CHAPTER 4 Unusual and Problematic Types of Breast Cancers: DCIS, Intracystic Papillary Carcinoma, Benign-appearing Breast Cancers, ILC, Inflammatory Breast Cancer, and Breast Cancer in Implant Patients

Certain subtypes of breast cancer can be particularly challenging to detect on routine mammography. This can have implications for staging and surgical outcomes.1 Although the use of supplemental imaging tools, such as ultrasound and MRI, help to improve cancer detection and delineation of the extent of disease,2 cancers such as invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) and ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) continue to be problematic. Other generally readily detected carcinomas, such as medullary, papillary, and mucinous (colloid), may be difficult to recognize as malignant because of their propensity for relatively benign-appearing morphologic features.

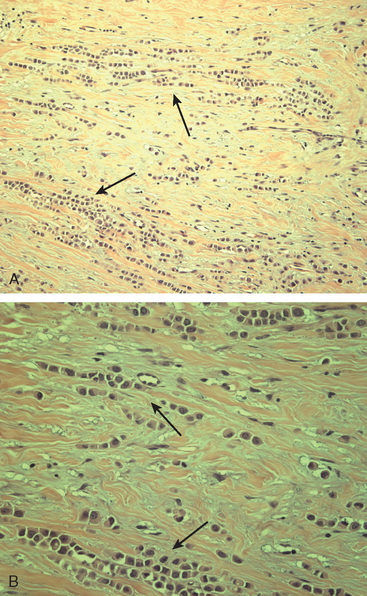

Although ILC represents only about 10% of all breast tumors,3 it is known to be one of the most common reasons for a false-negative mammogram.4 The infiltrating growth pattern of single-file strands of malignant cells, often with minimal fibrotic reaction, is one of the reasons that ILC can be difficult to detect (Figure 1). In addition, if an ILC does produce a mammographically detectable finding, it may not form a mass and may be of relatively low or equal density to normal fibroglandular tissue.3 Even large lesions may still be occult on mammography.5 Mammographic sensitivity for ILC ranges between 57% and 89%.4–8 In addition, ILC has a higher propensity for multifocal and bilateral involvement. Its extent is often underestimated by mammography.9,10 Understaging can significantly affect surgical outcomes and patient treatment. MRI has been shown to be useful in better defining the extent of disease in patients with ILC.10,11

The increasing use of screening mammography has led to an increase in the detection of DCIS, usually presenting as clustered microcalcifications. However, establishing the extent of disease can be problematic because DCIS is commonly multifocal and is often noncalcified. A recent study suggested that MRI may be more useful in detecting DCIS than previously thought.12

Mucinous carcinoma, also termed colloid carcinoma, is relatively uncommon.13 Because it often presents as a circumscribed mass, it may potentially be misinterpreted as a benign lesion, such as a fibroadenoma. However, close inspection usually reveals features that should distinguish mucinous carcinoma from benign entities, such as marginal irregularity or heterogeneous echotexture on ultrasound. In a similar manner, medullary carcinoma can present as a well-circumscribed mass. Medullary carcinomas account for about 3% to 5% of breast cancers and have a prognosis that is generally better than more common types of invasive breast cancer.

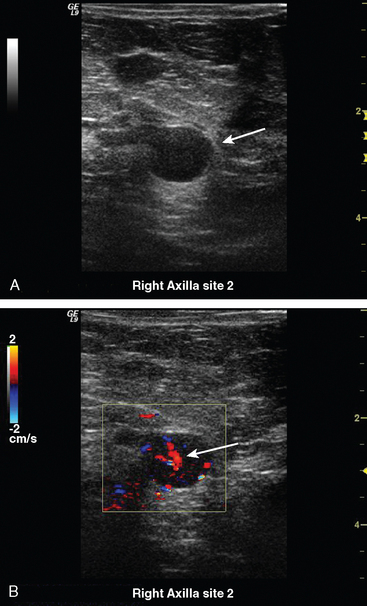

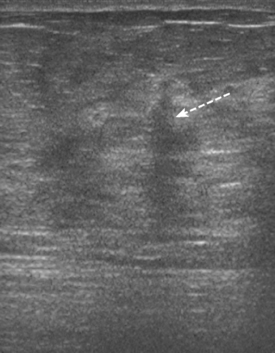

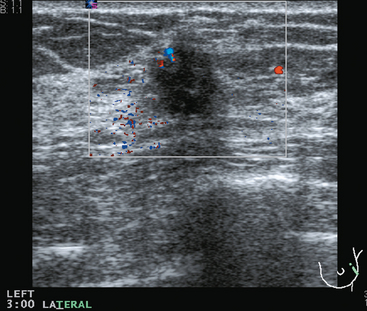

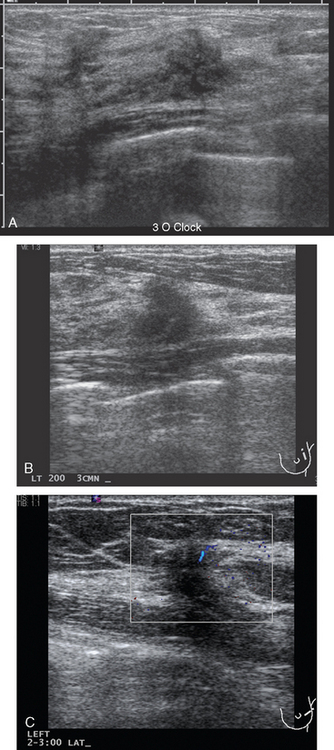

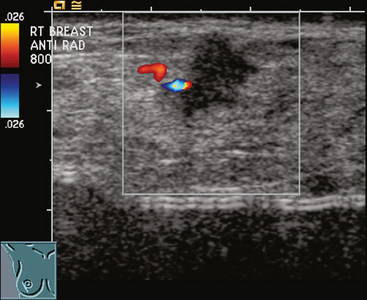

Some carcinomas may have features on ultrasound that could be confused with benign entities. Purely hyperechoic lesions on ultrasound, such as a lipoma, are invariably benign. However, some invasive carcinomas may have a hyperechoic halo that may simulate a benign lesion. On close inspection, a hypoechoic “nidus” or central region is generally present to distinguish carcinomas from completely hyperechoic benign lesions. Some carcinomas, particularly high-grade cancers and metastatic lymph nodes, may be extremely hypoechoic on ultrasound and could be mistaken for anechoic cysts. In addition to proper gain settings and margin analysis, color Doppler helps in distinguishing solid masses from cysts (Figure 2).

1 Veltman J, Boetes C, van Die L, et al. Mammographic detection and staging of invasive lobular carcinoma. Clin Imaging. 2006;30(2):94-98.

2 Berg WA, Gutierrez L, NessAiver MS, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of mammography, clinical examination, US, and MR imaging in preoperative assessment of breast cancer. Radiology. 2004;233(3):830-849.

3 Newstead GM, Baute PB, Toth HK. Invasive lobular and ductal carcinoma: mammographic findings and stage at diagnosis. Radiology. 1992;184(3):623-627.

4 Krecke KN, Gisvold JJ. Invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast: mammographic findings and extent of disease at diagnosis in 184 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;161(5):957-960.

5 Holland R, Hendriks JH, Mravunac M. Mammographically occult breast cancer: a pathologic and radiologic study. Cancer. 1983;52(10):1810-1819.

6 Hilleren DJ, Andersson IT, Lindholm K, Linnell FS. Invasive lobular carcinoma: mammographic findings in a 10-year experience. Radiology. 1991;178(1):149-154.

7 Paramagul CP, Helvie MA, Adler DD. Invasive lobular carcinoma: sonographic appearance and role of sonography in improving diagnostic sensitivity. Radiology. 1995;195(1):231-234.

8 Le Gal M, Ollivier L, Asselain B, et al. Mammographic features of 455 invasive lobular carcinomas. Radiology. 1992;185(3):705-708.

9 Lee JSY, Grant CS, Donohue JH, et al. Arguments against routine contralateral mastectomy or undirected biopsy for invasive lobular breast cancer. Surgery. 1995;118:640-648.

10 Boetes C, Veltman J, van Die L, et al. The role of MRI in invasive lobular carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;86(1):31-37.

11 Mann RM, Veltman J, Barentsz JO, et al. The value of MRI compared to mammography in the assessment of tumour extent in invasive lobular carcinoma of the breast. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34(2):135-142. Epub 2007 Jun 15.

12 Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Bieling HB, et al. MRI for diagnosis of pure ductal carcinoma in situ: a prospective observational study. Lancet. 2007;370(9586):485-492.

13 Dhillon R, Depree P, Metcalf C, Wylie E. Screen-detected mucinous breast carcinoma: potential for delayed diagnosis. Clin Radiol. 2006;61(5):423-430.

CASE 1 DCIS, calcified and noncalcified

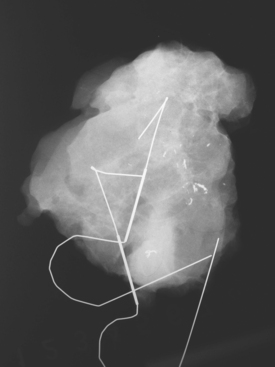

A 50-year-old woman was found on screening mammography to have suspicious pleomorphic microcalcifications in the 12-o’clock position of the right breast (Figure 1). Biopsy was performed with stereotactic technique, confirming intermediate-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) (Figure 2). There was a family history of breast cancer, most notably in a sister at age 31.

Breast MRI was obtained to evaluate for occult invasive components and extent of disease. Ultrasound had not shown an associated mass. The breast MRI showed clumped, small masses of intense enhancement with washout at the expected level of the residual known DCIS (Figures 3 and 4). There was a second, separate site of concerning, clumped enhancement in the same breast, with plateauing enhancement, thought suspicious for possible additional, noncalcified DCIS. MRI-guided biopsy was performed, and pathology showed two tiny foci of high-grade DCIS, the largest 1 mm in size. A clip was placed to mark the MRI-guided biopsy site, and postbiopsy mammography confirmed it to be removed in location from the remaining microcalcifications (Figure 5).

These evaluations showed the patient had proven multicentric DCIS, including noncalcified DCIS. She was recommended to have a mastectomy but was strongly desirous of breast conservation. Accordingly, lumpectomies were performed after a triple-needle localization, in which the remaining microcalcifications at 12 o’clock were bracketed with two needles (Figure 6), and the clip at 9 to 10 o’clock from the MRI-guided biopsy was separately localized (Figure 7). The specimen at 12 o’clock contained both of the bracketing localization wires and the remaining pleomorphic microcalcifications. These were noted to approach a margin, from which additional tissue was obtained. The initial specimen from the 9- to 10-o’clock localization showed the hook wire, but not the MRI-placed clip. The surgeon was advised of this, additional tissue was obtained and radiographed, and the clip was found in the second specimen (Figure 8).

Mastectomy was again recommended for this patient, who desired re-excision and breast conservation. The 12-o’clock lumpectomy site was re-excised. The re-excised lateral margin showed three microscopic foci of high-grade DCIS (largest, 0.5 cm), two of which were closer than 2 mm to the new lateral margin. The new inferior margin was clear, and this specimen showed a single microscopic focus of DCIS. The additional deep margin excision showed three foci of invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) (largest, 0.4 cm), with multifocal high-grade DCIS involving greater than 50% of the lesion (extensive intraductal component), DCIS focally at the new deep margin, and multiple foci of DCIS and IDC closer than 2 mm to the new deep margin.

