CHAPTER 9 Upper Blepharoplasty in the Asian Patient

Because the anatomy of the Asian eyelid differs from that of the Caucasian eyelid, I believe that a separate chapter emphasizing the difference is important. In the first edition, I showed how to westernize, or occidentalize, the Asian appearance by constructing an eyelid crease similar to the technique used in Caucasians. It later became apparent that most Asians would like to enhance their appearance by having a crease that conforms with Asian features, and this chapter was added.

Anatomy

Upper eyelids

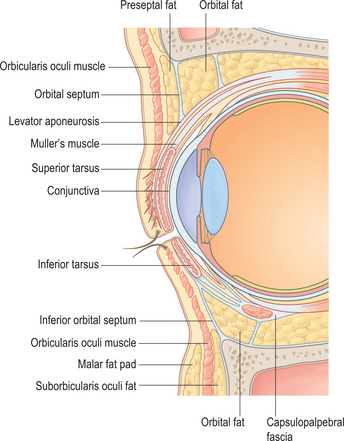

The difference between the Asian and Caucasian eyelid lies at the lower point of fusion of the orbital septum with the levator aponeurosis.1 In Caucasians (Fig. 9-1), the orbital septum fuses with the levator aponeurosis at approximately 8–10 mm above the superior tarsal border, limiting the downward extent of the preapo-neurotic fat pads while allowing the terminal inter-digitations of the aponeurosis to insert toward the subdermal surface of the pretarsal upper eyelid skin, starting along the superior tarsal border and heading inferiorly. As a result, when the levator muscle contracts and pulls the upper eyelid up, the skin forms a crease above the superior tarsal border and the skin above the crease forms the fold.

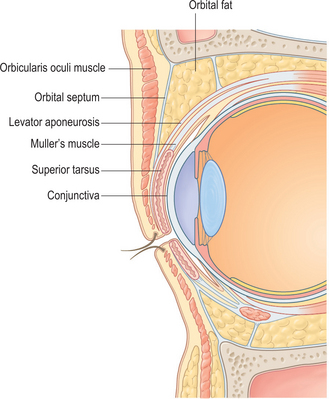

In Asians who do not have this crease (Fig. 9-2), as suggested by the anatomic studies of Doxanas and Anderson,1 the point of attachment of the orbital septum to the levator aponeurosis is lower, frequently as low as the superior tarsal border. This position allows the preaponeurotic fat pads to be present at a lower point on the upper eyelid, giving it a fuller appearance, and is found conjointly with a lack of attachment of the terminal strands of the levator aponeurosis from attaching to the subdermal surface of the pretarsal upper eyelid skin. The result is an apparently puffier ‘single eyelid’ without a crease (Fig. 9-3A).

In terms of fat distribution and compartments, Uchida2 first described the presence of four areas of fat pads in Asian eyelids:

Face

Onizuka and Iwanami3 note that Asians, particularly the Japanese, have a flat face and a head shape that is mesocephalic. The eyes tend not to be recessed deep in the orbit. These authors also find the lateral canthus to be 10 degrees superior to the medial canthus. They believe that creating an upper eyelid crease and removing any upper lid hooding would make the palpebral fissure appear wider and more open, which is aesthetically pleasing. I do not believe that all Asians have a lateral canthus 10 degrees above the medial canthus; however, certainly some of the other observations by these authors may be true.

