CHAPTER 8 Upper Blepharoplasty: Volume Enhancement via Skin Approach: Lowering the Upper Lid Crease

Over the years, success of a particular surgical procedure, even aesthetic, has been measured mostly by perceived outcome and to some degree by the frequency of complications. Since the overwhelming majority of aesthetic periorbital ‘complications’ have occurred with lower blepharoplasty, most of the attention on newer and improved techniques has focused on the lower periorbita1–6 (see Chapters 14–19, Lower blepharoplasty).

As functional misadventures are a much less encountered occurrence after upper blepharoplasty, complacency with existing methods and perpetuation of ill-perceived solutions to rejuvenation of the upper periorbita prevail.7,8

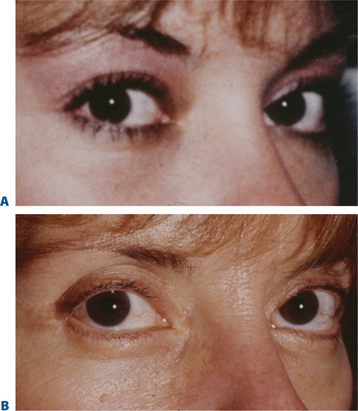

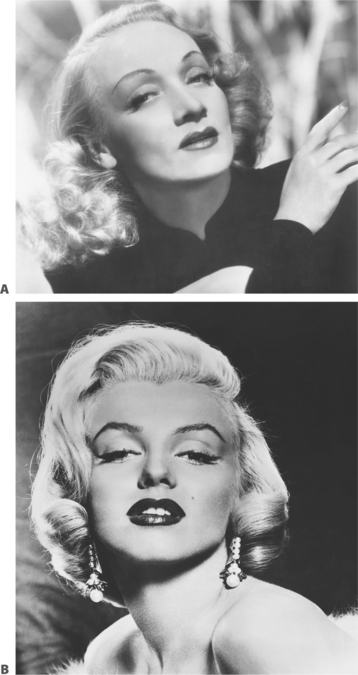

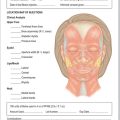

With rare exception, the approach to upper blepharoplasty has not been particularly physiologic or individualized and the universal application of traditional remedies for upper periorbital rejuvenation has translated to mediocrity.7–9 The prevailing perception has been that the appearance of the aged upper eyelid is primarily due to excessive skin, muscle, and fat often in conjunction with brow descent. Additionally, there is the confounding erroneous memory in many individuals of what their upper periorbita looked like in youth. Finally, there is the influence of the ‘famous and beautiful’ people on what patients may request for their eventual appearance despite their configuration in earlier years (Fig. 8-1) that may explain some of the historical aesthetic desires as well as changes in ideas and what is currently expected after surgery.