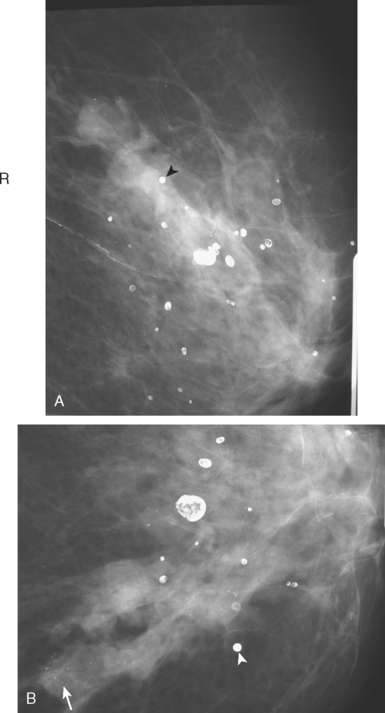

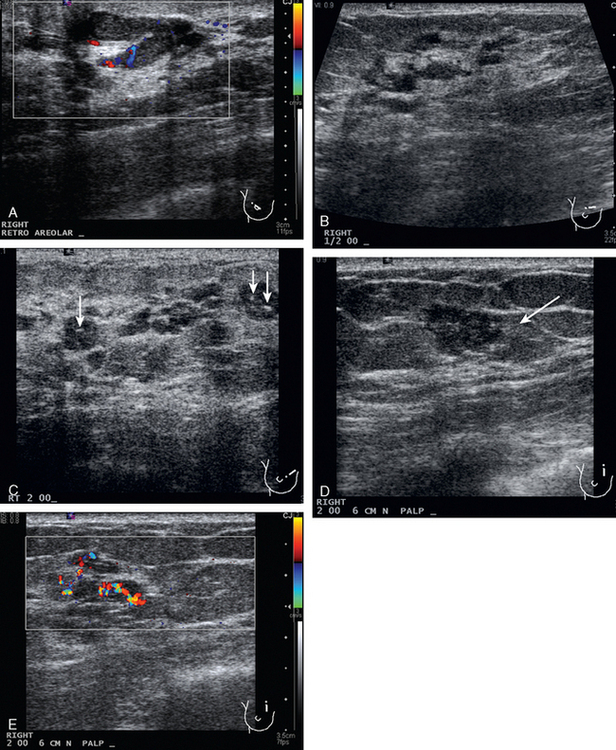

CASE 2 Extensive intraductal carcinoma presenting as a palpable, tumor-filled ductal system

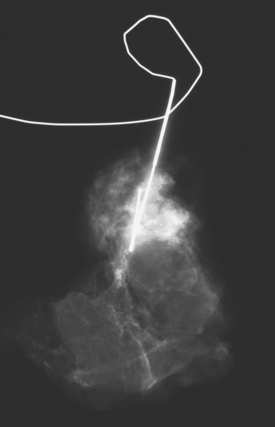

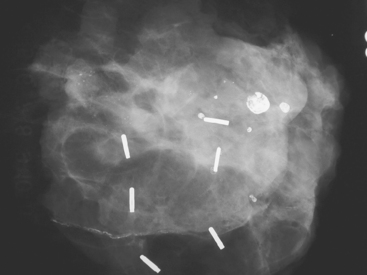

A 74-year-old woman was evaluated for right upper inner quadrant (UIQ) palpable firmness. Mammography showed a segmental region of tubular nodularity with suspicious microcalcifications, spanning 5 cm, extending from the retroareolar region to the UIQ (Figures 1 and 2). On ultrasound, dilated retroareolar soft tissue containing ducts extended into the UIQ (Figure 3). Ultrasound-guided biopsy obtained intermediate-grade intraductal carcinoma with papillary and cribriform features. The patient was a part-time resident of the area and had multiple medical problems, including severe atherosclerotic disease with prior coronary artery bypass graft, stents, and abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. She elected treatment with partial mastectomy and interstitial brachytherapy (Figure 4).

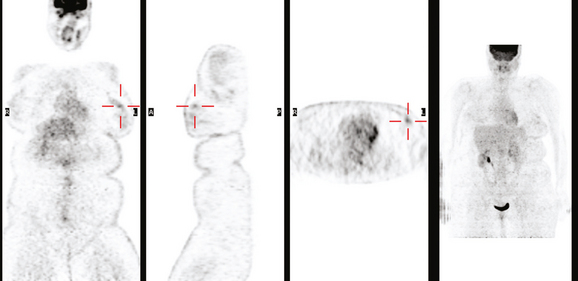

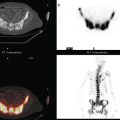

CASE 3 BRCA1 patient, abnormal whole-body PET leading to diagnosis of DCIS

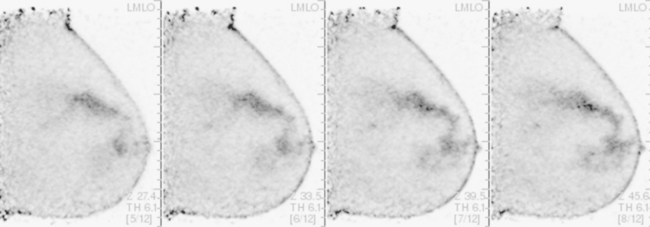

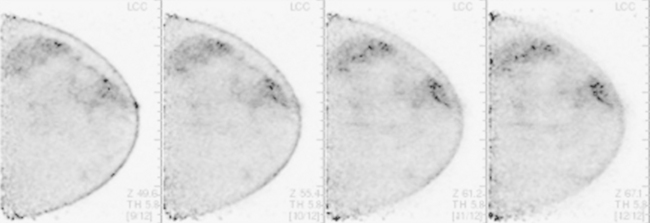

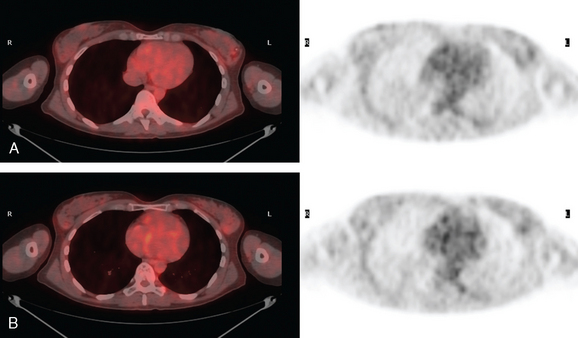

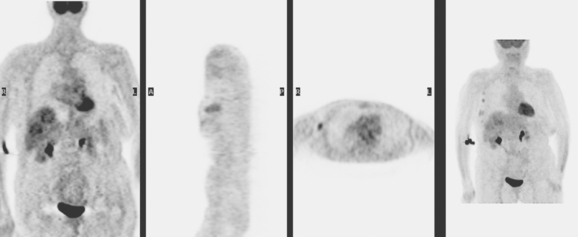

A 53-year-old woman with a past medical history of right breast cancer 15 years before and ovarian cancer 5 years previous, underwent positron emission tomography (PET)/CT for surveillance of ovarian cancer. Her prior breast cancer was infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), which had been treated with lumpectomy and radiation. Whole-body PET/CT showed asymmetrical, relatively focal, mildly increased uptake in the left lateral breast (Figure 1). Correlation with a recent mammogram showed no corresponding abnormality. Left breast ultrasound was also negative.

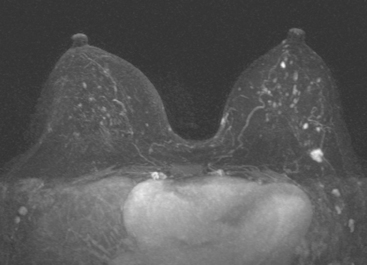

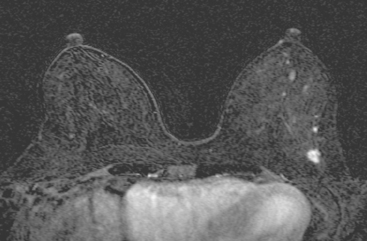

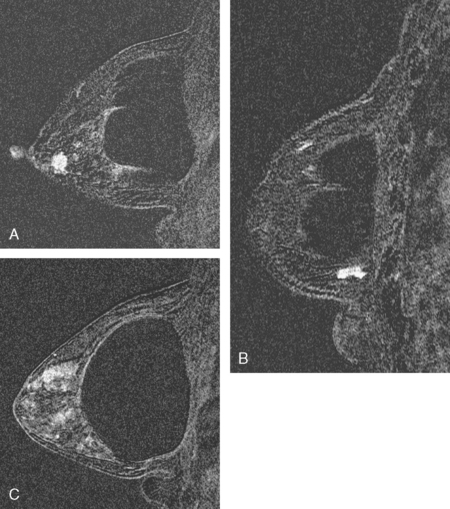

Breast MRI was obtained 6 months later. Segmental, clumped, plateauing enhancement was found in the left lateral breast (Figures 2, 3, and 4). A positron emission mammography (PEM) scan with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) was obtained as well (Figures 5 and 6).

MRI-guided biopsy was performed (Figure 7). Pathology showed high-grade ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), with comedonecrosis and cribriform types, and lobular cancerization and multiple foci suspicious for microinvasion. The tumor was estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative.

TEACHING POINTS

The patient’s high-grade DCIS was picked up as an unsuspected finding on whole-body PET scan, obtained for surveillance for ovarian cancer. Initial workup with mammography and sonography showed no correlate. Breast MRI is the appropriate next breast imaging step in the evaluation, given the patient’s high risk profile and the unexplained PET scan finding.

As of this writing, PEM devices have only recently become available and are limited in distribution. There is little collective experience with the capabilities and limitations of PEM scanning. A multicenter prospective trial comparing the performance of PEM to breast MRI in preoperative staging of newly diagnosed breast cancers is accruing patients, and data from this trial will hopefully help in delineating the appropriate role of PEM in the breast imaging armamentarium.

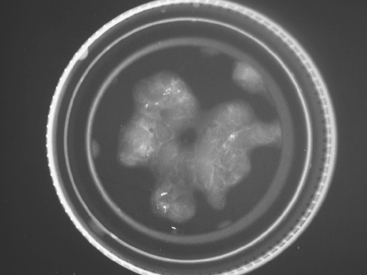

CASE 4 Intracystic papillary carcinoma

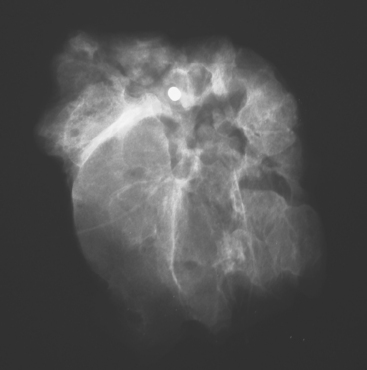

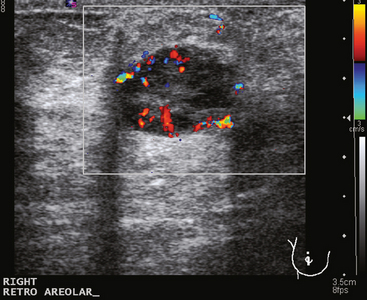

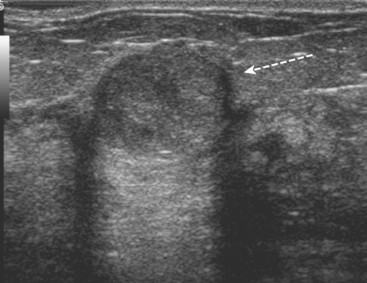

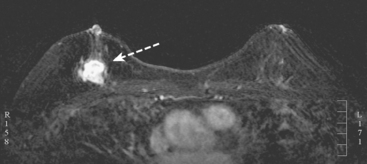

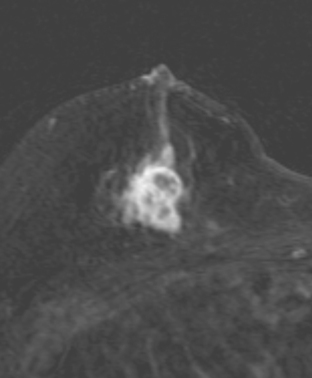

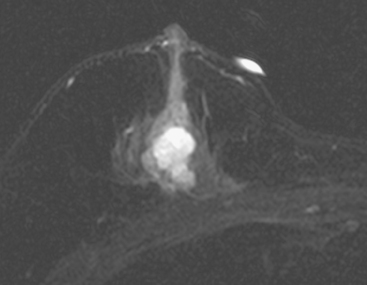

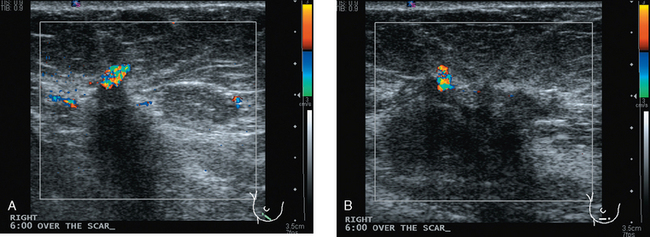

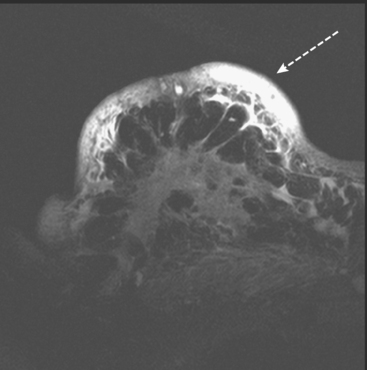

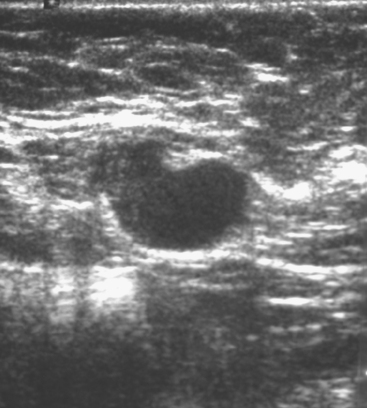

A 51-year-old woman underwent breast imaging evaluation for a clear right nipple discharge. Two years before, she was diagnosed with right breast intracystic papillary neoplasm, estrogen receptor positive (Figure 1), and treated with lumpectomy only. On physical examination, a serous fluid discharge could be readily elicited by palpation of the right lateral breast, in the region of her surgical scar. No clear imaging correlate could be identified on diagnostic mammography or breast ultrasound, with scarring noted on ultrasound at the lumpectomy site (Figure 2). Breast MRI was obtained and showed an unusual focus of branched, linear right retroareolar enhancement, with washout (Figures 3 and 4). A second focus of abnormal mass enhancement measuring 8 mm was identified, at the 9-o’clock right breast posterolateral level, with washout (Figure 5). MRI-guided biopsy was performed of the retroareolar branched enhancement, identifying intracystic papillary carcinoma, considered in situ, with no invasion identified. The second site was too posterior to reach with a grid MRI-localizing device. A second breast ultrasound was performed to find a correlate for the posterior MRI abnormality (Figure 6). A 6-mm hypoechoic nodule was identified on ultrasound at 10 o’clock, thought to be the probable correlate for the MRI finding. This had not been noted on a prior right breast ultrasound, obtained before the MRI. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy identified low-grade, cribriform ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), similar in histology to the patient’s prior specimens.

