Undescended Testes and Testicular Tumors

Undescended Testes

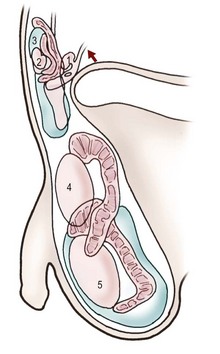

Normal testicular descent relies on a complex interplay of numerous factors. Any deviation from the normal process can result in a cryptorchid or undescended testis (UDT) (Fig. 51-1). UDT is a common abnormality that carries fertility and malignancy implications.

FIGURE 51-1 Testicular descent in males: 1, 90 mm crown–rump length (CRL) (12–24 weeks of gestational age); 2, 125 mm CRL (15–17 weeks); 3, 230 mm CRL (24–26 weeks); 4, 280 mm CRL (28-30 weeks); 5, at term. The convoluted structure is the epididymis. (Adapted from Hadziselimovic F. Embryology of testicular descent and maldescent. In: Hadziselimovic F, editor. Cryptorchidism: Management and Implications. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1983. p. 23.)

Embryology

Two important hormones in testicular descent are insulin-like factor 3 (INSL3) and testosterone, both secreted by the testis, while two important anatomic players are the gubernaculum testis and the cranial suspensory ligament (CSL). The gubernaculum is thought to help anchor the testis near the internal inguinal ring as the kidney migrates cephalad. Androgens prompt the involution of the CSL, allowing for eventual downward migration of the testicle.1 In humans, the frequency of UDT is increased in boys with diseases that affect androgen secretion or function.2,3 When anti-androgens are given to pregnant rats, the rate of UDT in male offspring is 50%.4,5 Estradiol downregulates INSL3 in experimental models, and maternal exposure to estrogens such as diethystilbesterol (DES) has also been associated with cryptorchidism.6,7

Under the influence of INSL3, the gubernaculum undergoes two phases: outgrowth and regression.8,9 Outgrowth refers to rapid swelling by the gubernaculum, thereby dilating the inguinal canal and creating a pathway for descent. Mice with homozygous mutant INSL3 have been found to have poorly developed gubernacula and intra-abdominal testes.10 Next, during regression, the gubernaculum undergoes cellular remodeling and becomes a fibrous structure.11 It is believed that intra-abdominal pressure then causes protrusion of the processus vaginalis through the internal inguinal ring, transmitting pressure to the gubernaculum and initiating testicular descent. However, the gubernaculum is not directly attached to the scrotum during inguinal passage, and does not act as a pulley. Transit through the inguinal canal is relatively rapid, starting around week 22 and typically completed after week 27.12,13

Other potential mediators of descent include MIF, by causing resorption of Müllerian structures and clearing anatomic roadblocks to descent, and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP).9 While research in rats has implicated CGRP in contraction of cremasteric muscle fibers and subsequent gubernacular and testicular descent,14,15 in humans the cremaster is distinct from the gubernaculum.12,16 In addition, growth factors such as epidermal growth factor act on the placenta to enhance gonadotropin release, which stimulates secretion of descendin, a growth factor for gubernacular development.8

Epididymal anomalies are found in up to 50% of men with UDT.17,18 Some investigators postulate that the gubernaculum facilitates epididymal descent, indirectly guiding the testis into the scrotum.19 Others believe that an abnormality of paracrine function is responsible for both epididymal anomalies and UDT, but that epididymal abnormalities are not causal.1

Classification

Variability in nomenclature regarding UDT has led to ambiguity in the literature and difficulty comparing treatment results. The clearest classification divides testes into palpable and nonpalpable.20 The distinction can be blurred, however, as when a previously palpable testis falls back into the abdomen through the open ring, or an intra-abdominal ‘peeping’ testis can be felt at the upper inguinal canal. A retractile testis is a normally descended testis that retracts into the inguinal canal as a result of cremasteric contraction; it is not an UDT. Though retractile testes do not require operative repair, in some series as many as one-third become ascending UDTs, suggesting either an initial difficult diagnosis or suboptimal attachment within the scrotum that changes position of the testis with growth of the child.21

A true UDT has halted somewhere along the normal path of descent from abdomen to distal to the inguinal ring. An ectopic UDT is one that has deviated from the path of normal descent and can be found in the inguinal region, perineum, femoral canal, penopubic area, or even contralateral hemiscrotum. Ascending or acquired UDT refers to a testis that was previously descended on examination, but at a later time can no longer be brought down into the scrotum. While an association between retractile testes and secondary testicular ascent has been identified, a link between rate of height growth and ascended testes suggests that the ability to reach the scrotum changes with a child’s growth.22,23 Acquired UDT may also be iatrogenic, as when a previously descended testis becomes trapped in scar tissue cephalad to the scrotum after inguinal surgery.

