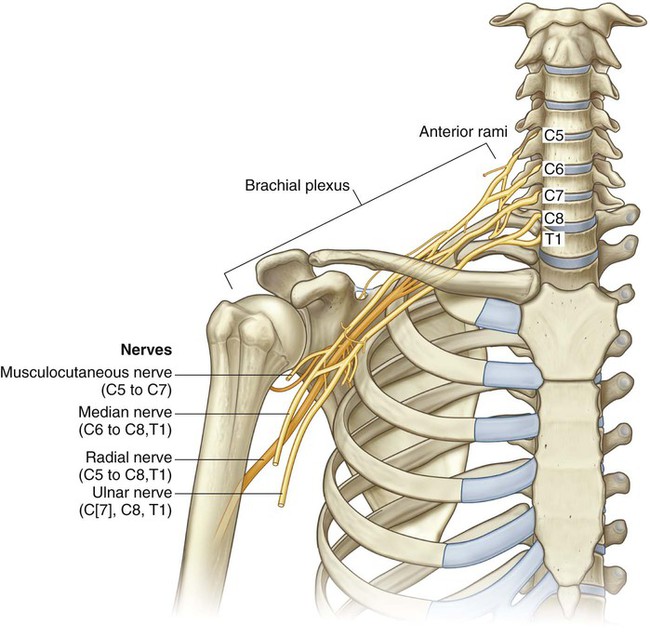

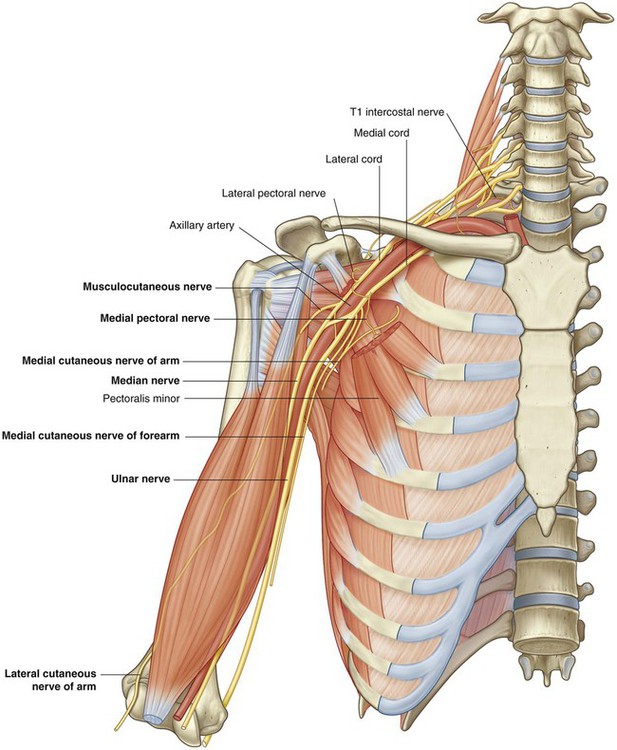

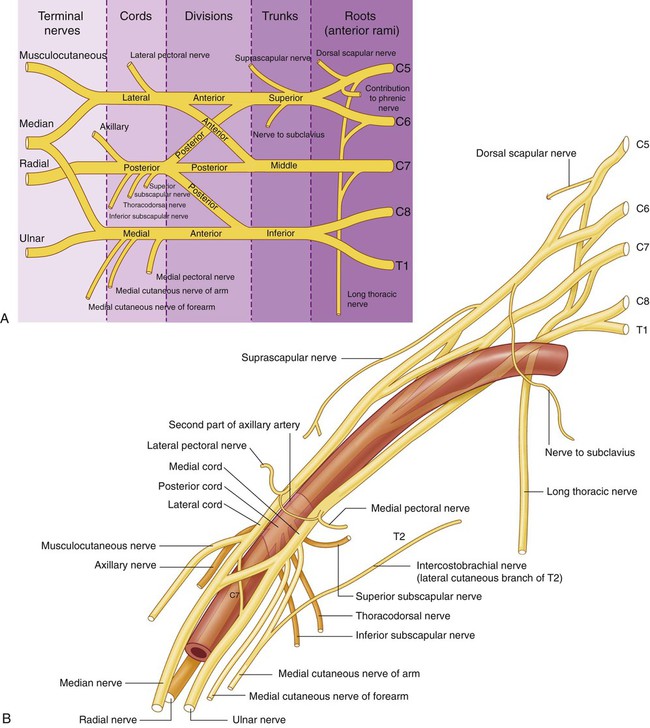

Innervation of the upper limb is by the brachial plexus, which is formed by the anterior rami of cervical spinal nerves C5 to C8, and T1 (Fig. 7.14). This plexus is initially formed in the neck and then continues through the axillary inlet into the axilla. Major nerves that ultimately innervate the arm, forearm, and hand originate from the brachial plexus in the axilla.

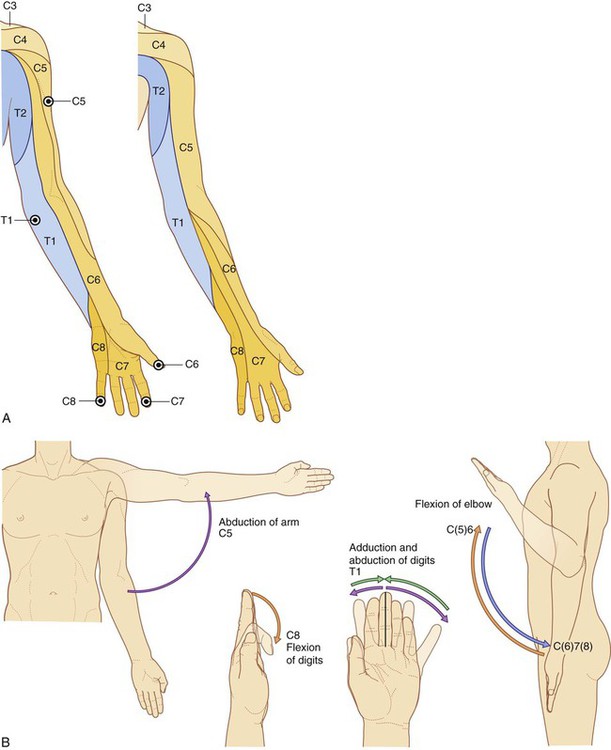

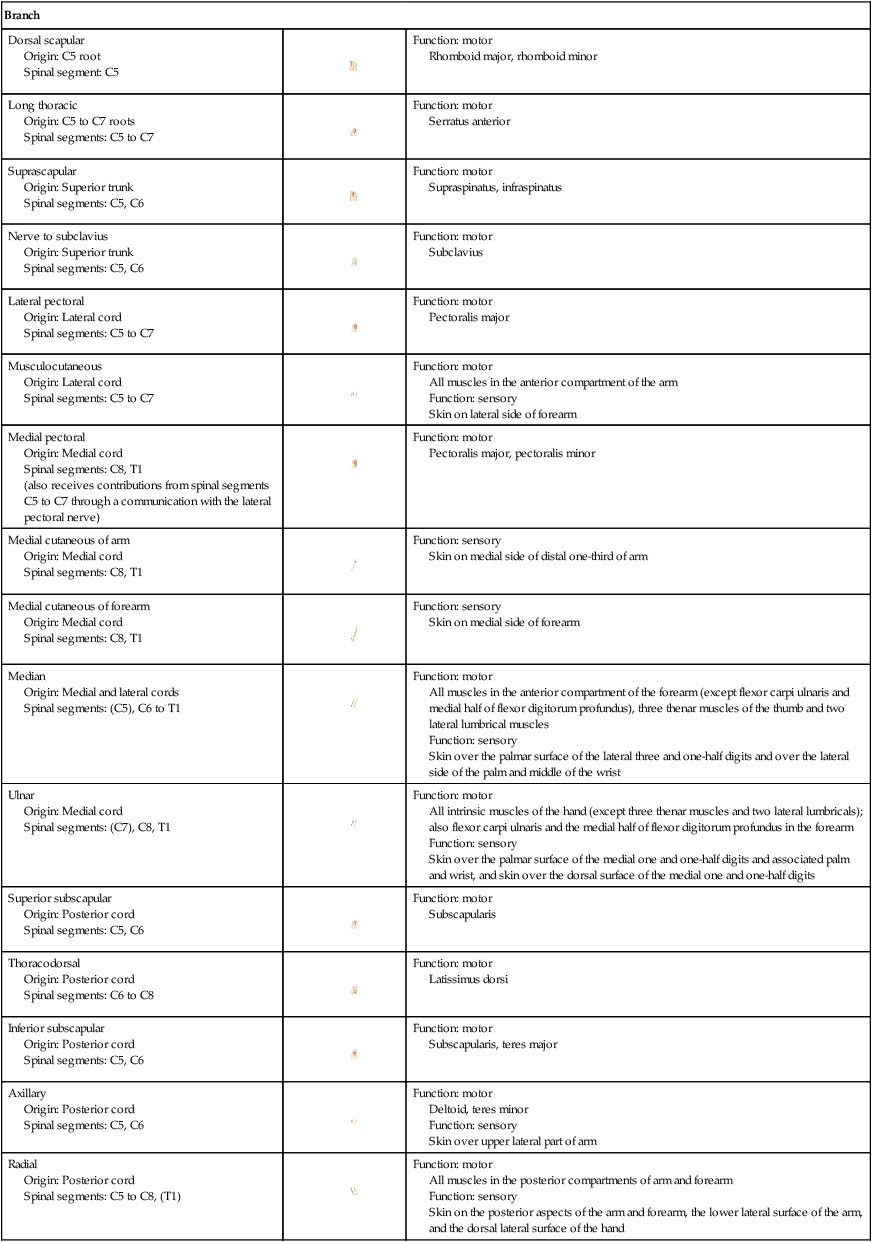

Dermatomes of the upper limb (Fig. 7.15A) are often tested for sensation. Areas where overlap of dermatomes is minimal include the:

upper lateral region of the arm for spinal cord level C5,

upper lateral region of the arm for spinal cord level C5,

palmar pad of the thumb for spinal cord level C6,

palmar pad of the thumb for spinal cord level C6,

pad of the index finger for spinal cord level C7,

pad of the index finger for spinal cord level C7,

pad of the little finger for spinal cord level C8, and

pad of the little finger for spinal cord level C8, and

skin on the medial aspect of the elbow for spinal cord level T1.

skin on the medial aspect of the elbow for spinal cord level T1.

Selected joint movements are used to test myotomes (Fig. 7.15B):

Abduction of the arm at the glenohumeral joint is controlled predominantly by C5.

Abduction of the arm at the glenohumeral joint is controlled predominantly by C5.

Flexion of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled primarily by C6.

Flexion of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled primarily by C6.

Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled mainly by C7.

Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint is controlled mainly by C7.

Flexion of the fingers is controlled mainly by C8.

Flexion of the fingers is controlled mainly by C8.

Abduction and adduction of the index, middle, and ring fingers is controlled predominantly by T1.

Abduction and adduction of the index, middle, and ring fingers is controlled predominantly by T1.

A tap on the tendon of the biceps in the cubital fossa tests mainly for spinal cord level C6.

A tap on the tendon of the biceps in the cubital fossa tests mainly for spinal cord level C6.

A tap on the tendon of the triceps posterior to the elbow tests mainly for C7.

A tap on the tendon of the triceps posterior to the elbow tests mainly for C7.

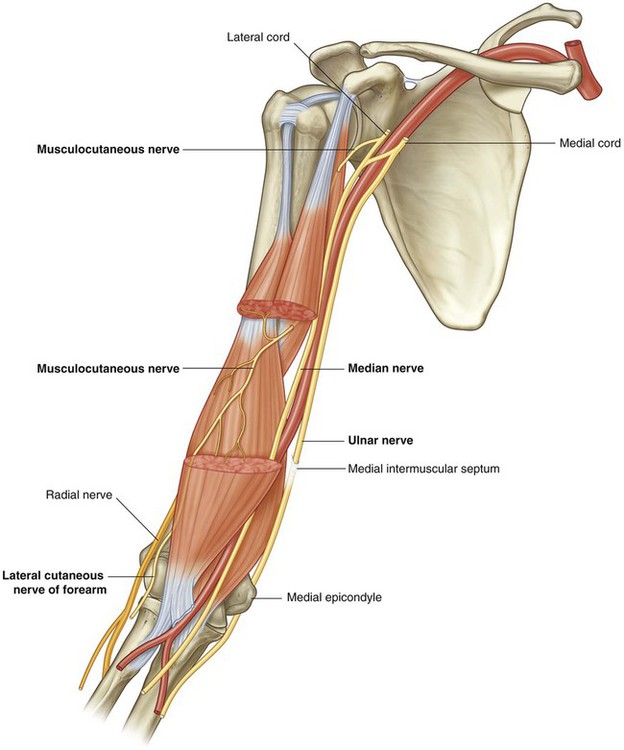

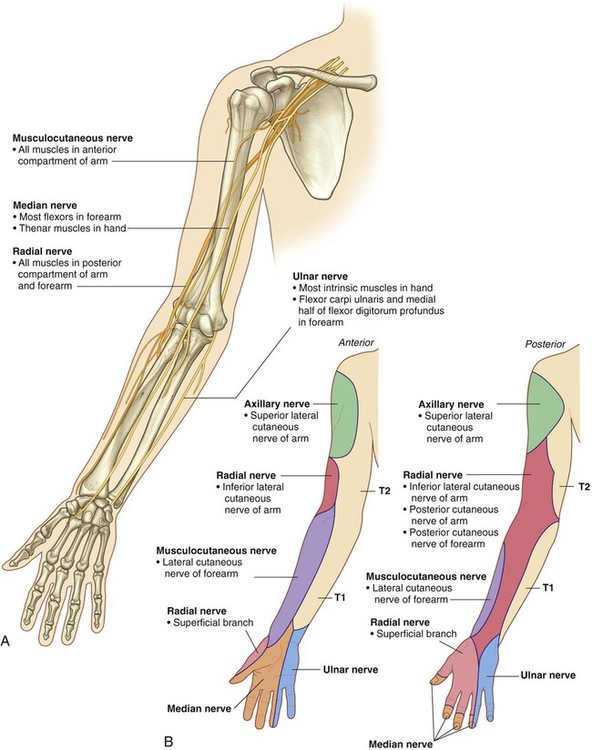

Each of the major muscle compartments in the arm and forearm and each of the intrinsic muscles of the hand is innervated predominantly by one of the major nerves that originate from the brachial plexus in the axilla (Fig. 7.16A):

All muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm are innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

All muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm are innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

The median nerve innervates the muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm, with two exceptions—one flexor of the wrist (the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle) and part of one flexor of the fingers (the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle) are innervated by the ulnar nerve.

The median nerve innervates the muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm, with two exceptions—one flexor of the wrist (the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle) and part of one flexor of the fingers (the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle) are innervated by the ulnar nerve.

Most intrinsic muscles of the hand are innervated by the ulnar nerve, except for the thenar muscles and two lateral lumbrical muscles, which are innervated by the median nerve.

Most intrinsic muscles of the hand are innervated by the ulnar nerve, except for the thenar muscles and two lateral lumbrical muscles, which are innervated by the median nerve.

All muscles in the posterior compartments of the arm and forearm are innervated by the radial nerve.

All muscles in the posterior compartments of the arm and forearm are innervated by the radial nerve.

In addition to innervating major muscle groups, each of the major peripheral nerves originating from the brachial plexus carries somatic sensory information from patches of skin quite different from dermatomes (Fig. 7.16B). Sensation in these areas can be used to test for peripheral nerve lesions:

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates skin on the anterolateral side of the forearm.

The musculocutaneous nerve innervates skin on the anterolateral side of the forearm.

The median nerve innervates the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the medial one and one-half digits.

The median nerve innervates the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits, and the ulnar nerve innervates the medial one and one-half digits.

The radial nerve supplies skin on the posterior surface of the forearm and the dorsolateral surface of the hand.

The radial nerve supplies skin on the posterior surface of the forearm and the dorsolateral surface of the hand.