With two proven sites of right breast intracystic papillary carcinoma (IPC)/DCIS, the patient was treated with modified radical mastectomy. She elected to undergo prophylactic mastectomy on the left at the same time, with immediate reconstruction with tissue expanders. On the right, one sentinel and one additional lymph node were negative. The right mastectomy specimen showed focal residual intracystic papillary carcinoma and focal low-grade micropapillary DCIS at the subareolar level. The left prophylactic mastectomy specimen was negative.

An additional example of this less common histology is illustrated in Figure 7.

TEACHING POINTS

This patient’s original IPC shows typical imaging features of these rare lesions, with a complex cyst with septations and solid components. These lesions can vary in appearance from predominantly cystic (often complex, with septations and mural nodules, as here) to predominantly solid (another example, different patient, Figure 7).

Associated DCIS or invasive cancer is found 40% of the time, and there is potential for axillary nodal involvement. These tumors are often estrogen receptor positive. The prognosis for IPC without DCIS or infiltrating ductal carcinoma is excellent. No influence on recurrence or survival using radiation therapy has been demonstrated.

CASE 5 Colloid cancer, two cases

A 46-year-old woman, with a known left breast sarcoma history, underwent preoperative bilateral MRI. The MRI demonstrated a previously unknown mass in the contralateral breast (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Ultrasound identified a solid corresponding mass in the lower outer right breast (Figure 5). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy diagnosed an invasive mucinous carcinoma. The patient was treated with bilateral lumpectomies and radiation therapy.

TEACHING POINTS

This case is an example of a mucinous carcinoma, also termed colloid carcinoma, which consists of tumor cells floating within pools of mucin. On imaging, mucinous carcinomas potentially can be misinterpreted as benign. Features suggestive of benignity illustrated by this lesion include relatively well circumscribed margins, high T2 signal on MRI, and posterior acoustic through-transmission on ultrasound. However, detailed examination helps to prevent confusing this lesion for a fibroadenoma. Close inspection of both the MRI and the ultrasound shows that the margins of the mass are not as well circumscribed as expected for a fibroadenoma. In addition, unlike classic fibroadenomas, the internal architecture of this mucinous carcinoma is heterogeneous on both the MRI and ultrasound. Mammographically, mucinous carcinomas often present as wellcircumscribed, relatively low-density masses, which may delay their diagnosis. Pure mucinous carcinoma is an uncommon form of breast malignancy, accounting for 1% to 2% of all breast cancers. They tend to occur in older patients. In contrast to mixed mucinous carcinomas, pure mucinous carcinomas have a favorable prognosis, are often low-grade tumors, and rarely metastasize.

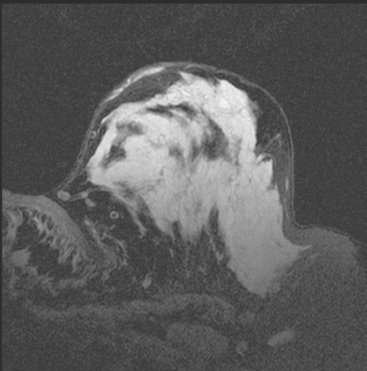

Not every colloid carcinoma is as innocent in appearance as this example. Another case of an invasive mucinous carcinoma, in a 72-year-old woman with a palpable right breast mass, also shows bright signal on T2-weighted MRI, but other features of malignancy are notable (Figures 6, 7, 8, and 9).

TEACHING POINTS

This case demonstrates a less benign imaging appearance of a mucinous carcinoma than the preceding case. The bright signal on T2-weighted sequences might lead one to consider a fibroadenoma in the imaging differential diagnosis. However, the heterogeneity of the enhancement, with rim and internal septation enhancement, and the marginal irregularity, are features highly suggestive of malignancy. As always in breast imaging, a lesion should be judged by the most sinister feature it displays, and one should not be reassured by other, more typically benign characteristics.

CASE 6 Medullary cancer, question of liver metastases on breast MRI; FDG uptake on PET in a fibroid

A 48-year-old premenopausal female noted a palpable left breast lump she had never identified before. Mammography and ultrasound confirmed a left inferior breast mass, measuring 2.5 cm on ultrasound (Figures 1 and 2). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy confirmed poorly differentiated malignant neoplasm, estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor weakly positive, HER-2/neu negative.

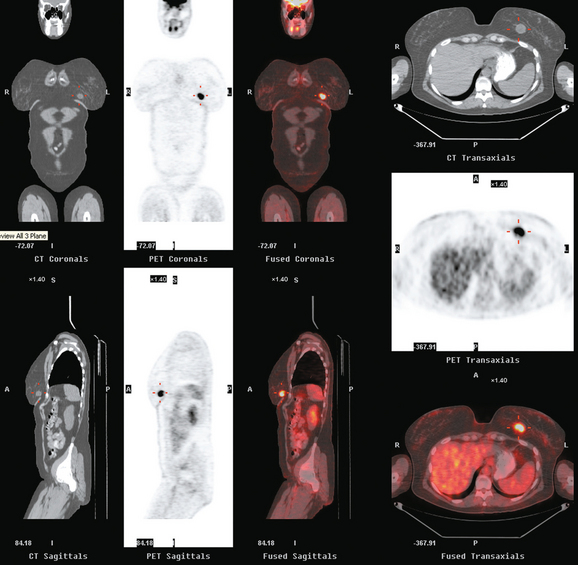

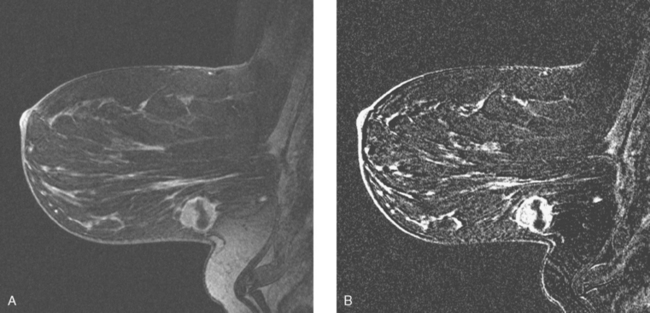

Breast MRI was requested because of the patient’s age, premenopausal status, and moderate breast density (Figures 3, 4, and 5). In addition to the index cancer, a separate concerning focus of clumped enhancement was noted in the lateral breast. This was subsequently targeted for biopsy with MRI guidance, obtaining fibrocystic changes (Figure 6). Two liver lesions were also questioned on breast MRI (Figure 7). Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and enhanced body CT scans were obtained to further evaluate the liver. No liver abnormality was confirmed on either modality. The liver findings questioned on breast MRI appeared to be relatively prominent vessels. On PET, an unexpected focus of hypermetabolism was noted in the pelvis, localizing to the uterus and corresponding with a uterine fibroid (Figures 8 and 9). The known left breast cancer was intensely hypermetabolic, but no PET evidence of nodal or metastatic disease was seen (Figures 10 and 11).

FIGURE 3 Axial enhanced breast MRI maximal intensity projection view of both breasts shows the posterior, intensely enhancing left dominant mass at 6 o’clock. A separate region of concerning clumped enhancement was noted anterolateral to the index tumor (arrow), better seen in Figure 4.

FIGURE 5 Sagittal, delayed, enhanced, fat-saturated, T1-weighted gradient echo views of the left breast. A, Unsubtracted. B, Subtracted. Rim enhancement is seen of the inferior breast cancer as well as spiculation of posterior margins. The subtraction is suboptimal, presumably because of a slight change in the patient’s position between the precontrast and postcontrast imaging (about 5 minutes elapsed, during which an axial dynamic series was obtained). The imperfect subtraction can be recognized by the prominence of the inferior skin surface and alternating light and dark bands at fibroglandular interfaces. Contrast this appearance with Figure 4 from the axial dynamic series, which shows near-perfect registration and no corresponding subtraction artifacts.

Palpation-guided lumpectomy and sentinel lymph node sampling were performed. The specimen contained a 2.5-cm medullary carcinoma, grade 9/9, with negative margins. One sentinel and two additional axillary lymph nodes were negative for malignancy. The final stage was stage II, T2N0M0. Additional therapy was given in the form of four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) plus cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) chemotherapy, radiation, and tamoxifen.

TEACHING POINTS

This case illustrates many of the typical features of medullary carcinomas. Medullary carcinomas are a variant of ductal carcinoma and account for less than 10% of breast cancers overall. They are more common in younger women (11% of all breast cancers in women younger than 35 years) and are rare in elderly women. They typically present as a well circumscribed mass and may mimic a fibroadenoma, both clinically and by imaging. These features have given rise to the term circumscribed carcinoma. Mammographically, this medullary carcinoma displays the typical innocuous appearance. Even by ultrasound, typical features of malignancy are not seen. This lesion did not adhere to Stavros’ probably benign criteria and was considered indeterminate sonographically, leading to biopsy. As in this case, the diagnosis may not be firmly made on core biopsy.

Depending on the breast MRI coil design and coverage and the patient’s anatomy, a variable portion of the liver will be visualized on breast MRI. This portion may be partially obscured by phase artifact from the heart, which generally is directed right to left, rather than anterior to posterior, to minimize obscuring the breasts. The breast imager needs to carefully scrutinize the liver for lesions that could possibly represent metastases. In this case, the questioned liver lesions were seen only on enhanced series and were not confirmed on corresponding short tau inversion recovery (STIR) images. They likely represented hepatic veins, which appeared larger and rounder in the liver periphery than expected.

Finally, this case illustrates a source of benign pelvic activity seen occasionally on PET, which should not be mistaken for pathology. Fibroids can unpredictably show hypermetabolism on PET. PET/CT generally permits confident localization of such activity to the myometrium, allowing differentiation from other sources of uterine activity, such as the normal variant endometrial activity that can be seen in premenopausal women during menstrual and ovulatory phases of the cycle (weeks 1 and 3).

CASE 7 Invasive lobular carcinoma

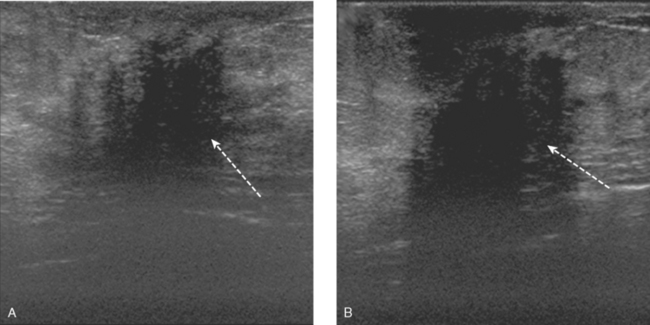

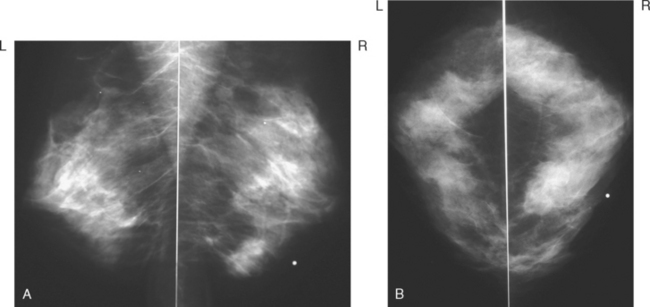

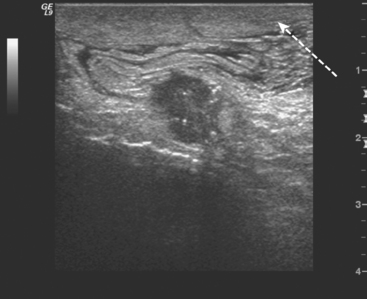

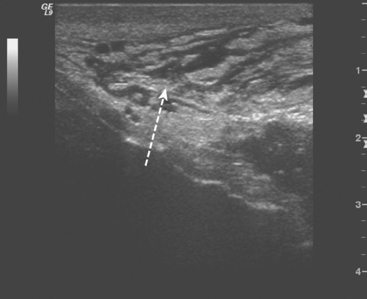

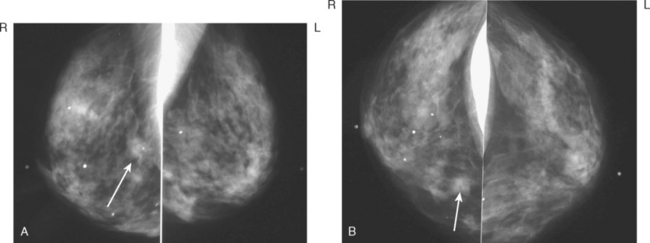

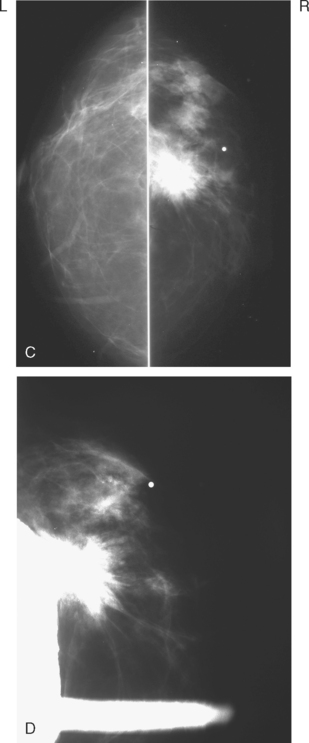

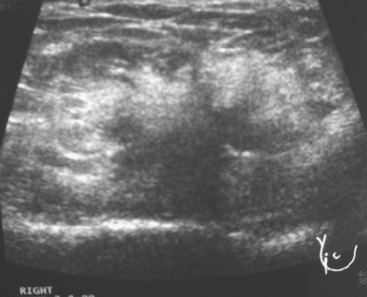

A 68-year-old woman presented with left breast nipple retraction and palpable fullness. Mammographic views demonstrated increased density in the medial subareolar left breast and mildly prominent left axillary nodes (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Ultrasound of the left breast demonstrated scattered areas of acoustic shadowing and small solid masses (Figures 5 and 6). MRI revealed diffuse abnormal enhancement of the central left breast as well as enlarged left axillary nodes (Figures 7 and 8). Subsequent ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of multiple areas of the left breast confirmed multicentric invasive lobular carcinoma. The patient was treated surgically with mastectomy and lymph node dissection.

