Chapter 17 Upper body lift with lateral excision

• Upper body lift. This combination of single procedures is described and compared to single stage techniques.

• The main technical aspects are highlighted and described in the clinical context.

• Prevention, reduction and management of complications are demonstrated for this specific procedure.

• Different intraoperative steps are explained to enable procedure enhancement.

• The combination of liposuction and upper body contouring procedures has to be performed cautiously and restricted. Therefore, limitations are emphasized.

Introduction

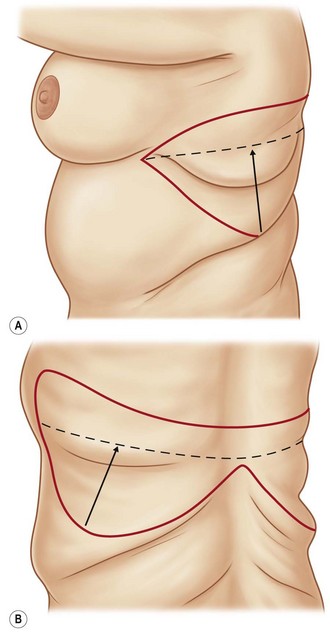

In the past, reconstructive operations such as breast reshaping, arm- and back-lifts were performed as single-stage procedures, especially for patients after massive weight loss. As part of a progression in this specific subfield of plastic surgery, modern treatment concepts have been established, such as the upper body lift, with or without a circumferential upper thoracic lift.1–7 Besides the reconstruction of the breast with implants or alternatively with autologous tissues from the upper abdomen and/or lateral thorax, these regions can be sufficiently tightened in a single procedure, positioning the scar as a continuation of the submammary fold, ascending to the axillary crease. Patients with mild to moderate skin and tissue excess in the dorsal thoracic region can benefit from a sufficient skin tightening in this area by this approach. The upper arm reconstruction can easily be continued, without any interaction with the axillary reconstruction. In individual cases with severe skin excess at the dorsal thorax, a direct approach in terms of a bra-line lift can be performed4 (Fig. 17.1).

Preoperative Preparation

For general information please refer to Chapter 38.

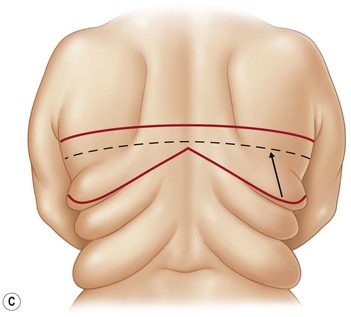

The decision for an upper body lift is made on the extent of skin and soft tissue excess at the lateral and dorsal thoracic wall. The classification of the lateral folds after massive weight loss is designated by Strauch et al into an upper breast roll, followed by a lower scapular roll or a deeper lower chest/thoracic roll. An analogous classification is made for the iliac area as hip rolls. The folds can be seen individually, often with a fluent passage.8 The two upper folds often can be treated by various surgical options and are only peripherally influenced by the lower body lift alone, whereas the two lower folds can only effectively be treated by a lower body lift or a belt lipectomy (Fig. 17.2).

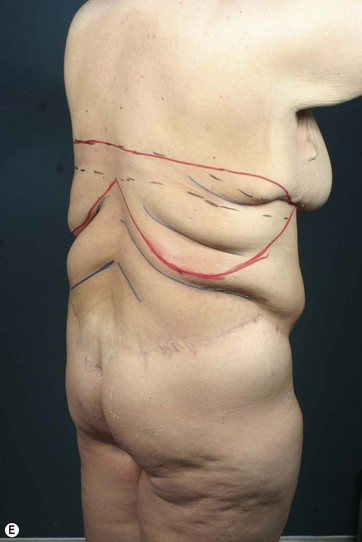

Markings

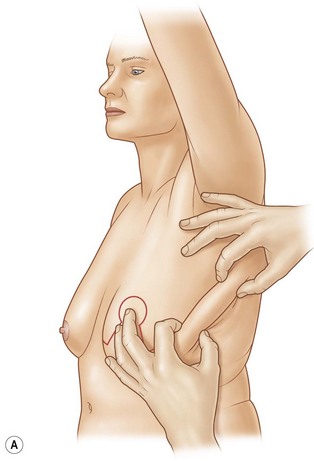

Marking of the breast procedure is performed so that it is personalized to the patient. Regarding the new nipple–areola complex position, we emphasize the measurement of it proportional to the submammary fold and the upper breast border. Since women with low submammary folds have an appropriately low upper breast border, a high nipple–areola complex may lead to an early postoperative bottoming out. We prefer the central pedicle with dermal suspension as presented by Rubin and the double-ellipse technique for the arm reconstruction as published by Aly.2,9