Nerves related to bone

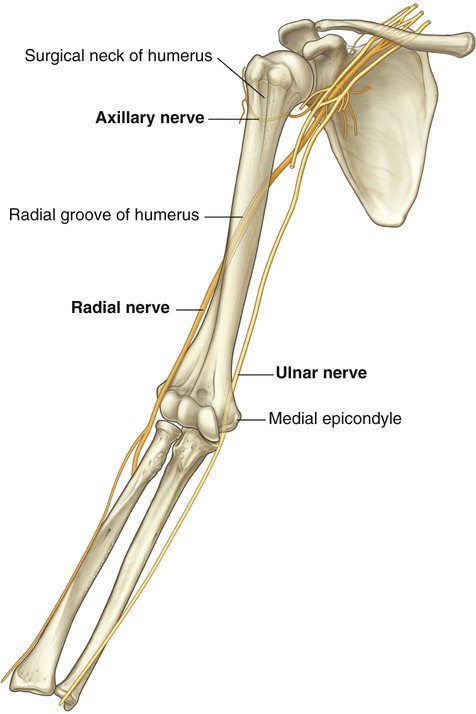

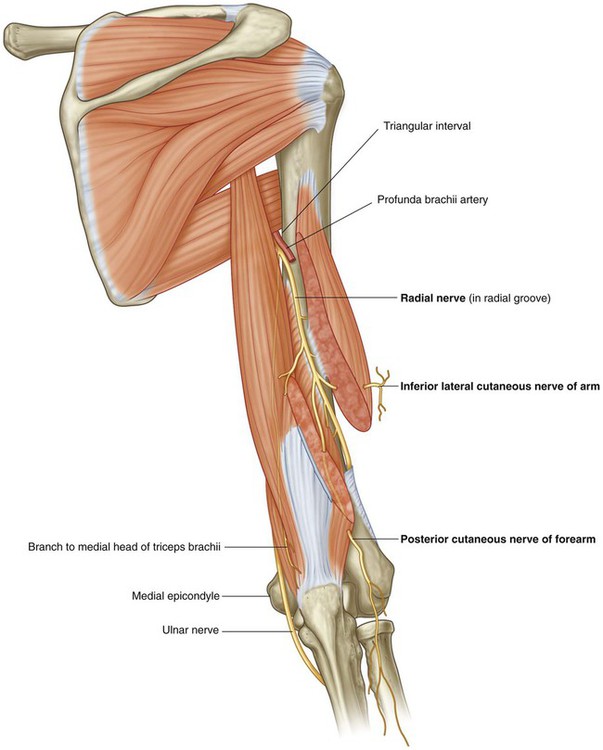

Three important nerves are directly related to parts of the humerus (Fig. 7.17):

The axillary nerve, which supplies the deltoid muscle, a major abductor of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, passes around the posterior aspect of the upper part of the humerus (the surgical neck).

The axillary nerve, which supplies the deltoid muscle, a major abductor of the humerus at the glenohumeral joint, passes around the posterior aspect of the upper part of the humerus (the surgical neck).

The radial nerve, which supplies all of the extensor muscles of the upper limb, passes diagonally around the posterior surface of the middle of the humerus in the radial groove.

The radial nerve, which supplies all of the extensor muscles of the upper limb, passes diagonally around the posterior surface of the middle of the humerus in the radial groove.

The ulnar nerve, which is ultimately destined for the hand, passes posteriorly to a bony protrusion, the medial epicondyle, on the medial side of the distal end of the humerus.

The ulnar nerve, which is ultimately destined for the hand, passes posteriorly to a bony protrusion, the medial epicondyle, on the medial side of the distal end of the humerus.

Fractures of the humerus in any one of these three regions can endanger the related nerve.

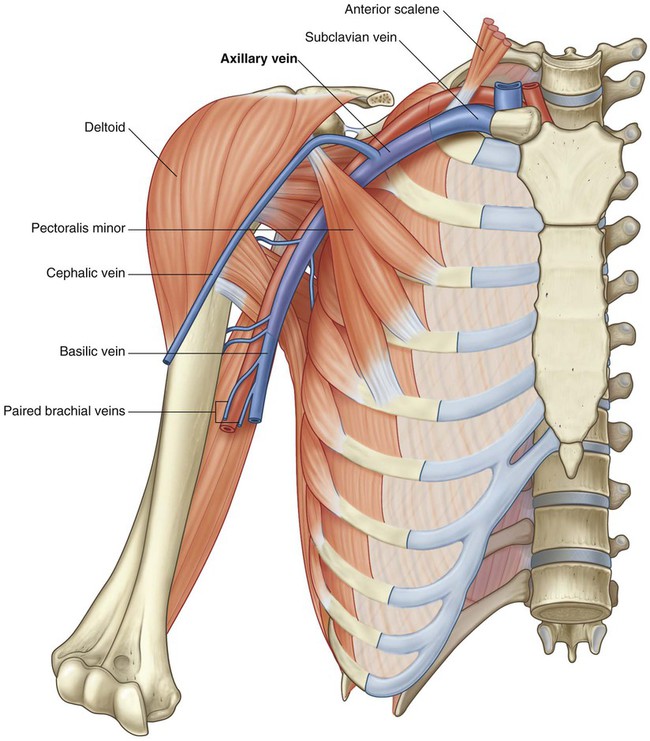

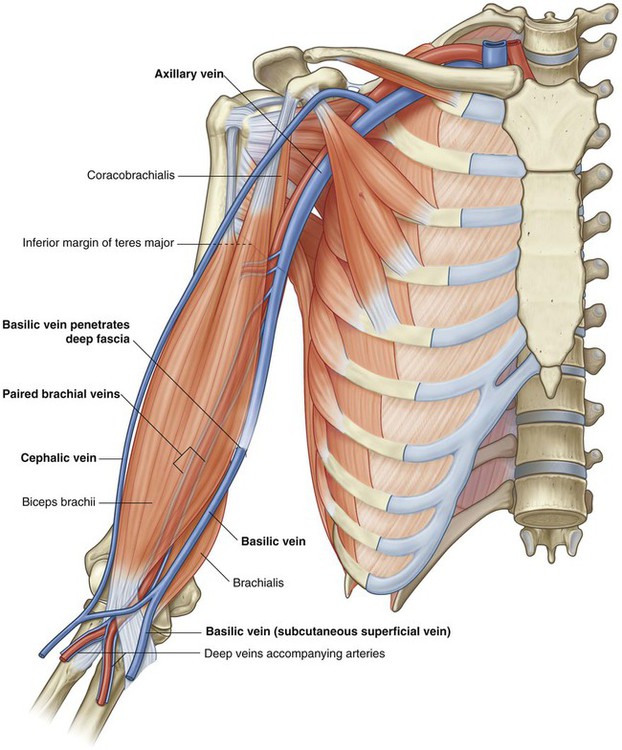

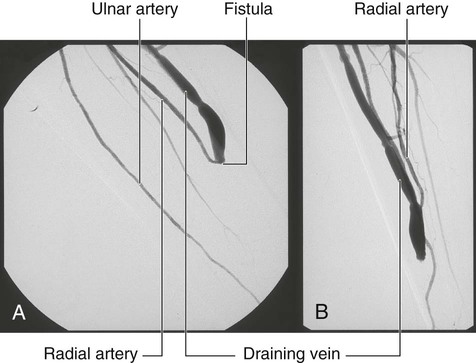

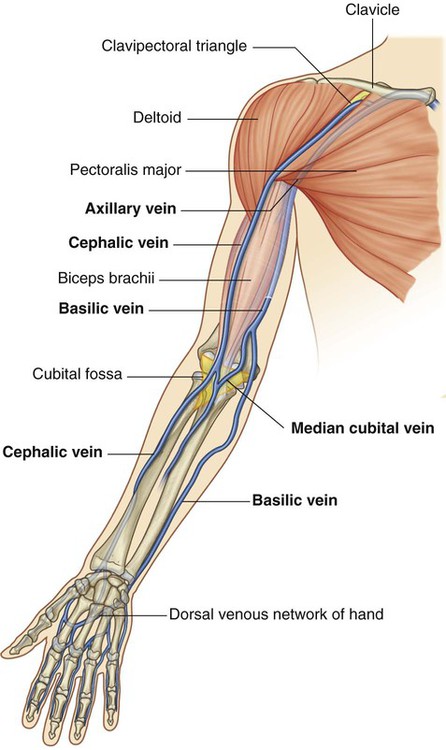

Superficial veins

Large veins embedded in the superficial fascia of the upper limb are often used to access a patient’s vascular system and to withdraw blood. The most significant of these veins are the cephalic, basilic, and median cubital veins (Fig. 7.18).

The cephalic and basilic veins originate from the dorsal venous network on the back of the hand.

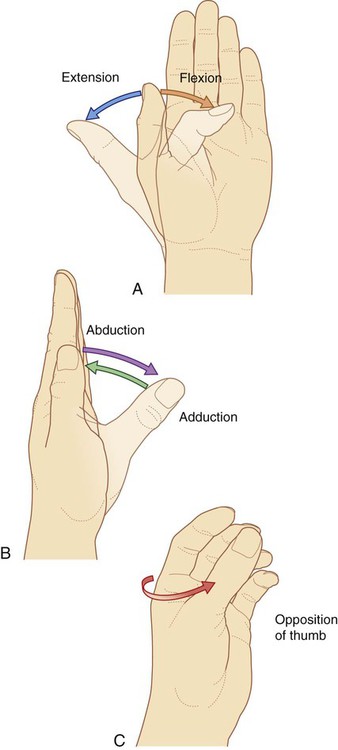

Orientation of the thumb

The thumb is positioned at right angles to the orientation of the index, middle, ring, and little fingers (Fig. 7.19). As a result, movements of the thumb occur at right angles to those of the other digits. For example, flexion brings the thumb across the palm, whereas abduction moves it away from the fingers at right angles to the palm.

Regional anatomy

Shoulder

The shoulder is the region of upper limb attachment to the trunk.

The bone framework of the shoulder consists of:

Bones

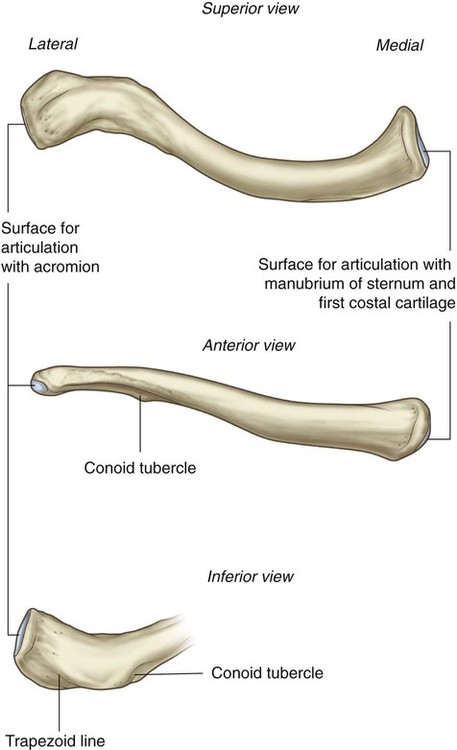

Clavicle

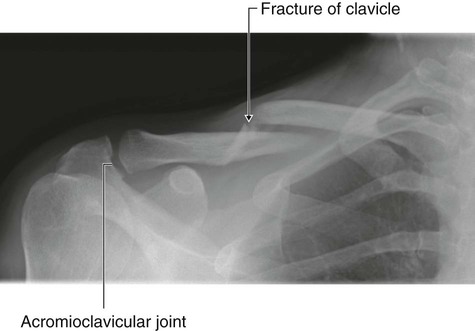

The clavicle is the only bony attachment between the trunk and the upper limb. It is palpable along its entire length and has a gentle S-shaped contour, with the forward-facing convex part medial and the forward-facing concave part lateral. The acromial (lateral) end of the clavicle is flat, whereas the sternal (medial) end is more robust and somewhat quadrangular in shape (Fig. 7.20).

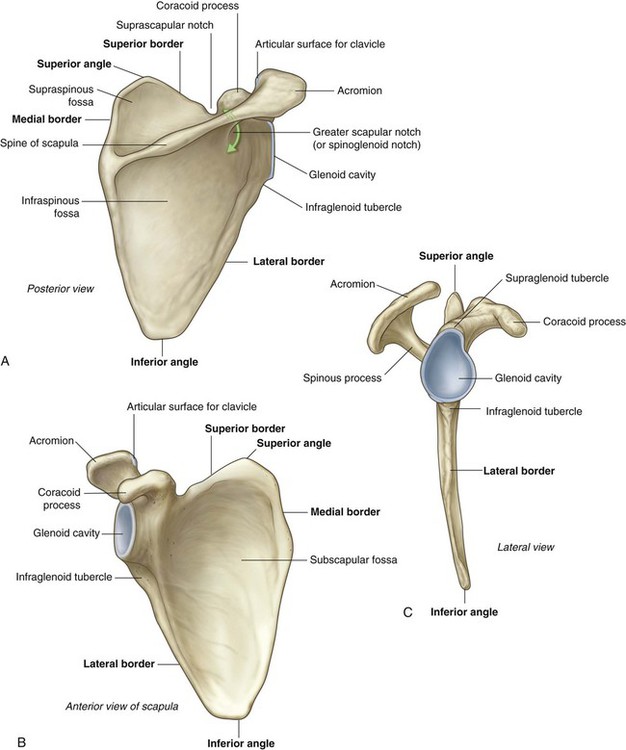

Scapula

The scapula is a large, flat triangular bone with:

three angles (lateral, superior, and inferior),

three angles (lateral, superior, and inferior),

three borders (superior, lateral, and medial),

three borders (superior, lateral, and medial),

two surfaces (costal and posterior), and

two surfaces (costal and posterior), and

three processes (acromion, spine, and coracoid process) (Fig. 7.21).

three processes (acromion, spine, and coracoid process) (Fig. 7.21).

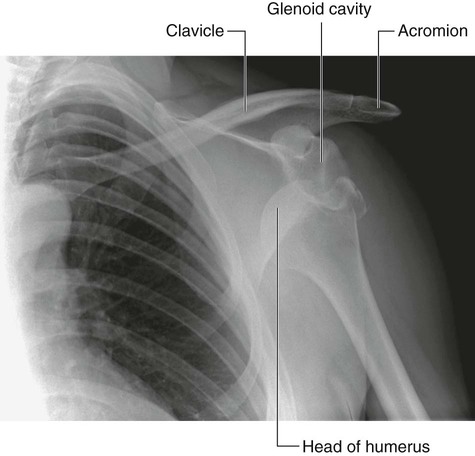

The lateral angle of the scapula is marked by a shallow, somewhat comma-shaped glenoid cavity, which articulates with the head of the humerus to form the glenohumeral joint (Fig. 7.21B,C).

A prominent spine subdivides the posterior surface of the scapula into a small, superior supraspinous fossa and a much larger, inferior infraspinous fossa (Fig. 7.21A).

Unlike the posterior surface, the costal surface of the scapula is unremarkable, being characterized by a shallow concave subscapular fossa over much of its extent (Fig. 7.21B). The costal surface and margins provide for muscle attachment, and the costal surface, together with its related muscle (subscapularis), moves freely over the underlying thoracic wall.

Proximal humerus

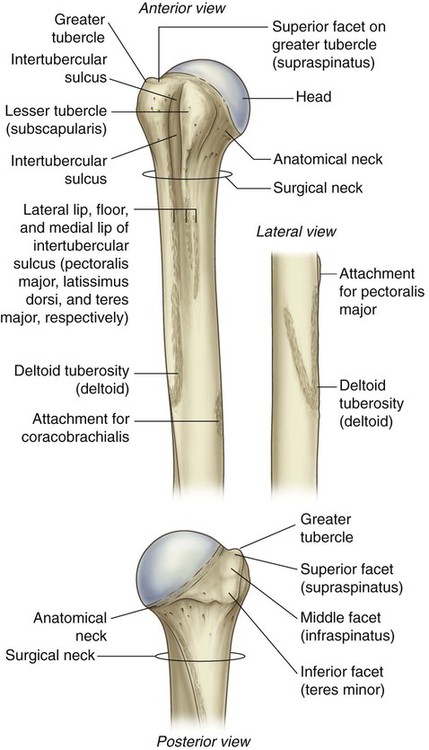

The proximal end of the humerus consists of the head, the anatomical neck, the greater and lesser tubercles, the surgical neck, and the superior half of the shaft of the humerus (Fig. 7.22).

Greater and lesser tubercles

The superior facet is for attachment of the supraspinatus muscle.

The superior facet is for attachment of the supraspinatus muscle.

A deep intertubercular sulcus (bicipital groove) separates the lesser and greater tubercles and continues inferiorly onto the proximal shaft of the humerus (Fig. 7.22). The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii passes through this sulcus.

The lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus is continuous inferiorly with a large V-shaped deltoid tuberosity on the lateral surface of the humerus midway along its length (Fig. 7.22), which is where the deltoid muscle inserts onto the humerus.

Surgical neck

One of the most important features of the proximal end of the humerus is the surgical neck (Fig. 7.22). This region is oriented in the horizontal plane between the expanded proximal part of the humerus (head, anatomical neck, and tubercles) and the narrower shaft. The axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery, which pass into the deltoid region from the axilla, do so immediately posterior to the surgical neck. Because the surgical neck is weaker than more proximal regions of the bone, it is one of the sites where the humerus commonly fractures. The associated nerve (axillary) and artery (posterior circumflex humeral) can be damaged by fractures in this region.