TEACHING POINTS

Invasive lobular carcinoma represents about 10% of all invasive breast cancers. However, because they are frequently diffusely infiltrating and may not present as a discrete mass, they can be difficult to detect. In addition, invasive lobular carcinoma has a higher rate of multicentricity and bilaterality than ductal carcinoma. This example of invasive lobular carcinoma illustrates the limitations of mammography and ultrasound to accurately delineate the extent of breast involvement in some cases.

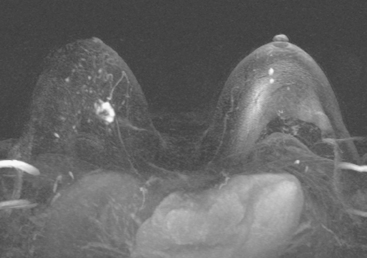

CASE 8 ILC presenting with orbital metastasis, bilateral shrinking breasts

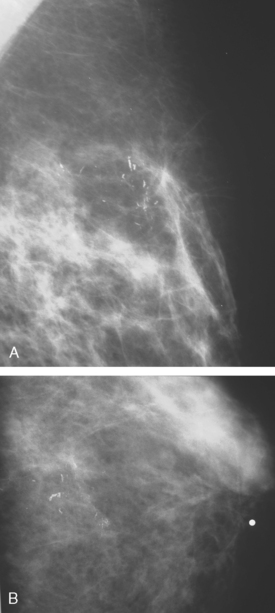

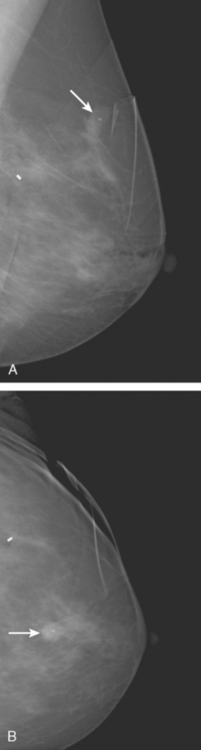

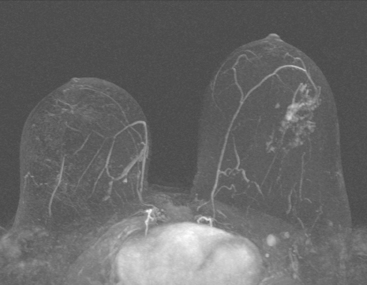

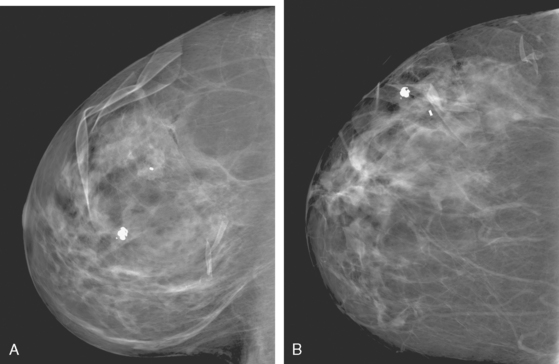

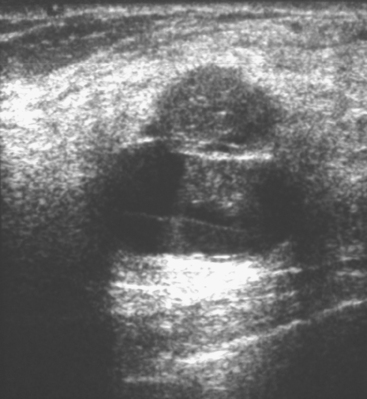

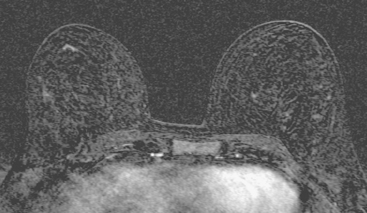

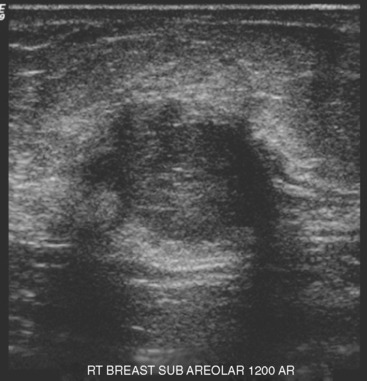

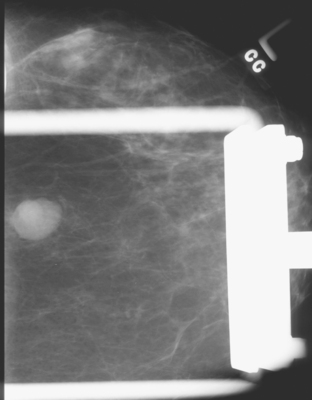

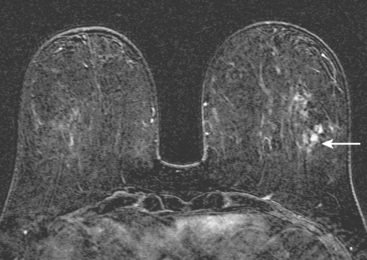

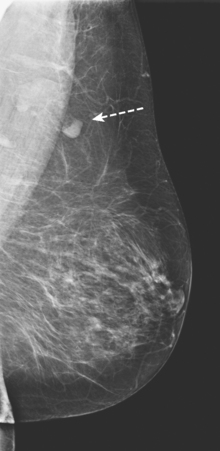

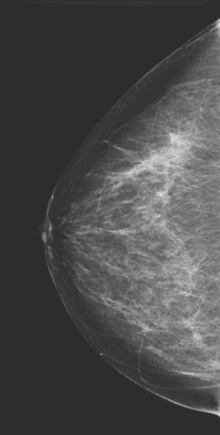

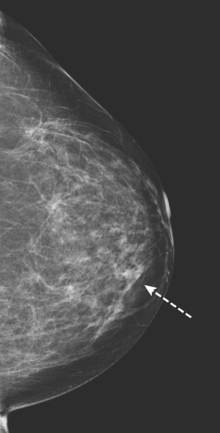

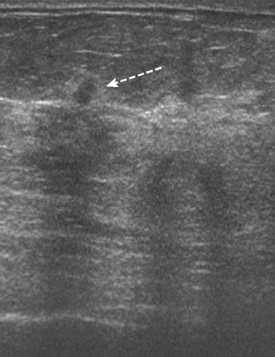

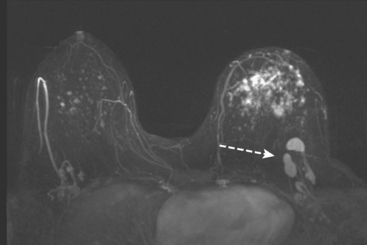

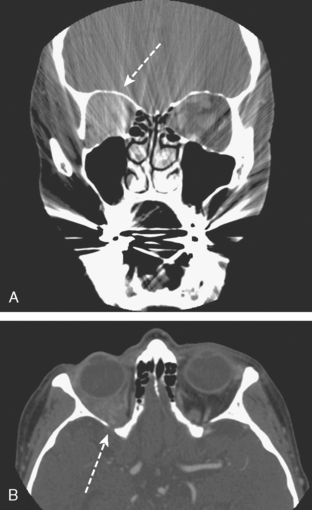

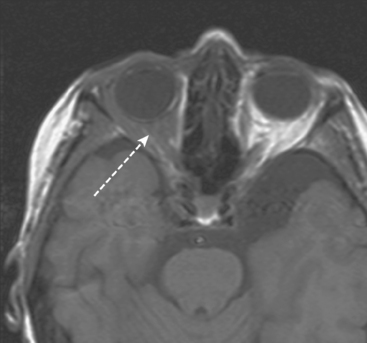

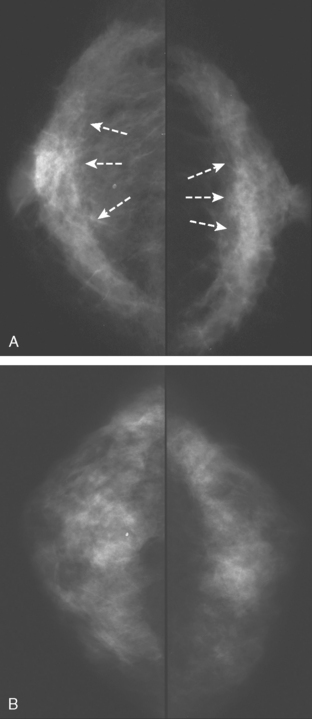

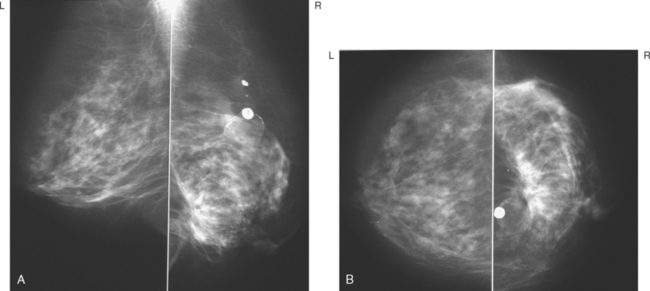

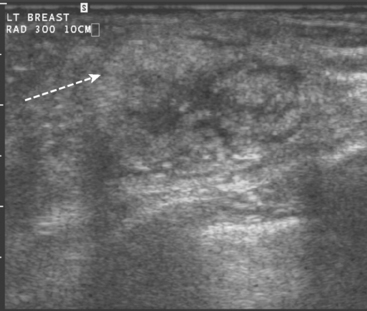

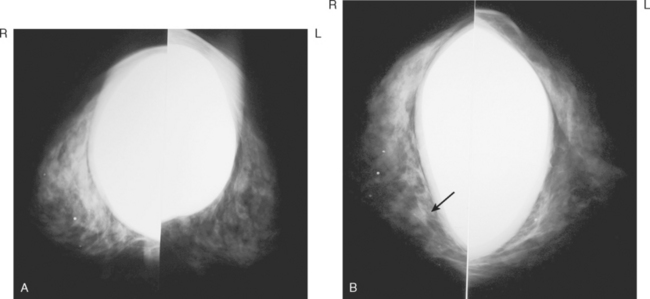

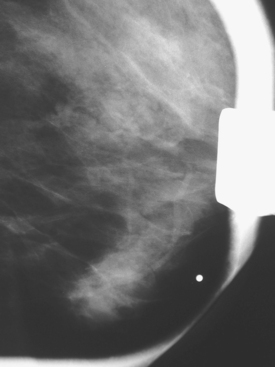

A 72-year-old woman presented to her physician for evaluation of right eye pain. Prior routine screening mammograms had been reported as normal. Ophthalmic evaluation and orbital imaging showed a right intraconal mass, accounting for the patient’s symptoms (Figures 1 and 2). The mass was biopsied and revealed adenocarcinoma, suspicious for a breast cancer metastasis. Review of the patient’s mammograms was performed (Figure 3), as well as ultrasound and MRI. Bilateral, nonmass areas of enhancement on MRI (Figure 4) corresponded to dense shadowing areas in the subareolar regions on ultrasound (Figure 5). Subsequent core needle biopsies confirmed bilateral invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC).

