CHAPTER 10 Upper Blepharoplasty Combined with Levator Aponeurosis Repair*

Defects or stretching of the levator aponeurosis are the most common causes of blepharoptosis seen in patients seeking cosmetic eyelid surgery. Upper eyelid blepharoplasty lends itself well to simultaneous correction of blepharoptosis via repair of aponeurotic defects. Blepharoplasty without correction of a preexisting blepharoptosis may aggravate the blepharoptosis. There are several advantages to the use of a combined procedure:

John R. Burroughs, William M. McLeish and Richard L. Anderson

Evaluation

The preoperative examination entails a thorough review of the physical relationships of the patient’s entire upper face. The heights and contours of the upper eyelids are noted with the forehead and eyebrows in a relaxed, natural position. An asymmetric or heavily furrowed brow often masks the presence of ptosis. Frequently, redundant upper eyelid skin must be gently elevated out of the way to visualize the lid margin and the natural eyelid crease, which is typically elevated by an aponeurosis disinsertion.

Surgical technique

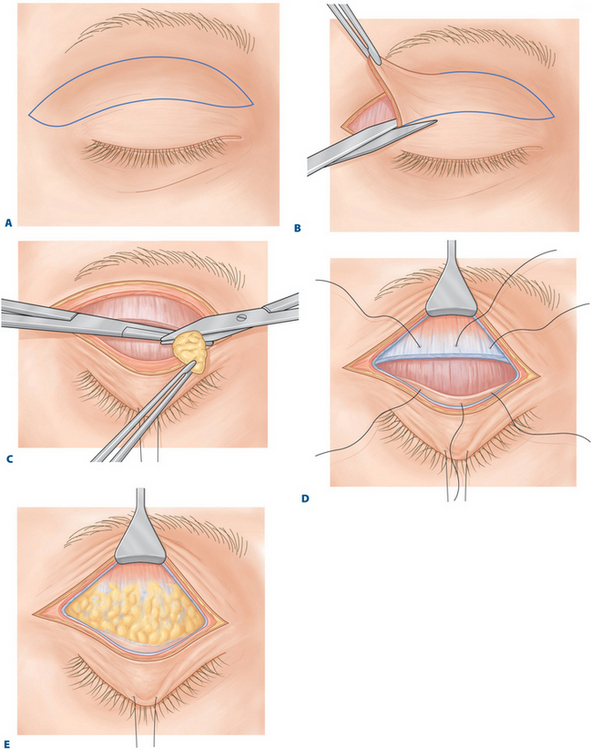

The skin incision is marked superiorly to circumscribe redundant skin and orbicularis muscle tissue. The surgeon establishes the proper amount of skin and muscle that can be safely excised by placing one blade of a smooth forceps on the marked eyelid crease incision and gently pinching sufficient redundant tissue between it and the second blade of the forceps to cause the lid margin to just begin to evert. We use the extra fine point skin marker by ScanlanTM (800-328-9458) as it has an ultra fine tip and allows precise marking. This maneuver is repeated along the length of the eyelid crease incision, and the superior extent of the incision is marked with a pen at each location (Fig. 10-1A). As a general guide, the superior limb of the incision should be at least 10–12 mm below the inferior margin of the eyebrow at the midpupillary position to ensure adequate anterior lamella remains to allow for complete eyelid closure and to prevent iatrogenic brow ptosis.

Figure 10-1 A, Ellipse of upper eyelid skin to be removed is outlined.