Joints

Sternoclavicular joint

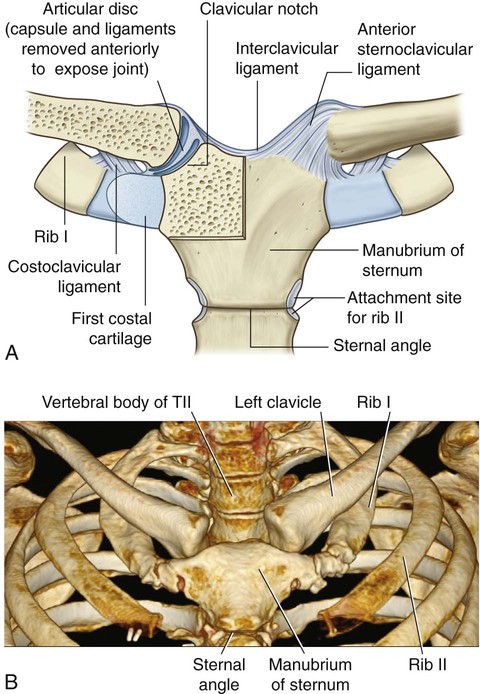

The sternoclavicular joint occurs between the proximal end of the clavicle and the clavicular notch of the manubrium of the sternum together with a small part of the first costal cartilage (Fig. 7.23). It is synovial and saddle shaped. The articular cavity is completely separated into two compartments by an articular disc. The sternoclavicular joint allows movement of the clavicle, predominantly in the anteroposterior and vertical planes, although some rotation also occurs.

The sternoclavicular joint is surrounded by a joint capsule and is reinforced by four ligaments:

The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments are anterior and posterior, respectively, to the joint.

The anterior and posterior sternoclavicular ligaments are anterior and posterior, respectively, to the joint.

An interclavicular ligament links the ends of the two clavicles to each other and to the superior surface of the manubrium of the sternum.

An interclavicular ligament links the ends of the two clavicles to each other and to the superior surface of the manubrium of the sternum.

The costoclavicular ligament is positioned laterally to the joint and links the proximal end of the clavicle to the first rib and related costal cartilage.

The costoclavicular ligament is positioned laterally to the joint and links the proximal end of the clavicle to the first rib and related costal cartilage.

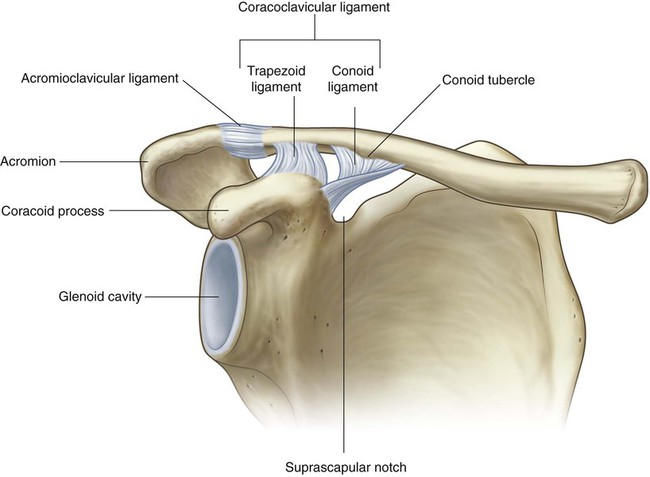

Acromioclavicular joint

The acromioclavicular joint is a small synovial joint between an oval facet on the medial surface of the acromion and a similar facet on the acromial end of the clavicle (Fig. 7.24, also see Fig. 7.31). It allows movement in the anteroposterior and vertical planes together with some axial rotation.

The acromioclavicular joint is surrounded by a joint capsule and is reinforced by:

a small acromioclavicular ligament superior to the joint and passing between adjacent regions of the clavicle and acromion, and

a small acromioclavicular ligament superior to the joint and passing between adjacent regions of the clavicle and acromion, and

a much larger coracoclavicular ligament, which is not directly related to the joint, but is an important strong accessory ligament, providing much of the weight-bearing support for the upper limb on the clavicle and maintaining the position of the clavicle on the acromion—it spans the distance between the coracoid process of the scapula and the inferior surface of the acromial end of the clavicle and comprises an anterior trapezoid ligament (which attaches to the trapezoid line on the clavicle) and a posterior conoid ligament (which attaches to the related conoid tubercle).

a much larger coracoclavicular ligament, which is not directly related to the joint, but is an important strong accessory ligament, providing much of the weight-bearing support for the upper limb on the clavicle and maintaining the position of the clavicle on the acromion—it spans the distance between the coracoid process of the scapula and the inferior surface of the acromial end of the clavicle and comprises an anterior trapezoid ligament (which attaches to the trapezoid line on the clavicle) and a posterior conoid ligament (which attaches to the related conoid tubercle).

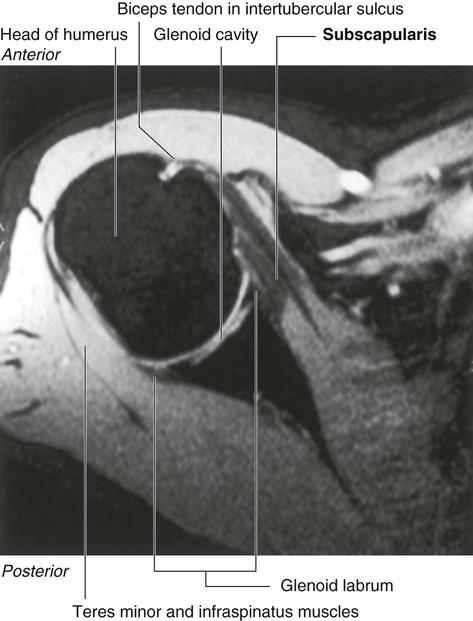

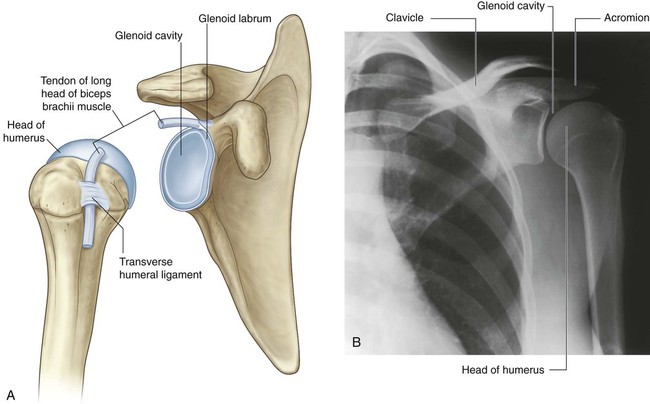

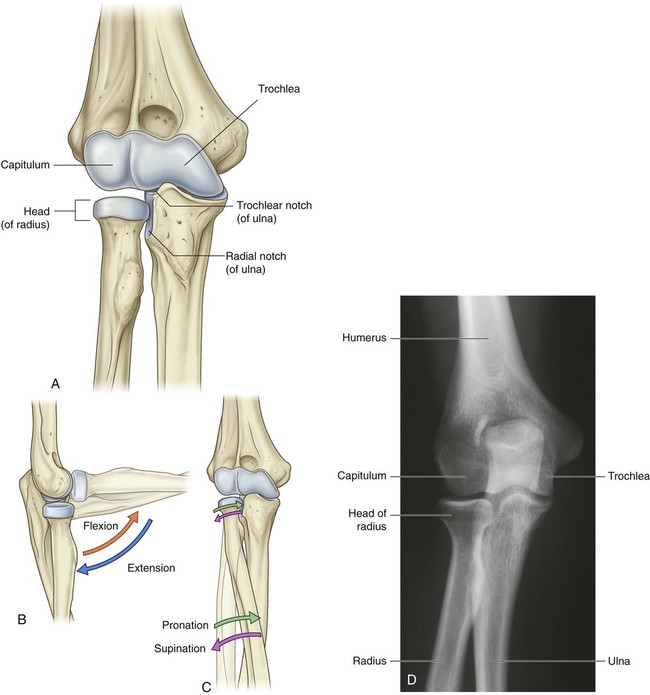

Glenohumeral joint

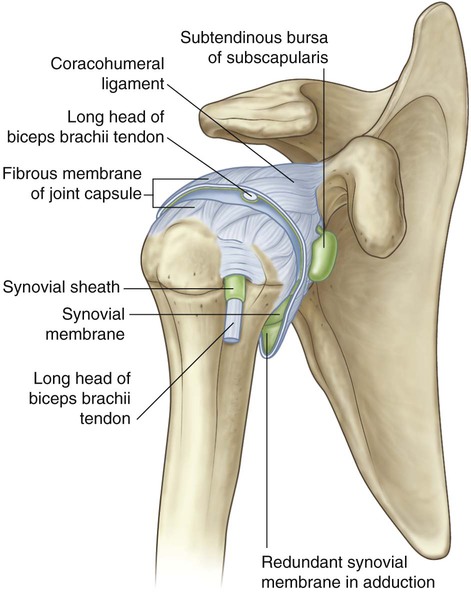

The glenohumeral joint is a synovial ball and socket articulation between the head of the humerus and the glenoid cavity of the scapula (Fig. 7.25). It is multiaxial with a wide range of movements provided at the cost of skeletal stability. Joint stability is provided, instead, by the rotator cuff muscles, the long head of the biceps brachii muscle, related bony processes, and extracapsular ligaments. Movements at the joint include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial rotation, lateral rotation, and circumduction.

The articular surfaces of the glenohumeral joint are the large spherical head of the humerus and the small glenoid cavity of the scapula (Fig. 7.25). Each of the surfaces is covered by hyaline cartilage.

The synovial membrane attaches to the margins of the articular surfaces and lines the fibrous membrane of the joint capsule (Fig. 7.26). The synovial membrane is loose inferiorly. This redundant region of synovial membrane and related fibrous membrane accommodates abduction of the arm.

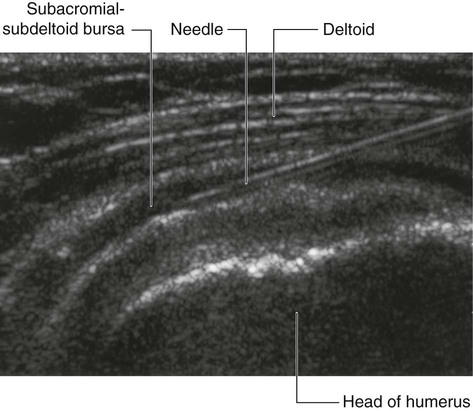

between the acromion (or deltoid muscle) and supraspinatus muscle (or joint capsule) (the subacromial or subdeltoid bursa),

between the acromion (or deltoid muscle) and supraspinatus muscle (or joint capsule) (the subacromial or subdeltoid bursa),

between the acromion and skin,

between the acromion and skin,

between the coracoid process and the joint capsule, and

between the coracoid process and the joint capsule, and

in relationship to tendons of muscles around the joint (coracobrachialis, teres major, long head of triceps brachii, and latissimus dorsi muscles).

in relationship to tendons of muscles around the joint (coracobrachialis, teres major, long head of triceps brachii, and latissimus dorsi muscles).

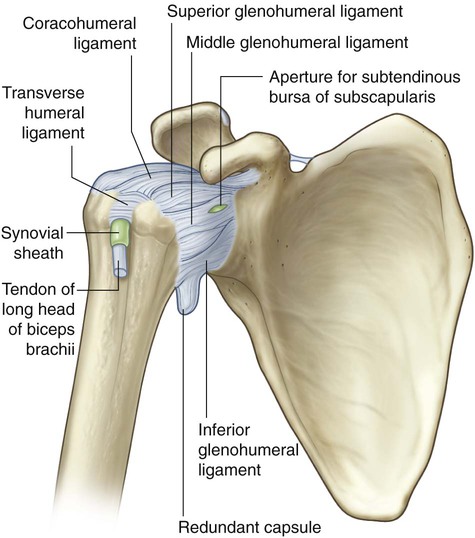

The fibrous membrane of the joint capsule attaches to the margin of the glenoid cavity, outside the attachment of the glenoid labrum and the long head of the biceps brachii muscle, and to the anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27).

The fibrous membrane of the joint capsule is thickened:

anterosuperiorly in three locations to form superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments, which pass from the superomedial margin of the glenoid cavity to the lesser tubercle and inferiorly related anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27);

anterosuperiorly in three locations to form superior, middle, and inferior glenohumeral ligaments, which pass from the superomedial margin of the glenoid cavity to the lesser tubercle and inferiorly related anatomical neck of the humerus (Fig. 7.27);

superiorly between the base of the coracoid process and the greater tubercle of the humerus (the coracohumeral ligament); and

superiorly between the base of the coracoid process and the greater tubercle of the humerus (the coracohumeral ligament); and

between the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus (transverse humeral ligament)—this holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle in the intertubercular sulcus (Fig. 7.27).

between the greater and lesser tubercles of the humerus (transverse humeral ligament)—this holds the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle in the intertubercular sulcus (Fig. 7.27).

Joint stability is provided by surrounding muscle tendons and a skeletal arch formed superiorly by the coracoid process and acromion and the coraco-acromial ligament (Fig. 7.28).

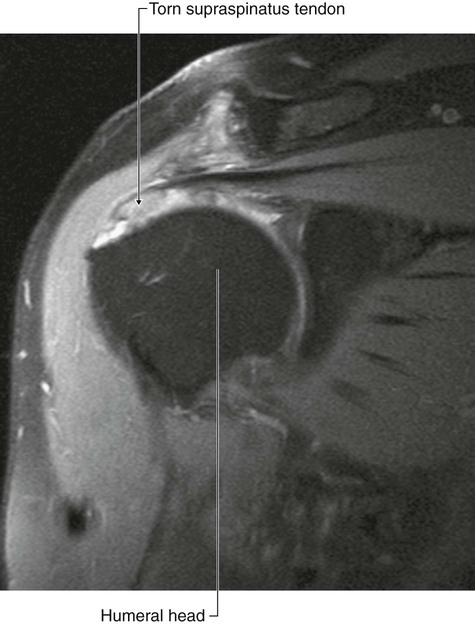

Tendons of the rotator cuff muscles (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis muscles) blend with the joint capsule and form a musculotendinous collar that surrounds the posterior, superior, and anterior aspects of the glenohumeral joint (Figs. 7.28 and 7.29). This cuff of muscles stabilizes and holds the head of the humerus in the glenoid cavity of the scapula without compromising the arm’s flexibility and range of motion. The tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii muscle passes superiorly through the joint and restricts upward movement of the humeral head on the glenoid cavity.

Muscles

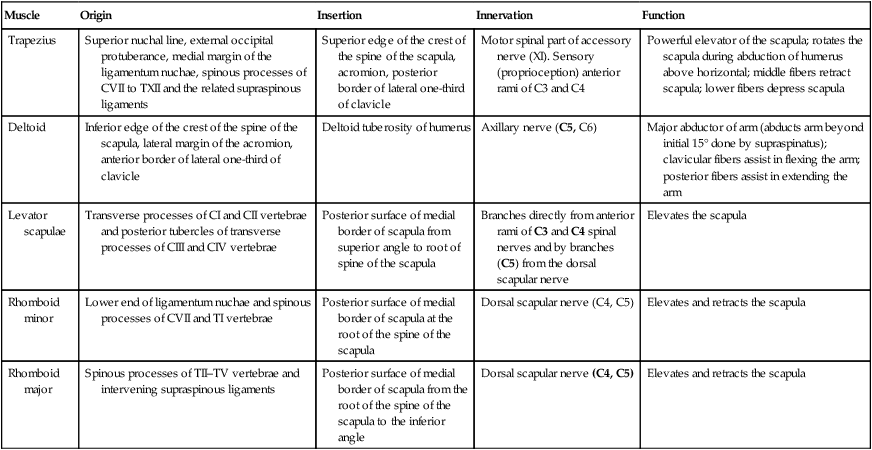

The two most superficial muscles of the shoulder are the trapezius and deltoid muscles (Fig. 7.35 and Table 7.1). Together, they provide the characteristic contour of the shoulder:

Table 7.1

Muscles of the shoulder (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Trapezius | Superior nuchal line, external occipital protuberance, medial margin of the ligamentum nuchae, spinous processes of CVII to TXII and the related supraspinous ligaments | Superior edge of the crest of the spine of the scapula, acromion, posterior border of lateral one-third of clavicle | Motor spinal part of accessory nerve (XI). Sensory (proprioception) anterior rami of C3 and C4 | Powerful elevator of the scapula; rotates the scapula during abduction of humerus above horizontal; middle fibers retract scapula; lower fibers depress scapula |

| Deltoid | Inferior edge of the crest of the spine of the scapula, lateral margin of the acromion, anterior border of lateral one-third of clavicle | Deltoid tuberosity of humerus | Axillary nerve (C5, C6) | Major abductor of arm (abducts arm beyond initial 15° done by supraspinatus); clavicular fibers assist in flexing the arm; posterior fibers assist in extending the arm |

| Levator scapulae | Transverse processes of CI and CII vertebrae and posterior tubercles of transverse processes of CIII and CIV vertebrae | Posterior surface of medial border of scapula from superior angle to root of spine of the scapula | Branches directly from anterior rami of C3 and C4 spinal nerves and by branches (C5) from the dorsal scapular nerve | Elevates the scapula |

| Rhomboid minor | Lower end of ligamentum nuchae and spinous processes of CVII and TI vertebrae | Posterior surface of medial border of scapula at the root of the spine of the scapula | Dorsal scapular nerve (C4, C5) | Elevates and retracts the scapula |

| Rhomboid major | Spinous processes of TII–TV vertebrae and intervening supraspinous ligaments | Posterior surface of medial border of scapula from the root of the spine of the scapula to the inferior angle | Dorsal scapular nerve (C4, C5) | Elevates and retracts the scapula |

The trapezius attaches the scapula and clavicle to the trunk.