Incidence

UDT occurs in approximately 3% of term male infants and in up to 33–45% of premature and/or birth weight <2.5 kg male infants.24 The majority of testes descend within the first 6 to 12 months such that at 1 year, the incidence is down to 1%. Testicular descent after 1 year is unlikely.25 However, 2–3% of boys in the USA, and up to 5.3% in some European series, undergo orchiopexy for UDT.26,27 This discrepancy between higher orchiopexy rates and actual incidence of the disease is thought to lie partially in misdiagnosis between retractile testes, but also from acquired UDT. The overall rate of secondary testicular ascent has been reported between 2–45%.28,29

Series documenting the location of a UDT find that two-thirds to three-quarters of cases are palpable, usually within the inguinal canal or distal to the external ring.30,31 Anomalies associated with UDT include a patent processus vaginalis and epididymal abnormalities. Specific syndromes with higher rates of UDT include prune-belly syndrome, gastroschisis, bladder exstrophy, Prader–Willi, Kallman, Noonan, testicular dysgenesis and androgen insensitivity syndromes.22

Diagnosis

The patient should be examined in a warm room in both supine and frog-legged sitting position. The scrotum is observed for hypoplasia and examined for the presence of either testis. In cases of monorchia, the solitary testis may be compensatorily hypertrophied. The first maneuver to locate the testis is to walk the fingers from the iliac crest along the inguinal canal towards the scrotum, pushing subcutaneous structures toward the scrotum. The scrotum should not be palpated prior to this maneuver as it may activate the cremasteric reflex, thus retracting the testis. Lubricating gel or soap may help reduce friction. Gentle mid-abdominal pressure may help push the testis into the inguinal canal. A cross-legged sitting or squatting position may also help identify the testis. It can be particularly challenging to obtain an accurate exam on a ticklish or obese boy. Approximately 18% of nonpalpable testes are subsequently palpated when examined under anesthesia in the operating room.30,31

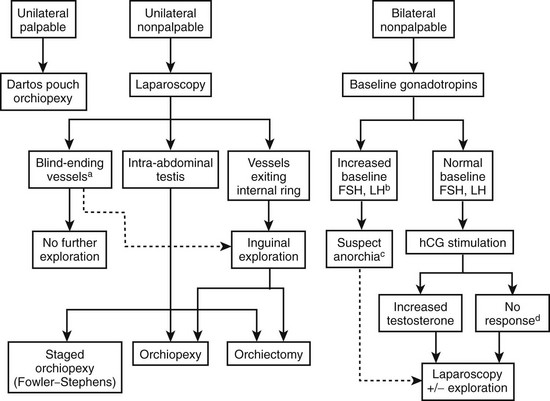

If neither testis is palpable, anorchia, androgen insensitivity syndrome, or a chromosomal abnormality must be differentiated from bilateral UDT. If the baseline follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level is elevated (three standard deviations above the mean) in a boy younger than 9 years, anorchia is likely and no further evaluation is recommended. If baseline luteinizing hormone (LH) and FSH levels are normal and human chorionic gonadotropic (hCG) stimulation results in an appropriate elevation of testosterone, functioning testicular tissue is likely to be present and the patient should undergo exploration. However, if the testosterone level does not increase appropriately, nonfunctional testicular tissue may still be present and exploration should still be performed. The hCG stimulation test does not distinguish between normal nonpalpable testes and functioning testicular remnants.32

Radiographic imaging is rarely helpful in locating a UDT and is not recommended routinely. Multiple studies have shown that the experienced surgeon/examiner has a higher sensitivity in locating the UDT than does ultrasonography (US), computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), especially because the sensitivity of imaging is poor in detection of soft tissue masses less than 1 cm.33 In unusual situations of bilateral nonpalpable testes, MRI with gadolinium may be useful for detecting abdominal testes because testicular tissue is particularly bright on MRI.34,35

While easy to perform with minimal risk, ultrasound has low accuracy with a sensitivity of 45% and specificity of 78%, and adds unnecessary cost.36,37 In one series, ultrasound incorrectly indicated UDT for 48% of patients when the testis was retractile.38 In summary, negative imaging is not diagnostic of testicular absence.