The consultation

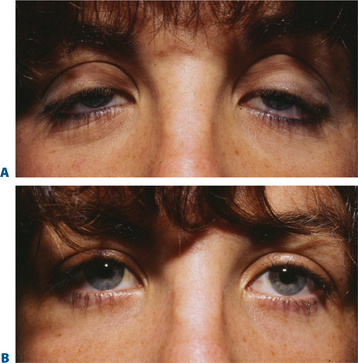

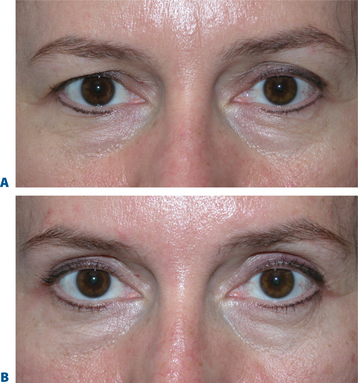

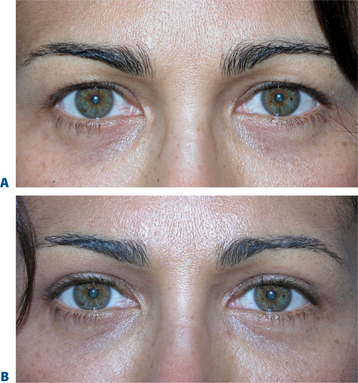

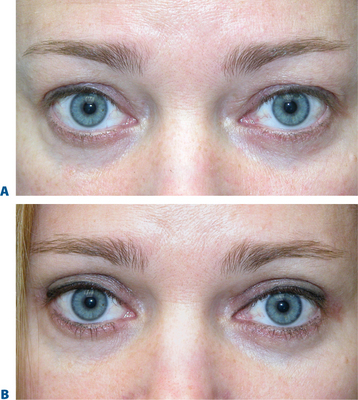

As with all surgical approaches to rejuvenation, we must take into account what are the actual changes that occur in the upper periorbita and whether the existing methods consider these occurrences for a wide variety of individual presentations (Fig. 8-2). Do these techniques result in a rejuvenative appearance or simply achieve a ‘cause and effect’ outcome whereby an altered appearance replaces youth? (Fig. 8-3). And, ultimately, what surgical procedures are some patients willing to undergo and what do they expect from surgery?

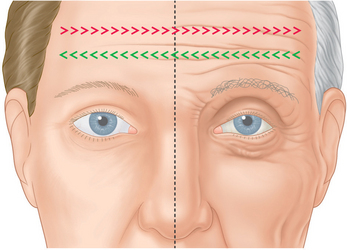

Often when a patient consults with one or a number of surgeons in consideration of rejuvenation of the upper periorbita, the possibility of brow lift is discussed. Some surgeons may suggest that a patient requires a brow lift while others may not. What is the basis of this inconsistency and what has been the justification and anatomic rationalization of either approach? Moreover, if the patient who presents for upper periorbital rejuvenation has a mild to moderate degree of perceived brow ptosis and refuses to undergo a brow lift of any sort, are there other methods that can significantly improve the appearance without the incorporation of browplasty/pexy?

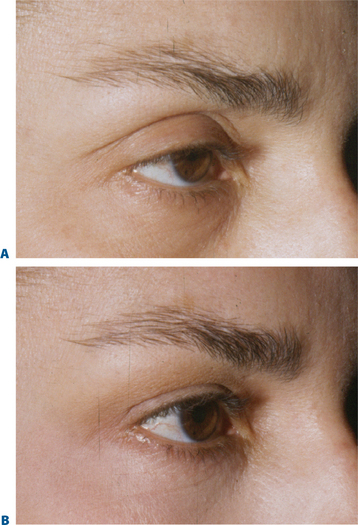

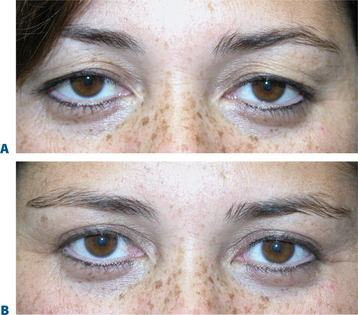

We are all aware that at times particular procedures are offered for lack of knowledge or ability to achieve a desired effect in another, perhaps more accurate, manner. For instance, when consulting with a young female who presents for improvement of the appearance of the upper periorbita, what are the findings on examination that suggest a particular approach? How much has the eyebrow actually descended and why would one then offer a brow lift if there has been little change over the patient’s lifetime? (Fig. 8-4). What has been the justification and anatomic rationalization of any given approach?9 What effects have been ignored with this approach that could be improved upon? Is there ever an indication for a 35 to 40-year-old (or younger) to have a brow lift? (Fig. 8-5). Have we considered what this individual patient’s brow position was in youth? Why, in fact, are many patients resistant to brow lifts? What should we strive for to accomplish the most acceptable and aesthetic rejuvenative result? A review of some simple but common observations of the changes in the aging upper periorbita for a majority of our patients sheds more light on which surgical solutions are both physiologically and aesthetically feasible (Figs 8-2, 8-6):

Eyebrow position and volume

The term brow ptosis suggests a descent of the eyebrow position from its ‘normal’ state. Obviously some younger individuals with ‘low’ brows may request a ‘change’ or improvement of their brow position much as one would desire otoplasty or rhinoplasty (Fig. 8-5). Additionally, many patients will present wishing for surgical correction to accomplish more pretarsal ‘show’ for reasons that include creating more area to apply cosmetics, a mistaken memory of what their upper eyelid looked like in youth, or simply their desired outcome. A review of old photographs is most often revealing, yet the ultimate determination must rest on the choice of each individual patient. Careful analysis including the use of morphing techniques as shown by Lambros11 and others,12 repeatedly and consistently has shown that the deflationary effects from facial volume loss with age can yield the apparent and illusionary effects of facial soft tissue ptosis. These misperceptions include an illusion of brow ptosis in some individuals that is due to soft tissue volume depletion, particularly in the temporal and lateral infrabrow regions, which may have prompted a brow lift when replacement of soft tissue volume has been shown to enhance aesthetics (Fig. 8-7)13 (see Chapter 23). There are also some individuals who would have compromised aesthetic results by not undergoing the necessary brow lift. Which individuals then, benefit from which procedures?