The trapezius attaches the scapula and clavicle to the trunk.

The deltoid attaches the scapula and clavicle to the humerus.

The deltoid attaches the scapula and clavicle to the humerus.

Trapezius

The trapezius muscle has an extensive origin from the axial skeleton, which includes sites on the skull and the vertebrae, from CI to TXII (Fig. 7.36). From CI to CVII, the muscle attaches to the vertebrae through the ligamentum nuchae. The muscle inserts onto the skeletal framework of the shoulder along the inner margins of a continuous U-shaped line of attachment oriented in the horizontal plane, with the bottom of the U directed laterally. Together, the left and right trapezius muscles form a diamond or trapezoid shape, from which the name is derived.

Innervation of the trapezius muscle is by the accessory nerve [XI] and the anterior rami of cervical nerves C3 and C4 (Fig. 7.36). These nerves pass vertically along the deep surface of the muscle. The accessory nerve can be evaluated by testing the function of the trapezius muscle. This is most easily done by asking patients to shrug their shoulders against resistance.

Deltoid

The deltoid muscle is large and triangular in shape, with its base attached to the scapula and clavicle and its apex attached to the humerus (Fig. 7.36). It originates along a continuous U-shaped line of attachment to the clavicle and the scapula, mirroring the adjacent insertion sites of the trapezius muscle. It inserts into the deltoid tuberosity on the lateral surface of the shaft of the humerus.

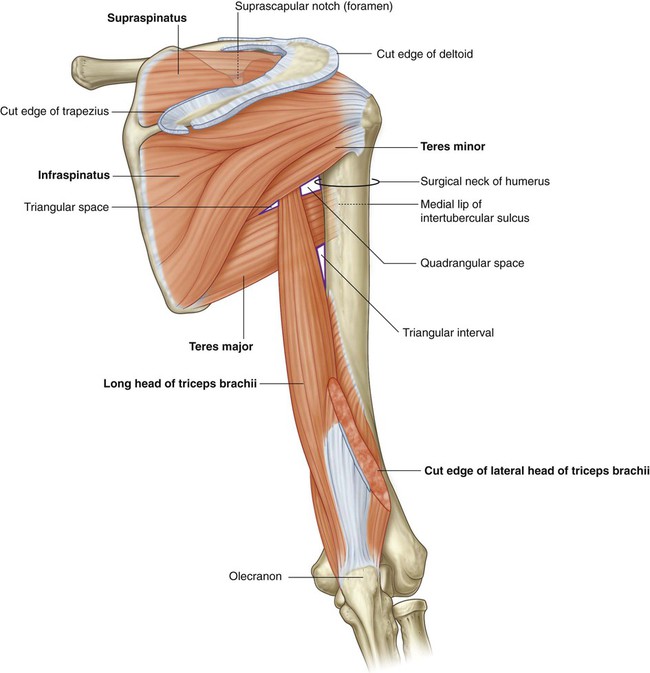

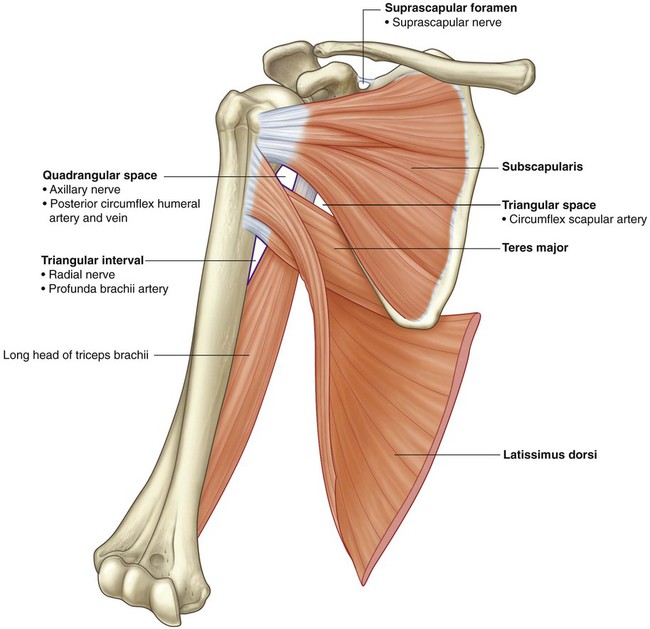

Posterior scapular region

The posterior scapular region occupies the posterior aspect of the scapula and is located deep to the trapezius and deltoid muscles (Fig. 7.37 and Table 7.2). It contains four muscles, which pass between the scapula and proximal end of the humerus: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and teres major muscles.

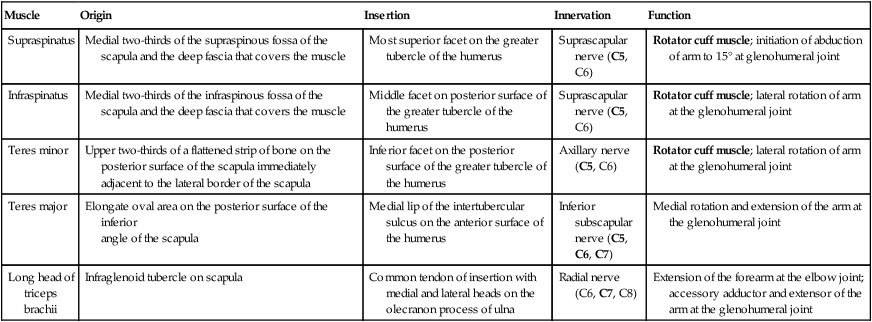

Table 7.2

Muscles of the posterior scapular region (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Supraspinatus | Medial two-thirds of the supraspinous fossa of the scapula and the deep fascia that covers the muscle | Most superior facet on the greater tubercle of the humerus | Suprascapular nerve (C5, C6) | Rotator cuff muscle; initiation of abduction of arm to 15° at glenohumeral joint |

| Infraspinatus | Medial two-thirds of the infraspinous fossa of the scapula and the deep fascia that covers the muscle | Middle facet on posterior surface of the greater tubercle of the humerus | Suprascapular nerve (C5, C6) | Rotator cuff muscle; lateral rotation of arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Teres minor | Upper two-thirds of a flattened strip of bone on the posterior surface of the scapula immediately adjacent to the lateral border of the scapula | Inferior facet on the posterior surface of the greater tubercle of the humerus | Axillary nerve (C5, C6) | Rotator cuff muscle; lateral rotation of arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Teres major | Elongate oval area on the posterior surface of the inferior angle of the scapula |

Medial lip of the intertubercular sulcus on the anterior surface of the humerus | Inferior subscapular nerve (C5, C6, C7) | Medial rotation and extension of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

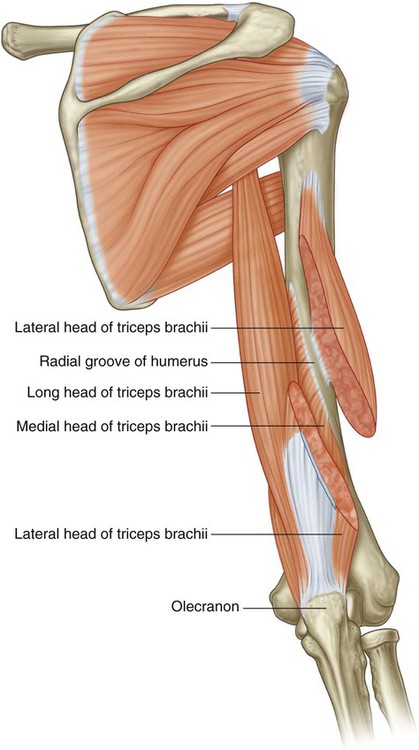

| Long head of triceps brachii | Infraglenoid tubercle on scapula | Common tendon of insertion with medial and lateral heads on the olecranon process of ulna | Radial nerve (C6, C7, C8) | Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint; accessory adductor and extensor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

Muscles

Supraspinatus and infraspinatus

The supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles originate from two large fossae, one above and one below the spine, on the posterior surface of the scapula (Fig. 7.37). They form tendons that insert on the greater tubercle of the humerus.

The tendon of the supraspinatus passes under the acromion, where it is separated from the bone by a subacromial bursa, passes over the glenohumeral joint, and inserts on the superior facet of the greater tubercle.

The tendon of the supraspinatus passes under the acromion, where it is separated from the bone by a subacromial bursa, passes over the glenohumeral joint, and inserts on the superior facet of the greater tubercle.

The tendon of the infraspinatus passes posteriorly to the glenohumeral joint and inserts on the middle facet of the greater tubercle.

The tendon of the infraspinatus passes posteriorly to the glenohumeral joint and inserts on the middle facet of the greater tubercle.

The supraspinatus initiates abduction of the arm. The infraspinatus laterally rotates the humerus.

Teres minor and teres major

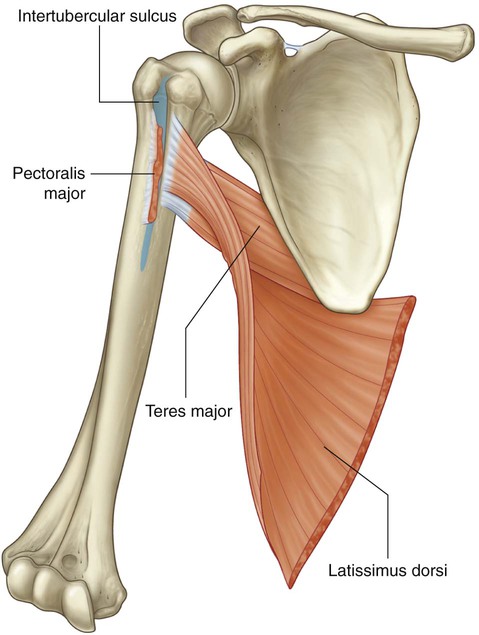

The teres minor muscle is a cord-like muscle that originates from a flattened area of the scapula immediately adjacent to its lateral border below the infraglenoid tubercle (Fig. 7.37). Its tendon inserts on the inferior facet of the greater tubercle of the humerus. The teres minor laterally rotates the humerus and is a component of the rotator cuff.

The teres major muscle originates from a large oval region on the posterior surface of the inferior angle of the scapula (Fig. 7.37). This broad cord-like muscle passes superiorly and laterally and ends as a flat tendon that attaches to the medial lip of the intertubercular sulcus on the anterior surface of the humerus. The teres major medially rotates and extends the humerus.

Gateways to the posterior scapular region

Suprascapular foramen

The suprascapular foramen is the route through which structures pass between the base of the neck and the posterior scapular region (Fig. 7.37). It is formed by the suprascapular notch of the scapula and the superior transverse scapular (suprascapular) ligament, which converts the notch into a foramen.

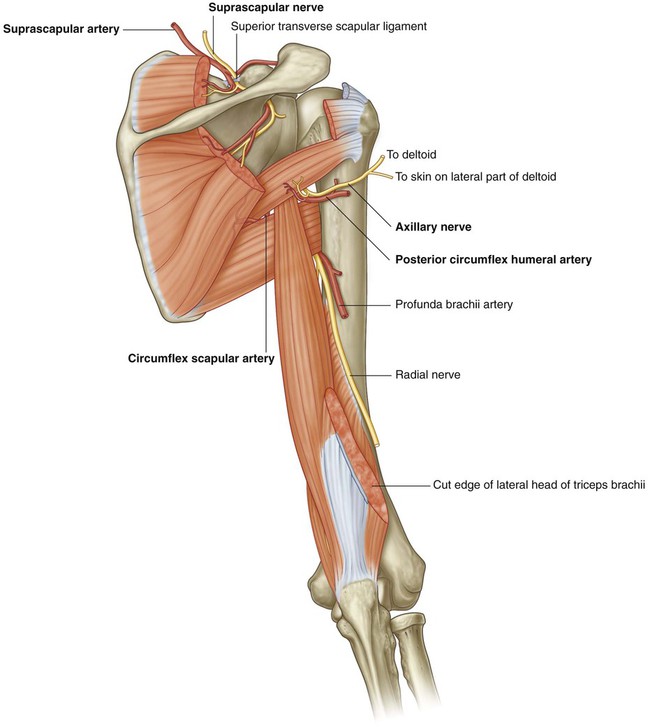

The suprascapular nerve passes through the suprascapular foramen; the suprascapular artery and the suprascapular vein follow the same course as the nerve, but normally pass immediately superior to the superior transverse scapular ligament and not through the foramen (Fig. 7.38).

Quadrangular space (from posterior)

The quadrangular space provides a passageway for nerves and vessels passing between more anterior regions (the axilla) and the posterior scapular region (Fig. 7.37). In the posterior scapular region, its boundaries are formed by:

the inferior margin of the teres minor,

the inferior margin of the teres minor,

the surgical neck of the humerus,

the surgical neck of the humerus,

The axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery and vein pass through this space (Fig. 7.38).

Triangular space

The triangular space is an area of communication between the axilla and the posterior scapular region (Fig. 7.37). When viewed from the posterior scapular region, the triangular space is formed by:

the medial margin of the long head of the triceps brachii,

the medial margin of the long head of the triceps brachii,

The circumflex scapular artery and vein pass through this gap (Fig. 7.38).

Triangular interval

The triangular interval is formed by:

Because this space is below the inferior margin of the teres major, which defines the inferior boundary of the axilla, the triangular interval serves as a passageway between the anterior and posterior compartments of the arm and between the posterior compartment of the arm and the axilla. The radial nerve, the profunda brachii artery (deep artery of arm), and associated veins pass through it (Fig. 7.38).

Nerves

The two major nerves of the posterior scapular region are the suprascapular and axillary nerves, both of which originate from the brachial plexus in the axilla (Fig. 7.38).

Suprascapular nerve

The suprascapular nerve originates in the base of the neck from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus. It passes posterolaterally from its origin, through the suprascapular foramen to reach the posterior scapular region, where it lies in the plane between bone and muscle (Fig. 7.38).

Generally, the suprascapular nerve has no cutaneous branches.

Axillary nerve

The axillary nerve originates from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus. It exits the axilla by passing through the quadrangular space in the posterior wall of the axilla, and enters the posterior scapular region (Fig. 7.38). Together with the posterior circumflex humeral artery and vein, it is directly related to the posterior surface of the surgical neck of the humerus.

Arteries and veins

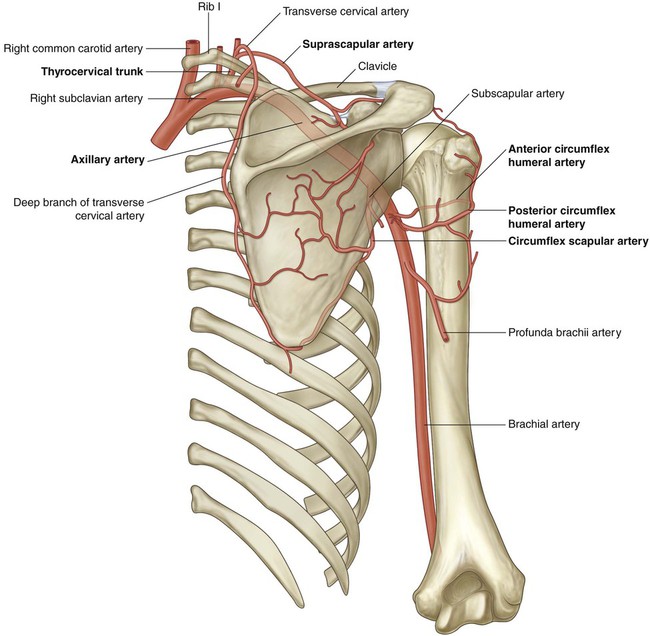

Three major arteries are found in the posterior scapular region: the suprascapular, posterior circumflex humeral, and circumflex scapular arteries. These arteries contribute to an interconnected vascular network around the scapula (Fig. 7.39).

Circumflex scapular artery

The circumflex scapular artery is a branch of the subscapular artery that also originates from the third part of the axillary artery in the axilla (Fig. 7.39). The circumflex scapular artery leaves the axilla through the triangular space and enters the posterior scapular region, passes through the origin of the teres minor muscle, and forms anastomotic connections with other arteries in the region.