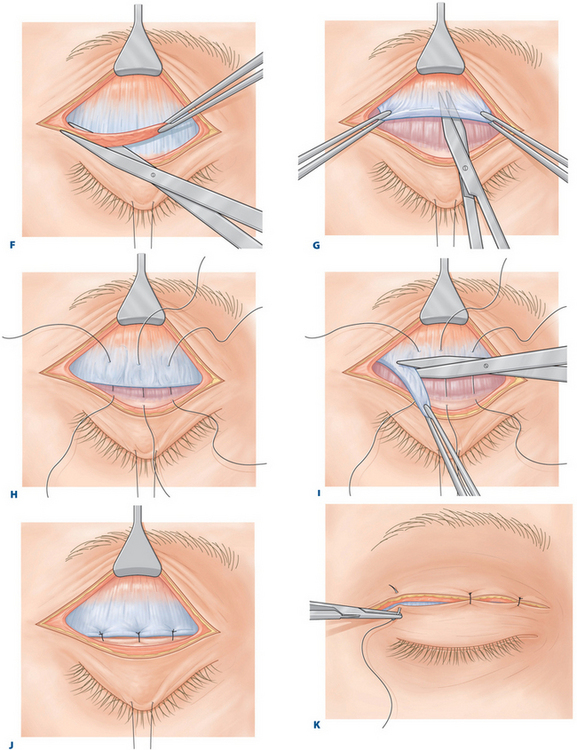

E, Alternative 2: Fatty infiltration of the levator aponeurosis. No distinct disinsertion is noted.

I, Alternative 2: The redundant levator aponeurosis is excised.

After anesthesia is obtained, a 4-0 silk traction suture may be passed through the upper lid margin and secured to the drape below for fixation. The skin incision is made with a No. 15 Bard–Parker or diamond blade. The skin-muscle flap is excised as a single unit with tenotomy scissors or a cutting cautery unit. Elevation of the skin-muscle flap exposes the suborbicular fascia plane and the orbital septum, greatly speeding the dissection and protecting the levator aponeurosis from iatrogenic damage (Fig. 10-1B). Hemostasis is controlled with bipolar cautery. We have found the non-stick SILVERGlideTM (800-259-6156) bayonet electrocautery forceps allow rapid cauterization of large areas without the need to frequently re-clean the tips during cauterization of multiple sites of bleeding.

The medial fat pocket is more extensive than the central pocket. It can be discerned from the medial compartment by its whiter coloration, thicker or denser consistency, and greater vascularity. Frequently, sharp lysis of normally occurring fibrous septa is required before the fat in this compartment presents itself. Gentle retropulsion of the globe further enhances delivery of the fat. Hemostasis is particularly important in this region because the medial fat pad contains terminal branches of the ophthalmic artery and multiple large-caliber veins. Bleeding from these vessels can be significant and, if inadequately controlled, can result in vision-threatening orbital hemorrhage.1 Furthermore, blind cautery in this area can lead to damage to the trochlea and to subsequent diplopia.2 For these reasons, we advocate care to not excise too much fat from the medial and central fat pockets because this can create a depression and hollowed appearance (Fig. 10-1C). Aggressive inferior dissection in this area can damage the medial horn of the levator aponeurosis, aggravating ptosis and ‘lateralization’ of the tarsal plate, as described by Shore and McCord.3

Temporally, the position of the lacrimal gland should be noted. A prolapsing lacrimal gland creates fullness in this area, which can masquerade as fat prolapse and even temporal brow ptosis.4 A prolapsed lacrimal gland needs to be repositioned within the lacrimal gland fossa. One should avoid the temptation to excise the gland, which will result in diminished aqueous tear production and dry eye symptoms.

With the appropriate preaponeurotic fat now removed, the underlying aponeurosis is visualized. Rarely, a distinct disinsertion between the tarsus and the leading edge of the aponeurosis is encountered (Fig. 10-1D). This is easily recognized because the peripheral arcade running through Müller’s muscle just above the superior border of the tarsal plate is clearly visible. More commonly a rarefied and stretched aponeurosis or an aponeurosis with extensive fatty infiltration is found (Fig. 10-1E).

The needle is then regrasped and passed through the disinserted edge of the levator aponeurosis (see Fig. 10-1D). No attempt is made to dissect the strongly adherent and vascular Müller’s muscle off the undersurface of the aponeurosis. Any bleeding is im-mediately controlled with a bipolar cautery to avoid creating a hematoma in Müller’s muscle, which can complicate adjustment of the eyelid height and contour. The suture is permanently tied. All subsequent suture passes between the aponeurosis and the tarsus will also be permanently secured at the time of the procedure. Other surgeons have advocated the use of temporarily tied, adjustable aponeurotic sutures, which can be manipulated during the perioperative period to alter the eyelid height as needed.5 We have found these sutures to be awkward to use; more importantly, they have not improved our results over spreading the incision apart and removing the deep suture if overcorrected in the 1–2 week postoperative period.