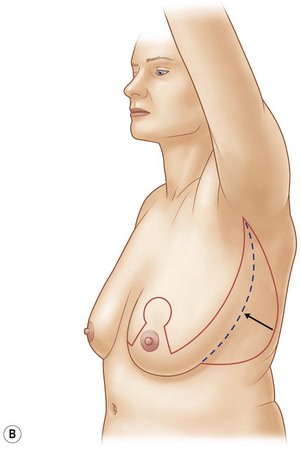

This maneuver allows a transposition and rotation of the lateral and dorsal soft-tissue cranial and anterior, with a resulting scar that is located at the medial or posterior axillary line. The lateral tension from the back may cause a lateralization of the breast which must be considered during the markings for the breast. The position of the nipple–areola complex should always be double-checked after finishing the upper lateral-thoracic-lift.4–6

Surgical Technique

Upper Lateral Thoracic Lift

The conventional surgical treatment of the upper two back and lateral rolls by direct excision at the aspect of the dorsal thorax often leads to wide, unsightly and permanent visible scars. Respecting the different interfering units of the upper body, and in terms of reduction of operating and recovery time and improving patient outcome, we combine the upper arm lift with breast reshaping and the upper-lateral thoracic lift as an integrated treatment in appropriate cases. Using the combination technique, a continuous approach is performed from the medial submammary fold via an anterior and posterior axillary incision line distally to the elbow. In this regard, the circumferential vectors eliminate the upper breast and lower scapular rolls and a horizontal tension to the central zone over the vertebral column is ensured (Fig. 17.3).

Starting with the upper arm lift, which is mostly performed in terms of the double-ellipse technique as described by Aly,2 we continue passing the axillary crease. The upper-lateral thoracic lift is followed in terms of a direct and indirect excisional procedure, mobilizing the dorsal and lateral thorax region. In female patients, we preferably address the breast deformities in a 45–60° upright patient positioning, performing the Rubin technique with a central pedicle and cranial fixation to preserve volume and prevent bottoming out, which is a common complication in this patient group due to the extremely thin atonic skin quality. In male patients, we generally perform the excisional technique with a pedicled breast reduction with simultaneous liposuction, resulting in best achievable results in this patient group. This intraoperative sequence ensures that the nipple–areola complex is not set too laterally and that you are able to compensate for the lateral pull being created with the upper-lateral thoracic lift. In the axillary crease the running scar may be disrupted with a Z plasty to prevent postoperative scar contraction.

Optimizing Outcomes

A more common and favorable procedure for contour improvement of the dorsal thoracic region is the upper-lateral thoracic lift, intended for patients after massive weight loss with consequent skin and soft-tissue redundancy in the lateral and dorsal thoracic region with or without lateral and back folds. It enables sufficient tissue elimination in different neighboring regions, conventionally seen as different anatomical units, by optimal scar placement. Optionally, this can be performed alone or as an integral part of a combined contouring procedure of the upper arm, the lateral and dorsal thoracic wall, as well as the female or male breast. In female patients it is usually combined with an inverted-T pattern breast reshaping, elongating the submammary incision to the axillary crease. In male patients we perform the direct excisional procedure for breast reshaping after massive weight loss, optionally with a free nipple graft, as popularized by Aly or as a pedicled transfer as recently described by Gusenoff or Stoff.2,10,11 The submammary scar is ideally placed at the inferior boundary of the pectoralis major muscle, continuing well hidden at the lateral thoracic wall to the axillary crease.

Scar formation in upper body contouring is well accepted by patients, though results differ widely in quality and appearance due to atonic skin quality with poor elasticity after significant damage to extracellular matrix components during obesity and bariatric surgery.12 In this regard, patients should be told clearly about revisional surgery, since the rate for secondary corrections in this patient group is relatively high due to secondary skin and tissue relaxation.