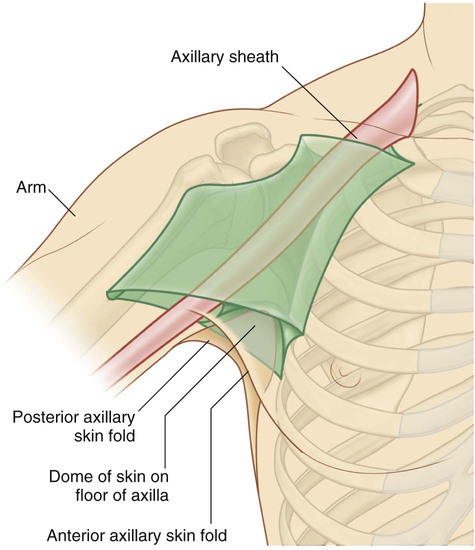

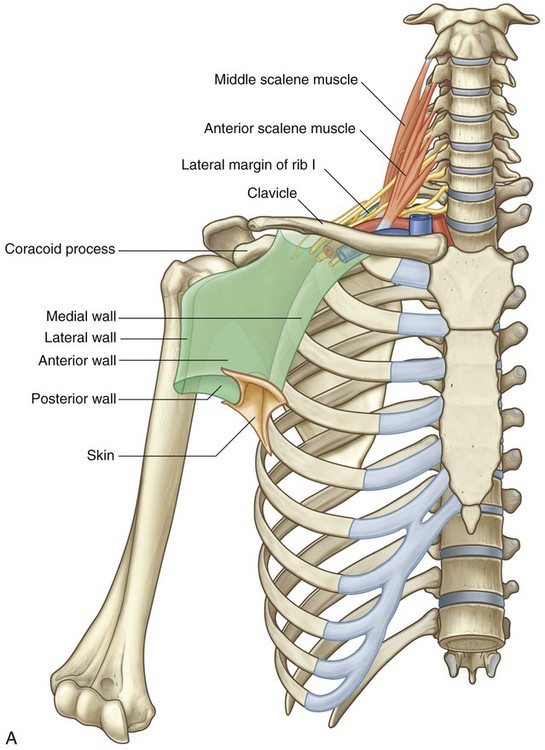

Axilla

The axilla is the gateway to the upper limb, providing an area of transition between the neck and the arm (Fig. 7.40A). Formed by the clavicle, the scapula, the upper thoracic wall, the humerus, and related muscles, the axilla is an irregularly shaped pyramidal space with:

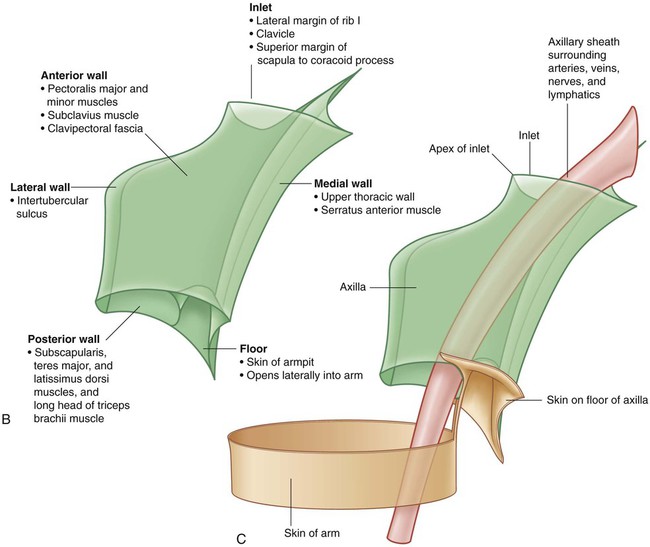

Axilla. B. Boundaries. C. Continuity with the arm.

All major structures passing into and out of the upper limb pass through the axilla (Fig. 7.40C). Apertures formed between muscles in the anterior and posterior walls enable structures to pass between the axilla and immediately adjacent regions (the posterior scapular, pectoral, and deltoid regions).

Axillary inlet

The axillary inlet is oriented in the horizontal plane and is somewhat triangular in shape, with its apex directed laterally (Fig. 7.40A,B). The margins of the inlet are completely formed by bone:

The medial margin is the lateral border of rib I.

The medial margin is the lateral border of rib I.

The anterior margin is the posterior surface of the clavicle.

The anterior margin is the posterior surface of the clavicle.

The posterior margin is the superior border of the scapula up to the coracoid process.

The posterior margin is the superior border of the scapula up to the coracoid process.

Major vessels and nerves pass between the neck and the axilla by crossing over the lateral border of rib I and through the axillary inlet (Fig. 7.40A).

The inferior trunk (lower trunk) of the brachial plexus lies directly on rib I in the neck, as does the subclavian artery and vein. As they pass over rib I, the vein and artery are separated by the insertion of the anterior scalene muscle (Fig. 7.40A).

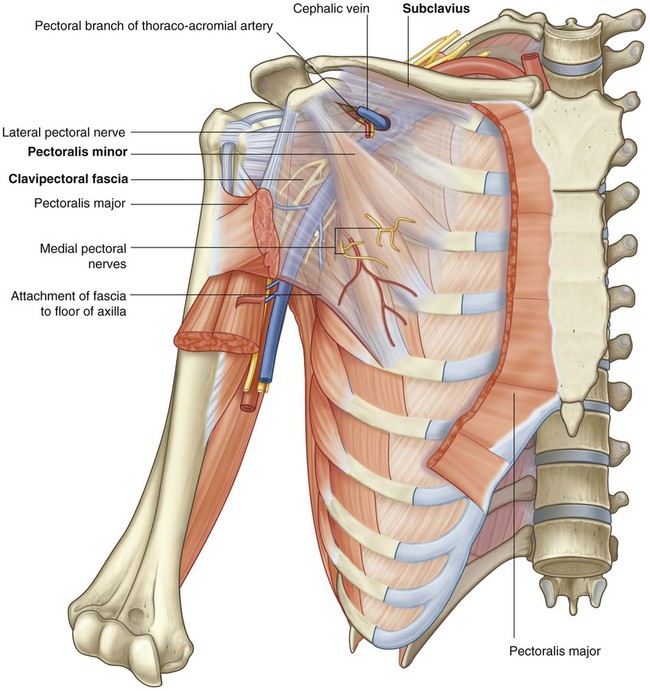

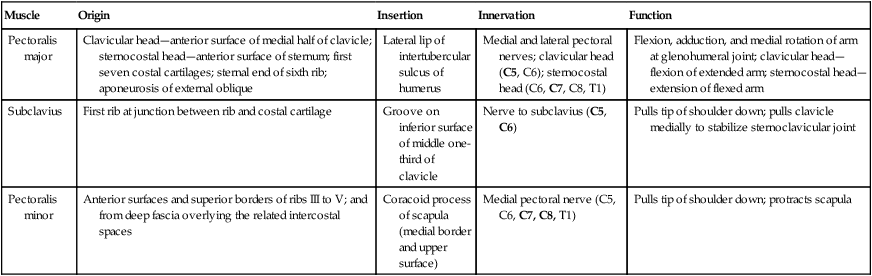

Anterior wall

The anterior wall of the axilla is formed by the lateral part of the pectoralis major muscle, the underlying pectoralis minor and subclavius muscles, and the clavipectoral fascia (Table 7.3).

Table 7.3

Muscles of the anterior wall of the axilla (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Pectoralis major | Clavicular head—anterior surface of medial half of clavicle; sternocostal head—anterior surface of sternum; first seven costal cartilages; sternal end of sixth rib; aponeurosis of external oblique | Lateral lip of intertubercular sulcus of humerus | Medial and lateral pectoral nerves; clavicular head (C5, C6); sternocostal head (C6, C7, C8, T1) | Flexion, adduction, and medial rotation of arm at glenohumeral joint; clavicular head—flexion of extended arm; sternocostal head—extension of flexed arm |

| Subclavius | First rib at junction between rib and costal cartilage | Groove on inferior surface of middle one-third of clavicle | Nerve to subclavius (C5, C6) | Pulls tip of shoulder down; pulls clavicle medially to stabilize sternoclavicular joint |

| Pectoralis minor | Anterior surfaces and superior borders of ribs III to V; and from deep fascia overlying the related intercostal spaces | Coracoid process of scapula (medial border and upper surface) | Medial pectoral nerve (C5, C6, C7, C8, T1) | Pulls tip of shoulder down; protracts scapula |

Pectoralis major

The pectoralis major muscle is the largest and most superficial muscle of the anterior wall (Fig. 7.41). Its inferior margin underlies the anterior axillary fold, which marks the anteroinferior border of the axilla. The muscle has two heads:

The clavicular head originates from the medial half of the clavicle.

The clavicular head originates from the medial half of the clavicle.

The sternocostal head originates from the medial part of the anterior thoracic wall—often, fibers from this head continue inferiorly and medially to attach to the anterior abdominal wall, forming an additional abdominal part of the muscle.

The sternocostal head originates from the medial part of the anterior thoracic wall—often, fibers from this head continue inferiorly and medially to attach to the anterior abdominal wall, forming an additional abdominal part of the muscle.

Subclavius

The subclavius muscle is a small muscle that lies deep to the pectoralis major muscle and passes between the clavicle and rib I (Fig. 7.42). It originates medially, as a tendon, from rib I at the junction between the rib and its costal cartilage. It passes laterally and superiorly to insert via a muscular attachment into an elongate shallow groove on the inferior surface of the middle third of the clavicle.

Pectoralis minor

The pectoralis minor muscle is a small triangular-shaped muscle that lies deep to the pectoralis major muscle and passes from the thoracic wall to the coracoid process of the scapula (Fig. 7.42). It originates as three muscular slips from the anterior surfaces and upper margins of ribs III to V and from the fascia overlying muscles of the related intercostal spaces. The muscle fibers pass superiorly and laterally to insert into the medial and upper aspects of the coracoid process.

Medial wall

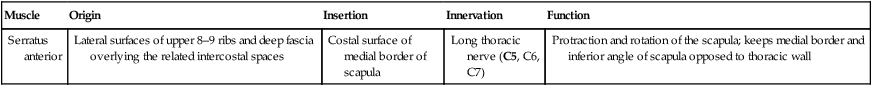

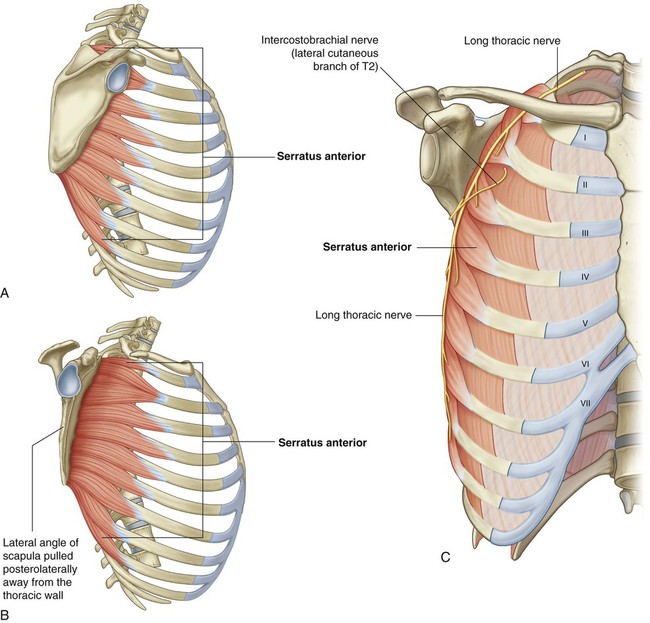

The medial wall of the axilla consists of the upper thoracic wall (the ribs and related intercostal tissues) and the serratus anterior muscle (Fig. 7.43 and Table 7.4, and see Fig. 7.40).

Table 7.4

Muscle of the medial wall of the axilla (spinal segment in bold is the major segment innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Serratus anterior | Lateral surfaces of upper 8–9 ribs and deep fascia overlying the related intercostal spaces | Costal surface of medial border of scapula | Long thoracic nerve (C5, C6, C7) | Protraction and rotation of the scapula; keeps medial border and inferior angle of scapula opposed to thoracic wall |

Serratus anterior

The serratus anterior muscle originates as a number of muscular slips from the lateral surfaces of ribs I to IX and the intervening deep fascia overlying the related intercostal spaces (Fig. 7.43). The muscle forms a flattened sheet, which passes posteriorly around the thoracic wall to insert primarily on the costal surface of the medial border of the scapula.

Intercostobrachial nerve

The only major structure that passes directly through the medial wall and into the axilla is the intercostobrachial nerve (Fig. 7.43). This nerve is the lateral cutaneous branch of the second intercostal nerve (anterior ramus of T2). It communicates with a branch of the brachial plexus (the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm) in the axilla and supplies skin on the upper posteromedial side of the arm, which is part of the T2 dermatome.

Lateral wall

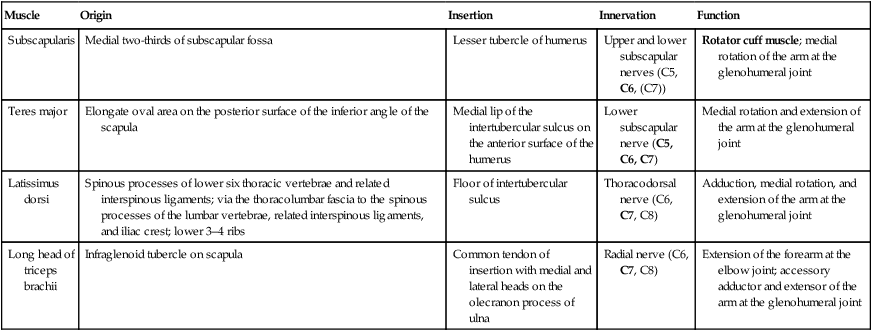

The lateral wall of the axilla is narrow and formed entirely by the intertubercular sulcus of the humerus (Fig. 7.44). The pectoralis major muscle of the anterior wall attaches to the lateral lip of the intertubercular sulcus. The latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles of the posterior wall attach to the floor and medial lip of the intertubercular sulcus, respectively (Table 7.5).

Table 7.5

Muscles of the lateral and posterior wall of the axilla (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle; spinal segments in parentheses do not consistently innervate the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Subscapularis | Medial two-thirds of subscapular fossa | Lesser tubercle of humerus | Upper and lower subscapular nerves (C5, C6, (C7)) | Rotator cuff muscle; medial rotation of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Teres major | Elongate oval area on the posterior surface of the inferior angle of the scapula | Medial lip of the intertubercular sulcus on the anterior surface of the humerus | Lower subscapular nerve (C5, C6, C7) | Medial rotation and extension of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Latissimus dorsi | Spinous processes of lower six thoracic vertebrae and related interspinous ligaments; via the thoracolumbar fascia to the spinous processes of the lumbar vertebrae, related interspinous ligaments, and iliac crest; lower 3–4 ribs | Floor of intertubercular sulcus | Thoracodorsal nerve (C6, C7, C8) | Adduction, medial rotation, and extension of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Long head of triceps brachii | Infraglenoid tubercle on scapula | Common tendon of insertion with medial and lateral heads on the olecranon process of ulna | Radial nerve (C6, C7, C8) | Extension of the forearm at the elbow joint; accessory adductor and extensor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

Posterior wall

The posterior wall of the axilla is complex (Fig. 7.45 and see Fig. 7.50). Its bone framework is formed by the costal surface of the scapula. Muscles of the wall are:

the subscapularis muscle (associated with the costal surface of the scapula),

the subscapularis muscle (associated with the costal surface of the scapula),

the distal parts of the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles (which pass into the wall from the back and posterior scapular region), and

the distal parts of the latissimus dorsi and teres major muscles (which pass into the wall from the back and posterior scapular region), and

the proximal part of the long head of the triceps brachii muscle (which passes vertically down the wall and into the arm).

the proximal part of the long head of the triceps brachii muscle (which passes vertically down the wall and into the arm).

Subscapularis

The subscapularis muscle forms the largest component of the posterior wall of the axilla. It originates from, and fills, the subscapular fossa and inserts on the lesser tubercle of the humerus (Figs. 7.45 and 7.46). The tendon crosses immediately anterior to the joint capsule of the glenohumeral joint.

Teres major and latissimus dorsi

The inferolateral aspect of the posterior wall of the axilla is formed by the terminal part of the teres major muscle and the tendon of the latissimus dorsi muscle (Fig. 7.45). These two structures lie under the posterior axillary fold, which marks the posteroinferior border of the axilla.

Gateways in the posterior wall

(See also “Gateways to the posterior scapular region,” pp. 717–721, and Figs. 7.37 and 7.38)

Quadrangular space

The quadrangular space provides a passageway for nerves and vessels passing between the axilla and the more posterior scapular and deltoid regions (Fig. 7.45). When viewed from anteriorly, its boundaries are formed by:

Triangular space

The triangular space is an area of communication between the axilla and the posterior scapular region (Fig. 7.45). When viewed from anteriorly, it is formed by:

the medial margin of the long head of the triceps brachii muscle,

the medial margin of the long head of the triceps brachii muscle,

The circumflex scapular artery and vein pass into this space.