TEACHING POINTS

This case illustrates the insidious nature of invasive lobular carcinoma. Because ILC often invades the breast as sheets of single cells rather than forming a distinct mass, it may be difficult to detect and tends to be larger at diagnosis when compared with invasive ductal carcinomas. Fortunately, ILC accounts for only 6% to 9% of breast cancers, and their stage at diagnosis is similar to that of invasive ductal carcinomas. Mammography commonly underestimates the size of ILCs. As sheets of tumor cells infiltrate the breast, they may make the breast less compressible and appear smaller on mammography than the unaffected breast. This has been termed the “shrinking breast” sign on mammography. Diffuse involvement of the breast by ILC is usually obvious clinically, with the patient describing a hardening, lump, or thickening of the breast. This example is unusual in that the patient had involvement of both breasts simultaneously. Because of the gradual and symmetrical nature of the clinical changes, the patient did not seek medical attention. It was only when she began experiencing right eye pain that she consulted her physician. Metastatic disease accounts for about 2.5% to 13% of all orbital tumors. Breast carcinoma is the most common primary source of orbital metastasis. This case highlights the importance of an awareness of breast cancer as a source for orbital metastasis, not only in patients with a prior history of breast cancer, but also in patients with no prior history. This case is also unusual in that most patients with orbital metastasis have concomitant nonorbital metastasis. The patient in this example had no known metastasis elsewhere in the body at the time of presentation.

Harvey JA. Unusual breast cancers: useful clues to expanding the differential diagnosis [review]. Radiology. 2007;242(3):683-694.

Saitoh A, Amemiya T, Tsuda N. Metastasis of breast carcinoma to eyelid and orbit of a postmenopausal woman: good response to tamoxifen therapy. Ophthalmologica. 1997;211:362-366.

Talwar V, Vaid AK, Doval DC, et al. Isolated intraorbital metastasis in breast carcinoma: case report. JAPI. 2007:55.

Toller KK, Gigantelli JW, Spalding MJ. Bilateral orbital metastases from breast carcinoma: a case of false pseudotumor. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1897-1901.

CASE 9 ILC presenting as a mass; postoperative changes on CT and PET

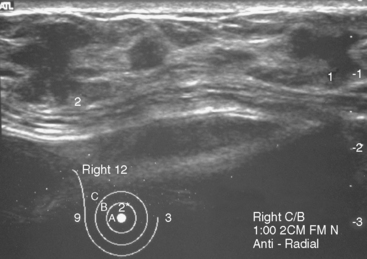

A 51-year-old asymptomatic woman underwent routine mammographic screening, which suggested a possible 1-cm mass overlying the pectoral muscle on the left MLO view. Additional mammographic spot compression and ultrasound confirmed a suspicious abnormality (Figure 1). Biopsy with ultrasound guidance confirmed infiltrating lobular carcinoma (ILC).

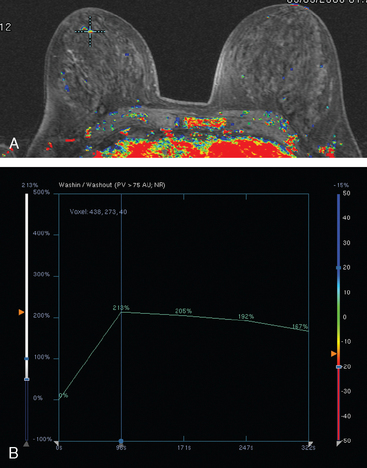

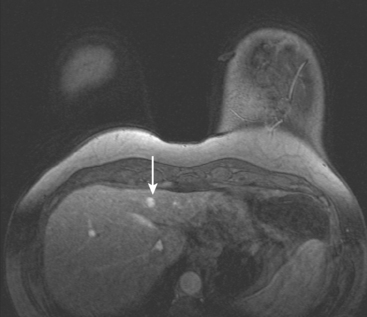

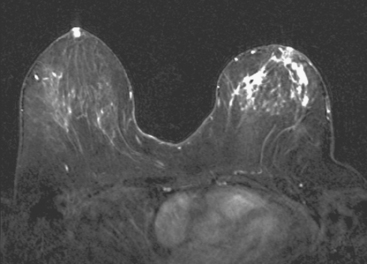

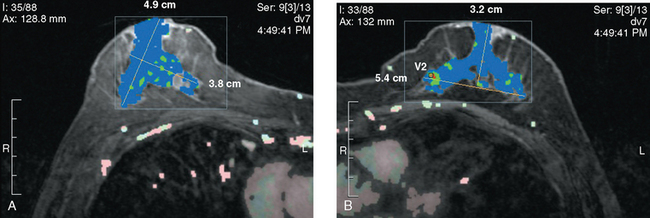

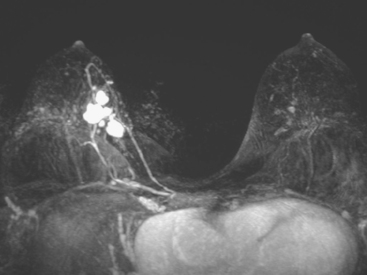

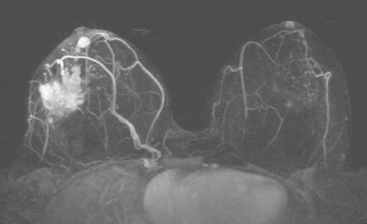

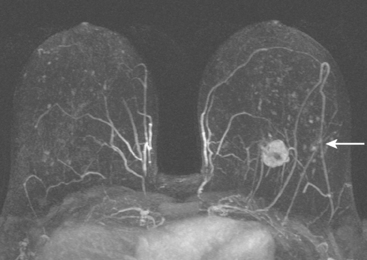

Because of the ILC histology, breast MRI was obtained preoperatively to screen the opposite breast and evaluate the extent of the known ILC (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The known left lateral ILC manifested as an 11-mm irregularly marginated mass with plateauing enhancement. Anteromedial to the index tumor was an additional enhancing 5-mm nodular focus, also with plateauing enhancement.

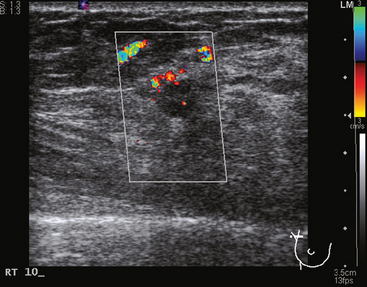

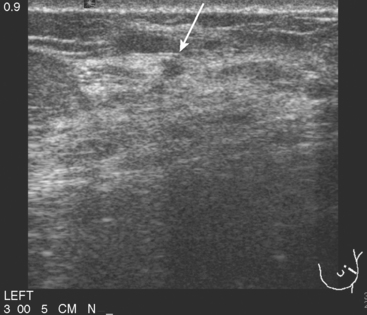

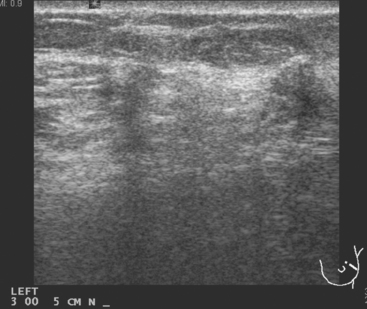

At the time of presentation for ultrasound-guided needle localization, a second-look ultrasound showed a 3-mm indeterminate sonographic finding near the index lesion (Figures 5 and 6). This seemed to correlate with MRI and was needle-localized at the same time.

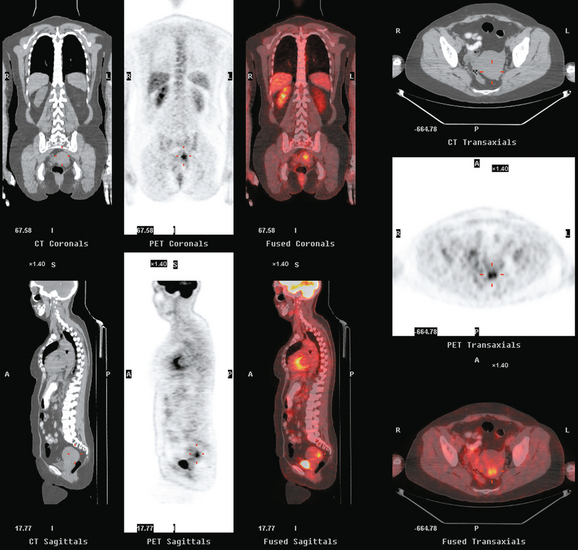

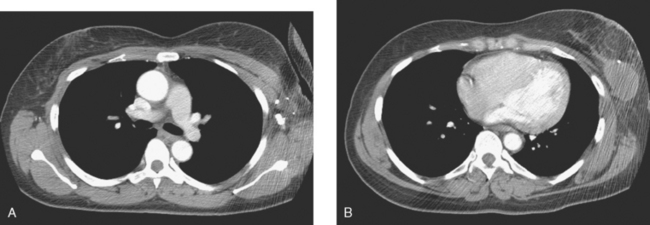

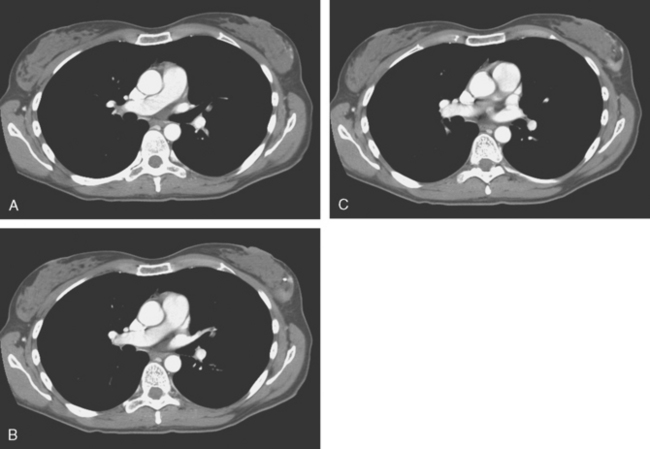

Because of the nodal involvement, systemic staging studies were obtained, including bone scan and PET/CT. PET/CT showed changes compatible with a 1-week-old axillary dissection, as well as 3-week-old postlumpectomy changes (Figures 7, 8, and 9).

TEACHING POINTS

How do we account for the apparent size discrepancy between the tumor seen on mammography, sonography, and MRI, which measured 1.1 cm, and the tumor at final pathology, which measured 2.7 cm? In this case, the gross tumor mass corresponded well to the size predicted by imaging evaluations.

If we measure the tumor size (from the sagittal MRI, Figure 4), and include both the 11-mm known ILC and the 5-mm “satellite” lesion anterior to it, and encompass the tissue between, we obtain a dimension of 2.7 cm. We know ILC can be variable in enhancement intensity on MRI. Presumably, some of this ILC did not enhance much. Conferring with the pathologist helps to suggest a resolution to questions of this nature. In this case, the gross specimen was sectioned, divided by the number of sections taken, with the tumor size estimate resulting from the number of sections taken multiplied by the number with tumor. The tumor had areas of infiltrating lines of tumor cells into fat and surrounding normal breast ducts. We can hypothesize with this information that the two tumor nodules seen on imaging represent foci within continuous tumor from the pathologic standpoint.

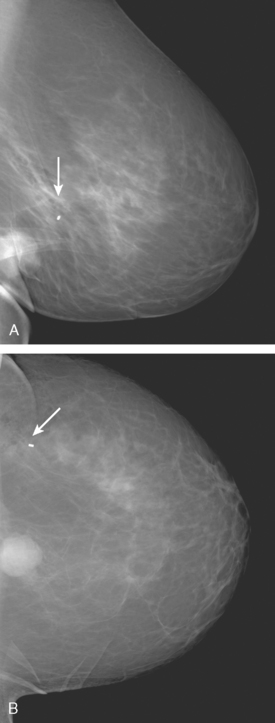

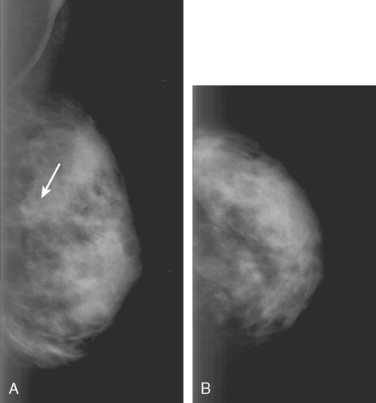

CASE 10 ILC presenting as architectural distortion

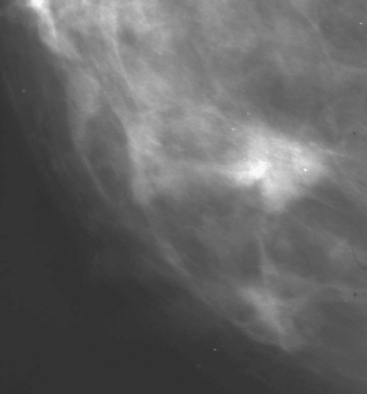

A 78-year-old female with two prior benign right breast biopsies had increased architectural distortion noted at the right 6-o’clock level on screening mammography (Figure 1). This was near a 20-year-old excisional biopsy site. Increased density and architectural distortion was confirmed on spot compression (Figure 2), and sonography demonstrated a corresponding shadowing mass (Figure 3). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy confirmed infiltrating lobular carcinoma (ILC). Because of the ILC histology, preoperative breast MRI was performed and showed the opposite breast to be clear. The known ILC manifested as a spiculated region of progressive intense enhancement, with no other sites of disease (Figure 4).

TEACHING POINTS

In this case, the diagnosis of ILC was established by ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy, and MRI was obtained to assess the extent of the known ILC and to evaluate the opposite breast. ILC has a known propensity for bilaterality, up to 30%, and is a clear indication for breast MRI. The morphology of the ILC enhancement is abnormal, with irregular, spiculated margins, and correlates well with the mammographic and sonographic manifestations of this tumor. The enhancement pattern was progressive, which is more typical of ILC than IDC. As many authors have previously noted, morphology should trump kinetic information. Kinetic data are most helpful when it is abnormal and may increase one’s suspicion level regarding morphologically bland-appearing findings. Conversely, kinetic data that suggest benignity (progressive enhancement) should not reassure one about a morphologically concerning finding.