With the central suture permanently set, the patient is asked to open his or her eyes, and the height of the eyelid is examined with reference to the superior limbus and the height of the contralateral eyelid. If the height of the eyelid margin appears appropriate, the patient may be placed in the sitting position and the eyelid height is reconfirmed if another check is desired. An eyelid height 1–2 mm higher than the intended final position is usually ideal because the eyelid will settle as the effects of the epinephrine dissipate and orbicularis function returns. If the eyelid height is undercorrected, the suture is removed and repositioned higher on the aponeurosis.

Once the desired height is achieved additional sutures may be passed in an identical manner at the temporal and nasal limbal positions (see Fig. 10-1D). Oftentimes, excellent eyelid height and contour may be achieved with only a single suture pass. The temporal suture if used should be undercorrected to avoid temporal flare as temporal overcorrection is a frequent complication of surgeons just beginning with aponeurotic repair. Temporal suture placement is seldom used in our practice except in congenital cases or decreased levator function. Again, the height and contour of the eyelid are reassessed in up and downgaze.

When an attenuated aponeurosis is still attached to the tarsus in blepharoptosis cases a thin strip of pre-tarsal orbicularis muscle and attenuated aponeurosis is excised along the superior border of the tarsal plate (Fig. 10-1F). This maneuver bares the superior border of the tarsal plate of the soft tissue and the aponeurotic adhesions and freshens the edge of the aponeurosis, which will ensure solid refixation. This step may result in the lowering of the eyelid crease as already discussed. The 5-0 polyglactin sutures are passed through the tarsal plate in the manner previously described and are then passed through and above the leading edge of the aponeurosis. The amount of levator advancement and resection is determined by eyelid positioning as previously discussed.

If more than 4 mm of aponeurotic advancement is required, the aponeurosis is sharply dissected off the underlying Müller’s muscle to the desired level, and the redundant aponeurosis is excised (Fig. 10-1, G–I). No attempt is made to resect Müller’s muscle. The lid height is again checked with the patient in both up and downgaze. If there is any question about the desired height of the eyelid, it is always safest to err on the side of overcorrection, as this can easily be corrected postoperatively. Once the appropriate eyelid height is reached, the temporal and nasal sutures may be placed if necessary (Fig. 10-1, H–J).

The blepharoplasty incision is closed with 6-0 plain gut sutures (Fig. 10-1K). These sutures dissolve in 10–14 days, eliminating the need for suture removal. Interrupted sutures are preferred because they produce better wound apposition and allow egress of postoperative wound fluid. Only the skin layer is closed. The septum should never be incorporated into the closure because doing so could result in postoperative lagophthalmos. A redundant medial skin fold or ‘dog ear’ can he excised in a triangular fashion. Because the orbital septum is fully opened and the redundant preaponeurotic fat is sharply excised in addition to removal of a strip of pretarsal orbicularis muscle, a strong eyelid crease is achieved without the need for supratarsal fixation sutures. We generally avoid the use of supratarsal fixation sutures, as they have been associated with recurrent ptosis, epithelial inclusion cysts, suture abscesses, and asymmetric eyelid creases.