Floor

The floor of the axilla is formed by fascia and a dome of skin that spans the distance between the inferior margins of the walls (Fig. 7.47 and see Fig. 7.40B). It is supported by the clavipectoral fascia. On a patient, the anterior axillary fold is more superior in position than is the posterior axillary fold.

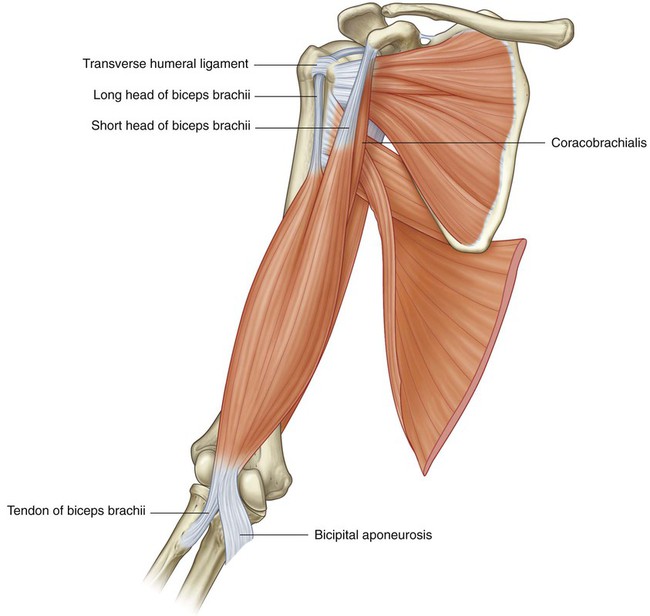

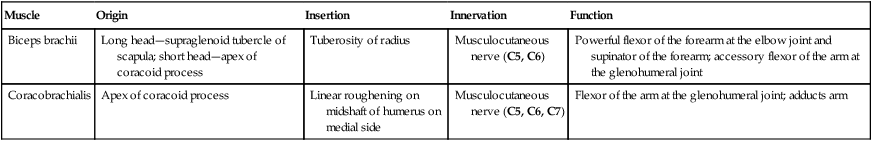

Contents of the axilla

The proximal parts of the biceps brachii and coracobrachialis muscles pass through the axilla (Table 7.6).

Table 7.6

Muscles having parts that pass through the axilla (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Biceps brachii | Long head—supraglenoid tubercle of scapula; short head—apex of coracoid process | Tuberosity of radius | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6) | Powerful flexor of the forearm at the elbow joint and supinator of the forearm; accessory flexor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Coracobrachialis | Apex of coracoid process | Linear roughening on midshaft of humerus on medial side | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7) | Flexor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint; adducts arm |

Biceps brachii

The biceps brachii muscle originates as two heads (Fig. 7.48):

The short head originates from the apex of the coracoid process of the scapula and passes vertically through the axilla and into the arm where it joins the long head.

The short head originates from the apex of the coracoid process of the scapula and passes vertically through the axilla and into the arm where it joins the long head.

The long head originates as a tendon from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, passes over the head of the humerus deep to the joint capsule of the glenohumeral joint, and enters the intertubercular sulcus where it is held in position by a ligament, the transverse humeral ligament, which spans the distance between the greater and lesser tubercles; the tendon passes through the axilla in the intertubercular sulcus and forms a muscle belly in the proximal part of the arm.

The long head originates as a tendon from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula, passes over the head of the humerus deep to the joint capsule of the glenohumeral joint, and enters the intertubercular sulcus where it is held in position by a ligament, the transverse humeral ligament, which spans the distance between the greater and lesser tubercles; the tendon passes through the axilla in the intertubercular sulcus and forms a muscle belly in the proximal part of the arm.

The biceps brachii muscle is innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

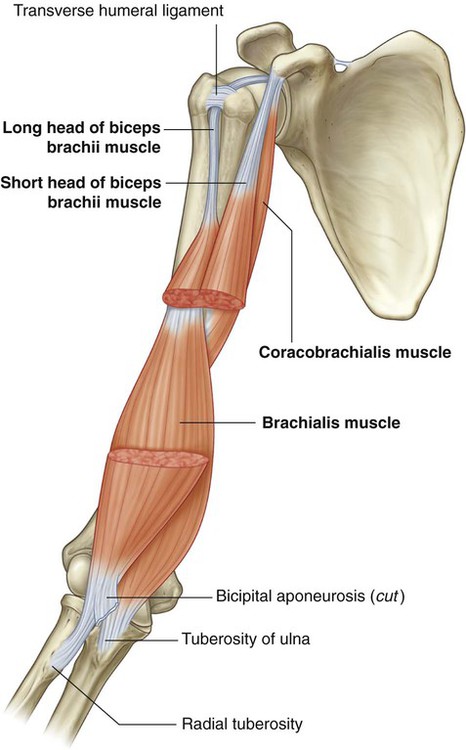

Coracobrachialis

The coracobrachialis muscle, together with the short head of the biceps brachii muscle, originates from the apex of the coracoid process (Fig. 7.48). It passes vertically through the axilla to insert on a small linear roughening on the medial aspect of the humerus, approximately midshaft.

The coracobrachialis muscle flexes the arm at the glenohumeral joint.

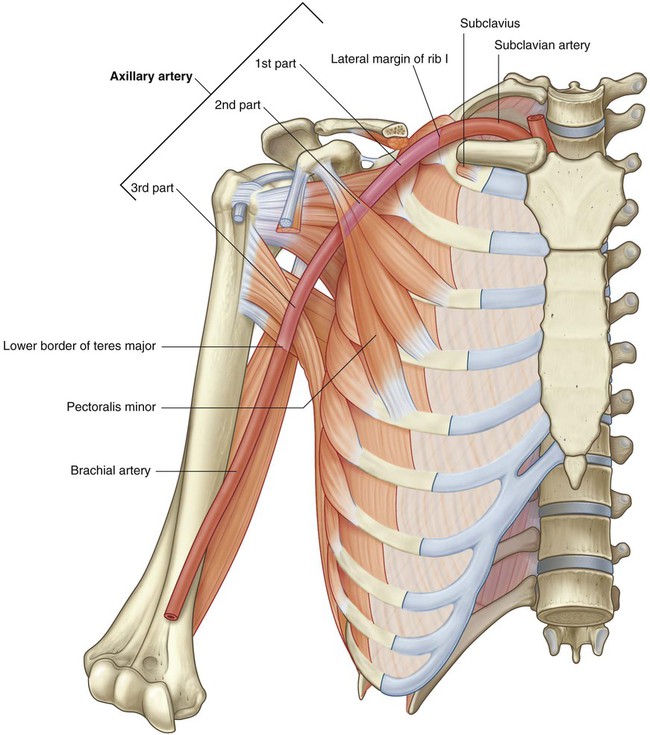

Axillary artery

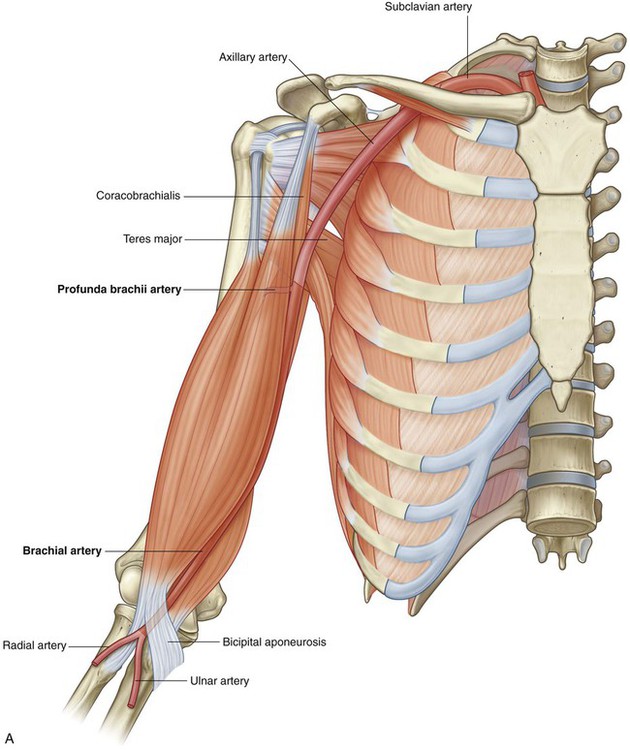

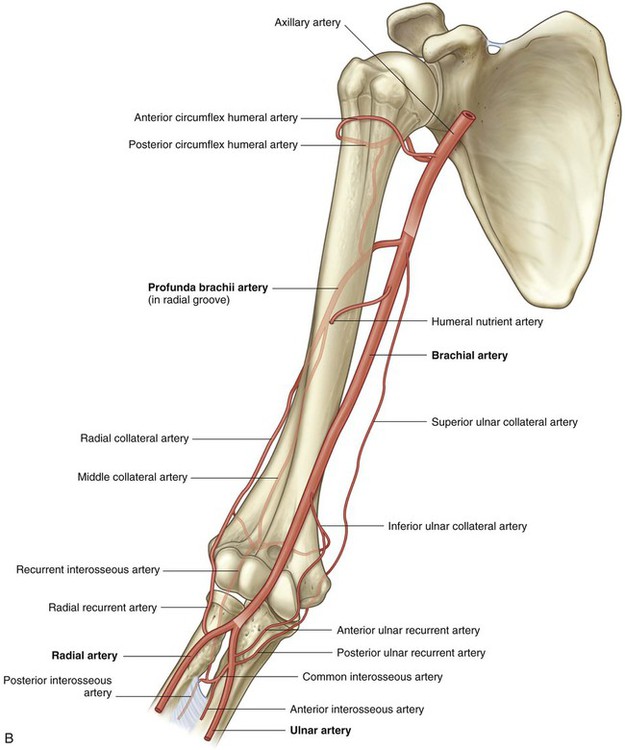

The axillary artery supplies the walls of the axilla and related regions, and continues as the major blood supply to the more distal parts of the upper limb (Fig. 7.49).

The axillary artery is separated into three parts by the pectoralis minor muscle, which crosses anteriorly to the vessel (Fig. 7.49):

The first part is proximal to the pectoralis minor.

The first part is proximal to the pectoralis minor.

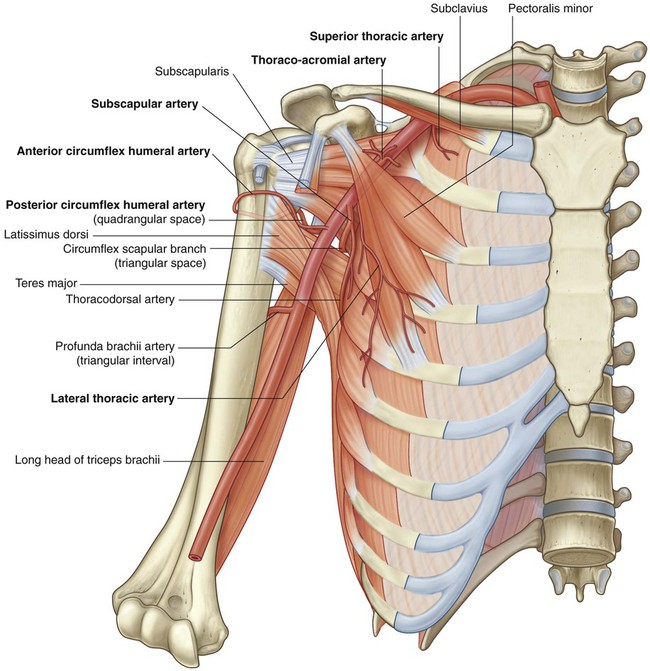

Generally, six branches arise from the axillary artery:

One branch, the superior thoracic artery, originates from the first part.

One branch, the superior thoracic artery, originates from the first part.

Two branches, the thoraco-acromial artery and the lateral thoracic artery, originate from the second part.

Two branches, the thoraco-acromial artery and the lateral thoracic artery, originate from the second part.

Three branches, the subscapular artery, the anterior circumflex humeral artery, and the posterior circumflex humeral artery, originate from the third part (Fig. 7.50).

Three branches, the subscapular artery, the anterior circumflex humeral artery, and the posterior circumflex humeral artery, originate from the third part (Fig. 7.50).

Thoraco-acromial artery

The thoraco-acromial artery is short and originates from the anterior surface of the second part of the axillary artery just posterior to the medial (superior) margin of the pectoralis minor muscle (Fig. 7.50). It curves around the superior margin of the muscle, penetrates the clavipectoral fascia, and immediately divides into four branches—the pectoral, deltoid, clavicular, and acromial branches, which supply the anterior axillary wall and related regions.

Additionally, the pectoral branch contributes vascular supply to the breast, and the deltoid branch passes into the clavipectoral triangle where it accompanies the cephalic vein and supplies adjacent structures (see Fig. 7.41).

Lateral thoracic artery

The lateral thoracic artery arises from the anterior surface of the second part of the axillary artery posterior to the lateral (inferior) margin of the pectoralis minor (Fig. 7.50). It follows the margin of the muscle to the thoracic wall and supplies the medial and anterior walls of the axilla. In women, branches emerge from around the inferior margin of the pectoralis major muscle and contribute to the vascular supply of the breast.

Subscapular artery

The subscapular artery is the largest branch of the axillary artery and is the major blood supply to the posterior wall of the axilla (Fig. 7.50). It also contributes to the blood supply of the posterior scapular region.

The circumflex scapular artery passes through the triangular space between the subscapularis, teres major, and long head of the triceps muscle. Posteriorly, it passes inferior to, or pierces, the origin of the teres minor muscle to enter the infraspinous fossa. It anastomoses with the suprascapular artery and the deep branch (dorsal scapular artery) of the transverse cervical artery, thereby contributing to an anastomotic network of vessels around the scapula.

The circumflex scapular artery passes through the triangular space between the subscapularis, teres major, and long head of the triceps muscle. Posteriorly, it passes inferior to, or pierces, the origin of the teres minor muscle to enter the infraspinous fossa. It anastomoses with the suprascapular artery and the deep branch (dorsal scapular artery) of the transverse cervical artery, thereby contributing to an anastomotic network of vessels around the scapula.

The thoracodorsal artery approximately follows the lateral border of the scapula to the inferior angle. It contributes to the vascular supply of the posterior and medial walls of the axilla.

The thoracodorsal artery approximately follows the lateral border of the scapula to the inferior angle. It contributes to the vascular supply of the posterior and medial walls of the axilla.

Anterior circumflex humeral artery

The anterior circumflex humeral artery is small compared to the posterior circumflex humeral artery, and originates from the lateral side of the third part of the axillary artery (Fig. 7.50). It passes anterior to the surgical neck of the humerus and anastomoses with the posterior circumflex humeral artery.

Posterior circumflex humeral artery

The posterior circumflex humeral artery originates from the lateral surface of the third part of the axillary artery immediately posterior to the origin of the anterior circumflex humeral artery (Fig. 7.50). With the axillary nerve, it leaves the axilla by passing through the quadrangular space between the teres major, teres minor, and long head of the triceps brachii muscle and the surgical neck of the humerus.

Brachial plexus

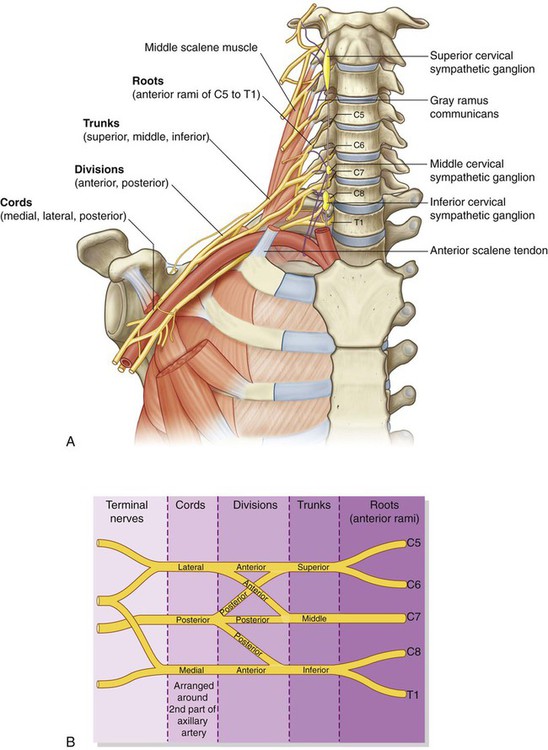

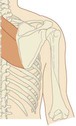

The brachial plexus is a somatic plexus formed by the anterior rami of C5 to C8, and most of the anterior ramus of T1 (Fig. 7.52). The plexus originates in the neck, passes laterally and inferiorly over rib I, and enters the axilla.