Eyelid crease

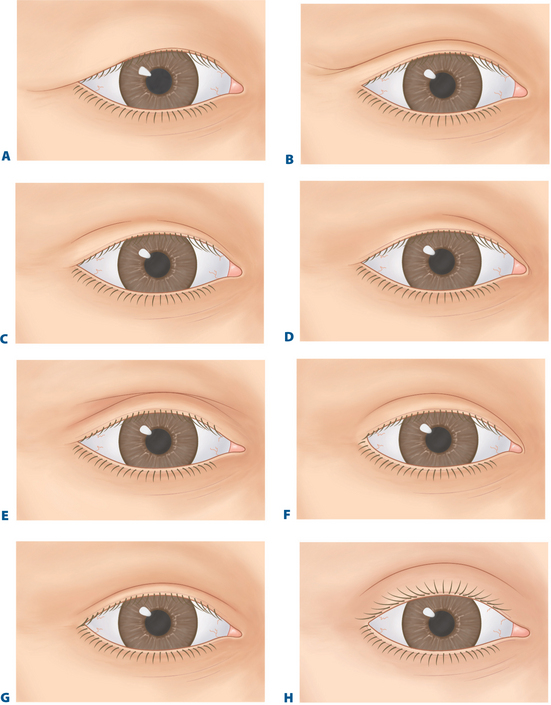

The configuration of the crease in the upper eyelids of Asians varies greatly. As I describe in other publications,4–6 the crease may be absent in one eye (see Fig. 9-3A) and present in the other. It may be continuous (see Fig. 9-3B) or discontinuous (see Fig. 9-3C). The crease may be partial or incomplete (usually present from the medial canthal angle and then fading laterally) (see Fig. 9-3D), and there may be multiple creases on an eyelid (see Fig. 9-3E).

Individuals who have a continuously formed eyelid crease may have either the inside-fold (nasal tapering) type of crease (see Fig. 9-3F) or a crease that is more parallel to the ciliary margin from the medial canthus to the lateral canthus (see Fig. 9-3G). With the inside-fold type, the crease may start from the medial canthal angle and gently flare away from the eyelid margin as it reaches the lateral canthal region (lateral flare) (see Fig. 9-3F); more often, it may start in the medial canthal angle and run fairly parallel to the ciliary margin from the middle of the eyelid onward. Asians rarely have an eyelid crease with a semilunar shape, as in Caucasians, in whom either end of the crease is closer to the respective canthal angle than the central portion of the crease (see Fig. 9-3H).

Preoperative counseling

Most of the patients I encounter know what they want in terms of the crease configuration and its degree of prominence. They may be unaware, however, that swelling accompanies the procedure or that sutures are used. These are important points that need to be addressed with the patient preoperatively.7

Surgical techniques

There are two approaches to the creation of an upper eyelid crease: (1) conjunctival suturing and (2) exter-nal incision. The early champions of the conjunctival suturing technique include Mutou and Mutou,8 Boo-Chai9 who practices external incision as well, and some of the surgeons in Japan. The advantage is that it is a relatively non-invasive technique. The major drawback is that the crease may disappear with time.

Early proponents of the external incision approach include Sayoc10–15 and Fernandez.16 This technique is preferred in the Western Hemisphere and is also practiced in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Conjunctival suturing

In the conjunctival suturing technique, the eyelid is first anesthetized with local infiltration of lidocaine (Xylocaine). The upper eyelid is everted, and three double-armed sutures are placed from the conjunctival side in a subconjunctival fashion above the superior tarsal border. Then either of the two following techniques is performed:

External incision

I favor the external incision technique and perform it as follows.