The upper eyelid crease and fold

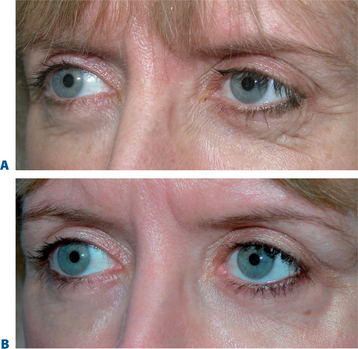

What has been less understood, are the actual changes that occur to the upper eyelid crease and fold. Often the position of the eyelid crease is obscured by the appearance of redundant upper eyelid skin and fold displacement. A careful analysis of the crease in most individuals shows varied change from youth. The changes may also be asymmetric in any one individual (Fig. 8-8). This includes an elevated crease that may manifest in one or both upper eyelids. The solution has been, in most cases, to raise the eyelid crease of the affected upper eyelid with the excision of ‘excess’ soft tissue with or without brow lift. This maneuver, however, is routinely and repeatedly performed without respect for the presenescent appearance or understanding of the actual age-related changes of the upper periorbita (Figs 8-2, 8-3, 8-6).

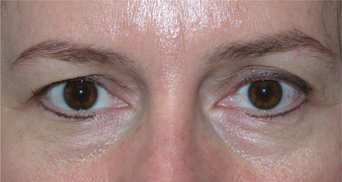

The routine applications of traditional concepts in incision placement and soft tissue excision have also plagued some other technical aspects in upper blepharoplasty. The usual design of the upper eyelid crease commonly involves the use of 10 mm or greater (height) eyelid crease incision with excision of skin, orbicularis oculi muscle, and preaponeurotic fat.7,8 This is customary whether or not upper blepharoplasty is performed with or without a brow lift. In part, the basis of this approach has been an attempt to elevate the upper eyelid crease, in essence, to expose a greater amount of the pretarsal surface and to ‘debulk’ the upper eyelid fullness by en-bloc or separate resection of skin and muscle.8 This approach, however, facilitated additional steps in upper blepharoplasty that are also aesthetically detrimental, including better access to the preaponeurotic fat (resulting in further soft tissue reduction and volume depletion) and the levator aponeurosis for supratarsal fixation. Concerns with a lower placed incision included possible visibility of the upper eyelid incision scar, inability to achieve adequate final pretarsal exposure, and risk to the levator aponeurosis insertion to the pretarsal surface, especially when utilizing a full thickness skin muscle excision whether removed in separate ‘layers’ or ‘en-bloc.’ The long-term consequences of the traditional approach, however, can be suboptimal. Deep or ‘hollow’ upper eyelid sulci are common effects, presumably from over-resection of soft tissue (Fig. 8-3), especially fat. In some, the upper eyelid crease scar becomes hypopigmented (Fig. 8-9) and usually more visible with time, usually at a much higher level (15–20 mm). This is especially true in the patient with a prominent globe, negative upper periorbital vector, or in those who habitually elevate their eyebrows for a variety of reasons. The color transition can also at times become quite obvious, as the upper edge of the incision is placed in the darker and thicker sub-brow skin. The pretarsal skin also becomes progressively less taut (more ‘crepey’ in appearance) due to the sliding effect as most original points of fixation have been compromised by over-dissection.