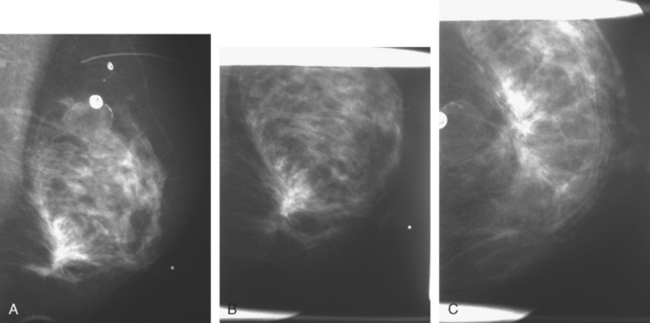

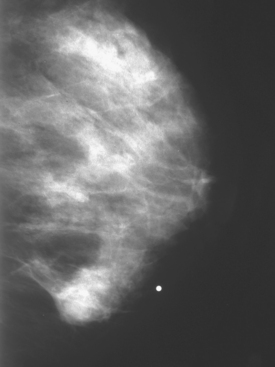

CASE 11 ILC presenting as a palpable, predominantly hyperechoic ultrasound mass

A 55-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of firmness palpated in the right medial breast. Mammography showed heterogeneous increased breast parenchymal density, but suggested a probable mass at the level in question (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Ultrasound confirmed a discrete mass with an unusual sonographic appearance, being predominantly hyperechoic (Figure 4). The diagnosis of invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) was made by palpation-guided core biopsy. Because of the breast parenchymal density and histology of ILC, the patient was further evaluated for breast conservation therapy with MRI. Breast MRI showed the known right ILC to have malignant features, including rim enhancement and washout (Figure 5). No indication of additional malignancy was seen in the right breast, with only scattered, fibrocystic-type tiny foci of enhancement noted. The left breast showed two small, sub-centimeter enhancing masses adjacent to each other in the anterior medial retroareolar breast (Figure 6). Ultrasound showed possible correlates of round hypoechoic masses (complex cysts versus solid masses by ultrasound) (Figure 7), which were subsequently needle-localized for excision at the time of contralateral mastectomy, and proven benign. The left breast pathology showed fibrocystic change and sclerosing adenosis. The right mastectomy specimen showed a 1.3-cm ILC, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive, HER2/neu negative, with one negative sentinel node. Because of a close surgical margin, the patient was also treated with chest wall radiation with a boost to the surgical bed.

FIGURE 3 Spot compression in the MLO projection shows that the mass fails to compress or change shape.

TEACHING POINTS

ILC represents up to 15% of all breast cancers and frequently is more difficult to diagnose than infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Clinically, it can be occult. Conversely, when it does present as a palpable mass, the clinical findings can at times be more impressive than the imaging findings, which can be relatively subtle. For this reason, clinically impressive palpable masses should be considered for palpation-guided biopsy, if the imaging evaluation is negative. Classically, ILC on histology grows as lines of tumor cells, extending tendrils through the parenchyma in single-file manner. This growth pattern underlies the difficulty that can be encountered in diagnosing ILC on imaging. Because there may not be a concentrated mass of confluent tumor cells, 15% of ILC may manifest on mammography as architectural distortion alone (sometimes best seen on a CC projection), without a true mass at the center. On ultrasound, ILC producing architectural distortion may manifest as an area of ill-defined shadowing, where margins of a mass are difficult to define. On MRI, enhancement of an ILC growing in this manner may be subdued and segmental compared with ILC- and IDC-forming masses. This growth pattern may also contribute to the positron emission tomography tendency of ILC to be less hypermetabolic than IDC.

That said, at least 40% of ILCs do form a mass, and in this presentation, the imaging findings parallel those of IDC. This is such a case. The mass is suspected based on mammography, but poorly delineated from the dense parenchyma. The ultrasound appearance is interesting, being predominantly hyperechoic. It fails Stavros’ criteria for benignity by virtue of being heterogeneous, with hypoechogenicity centrally and peripherally. As Stavros noted, hyperechoic masses usually are benign, but they must be uniformly hyperechoic to be characterized as benign. This appearance is not specific, and a very similar-appearing echogenic IDC is presented as a companion case in this chapter (Case 12).

The MRI features are malignant, with rim enhancement and washout. The MRI performed axially provides an opportunity for simultaneous evaluation of the opposite breast. Given both the propensity of ILC to be bilateral (up to 28% of the time) and the conventional breast imaging limitations in delineating the full extent of ILC, MRI is advocated for routine preoperative local staging of a new diagnosis of ILC, while simultaneously screening the other high-risk breast. Of course, not every focus of enhancement that turns up on breast MRI is cancer, and the use of breast MRI in such imaging evaluations will require follow-through and further workup of additional findings of concern on MRI. In this case, two small, adjacent, subcentimeter, benign-appearing but indeterminate nodules were seen on the opposite side. Ultrasound found suggestive correlates, which could have been sampled preoperatively with ultrasound guidance, but which in this case were needle-localized at the time of the contralateral lumpectomy, and proved benign. The significance of small enhancing masses like these on MRI should not be underestimated. See Case 14 in Chapter 1 for similar-appearing findings that proved to be malignant.

CASE 12 Echogenic breast cancer

A 78-year-old woman presented with a palpable left breast mass. Mammography confirmed a round mass in the lateral left breast. Ultrasound demonstrated an ill-defined, mixed echogenicity lesion, corresponding to the palpable mass (Figures 1 and 2). Core needle biopsy was performed and confirmed a low-grade invasive ductal carcinoma. The patient was treated surgically with lumpectomy.

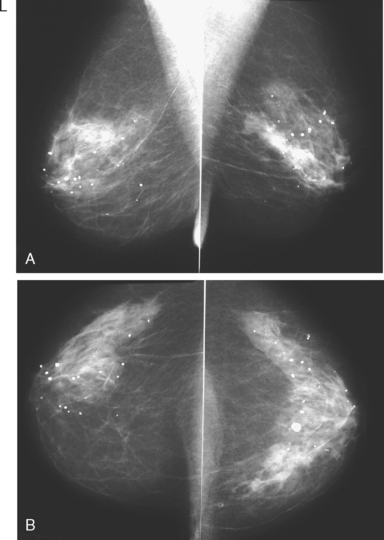

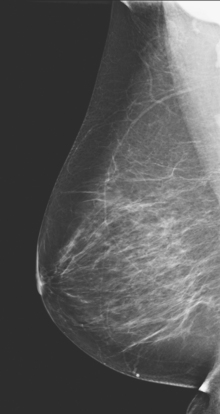

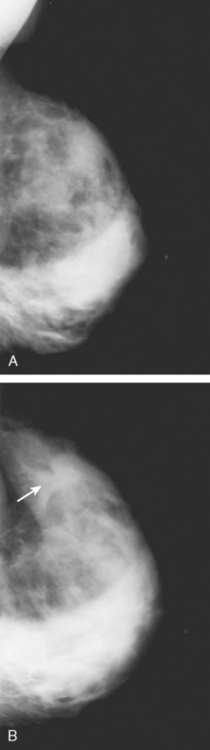

CASE 13 ILC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy

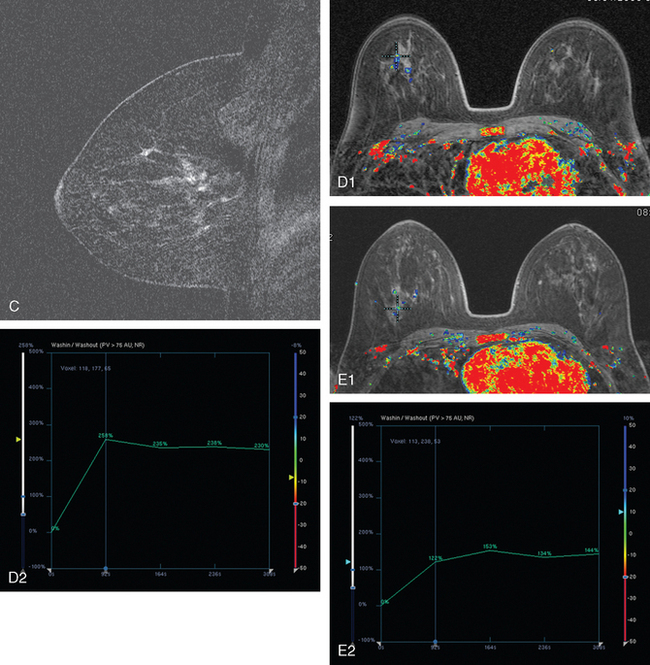

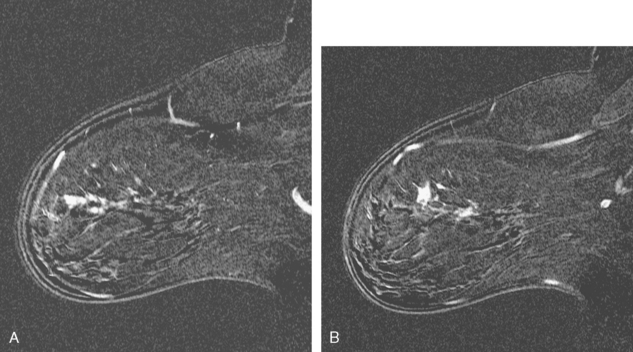

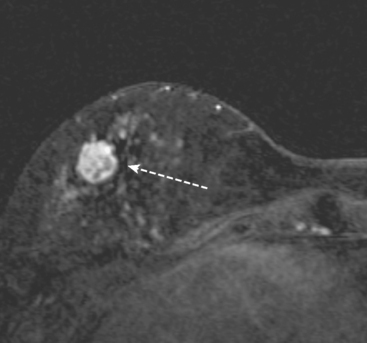

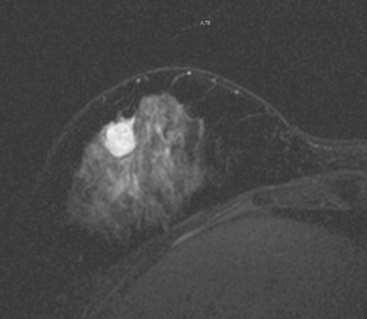

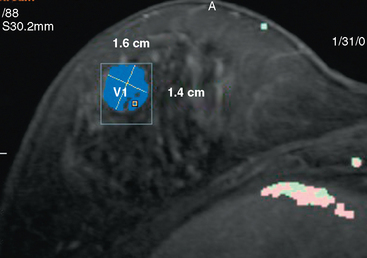

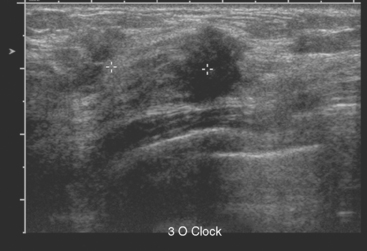

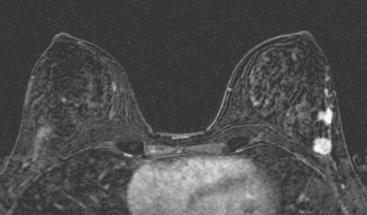

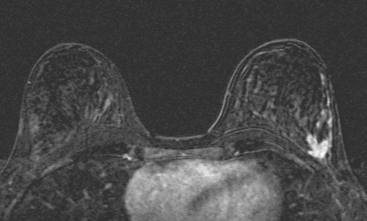

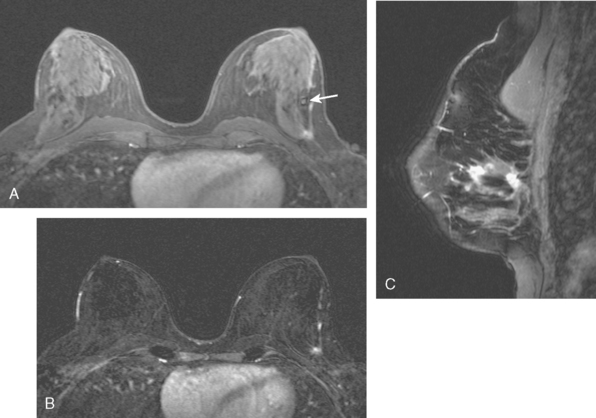

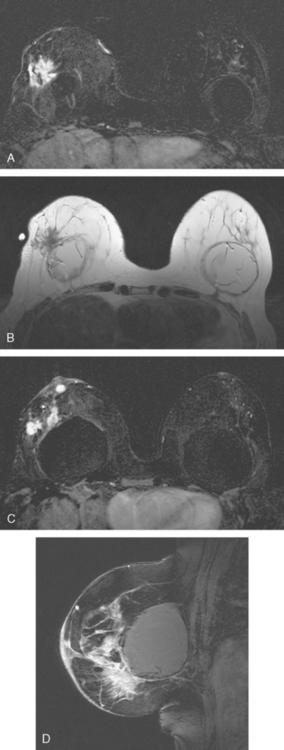

An asymptomatic 40-year-old woman with dense breasts underwent a routine screening mammogram (Figure 1). This raised a question of an abnormality on the left. Spot compression and ultrasound confirmed a 1.4-cm suspicious mass in the left lateral breast at 3 o’clock (Figures 2 and 3). Ultrasound-guided biopsy proved infiltrating lobular carcinoma (ILC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive, HER-2/neu negative.