Marking the eyelid crease

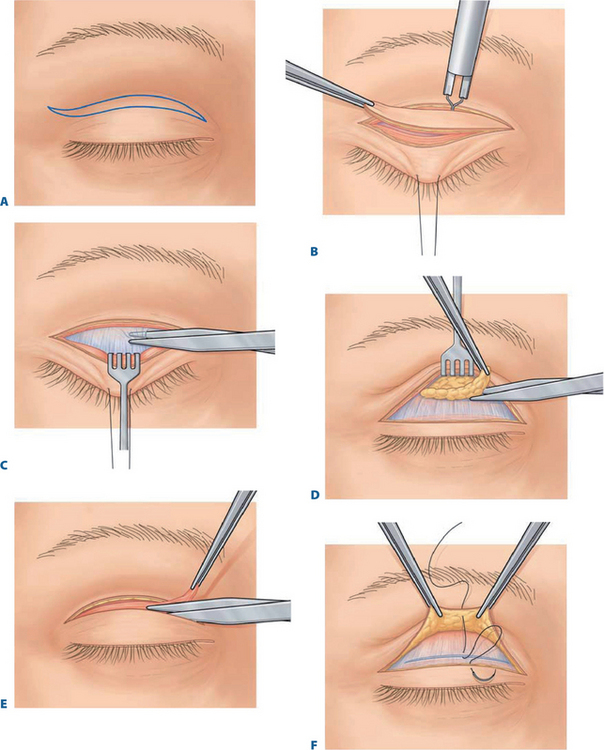

To create adequate adhesions, it is necessary to remove some subdermal tissue. A strip of skin measuring approximately 2 mm is then marked above and parallel to this lower line of incision. Again, in the patient who desires a nasally tapered configuration, I taper this upper line of incision toward the medial canthal angle or merge it with any medial canthal fold that may be present (Fig. 9-4A).

Incision and excision

An incision is then carried out using a No. 15 (Bard-Parker) surgical blade along the upper and lower lines, and I cut just below the subcutaneous plane. Fine capillary oozing is stopped with a delicate bipolar (wet-field) cautery (see Fig. 9-4B). The strip of skin is excised with scissors. The superior tarsal border is still covered by pretarsal and preseptal orbicularis oculi muscle, the terminal portions of the septum orbitale, and the anteriorly directed terminal fibers of the levator aponeurosis behind the septum. Then I retract the incision wound superiorly and use a fine-tipped monopolar cautery in the cutting mode to incise through the orbicularis muscle and orbital septum along the upper skin incision.

In Asians, even though the orbital septum is now only 2–3 mm above the superior tarsal border, it is readily opened, and preaponeurotic fat pads can be seen bulging forward in most cases. The septum is opened horizontally (see Fig. 9-4C), and this strip of preseptal orbicularis muscle and orbital septum hinged along the superior tarsal border is then carefully excised. Depending on the degree of fullness of the upper eyelid, either none or a small amount of the preaponeurotic fat pad is excised with sharp scissors (see Fig. 9-4D). Any bleeding points in the fat pads are controlled with light application of the wet-field cautery. The fat excision often requires a small local supplement of lidocaine in the space beneath the preaponeurotic fat pads. The terminal portion of the levator aponeurosis is now seen along the superior tarsal border. To facilitate the infolding of the surgically created crease, I further excise a 2–3 mm strip of pretarsal orbicularis muscle along the lower skin incision (see Fig. 9-4E).

Skin closure

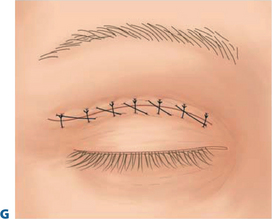

To create adequate adhesion between the terminal portions of the levator aponeurosis above the superior tarsal border to the crease incision lines, I use 6-0 non-absorbable (silk or nylon) sutures to pick up the lower skin edge, the levator aponeurosis along the superior tarsal border, and the upper skin edge and then tie each of these as an interrupted suture (see Fig. 9-4F). Usually, besides the central stitch, two or three sutures are placed medially and two laterally. With these five or six crease-forming sutures in place, the rest of the incision may be closed with 6-0 or 7-0 nylon in a continuous or subcuticular fashion (see Fig. 9-4G).

Patient psychology: postoperative expectations

Postoperatively, the eyelid crease invariably appears high; the patient should again be reminded after the operation that this seeming ‘overcorrection’ is from tissue swelling. I usually inform my patients to expect a certain degree of postoperative edema to last for at least two months and that the crease configuration may vary from month to month and from one eyelid to the other. When the patients are instructed not to expect a stable and satisfactory appearance for 6 months, I find that they are much more accepting of the normal wound-healing process (Fig. 9-5).