Comparative anatomy and aesthetics of upper eyelid ptosis and periorbital aging

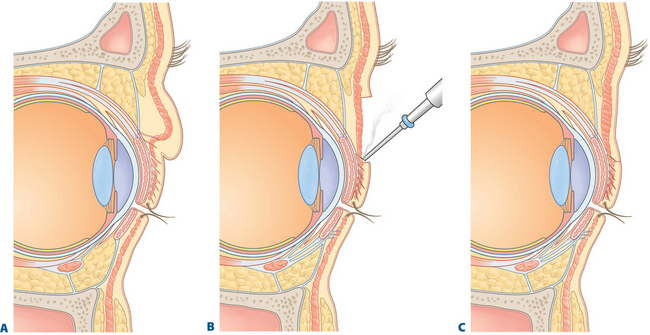

Some of the changes that can occur in the aging upper periorbita parallel the findings seen with true upper eyelid ptosis at any age. Alternative and improved surgical repair has shed light on the effects that can be created by alterations in the upper eyelid crease. Often in those with significant blepharoptosis, there is an apparent, unusually elevated (from youth), upper eyelid crease, at times >15–20 mm (Fig. 8-10A). This is also typically associated with a deep, hollow, upper eyelid sulcus and apparent volume depletion from either fat atrophy or retraction of the central preaponeurotic fat pad. This is further accentuated by the patient’s subconscious efforts to raise the eyebrow in an attempt to elevate the upper eyelid to enhance visual function (Figs 8-10A, 8-11A). Although the mechanism for these latter changes has been challenged (in both non-surgical and post-surgical14 states) I believe that it is, in part, a result of atrophic orbital effects causing loss of adherence of the multiple eyelid layers with subsequent loss of the lower positioned upper eyelid crease of youth. With this, the relationship of the levator aponeurosis and orbital septum loses the tight compartmentalization of the central preaponeurotic fat that is normally sandwiched between the levator aponerosis and orbital septum that now can retract into the orbit. Traditional methods of blepharoptosis repair using levator advancement or resection techniques have had much less predictable influences on the eyelid crease. These techniques led to variable excision of the skin and orbicularis oculi muscle, septum, and preaponeurotic fat in order to address the presumed levator aponeurosis dehiscence for repair. I believe this yields less aesthetic results and contributes to the appearance of upper periorbital aging. Minimally invasive surgical solutions to blepharoptosis repair15 (posterior approach/soft tissue sparing such as the Müller’s muscle conjunctival resection) even combined with skin excisional blepharoplasty may improve the upper eyelid soft tissue plane relationships by recreating supratarsal volume that re-establishes the youthful upper eyelid appearance (Figs 8-10, 8-11, see Chapter 11). The analogy of the aging upper periorbita with upper blepharoptosis and a greater sense of the physiologic and anatomic changes that occur in upper facial aging suggest a more sound and logical approach for rejuvenation.