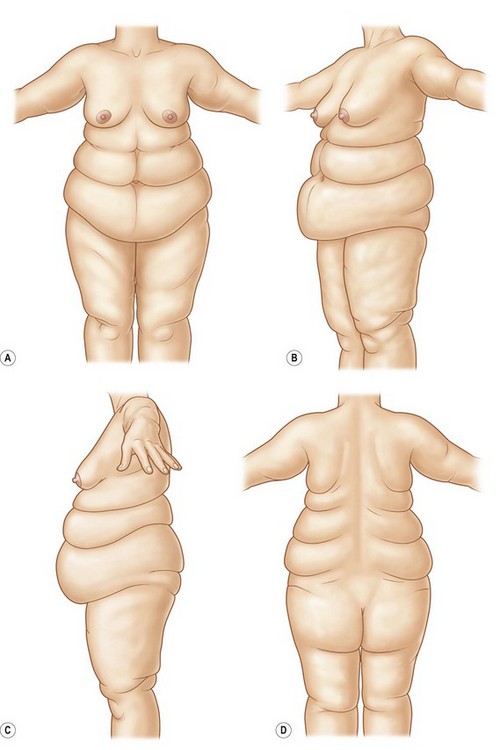

Some representative case studies are shown in Figs 17.4–17.8.

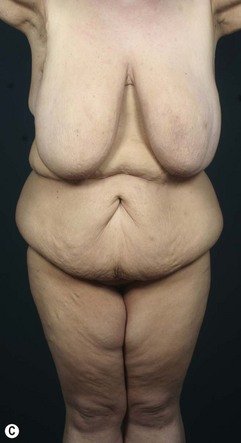

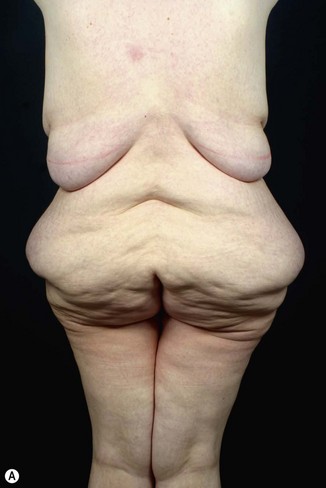

FIG. 17.6 Preoperative posterior, lateral and front view of a 42-year-old patient after 70 kg weight loss.

Postoperative Care

The postoperative management after upper body lift procedures is similar to lower body lift procedures (see Chapter 38). However, patients are not monitored on the intensive care unit. Early patient mobilization from day 1 with adequate thrombosis prophylaxis from low molecular weight heparin and a specially adjusted compression garment for 8 weeks postoperatively are mandatory.

1 Aly AS, Cram AE, Chao M, et al. Belt lipectomy for circumferential truncal excess: The University of Iowa experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;111:398.

2 Aly AS. Body Contouring after Massive Weight Loss. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2006.

3 Hurwitz DJ. Single-staged total body lift after massive weight loss. Ann Plast Surg. 2004;52(5):435–441. discussion 441

4 Hurwitz DJ, Holland SW. The L brachioplasty: an innovative approach to correct excess tissue of the upper arm, axilla, and lateral chest. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(2):403–411. discussion 412–3

5 Hurwitz DJ, Agha-Mohammadi S. Postbariatric surgery breast reshaping: the spiral flap. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56(5):481–486. discussion 486

6 Richter DF, Stoff A. The upper lateral thoracic lift. Plastic Surgery Pulse News. Volume 2, No 2. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing; 2010.

7 Richter DF, Stoff A. Back and lateral fold contouring. In: Nahai F, ed. The Art of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery. St. Louis: Quality Medical Publishing, 2010.

8 Strauch B, Herman C, Rohde C, et al. Mid-body contouring in the post-bariatric surgery patient. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117(7):2200–2211.

9 Rubin JP. Mastopexy after massive weight loss: dermal suspension and total parenchymal reshaping. Aesthet Surg J. 2006;26(2):214–222.

10 Stoff A, Velasco-Laguardia FJ, Richter DF. Central pedicled breast reduction technique in male patients after massive weight loss. Obes Surg. 2012;22(3):445–451.

11 Gusenoff JA, Coon D, Rubin JP. Pseudogynecomastia after massive weight loss: detectability of technique, patient satisfaction, and classification. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(5):1301–1311.

12 Rohrich RJ, Gosman AA, Conrad MH, et al. Simplifying circumferential body contouring: the central body lift evolution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118(2):525–535. discussion 536–538

Hunstad JP, Repta R. Bra-line back lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(4):1225–1228.

Orpheu SC, Coltro PS, Scopel GP, et al. Collagen and elastic content of abdominal skin after surgical weight loss. Obes Surg. 2010;20(4):480–486.

Rubin JP, Nguyen V, Schwentker A. Perioperative management of the post-gastric-bypass patient presenting for body contour surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2004;31(4):601–610. vi. Review