Adjunctive procedures

Many of the patients presenting to us for ‘droopy’ eyelids have a component of both blepharoptosis and dermatochalasis. We therefore highly advise our patients to have both elements addressed. Even if the major problem is ptosis, we will usually remove an appropriate amount of any excess skin and find that a wide, typical upper blepharoplasty incision to be cosmetically superior to smaller incision techniques. Adjunctive procedures that we often perform through the typical upper blepharoplasty incision include internal brow elevation, glabellar furrow reduction, and lateral canthopexy.6 We strongly encourage internal brow elevation for any patient who has less than 10 mm of skin between the upper eyelid crease and the inferior brow cilia and are not interested in more aggressive brow elevation. It is ideal for heavy ptotic brow fat pads. This procedure involves the sculpting of the brow fat pads, and release of the orbital ligament in the upper eyelids. The glabellar furrows may effectively be reduced by partially resecting the corrugator and depressor superciliaris muscles through the upper blepharoplasty incision, which gives a permanent Botox®-like effect and has been very useful for those with headaches in this area.7

Postoperative care

Postoperatively, the patient is instructed to apply cold compresses to the eyelids for 2 days and to place lubricating drops and ointment in the eyes for several days to weeks until eyelid closure becomes complete. A mild to moderate amount of temporary lagophthalmos is expected postoperatively. Postoperative edema usually clears in 2–4 weeks, but if necessary a Medrol dose pack often helps in more severe cases. We have also found arnica montana and vitamin C to reduce postoperative bruising and hasten resolution.

Treatment of overcorrection and undercorrection

Overcorrection

Postoperative management of lid height asymmetry is relatively simple with the external aponeurotic ptosis repair and can usually be performed in the office.8 Small overcorrections generally respond to gentle massage of the eyelid for 5–10 minutes four times a day. To accomplish this, we have the patient hold his or her eyebrow up with one hand while pushing the eyelid both down and in with the index finger of the other hand. This massage can begin as soon as the skin incisions have healed.

Results

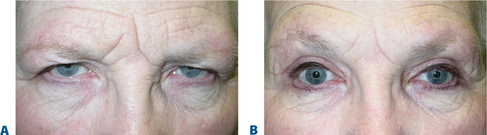

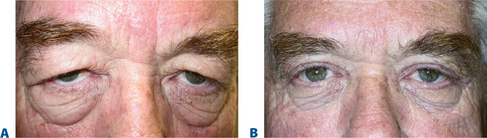

The combined upper eyelid blepharoplasty and external levator aponeurotic ptosis repair procedure has been performed in over 3000 patients over the past three decades (Figs 10-2 and 10-3). Good to excellent results, as determined by symmetric lid contour and central lid height within 1 mm of the desired position, were achieved with a single procedure in over 90 percent of patients.

Primary overcorrections requiring removal of aponeurotic sutures in the office occurred in less than 2 percent of patients; all instances were successfully corrected. Primary undercorrections were noted in fewer than 3 percent of patients. Some of these patients required a second procedure with more aggressive aponeurotic advancement. Late blepharoptosis recurrence (occurring more than 6 months following the initial procedure) was seen in less than 1 percent of patients. Most of these recurrences were in patients noted to have fatty infiltration of the aponeurosis at the initial procedure. At the time of the second operation, most of these patients were found to have attenuation of the aponeurosis immediately above the tarsal plate or increased degeneration and fatty infiltration. Very few true disinsertions were encountered. Presumably, the levator aponeurosis in this group of patients is inherently weak and prone to stretching and future degeneration.

1 Anderson RL, Edwards JJ, Wood JR. Bilateral visual loss after blepharoplasty. Ann Plast Surg. 1980;5:288-292.

2 Wesley RE, Pollard ZF, McCord CD. Superior oblique palsy after blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;66:283-287.

3 Shore JW, McCord CD. Anatomic changes in involutional blepharoptosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1984;98:211-227.

4 Smith B, Petrelli R. Surgical repair of prolapsed lacrimal glands. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:113-114.

5 Collins JR, O’Donnell BA. Adjustable sutures in eyelid surgery for ptosis and lid retraction. Br J Ophthalmol. 1994;78:167-174.

6 Burroughs JR, Bearden WH, Anderson RL, McCann JD. Internal brow elevation at blepharoplasty. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:36-41.

7 Bearden WH, Anderson RL. Corrugator superciliaris muscle excision for tension and migraine headaches. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;21:418-422.

8 Jordan DR, Anderson RL. A simple procedure for adjusting eyelid position after aponeurotic ptosis surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:1288-1291.