Advanced rejuvenative upper blepharoplasty from technique to aesthetics

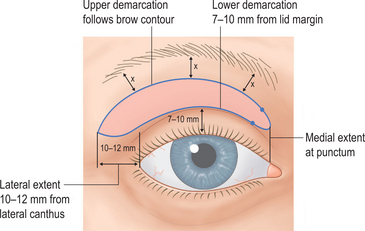

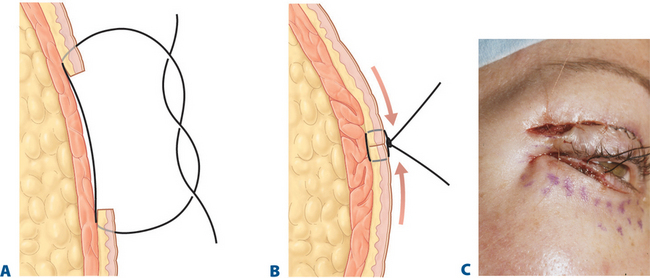

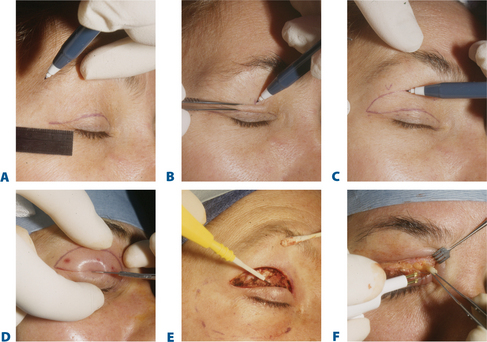

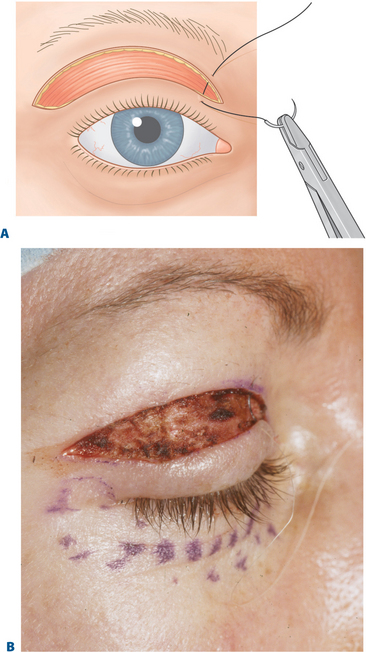

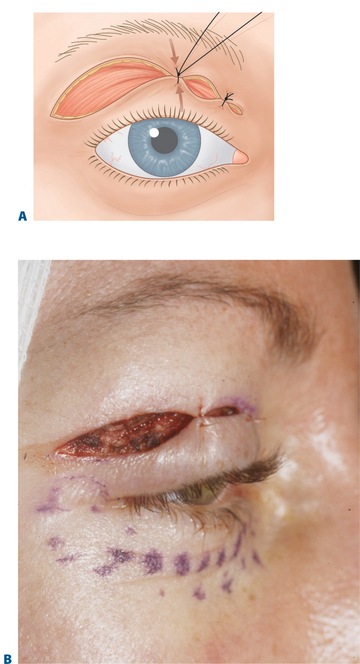

By keeping the crease incision low (i.e. lower portion of upper eyelid crease incision made at 7–10 mm), there is minimal disruption to the majority of the upper eyelid and crease structures (Fig. 8-12). The lower crease incision, as low as 7 mm, is usually reserved for some males or Asian upper eyelid configurations (see Chapter 9), while a majority of patients benefit from eyelid crease incision in the 8–10 mm range. Those individuals with a deep upper eyelid sulcus either from hereditable factors or related to varying degrees of upper blepharoptosis that defer surgical correction of the lid malposition, are most appropriate for the higher 10 mm or more incision. Since there is commonly no advantage to involving the orbicularis oculi muscle, the excision should therefore include skin only (Fig. 8-13B). Although traditionally, a strip of orbicularis muscle at the lower edge of the wound is excised, there is no enhancement of rejuvenative effects with this maneuver. Theoretic reasons for removing orbicularis to effect a scar at the lower skin edge most often results in disturbances in the existing upper eyelid layer attachments that can cause not only unpredicted cicatrizations, but long-term crepeyness of the pretarsal skin. Preservation of orbicularis also adds to upper eyelid volume enhancement by plicating the bulk of orbicularis muscle with approximation of the skin edges by skin closure (Fig. 8-14). This effect can also be more profound, physiologic, and predictable than that which can be accomplished by injecting autologous fat. Enhancing a limited transorbicularis cicatrix (via electrocautery) may be essential for realignment of the eyelid crease at this lower level by effecting adhesions through orbicularis muscle to the dermis at the lower edge of the incision in a more extensive and permanent way then suture fixation. The suborbicularis fibrosis achieved with cautery may be more important for both effecting an adherent relationship between skin–orbicularis, septum, and levator aponeurosis and drawing skin and orbicularis from the eyelid margin to effect a smoother pretarsal surface (Fig. 8-13).

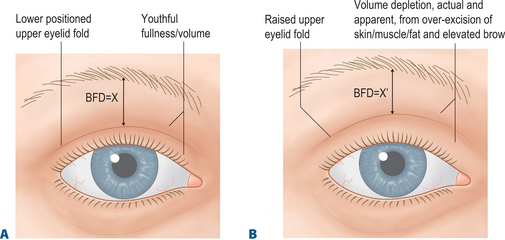

The upper eyelid and eyebrow relationship, I believe, has also been poorly understood in the traditional approaches to upper blepharoplasty. This may be why browplasty has been so freely offered or performed. The youthful upper eyelid fold in most patients is usually quite distant from the eyebrow. This relationship can be dramatically altered with over-excision of upper eyelid soft tissue in traditional blepharoplasty techniques. For instance, with typical skeletonization of the upper eyelid from over-resection of skin and fat with elevating the upper eyelid crease, individuals with even modest brow ptosis would require browplasty in order to achieve greater aesthetics. This would in effect enhance the distance between the upper eyelid fold and the lower brow edge (brow-fold distance/BFD) (Fig. 8-15).16 Could we not accomplish however, in these individuals, a similar and possibly more rejuvenative and physiologically (as well as anatomically) correct effect by these more modern/advanced approaches with upper eyelid aesthetic surgery? In other words, by creating or maintaining the lower positioned upper eyelid crease with appropriate rejuvenative techniques we can achieve the same or improved brow-to-fold distance without the need for browplasty.