Epicanthal folds

Medial canthal folds, as found in Asians, should not be equated to pathologic epicanthal folds as found in congenital blepharophimosis syndrome. The literature includes many articles dealing with this topic.18–29 I tend to be conservative in my treatment and, with few exceptions, refrain from correcting epicanthal folds in Asians, for several reasons:

1 Doxanas MT, Anderson RL. Oriental eyelids: An anatomic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 1984;102:1232-1235.

2 Uchida J. A surgical procedure for blepharoptosis vera and for pseudo-blepharoptosis orientalis. Br J Plast Surg. 1962;15:271-276.

3 Onizuka T, Iwanami M. Blepharoplasty in Japan. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984;8:97-100.

4 Chen WP. Asian blepharoplasty. J Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;3:135-140.

5 Chen WPD. Asian Blepharoplasty and the Eyelid Crease, with DVD (second edition). Philadelphia: Butterworth Heinemann, 2006.

6 Chen WP. Concept of triangular, rectangular and trapezoidal debulking of eyelid tissues: Application in Asian blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1996;97:212-218.

7 Chen WPD, Khan JA, McCord CDJr. Color Atlas of Cosmetic Oculofacial Surgery (Textbook). Edinburgh: Butterworth Heinemann, Elsevier Science, 2004.

8 Mutou Y, Mutou H. Intradermal double eyelid operation and its follow-up results. Br J Plast Surg. 1972;25:285-291.

9 Boo-Chai K. Aesthetic surgery for the oriental. In: Barron JN, Saed MN, editors. Operative Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1980:761-773.

10 Sayoc BT. Plastic reconstruction of the superior palpebral fold. Am J Ophthalmol. 1954;38:556-559.

11 Sayoc BT. Simultaneous construction of the superior palpebral fold and ptosis operation. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41:1040-1043.

12 Sayoc BT. Absence of superior palpebral fold in slit eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;42:298-300.

13 Sayoc BT. Surgical management of unilateral almond eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1961;52:122.

14 Sayoc BT. Anatomic considerations in the plastic construction of a palpebral fold in the full upper eyelid. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;63:155-158.

15 Sayoc BT. Surgery of the oriental eyelid. Clin Plast Surg. 1974;1:157-171.

16 Fernandez LR. Double eyelid operation in the oriental in Hawaii. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1960;25:257-264.

17 Weng CJ, Nordhoff MS. Complication of oriental blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:622-628.

18 Johnson CC. Epicanthus. Am J Ophthalmol. 1968;66:939-946.

19 Verwey A. Der Maskenhafte Antlitz und seine Behandlung. Z Augenheilkd. 1909;22:241.

20 Lessa S, Sebastia R. Epicanthoplasty. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1984;8:159-163.

21 Von Ammon FA. Klinische Darstellungen der Krankheit des Auges und Augenlider. Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann, 1874;443.

22 Von Arlt CF. Erweiterung der Bidspalte Kantoplastik. In: Graef-Saemisch Handbuch des Augenheilkunde. Berlin: G Reimer; 1841.

23 Berger E, Loewy R. Nouveau procédé opératoire pour l’épicanthus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1889;18:453.

24 Mustarde JC. The treatment of ptosis in epicanthal folds. Br J Plast Surg. 1959;12:252.

25 Converse JM, Smith B. Naso-orbital fractures and traumatic deformities of the medial canthus. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1966;38:147.

26 Spaeth EB. Further considerations on the surgical corrections of blepharophimosis (epicanthus). Am J Ophthalmol. 1956;41:61.

27 Spaeth EB. Further considerations on the surgical correction of blepharophimosis and ptosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1964;71:510.

28 Blair VP, Brown JP, Hamm WG. Correction of ptosis in epicanthus. Arch Ophthalmol. 1932;7:831.

29 Matsunaga RS. Westernization of the Asian eyelid. Arch Otolaryngol. 1985;111:149-153.