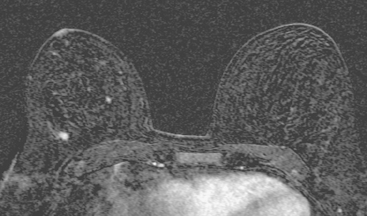

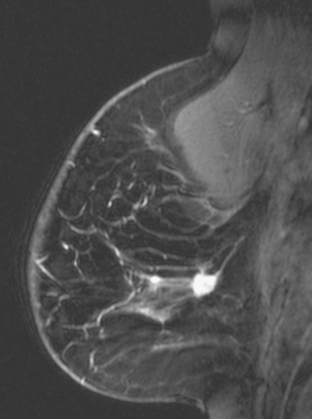

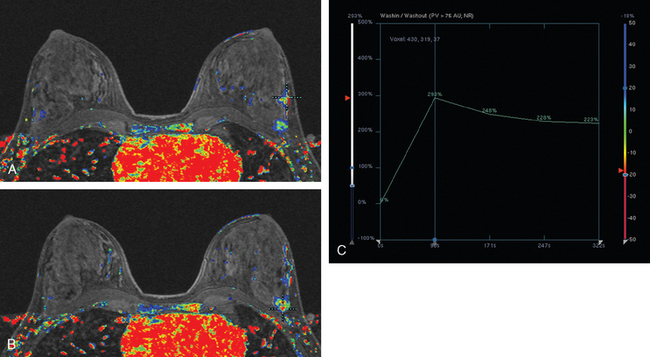

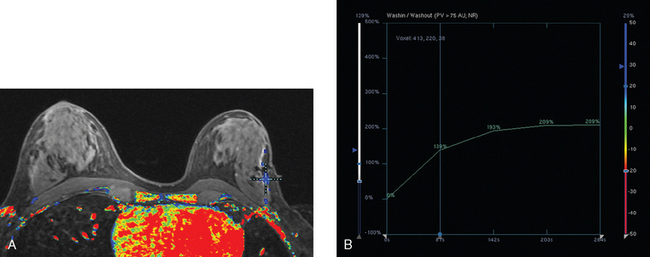

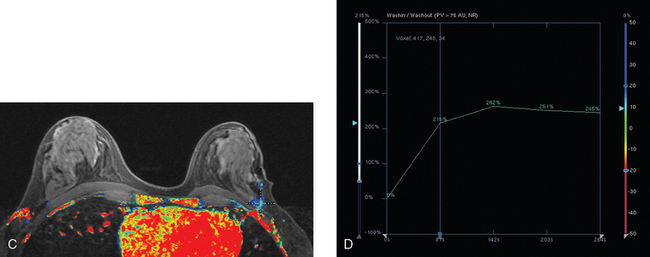

Because of the ILC histology and the breast density, breast MRI was performed to evaluate the full extent of disease in the involved breast and to screen the contralateral side (Figures 4, 5, and 6). Breast MRI showed the known index tumor in the posterior lateral left breast as an irregularly marginated, intensely rim-enhancing mass, with washout. Anterior to the known ILC was an additional 1-cm enhancing mass, as well as linear and clumped enhancement in a segmental distribution, extending anteriorly toward the nipple over an expanse of 6 cm.

The breast MRI results strongly suggested extensive, multifocal disease throughout the left lateral breast, indicating the patient was likely unsuitable for breast conservation therapy. To confirm multifocal disease, a second-look ultrasound was performed to determine whether a correlate for the additional disease suggested by MRI could be found. A subtle corresponding nodular focus was found anterior to the index lesion, and biopsy was performed with ultrasound guidance, also confirming ILC (see Figure 3). A clip was placed to mark the site.

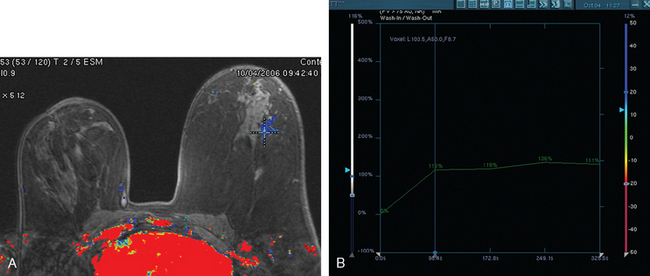

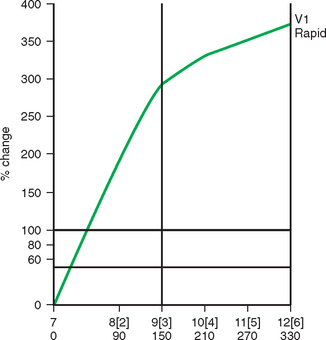

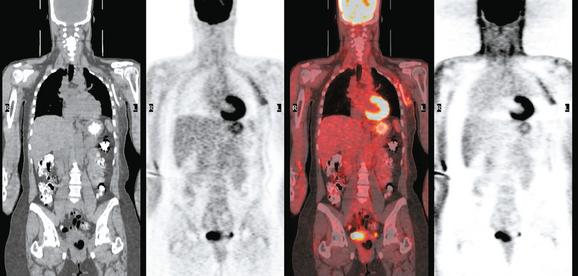

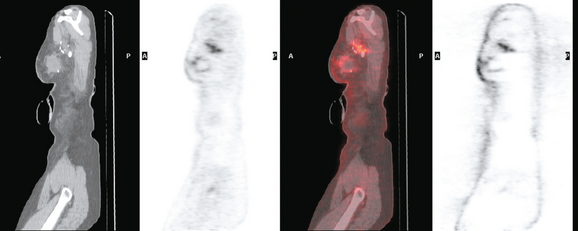

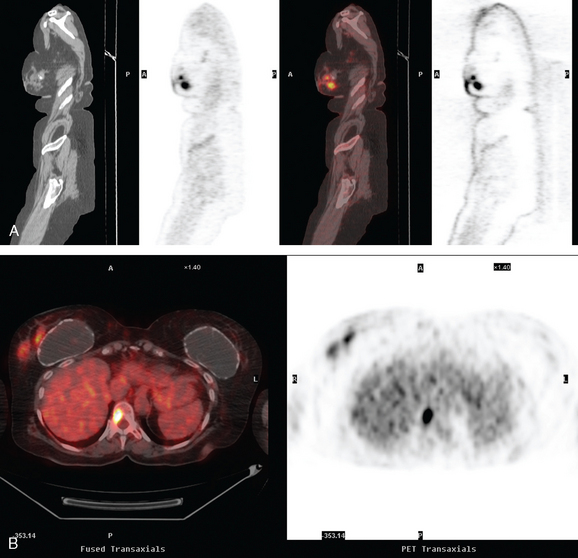

The patient was strongly desirous of breast conservation and elected to undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy. She was first staged with positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and contrast enhanced chest, abdomen, and pelvis CT, which showed only faint increased metabolic activity of the known left breast ILC (Figures 7 and 8). Four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), and four cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere) were administered, with repeat imaging assessment obtained at the midpoint and completion of chemotherapy (Figures 9, 10, 11, and 12). A partial response to chemotherapy was observed. The index lesion declined in size on ultrasound, although there was a persistent sonographically visible and vascular mass at final assessment. Serial breast MRI showed improvement as well, with progressive reduction in the size of the measurable masses, decline in enhancement intensity, and change in enhancement curve shape. There appeared to be considerable residual disease at final imaging assessment. Breast conservation was successfully achieved. Her lumpectomy specimen showed a 5-cm ILC, with no lymphovascular invasion and negative margins. Lymph node sampling showed five negative nodes. Additional treatment in the form of radiation and tamoxifen was begun subsequently.

TEACHING POINTS

This case provides many opportunities for discussion of some of the issues raised by an ILC diagnosis. This is a mammography screening success story, with mammography successfully raising alarm bells that this was a patient who needed additional imaging. Although it did not delineate the full extent of the disease, owing in part to the breast density, it succeeded in its screening role to identify the tip of a neoplastic iceberg. Prospective ultrasound, as is frequently the case, successfully found the index lesion and served to guide a biopsy to make the diagnosis, but did not prospectively demonstrate the full extent of involvement.

The role of breast MRI is well established as a valuable adjunct to better local staging of new ILC diagnoses. Not hindered by breast density, breast MRI can also (if performed bilaterally, usually in the axial plane) effectively screen the opposite breast for occult tumor, which occurs up to 10% of the time.

CASE 14 Stage IV ILC; presentation with liver metastases

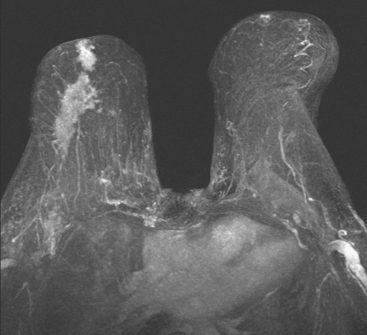

Breast MRI showed an extensive spiculated mass, occupying much of the upper outer quadrant (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5). A second focus of enhancing tumor at the retroareolar level was connected by an enhancing linear spicule. Multiple such linear tendrils could be seen extending from the dominant mass to the overlying skin, producing the clinically apparent dimpling. The left breast was unremarkable.

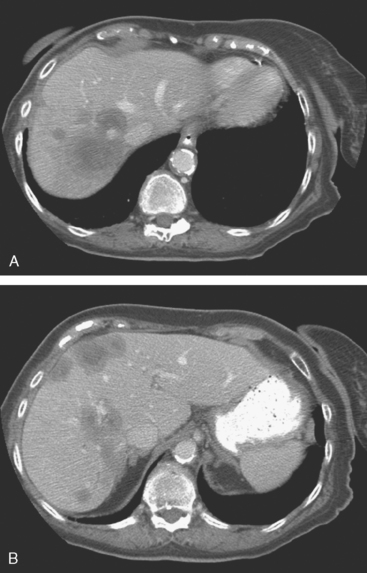

PET/CT showed hypermetabolism in at least four right axillary lymph nodes, as well as modest activity in the right breast mass. Multiple peripherally hypermetabolic, necrotic liver metastases were also identified, indicating that the patient’s true stage was actually stage IV (Figure 6). These correlated with hypovascular, peripherally enhancing, necrotic-appearing liver metastases on enhanced CT (Figure 7). No hepatomegaly was noted on physical examination, and the patient’s liver function tests, other than an elevated alkaline phosphatase, were normal. CT-guided biopsy was performed and confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma, consistent with breast carcinoma. Planned mastectomy was cancelled, and the patient was begun on letrozole (Femara).

TEACHING POINTS

This case serves to demonstrate many reported features and manifestations of ILC. Classically, ILC grows by infiltration of parenchyma by single-file rows of tumor cells. One of the known presentations of ILC is the “shrinking breast.” This can be difficult to recognize on mammography (see Case 8 in this chapter for a bilateral example). In this case, breast asymmetry could be appreciated clinically, and we can appreciate the counterpart findings on MRI. Skin dimpling could also be seen on clinical examination, and the MRI shows the imaging correlate. Multiple, fine, enhancing linear tendrils of presumed tumor could be seen extending to skin surfaces on this MRI.

Another described MRI characteristic of some cases of ILC is slower contrast accumulation and lower-level enhancement intensity, also seen in this case. Although the tumor mass is quite sizable, the enhancement intensity is less than that usually seen in comparably sized infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC). Most of the mass showed relatively slow wash-in, with eventual plateauing enhancement at 2 to 3 minutes of 200% above baseline. Only a tiny single focus of washout was found.

Depending on the configuration of the breast MRI coil, a portion of the liver is often included in the examination. This should not be relied on to consider the liver adequately imaged for clearance of significant disease, as this case amply illustrates. Even though this patient was demonstrated subsequently to have extensive liver metastases, these were not suspected or clearly identified even in retrospect on the breast MRI. Breast MRI coils are configured to provide maximal signal anteriorly and there is a rapid drop-off in signal posteriorly. The visualized portion of the liver is also often partially obscured by phase artifact from the heart (preferentially set right to left, rather than anterior to posterior, where it would obscure breast tissue). On occasion, a liver cyst will be seen with sufficient clarity on breast MRI to characterize it (bright on STIR or T2, and nonenhancing), but this is the exception (an example is illustrated in Chapter 9, Figure 5). More commonly, the breast imager who suspects or detects a liver lesion on breast MRI (which is not known from prior studies) will need to recommend a dedicated study to characterize it (either triple-phase CT or multiphasic enhanced MRI).