Finally, volume considerations of the upper eyelid/brow have been confused or mostly ignored. The deflationary effect afforded by soft tissue shifts and volume loss is what I believe contributes more to the appearance of (pseudo-) excessive upper eyelid skin and eyelid fold changes than do gross changes in brow position or true skin excess. Similarly, although for no apparent aesthetic reason, the concept of excision of ROOF fat has been popularized. I believe that in most situations, there is no reason to cause this unaesthetic volume depletion by direct fat excision and we would fare better by a more physiological approach to the descended fat (i.e. repositioning). The debulking of the lateral upper eyelid orbicularis muscle has also been routinely performed with upper blepharoplasty and yields similar unaesthetic effects. Both of these added steps in upper blepharoplasty further reduce the brow-to-fold distance and thereby may compromise the youthful upper periorbital configuration in many patients. Excision of orbicularis oculi also can add to brow ptosis as remaining functioning orbicularis can now more directly effect brow position with contraction that is reduced or nullified by preserving orbicularis muscle. Enhanced volume can also be effectively regained by autologous fat or hyaluronic acid injection (Fig. 8-7) to this area that can also have illusionary effects of eyebrow position.13

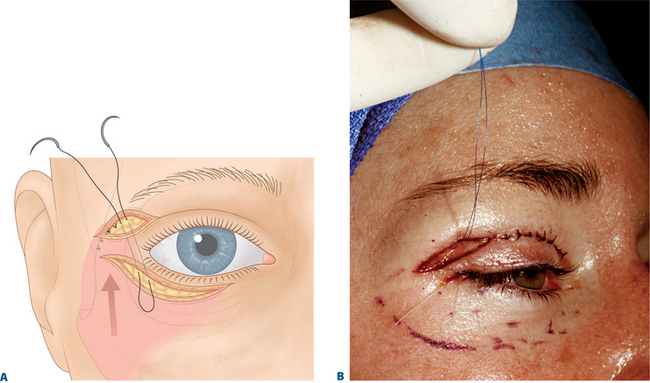

Fixation of the lateral periorbita and prevention of postoperative lateral brow descent can also be afforded by suspension of the lateral orbicularis to the adjacent orbital rim similar to the description by Zarem.17 A browpexy effect is also achieved through creative use of the lateral retinacular suspension4 (Fig. 8-16; see Chapter 15). Volume preservation yields the most aesthetic surgical remedy and combined with effective lateral browpexy achieved with retinacular suspension allows for rejuvenation of the lateral brow, crease, and commissure relationship afforded by enhanced blepharoplasty techniques.