Roots

The roots of the brachial plexus are the anterior rami of C5 to C8, and most of T1. Close to their origin, the roots receive gray rami communicantes from the sympathetic trunk (Fig. 7.52). These carry postganglionic sympathetic fibers onto the roots for distribution to the periphery. The roots and trunks enter the posterior triangle of the neck by passing between the anterior scalene and middle scalene muscles and lie superior and posterior to the subclavian artery.

Trunks

The three trunks of the brachial plexus originate from the roots, pass laterally over rib I, and enter the axilla (Fig. 7.52):

Divisions

Each of the three trunks of the brachial plexus divides into an anterior and a posterior division (Fig. 7.52):

The three anterior divisions form parts of the brachial plexus that ultimately give rise to peripheral nerves associated with the anterior compartments of the arm and forearm.

The three anterior divisions form parts of the brachial plexus that ultimately give rise to peripheral nerves associated with the anterior compartments of the arm and forearm.

The three posterior divisions combine to form parts of the brachial plexus that give rise to nerves associated with the posterior compartments.

The three posterior divisions combine to form parts of the brachial plexus that give rise to nerves associated with the posterior compartments.

No peripheral nerves originate directly from the divisions of the brachial plexus.

Cords

The three cords of the brachial plexus originate from the divisions and are related to the second part of the axillary artery (Fig. 7.52):

The lateral cord results from the union of the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks and therefore has contributions from C5 to C7—it is positioned lateral to the second part of the axillary artery.

The lateral cord results from the union of the anterior divisions of the upper and middle trunks and therefore has contributions from C5 to C7—it is positioned lateral to the second part of the axillary artery.

The medial cord is medial to the second part of the axillary artery and is the continuation of the anterior division of the inferior trunk—it contains contributions from C8 and T1.

The medial cord is medial to the second part of the axillary artery and is the continuation of the anterior division of the inferior trunk—it contains contributions from C8 and T1.

The posterior cord occurs posterior to the second part of the axillary artery and originates as the union of all three posterior divisions—it contains contributions from all roots of the brachial plexus (C5 to T1).

The posterior cord occurs posterior to the second part of the axillary artery and originates as the union of all three posterior divisions—it contains contributions from all roots of the brachial plexus (C5 to T1).

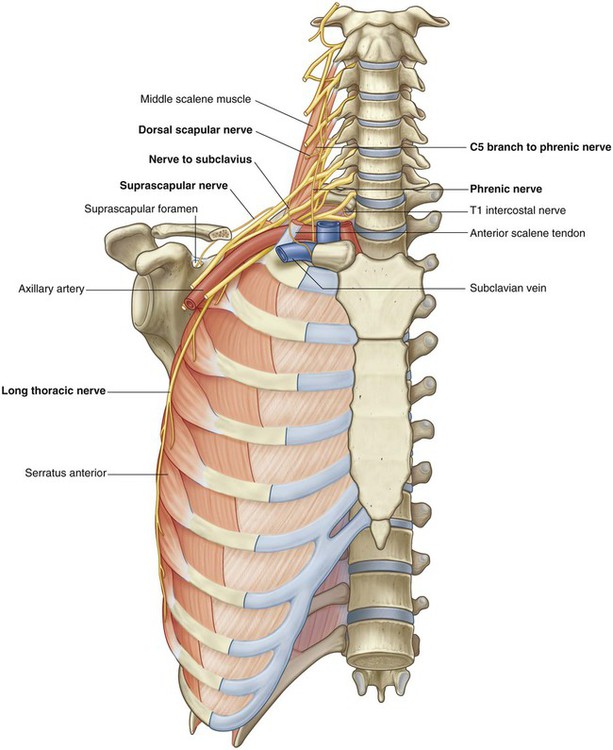

Branches (Table 7.7)

In addition to small segmental branches from C5 to C8 to muscles of the neck and a contribution of C5 to the phrenic nerve, the roots of the brachial plexus give rise to the dorsal scapular and long thoracic nerves (Fig. 7.53).

Table 7.7

Branches of brachial plexus (parentheses indicate that a spinal segment is a minor component of the nerve or is inconsistently present in the nerve)

| Branch | ||

| Dorsal scapular Origin: C5 root Spinal segment: C5 |

|

Function: motor Rhomboid major, rhomboid minor |

| Long thoracic Origin: C5 to C7 roots Spinal segments: C5 to C7 |

|

Function: motor Serratus anterior |

| Suprascapular Origin: Superior trunk Spinal segments: C5, C6 |

|

Function: motor Supraspinatus, infraspinatus |

| Nerve to subclavius Origin: Superior trunk Spinal segments: C5, C6 |

|

Function: motor Subclavius |

| Lateral pectoral Origin: Lateral cord Spinal segments: C5 to C7 |

|

Function: motor Pectoralis major |

| Musculocutaneous Origin: Lateral cord Spinal segments: C5 to C7 |

|

Function: motor All muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm Function: sensory Skin on lateral side of forearm |

| Medial pectoral Origin: Medial cord Spinal segments: C8, T1 (also receives contributions from spinal segments C5 to C7 through a communication with the lateral pectoral nerve) |

|

Function: motor Pectoralis major, pectoralis minor |

| Medial cutaneous of arm Origin: Medial cord Spinal segments: C8, T1 |

|

Function: sensory Skin on medial side of distal one-third of arm |

| Medial cutaneous of forearm Origin: Medial cord Spinal segments: C8, T1 |

|

Function: sensory Skin on medial side of forearm |

| Median Origin: Medial and lateral cords Spinal segments: (C5), C6 to T1 |

|

Function: motor All muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm (except flexor carpi ulnaris and medial half of flexor digitorum profundus), three thenar muscles of the thumb and two lateral lumbrical muscles Function: sensory Skin over the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits and over the lateral side of the palm and middle of the wrist |

| Ulnar Origin: Medial cord Spinal segments: (C7), C8, T1 |

|

Function: motor All intrinsic muscles of the hand (except three thenar muscles and two lateral lumbricals); also flexor carpi ulnaris and the medial half of flexor digitorum profundus in the forearm Function: sensory Skin over the palmar surface of the medial one and one-half digits and associated palm and wrist, and skin over the dorsal surface of the medial one and one-half digits |

| Superior subscapular Origin: Posterior cord Spinal segments: C5, C6 |

|

Function: motor Subscapularis |

| Thoracodorsal Origin: Posterior cord Spinal segments: C6 to C8 |

|

Function: motor Latissimus dorsi |

| Inferior subscapular Origin: Posterior cord Spinal segments: C5, C6 |

|

Function: motor Subscapularis, teres major |

| Axillary Origin: Posterior cord Spinal segments: C5, C6 |

|

Function: motor Deltoid, teres minor Function: sensory Skin over upper lateral part of arm |

| Radial Origin: Posterior cord Spinal segments: C5 to C8, (T1) |

|

Function: motor All muscles in the posterior compartments of arm and forearm Function: sensory Skin on the posterior aspects of the arm and forearm, the lower lateral surface of the arm, and the dorsal lateral surface of the hand |

The only branches from the trunks of the brachial plexus are two nerves that originate from the superior trunk (upper trunk): the suprascapular nerve and the nerve to the subclavius muscle (Fig. 7.53).

The suprascapular nerve (C5 and C6):

originates from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus,

originates from the superior trunk of the brachial plexus,

passes laterally through the posterior triangle of the neck (Fig. 7.54) and through the suprascapular foramen to enter the posterior scapular region,

passes laterally through the posterior triangle of the neck (Fig. 7.54) and through the suprascapular foramen to enter the posterior scapular region,

innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, and

innervates the supraspinatus and infraspinatus muscles, and

is accompanied in the lateral parts of the neck and in the posterior scapular region by the suprascapular artery.

is accompanied in the lateral parts of the neck and in the posterior scapular region by the suprascapular artery.

The nerve to the subclavius muscle (C5 and C6) is a small nerve that:

Three nerves originate entirely or partly from the lateral cord (Fig. 7.53).

The lateral pectoral nerve is the most proximal of the branches from the lateral cord. It passes anteriorly, together with the thoraco-acromial artery, to penetrate the clavipectoral fascia that spans the gap between the subclavius and pectoralis minor muscles (Fig. 7.55), and innervates the pectoralis major muscle.

The lateral pectoral nerve is the most proximal of the branches from the lateral cord. It passes anteriorly, together with the thoraco-acromial artery, to penetrate the clavipectoral fascia that spans the gap between the subclavius and pectoralis minor muscles (Fig. 7.55), and innervates the pectoralis major muscle.

The musculocutaneous nerve is a large terminal branch of the lateral cord. It passes laterally to penetrate the coracobrachialis muscle and pass between the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles in the arm, and innervates all three flexor muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm, terminating as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

The musculocutaneous nerve is a large terminal branch of the lateral cord. It passes laterally to penetrate the coracobrachialis muscle and pass between the biceps brachii and brachialis muscles in the arm, and innervates all three flexor muscles in the anterior compartment of the arm, terminating as the lateral cutaneous nerve of the forearm.

The lateral root of the median nerve is the largest terminal branch of the lateral cord and passes medially to join a similar branch from the medial cord to form the median nerve (Fig. 7.55).

The lateral root of the median nerve is the largest terminal branch of the lateral cord and passes medially to join a similar branch from the medial cord to form the median nerve (Fig. 7.55).

The medial cord has five branches (Fig. 7.55).

The medial pectoral nerve is the most proximal branch. It receives a communicating branch from the lateral pectoral nerve and then passes anteriorly between the axillary artery and axillary vein. Branches of the nerve penetrate and supply the pectoralis minor muscle. Some of these branches pass through the muscle to reach and supply the pectoralis major muscle. Other branches occasionally pass around the inferior or lateral margin of the pectoralis minor muscle to reach the pectoralis major muscle.

The medial pectoral nerve is the most proximal branch. It receives a communicating branch from the lateral pectoral nerve and then passes anteriorly between the axillary artery and axillary vein. Branches of the nerve penetrate and supply the pectoralis minor muscle. Some of these branches pass through the muscle to reach and supply the pectoralis major muscle. Other branches occasionally pass around the inferior or lateral margin of the pectoralis minor muscle to reach the pectoralis major muscle.

The medial cutaneous nerve of the arm (medial brachial cutaneous nerve) passes through the axilla and into the arm where it penetrates deep fascia and supplies skin over the medial side of the distal third of the arm. In the axilla, the nerve communicates with the intercostobrachial nerve of T2. Fibers of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm innervate the upper part of the medial surface of the arm and floor of the axilla.

The medial cutaneous nerve of the arm (medial brachial cutaneous nerve) passes through the axilla and into the arm where it penetrates deep fascia and supplies skin over the medial side of the distal third of the arm. In the axilla, the nerve communicates with the intercostobrachial nerve of T2. Fibers of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm innervate the upper part of the medial surface of the arm and floor of the axilla.

The medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm (medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve) originates just distal to the origin of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm. It passes out of the axilla and into the arm where it gives off a branch to the skin over the biceps brachii muscle, and then continues down the arm to penetrate the deep fascia with the basilic vein, continuing inferiorly to supply the skin over the anterior surface of the forearm. It innervates skin over the medial surface of the forearm down to the wrist.

The medial cutaneous nerve of the forearm (medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve) originates just distal to the origin of the medial cutaneous nerve of the arm. It passes out of the axilla and into the arm where it gives off a branch to the skin over the biceps brachii muscle, and then continues down the arm to penetrate the deep fascia with the basilic vein, continuing inferiorly to supply the skin over the anterior surface of the forearm. It innervates skin over the medial surface of the forearm down to the wrist.

The medial root of the median nerve passes laterally to join with a similar root from the lateral cord to form the median nerve anterior to the third part of the axillary artery.

The medial root of the median nerve passes laterally to join with a similar root from the lateral cord to form the median nerve anterior to the third part of the axillary artery.

The ulnar nerve is a large terminal branch of the medial cord (Fig. 7.55). However, near its origin, it often receives a communicating branch from the lateral root of the median nerve originating from the lateral cord and carrying fibers from C7. The ulnar nerve passes through the arm and forearm into the hand where it innervates all intrinsic muscles of the hand (except for the three thenar muscles and the two lateral lumbrical muscles). On passing through the forearm, branches of the ulnar nerve innervate the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle. The ulnar nerve innervates skin over the palmar surface of the little finger, medial half of the ring finger, and associated palm and wrist, and the skin over the dorsal surface of the medial part of the hand.

The ulnar nerve is a large terminal branch of the medial cord (Fig. 7.55). However, near its origin, it often receives a communicating branch from the lateral root of the median nerve originating from the lateral cord and carrying fibers from C7. The ulnar nerve passes through the arm and forearm into the hand where it innervates all intrinsic muscles of the hand (except for the three thenar muscles and the two lateral lumbrical muscles). On passing through the forearm, branches of the ulnar nerve innervate the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle. The ulnar nerve innervates skin over the palmar surface of the little finger, medial half of the ring finger, and associated palm and wrist, and the skin over the dorsal surface of the medial part of the hand.

Median nerve.

The median nerve is formed anterior to the third part of the axillary artery by the union of lateral and medial roots originating from the lateral and medial cords of the brachial plexus (Fig. 7.55). It passes into the arm anterior to the brachial artery and through the arm into the forearm, where branches innervate most of the muscles in the anterior compartment of the forearm (except for the flexor carpi ulnaris muscle and the medial half of the flexor digitorum profundus muscle, which are innervated by the ulnar nerve).

The median nerve continues into the hand to innervate:

the three thenar muscles associated with the thumb,

the three thenar muscles associated with the thumb,

the two lateral lumbrical muscles associated with movement of the index and middle fingers, and

the two lateral lumbrical muscles associated with movement of the index and middle fingers, and

the skin over the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits and over the lateral side of the palm and middle of the wrist.

the skin over the palmar surface of the lateral three and one-half digits and over the lateral side of the palm and middle of the wrist.

The musculocutaneous nerve, the lateral root of the median nerve, the median nerve, the medial root of the median nerve, and the ulnar nerve form an M over the third part of the axillary artery (Fig. 7.55). This feature, together with penetration of the coracobrachialis muscle by the musculocutaneous nerve, can be used to identify components of the brachial plexus in the axilla.

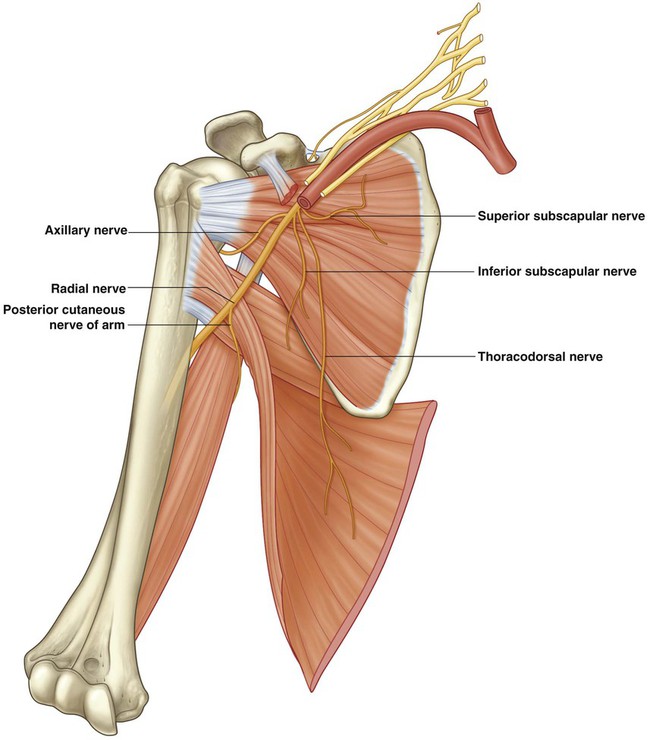

Branches of the posterior cord

Five nerves originate from the posterior cord of the brachial plexus:

The superior subscapular, thoracodorsal, and inferior subscapular nerves originate sequentially from the posterior cord and pass directly into muscles associated with the posterior axillary wall (Fig. 7.56). The superior subscapular nerve is short and passes into and supplies the subscapularis muscle. The thoracodorsal nerve is the longest of these three nerves and passes vertically along the posterior axillary wall. It penetrates and innervates the latissimus dorsi muscle. The inferior subscapular nerve also passes inferiorly along the posterior axillary wall and innervates the subscapularis and teres major muscles.

The axillary nerve originates from the posterior cord and passes inferiorly and laterally along the posterior wall to exit the axilla through the quadrangular space (Fig. 7.56). It passes posteriorly around the surgical neck of the humerus and innervates both the deltoid and teres minor muscles. A superior lateral cutaneous nerve of the arm originates from the axillary nerve after passing through the quadrangular space and loops around the posterior margin of the deltoid muscle to innervate skin in that region. The axillary nerve is accompanied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery.