Fertility

A UDT and, to a lesser degree, its contralateral descended mate have been demonstrated to be histologically abnormal by investigators who performed bilateral testes biopsies at the time of orchiopexy.39,40 Clinically, patients with a history of UDT exhibit subnormal semen analyses.41 Early studies showed fertility to be related to the position of the UDT; men with abdominal or canalicular testes had lower fertility than those with inguinal testes (83.3% vs 90%).42,43 Despite these findings, the infertility rate of men with a history of unilateral UDT is equivalent to that of the normal population (10%).43,44,45 However, men with bilateral UDT have paternity rates of 50–65% even if corrected early, and thus are six times more likely to be infertile relative to their normal counterparts.46,47

Mechanisms of infertility in UDT appear to be associated with effects on Sertoli and Leydig cells, as well as Wolffian duct abnormalities (vasal and epididymal), which may further inhibit transport of already insufficient sperm.22 Elevated testicular temperature in a UDT results in immaturity of Sertoli cells in monkeys.22 A blunted normal testosterone surge at 60 to 90 days postnatally results in a lack of Leydig cell proliferation and delay in transformation of gonocytes to adult dark spermatogonia on histopathology.48 An experimental rat model has demonstrated preservation of germ cell number and spermatogenesis in rats undergoing early orchiopexy for UDT versus germ cell apoptosis in untreated rats.49 Furthermore, delayed orchiopexy at 3 years versus 9 months resulted in impaired testicular catch-up growth in boys.50

A clinical trial of neoadjuvant LH-releasing hormone (LHRH) in young boys undergoing orchiopexy appeared to improve the fertility index (spermatogonia/tubule) in treated versus untreated boys, though these results need confirmation.51 A similar prospective randomized trial on neoadjuvant gonadotropin-releasing hormone therapy prior to orchiopexy also found an improvement in the mean fertility index compared to the untreated group.52 Neoadjuvant therapy prior to 24 months achieved the best results.

Risk of Malignancy

UDT appears to be associated with a two- to eightfold increased risk of malignancy.25,53 The risk of malignancy arising from a UDT varies with location, e.g., 1% with inguinal and 5% with abdominal testes.54,55 Cancers arising in testes that remain in the abdomen are most frequently seminomas (74%).56,57 In contrast, malignancies arising after successful orchiopexy, regardless of original location, are most frequently nonseminomatous germ cell tumors (63%).58,59

Among men with testicular cancer, up to 10% have a history of UDT.60 There are two competing theories regarding this increased risk. First, the ‘position theory’ implicates the carcinogenic potential of the altered micro- and macro-environment of the UDT. If true, then the timing of correction could potentially lessen or negate the development of malignancy. A 2007 epidemiologic study examining 16,983 Swedish men who underwent correction of a UDT showed that those having orchiopexy before age 13 had a 2.23 relative risk of developing cancer.61 Those boys having surgery at 13 years or older had a relative risk of 5.40 (compared with normal men). An additional meta-analysis showed that orchiopexy after 10 years of age compared with before 10 was associated with six times the risk of malignancy.62 The association of orchiopexy with a decrease in cancer risk has not been demonstrated prospectively. Nevertheless, orchiopexy facilitates subsequent testicular examination and cancer detection.

The alternate ‘common cause’ or ‘testicular dysgenesis’ theory posits that the malignancy risk may be due to an underlying genetic or hormonal etiology that predisposes to both cryptorchidism and testicular cancer.63 In patients with a UDT, 15–20% of testicular tumors arise in the normally descended contralateral testis. In other words, the normally descended testis still carries an increased relative risk of 1.7.64 The incidence of carcinoma in situ (CIS) is 2–4% in men with cryptorchidism compared with less than 1% in non-affected men. In the postpubertal male, CIS progresses to invasive germ cell tumors in 50% of cases within 5 years.65 However, the natural history of CIS diagnosed in a young child at the time of orchiopexy is less clear. It has been recommended that these patients undergo repeated biopsies after puberty.66

Management and Treatment

Indications and Timing

Guidelines (AAP 1996 and EAU 2012) recommend that orchiopexy in otherwise healthy males be performed by 12–18 months of age, as the UDT is unlikely to descend after 12 months of age.67,68 Despite this recommendation, many children are referred after age 2 years. In one review of over 28,000 children with UDT in the Pediatric Health Information System database, only 18% underwent operation by 1 year of age, and 43% by 2 years of age. Black and Hispanic boys less commonly underwent orchiopexy by age 2 years, regardless of payer group and socioeconomic status.69 Repair may be undertaken even earlier if a symptomatic hernia is present. The risk of general anesthesia after 6 months is acceptably low in hospitals with dedicated pediatric anesthesiologists. In addition to the evidence that early scrotal placement may affect the risk of malignancy and infertility, treatment of a UDT also reduces the risk of torsion, facilitates testicular examination, improves the endocrine function of the testis, and creates a normal-appearing scrotum.