Technique

Results

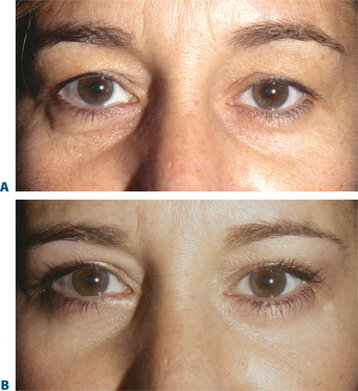

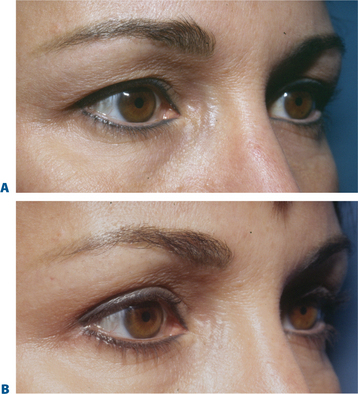

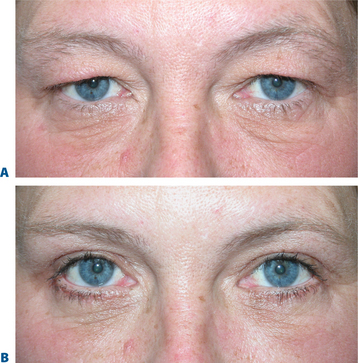

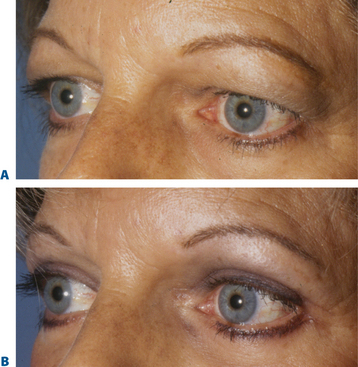

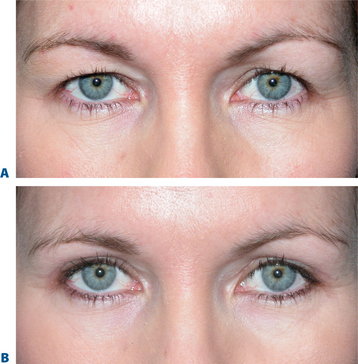

The results using these concepts and techniques for rejuvenation of the upper periorbita are shown in Figures 8-20 to 8-33.

Discussion

Unfortunately, as in many other areas of the face, the traditional approach to upper blepharoplasty has involved over-excessive incision/excision/dissection, disinsertion, and mobilization. This approach had also been customary in traditional browplasty, facelift, canthoplasty, lower blepharoplasty, and blepharoptosis repair. Similar and related results in upper blepharoplasty are thereby encountered, such as an exaggerated postoperative regression from what appears to be an initially satisfactory result. Disappointment may then follow. Over-dissection of the anterior upper eyelid structures (orbicularis, levator aponeurosis, and septum) can result in loss of a tight adherences and conjoined fascial relationships of the anterior lid lamellar structures that are replaced by cicatrix of soft tissue layers that are not normally in contact with each other (skin to septum/tarsus etc.). This sometimes results in loss of normal upper eyelid function (including but not limited to blepharoptosis and lagophthalmos), incarcerative brow descent, late cephalad migration of the upper eyelid crease, irregularity and loss of crispness of the eyelid crease and crepeyness of the pretarsal skin. The illusion of volume depletion can also result by disruption and manipulation of the preaponeurotic fat pad, even when direct excision is avoided. Additionally, excision of orbicularis muscle has other potential detrimental changes including disruption of the deeper structures, the orbital septum and levator aponeurotic insertions. This can also result in a loss of the usual dynamic sliding/gliding14 effects only present in the non-operative or minimally traumatized state that can manifest as problematic cicatricial interface changes such as lagophthalmos or blepharoptosis. Lagophthalmos is usually due to a cicatrix involving the orbital septum. Blepharoptosis is often secondary to either simple levator aponeurotic disinsertion or a limiting mechanical effect from superior migration of the cicatrized orbital septum, orbicularis oculi, or over-excised skin. Disruption or excision of the preaponeurotic fat pad may also have effects on the native cushioned interaction of these multiple and complex soft tissue layers. Some dynamic function of the upper eyelid that could have potential effects on ocular lubrication may be lost. Lastly, whether addressing upper or lower blepharoplasty, the potential adverse effects to patients with borderline or manifest tear deficiencies by altering orbicularis function whether by cicatrization or denervation, must be borne in mind.

Other aesthetic and functional considerations include the seemingly paradoxical effect of enhancing vertical palpebral aperture by extirpating orbital orbicularis. This is as a result of disturbing the antagonist relationship with the levator muscle and subsequent elevation of the upper eyelid margin (that has been also shown with chemodenervation10) as careful analysis of many postoperative photos may reveal an increase in the upper eyelid margin to pupil distance (MRD) of a small but significant proportion. Fortunately, in many instances, this potential effect is probably coincidently nullified by a slight disinsertion or cicatrization (by septum) of the levator aponeurosis with this maneuver. The application of supratarsal fixation, in the traditional sense, utilized these concepts with creation of adherences of the advancing edge of the levator aponeurosis to skin.18–21 On the other hand, the native fascial relationship can be almost entirely preserved or restored (even in situations of significant asymmetry [Fig. 8-21]) by minimal dissection and excision with the added advantage of the improved real or apparent volume.

Finally, aesthetics have been traditionally influenced by trendsetters, sometimes without anatomic basis. A high lid crease and deep upper sulcus may have at one time been the desired aesthetic effect (Fig. 8-1), however currently most fashion/supermodels display a ‘full’ upper eyelid with retained youthful volume and a lower positioned upper eyelid crease. Eyebrows have been traditionally and routinely elevated, in part, to raise the upper eyelid skin fold in keeping with this trend.

