7 Upper gastrointestinal disease and disorders of the small bowel

Oesophagus – dysphagia

Many conditions of the oesophagus present with dysphagia. If chronic there is nearly always associated weight loss. Dysphagia may be progressive, suggesting a malignant growth or stricture, or non-progressive, suggesting a disorder of function. Conditions of the oesophagus may be divided into causes in the lumen, in the wall or outside the lumen. In addition, some neurological conditions may also cause dysphagia (Box 7.1).

Oesophageal perforation

• iatrogenic following therapeutic dilatation

• Boerhaave’s syndrome (perforation due to violent vomiting).

Hiatus hernia

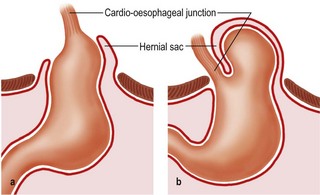

Two types of hiatus hernia are described: sliding (90%) and rolling (para-oesophageal). In the latter, the gastrooesophageal sphincter remains intact and reflux does not occur (Fig. 7.1). The common sliding hiatus hernia disrupts and changes the oesophago-gastric junction, giving rise to reflux.

Long-term complications include ulceration, Barrett’s oesophagus, bleeding and stricture.

Carcinoma of the oesophagus

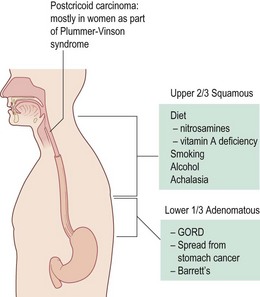

The incidence in Europe is 2–8 cases/100 000. It is much higher in the Far East (100–150/100 000). Males are more commonly affected. The aetiology of oesophageal cancer is summarised in Figure 7.2.

Investigation

Peptic ulceration

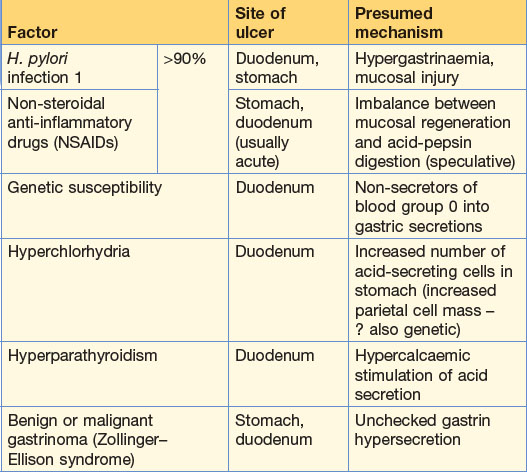

Peptic ulceration includes ulceration of the stomach, duodenum, lower oesophagus and Meckel’s diverticulum related to excess acid production and Helicobacter pylori. Predisposing factors include smoking, NSAIDs, poor socioeconomic conditions and H. pylori infection. The causes of peptic ulceration are summarised in Table 7.1.

Clinical features of duodenal (DU) and gastric (GU) ulcers

Treatment

GUs require repeat endoscopy after 6 weeks to check healing and exclude malignancy.

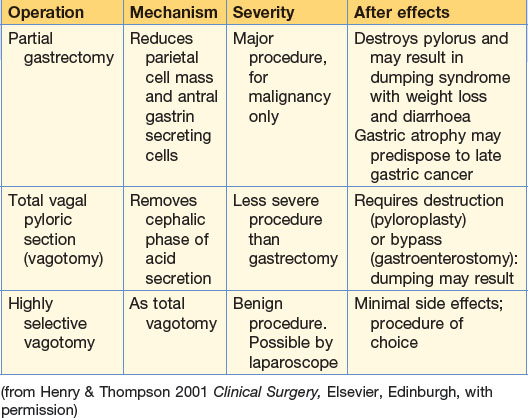

The principal aims of duodenal ulcer surgery are to reduce acid production by reducing parietal cell mass or abolition of cephalic phase of acid secretion (vagotomy) (Table 7.2). Indications for gastric surgery are shown in Box 7.2.

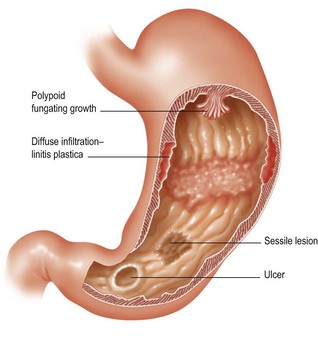

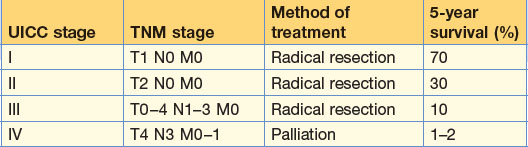

Gastric carcinoma

Clinical features

The best sign is no sign, since more advanced tumours are usually incurable.