The radial nerve is the largest terminal branch of the posterior cord (Fig. 7.56). It passes out of the axilla and into the posterior compartment of the arm by passing through the triangular interval between the inferior border of the teres major muscle, the long head of the triceps brachii muscle, and the shaft of the humerus. It is accompanied through the triangular interval by the profunda brachii artery, which originates from the brachial artery in the anterior compartment of the arm. The radial nerve and its branches innervate:

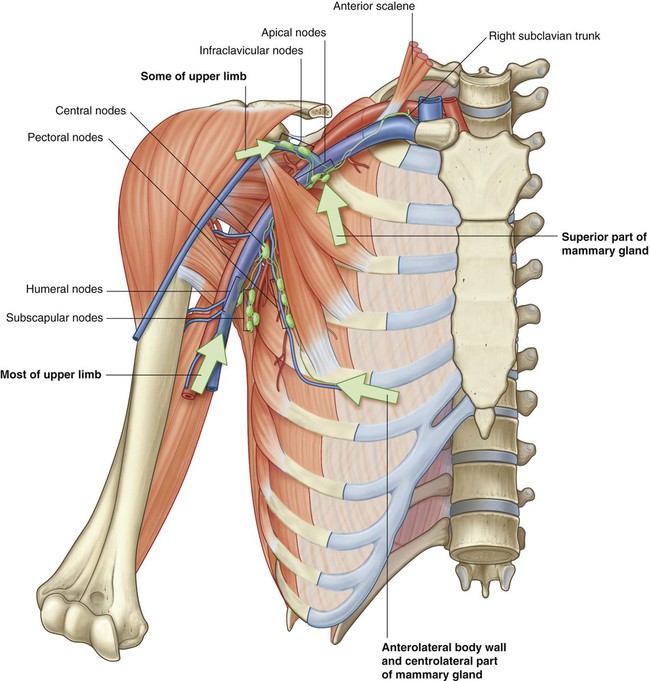

Lymphatics

All lymphatics from the upper limb drain into lymph nodes in the axilla (Fig. 7.57).

The 20–30 axillary nodes are generally divided into five groups on the basis of location.

Humeral (lateral) nodes posteromedial to the axillary vein receive most of the lymphatic drainage from the upper limb.

Humeral (lateral) nodes posteromedial to the axillary vein receive most of the lymphatic drainage from the upper limb.

Pectoral (anterior) nodes occur along the inferior margin of the pectoralis minor muscle along the course of the lateral thoracic vessels and receive drainage from the abdominal wall, the chest, and the mammary gland.

Pectoral (anterior) nodes occur along the inferior margin of the pectoralis minor muscle along the course of the lateral thoracic vessels and receive drainage from the abdominal wall, the chest, and the mammary gland.

Subscapular (posterior) nodes on the posterior axillary wall in association with the subscapular vessels drain the posterior axillary wall and receive lymphatics from the back, the shoulder, and the neck.

Subscapular (posterior) nodes on the posterior axillary wall in association with the subscapular vessels drain the posterior axillary wall and receive lymphatics from the back, the shoulder, and the neck.

Central nodes are embedded in axillary fat and receive tributaries from humeral, subscapular, and pectoral groups of nodes.

Central nodes are embedded in axillary fat and receive tributaries from humeral, subscapular, and pectoral groups of nodes.

Apical nodes are the most superior group of nodes in the axilla and drain all other groups of nodes in the region. In addition, they receive lymphatic vessels that accompany the cephalic vein as well as vessels that drain the superior region of the mammary gland.

Apical nodes are the most superior group of nodes in the axilla and drain all other groups of nodes in the region. In addition, they receive lymphatic vessels that accompany the cephalic vein as well as vessels that drain the superior region of the mammary gland.

Axillary process of the mammary gland

Although the mammary gland is in superficial fascia overlying the thoracic wall, its superolateral region extends along the inferior margin of the pectoralis major muscle toward the axilla. In some cases, this may pass around the margin of the muscle to penetrate deep fascia and enter the axilla (Fig. 7.58). This axillary process rarely reaches as high as the apex of the axilla.

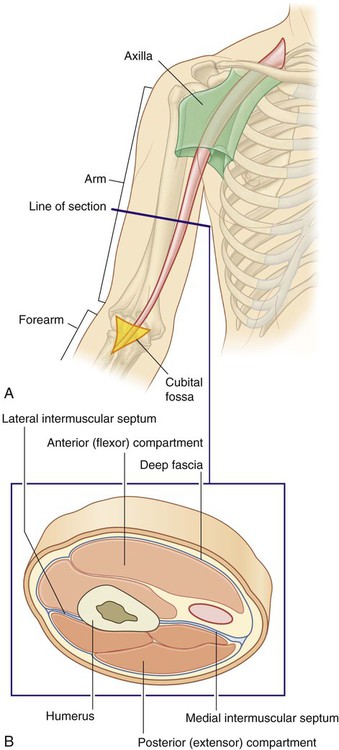

Arm

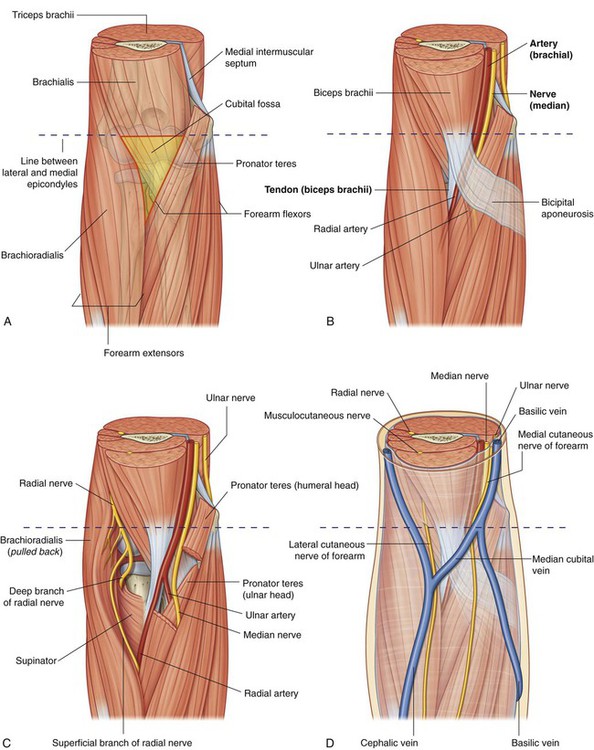

The arm is the region of the upper limb between the shoulder and the elbow (Fig. 7.59). The superior aspect of the arm communicates medially with the axilla. Inferiorly, a number of important structures pass between the arm and the forearm through the cubital fossa, which is positioned anterior to the elbow joint.

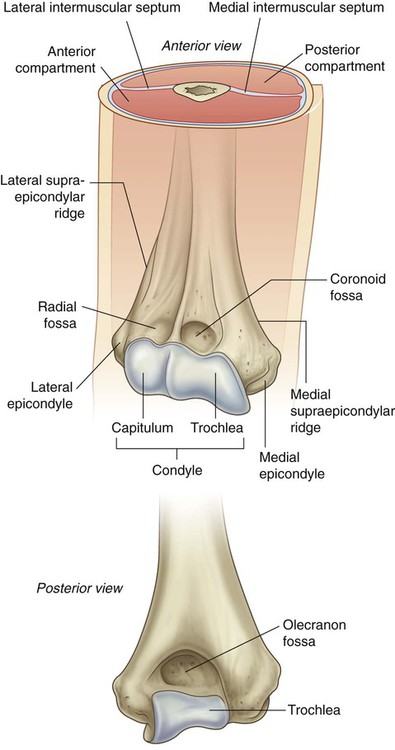

The arm is divided into two compartments by medial and lateral intermuscular septa, which pass from each side of the humerus to the outer sleeve of deep fascia that surrounds the limb (Fig. 7.59).

Bones

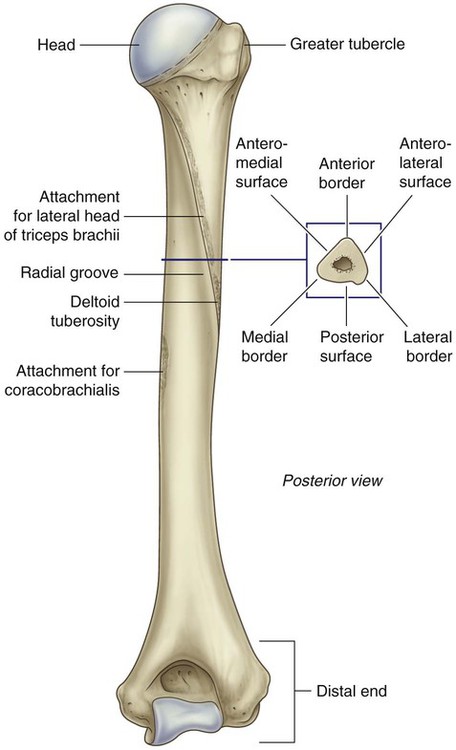

The skeletal support for the arm is the humerus (Fig. 7.60). Most of the large muscles of the arm insert into the proximal ends of the two bones of the forearm, the radius and the ulna, and flex and extend the forearm at the elbow joint. In addition, the muscles predominantly situated in the forearm that move the hand originate at the distal end of the humerus.

Shaft and distal end of the humerus

In cross section, the shaft of the humerus is somewhat triangular with:

anterior, lateral, and medial borders, and

anterior, lateral, and medial borders, and

anterolateral, anteromedial, and posterior surfaces (Fig. 7.60).

anterolateral, anteromedial, and posterior surfaces (Fig. 7.60).

Intermuscular septa, which separate the anterior compartment from the posterior compartment, attach to the medial and lateral borders (Fig. 7.61).

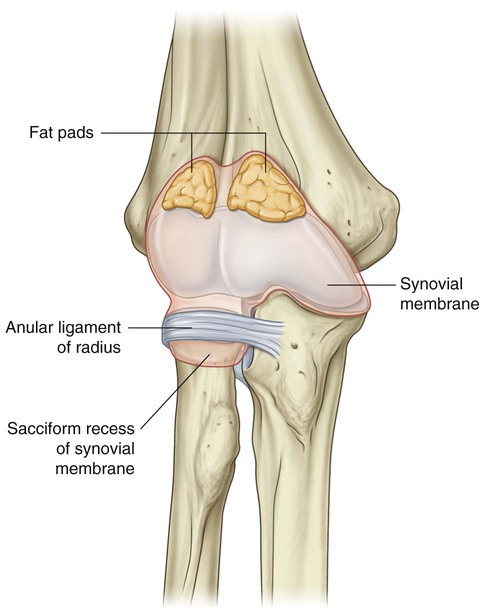

The distal end of the humerus, which is flattened in the anteroposterior plane, bears a condyle, two epicondyles, and three fossae, as follows (Fig. 7.61).

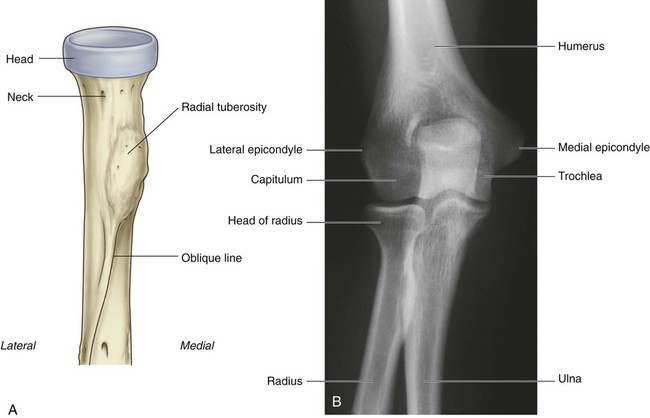

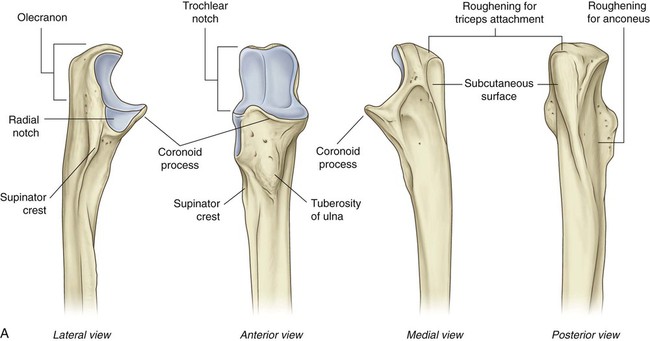

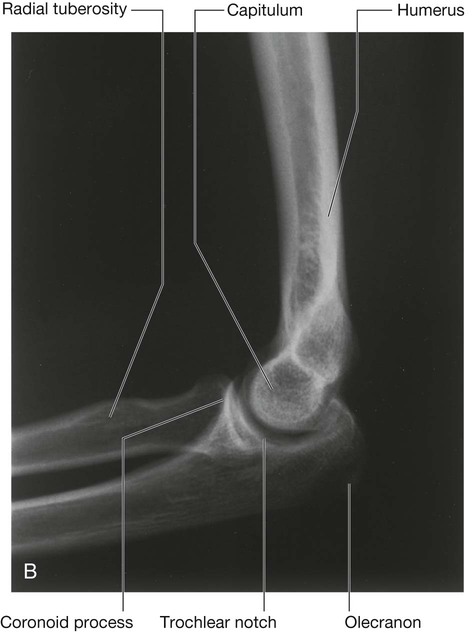

Proximal end of the ulna

The proximal end of the ulna is much larger than the proximal end of the radius and consists of the olecranon, the coronoid process, the trochlear notch, the radial notch, and the tuberosity of the ulna (Fig. 7.63A,B).

B. Radiograph of the elbow joint (lateral view).

The coronoid process projects anteriorly from the proximal end of the ulna (Fig. 7.63). Its superolateral surface is articular and participates, with the olecranon, in forming the trochlear notch. The lateral surface is marked by the radial notch for articulation with the head of the radius.

Muscles

Coracobrachialis

The coracobrachialis muscle extends from the tip of the coracoid process of the scapula to the medial side of the midshaft of the humerus (Fig. 7.64 and Table 7.8). It passes through the axilla and is penetrated and innervated by the musculocutaneous nerve.

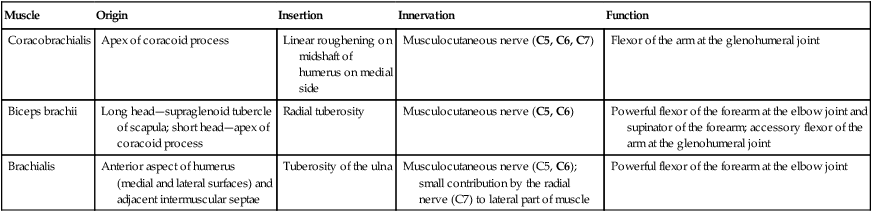

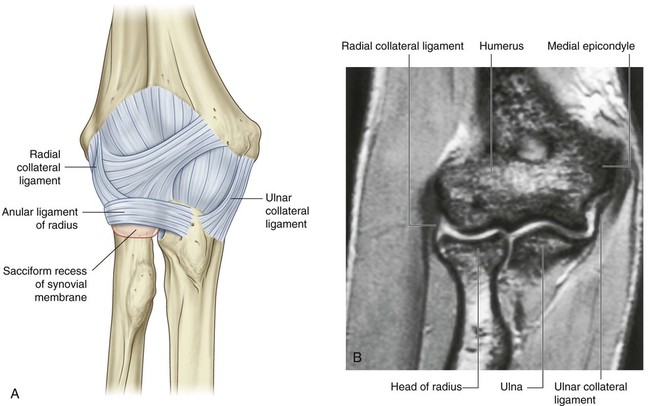

Table 7.8

Muscles of the anterior compartment of the arm (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Coracobrachialis | Apex of coracoid process | Linear roughening on midshaft of humerus on medial side | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6, C7) | Flexor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Biceps brachii | Long head—supraglenoid tubercle of scapula; short head—apex of coracoid process | Radial tuberosity | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6) | Powerful flexor of the forearm at the elbow joint and supinator of the forearm; accessory flexor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

| Brachialis | Anterior aspect of humerus (medial and lateral surfaces) and adjacent intermuscular septae | Tuberosity of the ulna | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5, C6); small contribution by the radial nerve (C7) to lateral part of muscle | Powerful flexor of the forearm at the elbow joint |

Biceps brachii

The biceps brachii muscle has two heads:

The short head of the muscle originates from the coracoid process in conjunction with the coracobrachialis.

The short head of the muscle originates from the coracoid process in conjunction with the coracobrachialis.

The long head originates as a tendon from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula (Fig. 7.64 and Table 7.8).

The long head originates as a tendon from the supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula (Fig. 7.64 and Table 7.8).

The long and short heads converge to form a single tendon, which inserts onto the radial tuberosity.

Brachialis

The brachialis muscle originates from the distal half of the anterior aspect of the humerus and from adjacent parts of the intermuscular septa, particularly on the medial side (Fig. 7.64 and Table 7.8). It lies beneath the biceps brachii muscle, is flattened dorsoventrally, and converges to form a tendon, which attaches to the tuberosity of the ulna.