Despite these observations, we must consider whether these youthful characteristics are possible and/or appropriate in some individuals. For instance, the elderly female with a dramatic loss of skin elasticity and volume loss of the upper periorbita, individuals with a normally elevated eyelid crease, or those that simply prefer a higher lid fold, may simply be interested in improvement and symmetry rather than reversal. For a host of reasons, true rejuvenation may be difficult and sometimes less preferable, and these individuals may be happier with an elevated eyelid crease with more ‘pretarsal show’ (Figs 8-30, 8-31) than a lower positioned upper eyelid crease.

As in other areas of the face, a prospective analysis of the changes that occur in the upper periorbita and a greater appreciation of the anatomy of facial aging has provided for sound concepts and techniques toward rejuvenation. Precise patient selection and modifications based on presentation will always yield greater aesthetic effects.22

Conclusion

Over 15 years of experience with this technique for upper eyelid aesthetic surgery suggests that this approach best considers the physiologic changes that occur in the aging of this region, and delivers results that are the most rejuvenative, with less stigmata of surgery. The illusion and reality of volume replacement are successfully achieved by surgical methods that are mindful of the necessity of enhancing and preserving the youthful eyelid crease and fullness of the periorbita that has been lacking with traditional excisional methods.

1 Flowers RS. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:331.

2 Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Repair of lower lid deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:417.

3 Glat PM, Jelks GW, Jelks EB, Longaker M. Evolution of the lateral canthoplasty: Techniques and indications. Plast Reconst Surg. 1997;100:1396.

4 Fagien S. Algorithm for canthoplasty. The lateral retinacular suspension: A simplified suture canthopexy. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;103:2042.

5 Fagien S. Lower eyelid rejuvenation via transconjunctival blepharoplasty and lateral retinacular suspension: A simplified suture canthopexy and algorithm for treatment of the anterior lower eyelid lamella. Oper Tech Plast Reconst Surg. 1998;5:121.

6 Hester TR, Codner MA, McCord CD, Nahai F, Giannopoulos A. Evolution of technique of the direct transblepharoplasty approach for the correction of lower lid and midfacial aging: Maximizing results and minimizing complications in a 5-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:393.

7 Carroll RP, Mahanti RL. En bloc resection in upper eyelid blepharoplasty. Ophthal Plast Reconst Surg. 1992;8:47.

8 Perkins SW, Latorre RC. Blepharoplasty: A facial plastic surgeon’s perspective. In: Romo T, Millman AL, editors. Aesthetic Facial Plastic Surgery: A Multidisciplinary Approach. New York: Thieme Medical Publishers Inc.; 2000:262-287.

9 Ramirez OM. Why I prefer the endoscopic forehead lift. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1033.

10 Fagien S. Botox for the treatment of dynamic and hyperkinetic facial lines and furrows: Adjunctive use in facial aesthetic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:791.

11 Lambros V: Restoring the Youthful Upper Eyelid. Panel. The Annual Meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (ASAPS). The New York Hilton; New York, NY. May 5, 2001.

12 Fagien S: Restoring the youthful upper eyelid. Panel. The Annual Meeting of the American Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons (ASAPS). The New York Hilton; New York, NY. May 5, 2001.

13 Lambros V. Fat injection for the aging midface. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;5:129.

14 Siegel RJ. Levator aponeurosis has dynamic insertion. Letter to the editor. Plast and Reconst Surg. 2000;106:735.

15 Putterman AM, Urist MJ. Muller’s muscle-conjunctival resection: Technique for treatment of blepharoptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:619.

16 Fagien S. Eyebrow analysis after blepharoplasty in patients with brow ptosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;8:210.

17 Zarem HA, Resnick JL, Carr RM, Wootton DG. Browpexy: Lateral orbicularis muscle fixation as an adjunct to upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997;100:1258.

18 Siegel RJ. Contemporary upper lid blepharoplasty – tissue invagination. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:239.

19 Flower RS. Upper blepharoplasty by eyelid invagination: Anchor blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:193.

20 Sheen JH. Supra tarsal fixation in upper blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;54:424.

21 Ellenbogen R, Swara N. Correction of asymmetrical eyelids by measured levator adhesion technique. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1982;69:433.

22 Fagien S. Advanced rejuvenative upper blepharoplasty. Enhancing aesthetics of the upper periorbita. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:278.