CASE 15 Ultrasound findings of inflammatory cancer

A 78-year-old woman presented to her physician with a swollen and erythematous right breast. Ultrasound of the right breast revealed a suspicious, 13-mm, solid breast mass with microcalcifications (Figure 1). In addition, findings of breast edema and skin thickening were seen, suggesting an inflammatory component (Figure 2). A skin punch biopsy was positive, confirming the diagnosis of inflammatory breast carcinoma. The patient was treated with mastectomy and axillary node dissection, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

TEACHING POINTS

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is a rare but very aggressive form of breast cancer, associated with an adverse prognosis. Cancer involvement of the lymphatics of the breast skin is the pathologic hallmark. The diagnosis is usually suspected on clinical exam with the rapid onset of breast edema, erythema, swelling, or the classic peau d’orange skin changes. It can be difficult to distinguish breast infection from inflammatory carcinoma, both clinically and on imaging. Skin punch biopsy can be helpful to confirm a suspected clinical diagnosis of IBC but is not required if the clinical presentation is characteristic and there is biopsy confirmation of cancer from a breast lesion. The constellation of imaging findings in this case, including a suspicious breast mass, breast edema, and skin thickening, are highly suggestive of inflammatory breast carcinoma.

CASE 16 Inflammatory breast cancer in a lactating patient

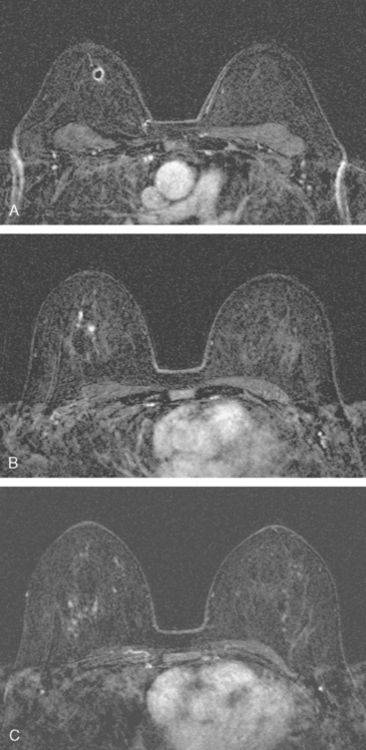

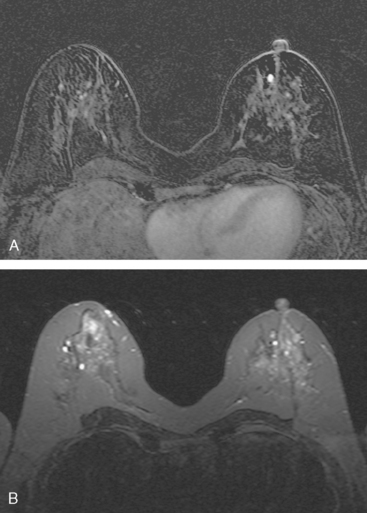

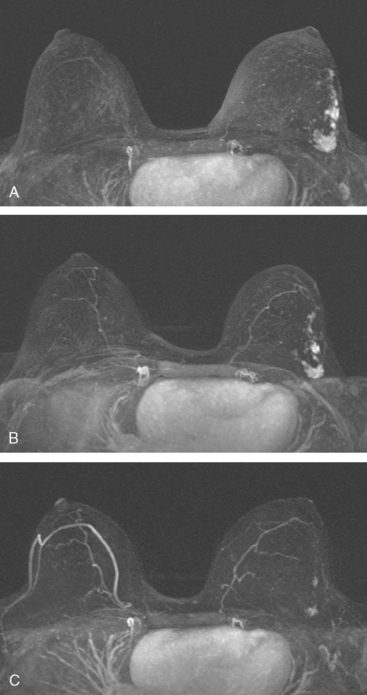

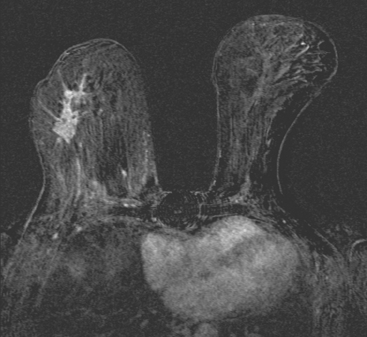

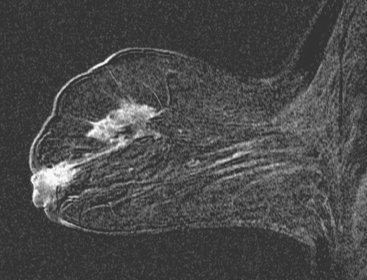

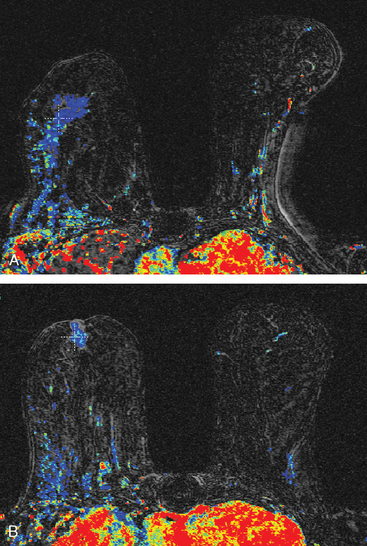

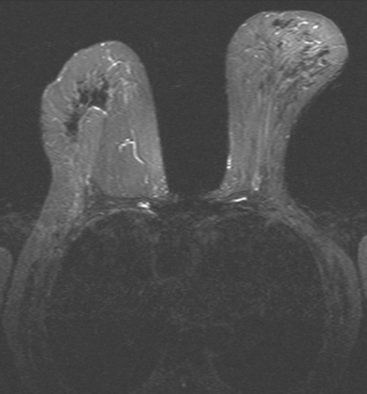

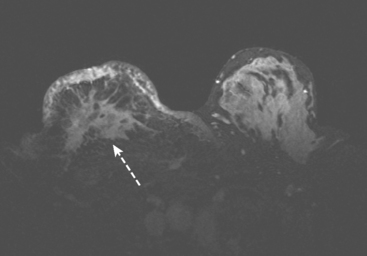

A 34-year-old lactating woman presented with symptoms of right breast pain, swelling, and erythema. Initially, the findings were thought to be due to breast infection. When the symptoms persisted, MRI was obtained (Figures 1, 2, and 3), a needle biopsy performed, and inflammatory breast cancer diagnosed.

CASE 17 Initial identification of breast cancer during breast MRI for implant integrity

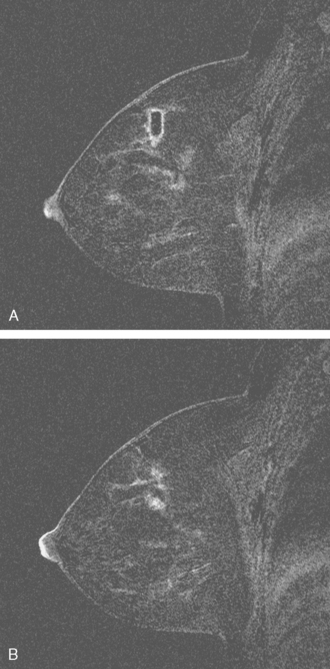

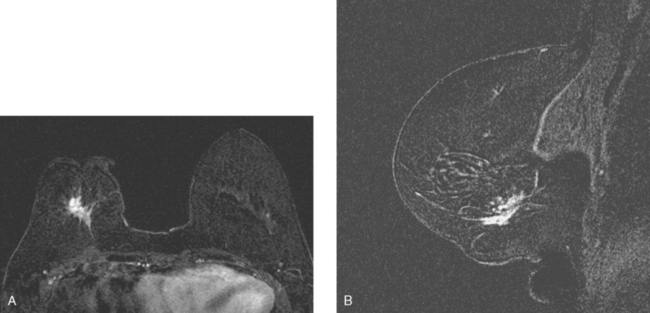

Because a palpable lump in an implant patient could be either a breast parenchymal mass or related to extracapsular silicone from implant failure, the study was conducted as a hybrid examination. Sequences were obtained both to evaluate the implants and to look for extracapsular silicone, with an enhanced, dynamic subtracted sequence obtained to evaluate the breast parenchyma.

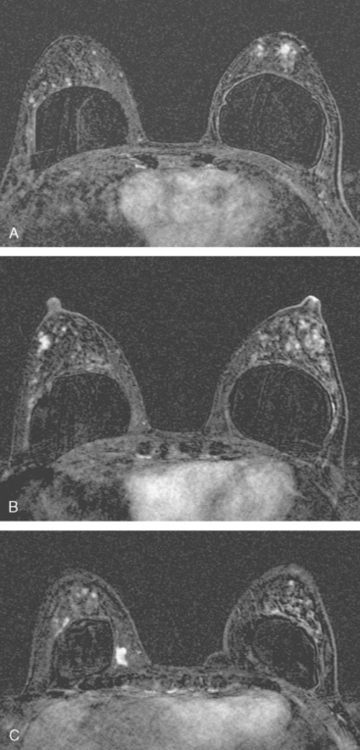

The implants proved to be double-lumen silicone and saline on the right and single lumen silicone on the left (not shown). The implants appeared intact, and no extracapsular silicone was seen. The breast parenchyma showed extensive fibrocystic enhancement, with three discrete sites of more intense mass enhancement (Figures 1 and 2). One was in the left breast at 12 o’clock, with washout. Two were in the right breast, one anteriorly at 8 o’clock and one in the lower inner quadrant at 5 o’clock along the implant margin. Both of these sites showed plateauing enhancement.

FIGURE 2 Sagittal, enhanced, subtracted, T1-weighted gradient echo images of both breasts, 5 minutes after contrast administration (A to C). A, Through the right lateral breast: The mass seen in Figure 1B at 8 o’clock is depicted. Margins are irregular. B, Through the right medial breast: The mass seen in Figure 1C is shown. It has an oblong shape and irregular margins. C, Through the left central breast: The early enhancing mass at 12 o’clock with washout now blends into adjacent enhancing breast parenchyma.

Ultrasound correlates were sought. A 1-cm mass with increased vascularity and angular, irregular margins was found on the right at 8 o’clock, correlating with MRI (Figure 3). No ultrasound correlates for either of the two other sites were found. The right 8-o’clock suspicious mass underwent biopsy with ultrasound guidance, confirming infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive.

TEACHING POINTS

If this patient had elected breast conservation therapy for her biopsy-proven right IDC, the question of what the second site of abnormal enhancement represented in the right lower inner quadrant at 5 o’clock would have had to have been addressed preoperatively. This would have been technically difficult. Its far posterior location in the medial breast and its position against the implant would have made MRI-guided biopsy difficult at best, assuming the lesion could even be reached from a medial approach, which limits how posterior a lesion can be accessed. An MRI-guided clip placement might have been possible, but a vacuum-assisted biopsy of a lesion against the implant margin runs the risk of rupturing the implant.

In this case, no correlate was found on MRI for the left palpable lump that prompted the MRI evaluation in the first place. Bilateral, suspicious, unsuspected abnormalities were identified, one of which proved to be a small breast cancer. This case points out the nonspecificity of appearance and enhancement characteristics of similar-appearing small MRI lesions. We have histologic diagnoses for two of these three lesions, with one a small IDC, another focal sclerosing adenosis and fibroadenomatous changes, and the other unknown.

CASE 18 Multifocal IDC in a patient with implants and dense breasts

An asymptomatic 71-year-old woman with bilateral subpectoral implants underwent screening mammography and subsequent breast ultrasound at an outside facility, which showed abnormalities suggesting multifocal right breast cancer (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Although the patient had noted no problems, physician examination after the imaging abnormalities were identified found a conglomerate of grape-like masses measuring 2 cm in the right medial retroareolar area. Palpation-guided core needle biopsy of a mass at 3 o’clock identified well-differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC). Because of the implants, breast density, and apparent multifocal nature of the patient’s disease, local staging was completed with breast MRI. This confirmed multifocal medial right breast cancer, but showed no evidence of disease elsewhere (Figure 5).

CASE 19 Large, locally advanced IDC in an implant patient

A 60-year-old woman with long-standing breast implants presented with a large palpable lump in the lower outer quadrant of the right breast, found on monthly breast self-examination. Mammography showed a spiculated mass at the level of the palpable lump on implant-displaced views (Figure 1). Ultrasound demonstrated a large (8 cm) vascular mass with angular and spiculated margins (Figure 2). Sonography of the axilla showed multiple enlarged, rounded, abnormal lymph nodes (Figure 3). Because of the implants, histologic sampling was accomplished with ultrasound guidance, and confirmed poorly differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinoma. Fine-needle aspiration of an axillary lymph node was performed with ultrasound guidance at the same time, and demonstrated malignant cells, consistent with metastatic disease. Breast MRI showed a large dominant tumor mass, with additional satellite lesions (Figures 4 and 5). No evidence of occult disease was seen in the contralateral breast. Because of the large size of the mass, thought to be T3N1, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was given. Staging workup, completed during neoadjuvant chemotherapy, included bone scan, chest, abdomen and pelvis CT scans, spine MRI, and positron emission tomography (PET) (Figure 6). These evaluations showed bone metastases. (See Case 1 in Chapter 8 for a discussion of the imaging manifestations of this patient’s bony metastatic disease.)

After completion of eight cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere), the patient was started on anastrozole (Arimidex) for her estrogen receptor–positive disease, as well as zoledronic acid (Zometa). She has been essentially asymptomatic on this therapy, with stable imaging studies for 2.5 years since the diagnosis of stage IV breast cancer metastatic to bone.