Acute upper GI bleeding

Management

Requirements for blood are shown in Table 7.4. When the patient is stable a detailed history and examination may be obtained to establish the cause (Table 7.5). OGD is essential to achieve a diagnosis within 24 hours.

Table 7.4 Guidelines for cross-matching and transfusion of blood in upper GI bleeds

| Clinical state | Action |

|---|---|

| Without haemodynamic problems | None |

| With haemodynamic problem | 4 units |

| Anaemic (Hb <10 g/dL) | 1 unit of blood for every 1 g deficit below 10 g/dL |

| Continued bleeding | Guided by clinical features but at least 4 units |

| Re-bleed if under 60 years | No action unless there is haemodynamic instability |

| Re-bleed if over 60 years | 4 units |

Table 7.5 Salient historical features in common causes of haematemesis

| Cause | Mechanism | Historical features |

|---|---|---|

| Mucosal tear at cardia (Mallory–Weiss syndrome) | Forceful attempted vomiting | Acute inebriation Initial clear vomit Bright red haematemesis |

| Oesophageal varices | Rupture or erosion of mucosa over varix | Past liver disease Absence of peptic ulcer history Dark red haematemesis |

| NSAID-induced erosions | Breakdown of mucosal barrier to acid | Pain-producing associated disorder (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis) Intake of NSAID, including low-dose aspirin |

| Peptic ulcer | Peptic digestion of vessel in base of ulcer Fibrinoid necrosis of vessel holding lumen open Exacerbation of ulceration by NSAIDs |

Previous episodes of dyspepsia Diagnosed ulcer Recent worsening of symptoms Blood of variable colour with or without clots |

| Angiodysplaslas | Rupture or mucosal digestion of a surface lesion | No history on initial occurrence |

| Other causes to consider | Varies with cause | Examples: History of anticoagulant intake Haematological disorders |

Peptic ulcer

Many bleeds are self-limiting. Withdrawal of NSAIDs and treatment with PPIs or H2 receptor antagonists is effective. Patients more likely to re-bleed are elderly, with a large ulcer with endoscopic stigmata of visible vessel, adherent clot, black spot in the ulcer crater or actively bleeding vessel (Table 7.6). The decision to operate should be made in a multidisciplinary setting (Table 7.7). Absence of H. pylori is confirmed by 13C urea breath test or by stool sample.

| Class of evidence | Features |

|---|---|

| Haemodynamic evidence of continued blood loss after resuscitation | Persistent – low or falling CVP; tachycardia; hypotension |

| Clinical evidence of continued or repeated bleeding | Further fresh haematemesis (not old blood) Melaena |

| Re-endoscopy | Visible fresh bleeding |

| Haematological | Progressive haemodilution beyond 24 hours |

Table 7.7 Indications for surgery for a bleeding duodenal ulcer

| Timing | Age (years) | Basis of decision |

|---|---|---|

| Immediate | Any | Uncontrollable spurting vessel at endoscopy Clinical exsanguination |

| Delayed | Over 60 | More than 4 units of blood required for haemodynamic stabilisation or more than 8 units over 48 hours |

| Under 60 | More than 8 units necessary for stabilisation or more than 12 units needed over 48 hours | |

| On rebleeding | Over 60 | One re-bleed after initial successful control but while still in hospital |

| Under 60 | Two re-bleeds after initial successful control but while still in hospital |

Disorders of the small bowel

Meckel’s diverticulum

This is a remnant of the vitello-intestinal duct of the embryo which classically occurs in 2% of patients, is 5 cm long and 60 cm from the ileocaecal junction. It occurs on the antimesenteric border of the terminal ileum (Figure 7.4).

Crohn’s disease

Clinical features

Chronic

Crohn’s colitis resembles ulcerative colitis (p. 149, p. 152); the clinical features are similar. There may be symptoms of ill health, weight loss, abdominal pain and diarrhoea. A mass may be present in the RIF. There may be signs of the ‘Crohn’s anus’: skin tags, fissuring and scarring from previous perianal abscess. Other clinical signs that may suggest the diagnosis include clubbing, erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum and uveitis.