Hormonal Treatment

The value of hormonal therapy in the treatment of UDT is controversial. Buserelin, an LHRH agonist, is frequently used to treat UDT in Europe.70 The highest success rates have been observed in cases where the testis is at or distal to the external inguinal ring.71,72 Some authors recommend low-dose hCG therapy, regardless of the operative plan to restore a normal endocrine milieu and enhance germ cell maturation, particularly in bilateral UDT.73 Trials combining buserelin and hCG have yielded success rates in the range of 60%, but orchiopexy is still required in 40% of patients.74,75 Buserelin has not been approved for this use by the USA Food and Drug Administration, but as noted above, clinical trials of LHRH used in a neoadjuvant fashion in young boys undergoing orchiopexy suggest that it may improve fertility.51

Orchiopexy

The operative approach for UDT depends on whether the testis is palpable (Fig. 51-2). It is important to re-examine the patient under anesthesia because up to 18% of nonpalpable testes may become palpable on examination under anesthesia.76 Unilateral and bilateral palpable UDT are managed similarly. Routine biopsy of the testis at the time of surgery is not recommended, but may provide prognostic information regarding fertility.77

FIGURE 51-2 Management algorithm for undescended testis. FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin. (a) If blind-ending vessels are unequivocally identified, then there is no need for further exploration. (b) Baseline FSH and LH levels are elevated if values are 3 SD above the mean. (c) Increased suspicion of anorchia with elevated baseline FSH and LH levels; however, exploration is still warranted. (d) Testicular remnant tissue may be present despite a negative hCG stimulation test; therefore, exploration for testicular remnant tissue should still be performed.

For the unilateral palpable UDT that presents after puberty, orchiopexy is preferred. If orchiopexy is difficult and a normal contralateral testis is present, or if the UDT is abnormally soft and small, then an orchiectomy should be performed. Likewise, orchiectomy is the treatment of choice for the postpubertal, unilateral intra-abdominal UDT because of the increased cancer risk. Laparoscopic orchiectomy is ideal in this setting.78 In uncommon cases such as postpubertal males with significant anesthetic risks, or males older than 50, observation is an acceptable alternative to operation.56

Palpable Undescended Testes: Unilateral or Bilateral

The mainstay of therapy for the palpable UDT is orchiopexy with creation of a subdartos pouch.79,80 This may be performed through a standard two-incision (inguinal and scrotal) approach, or a single-incision high scrotal approach.81,82 With the standard inguinal approach, the success rate is as high as 95%.83 Similar success rates have been reported for the high scrotal approach.81,84 With both techniques, scrotal fixation is achieved by scarring of the everted tunica vaginalis to the surrounding tissues.85 Placement of sutures in the tunica albuginea for fixation is generally discouraged because it causes significant testicular inflammation, increases infertility risk, and may damage intratesticular vessels.86,87 Associated findings such as an open processus vaginalis or hernia should be repaired.

A standard inguinal approach to orchiopexy with a subdartos pouch is depicted in Figure 51-3. The operation is usually performed as an outpatient procedure under general anesthesia. The patient is supine. Intraoperative administration of an ilioinguinal nerve block with bupivacaine provides excellent postoperative analgesia. An incision is made along one of the Langer lines over the internal ring. The external oblique aponeurosis is incised in the direction of its fibers, avoiding injury to the ilioinguinal nerve. Once located, the testis and spermatic cord are freed from the canal and any cremasteric and ectopic gubernacular attachments. The tunica vaginalis is then dissected off the vas deferens and spermatic vessels. The proximal sac is twisted, doubly suture ligated, and amputated. Retroperitoneal dissection through the internal ring may provide additional cord length for the testis to reach the scrotum.

FIGURE 51-3 Standard inguinal orchiopexy approach. (A) Transverse skin incision. (B) External oblique aponeurosis is opened in the directions of its fibers, with care taken to avoid the ilioinguinal nerve. (C) The testis is delivered, and the patent processus vaginalis is opened distally near the testis. (D) The processus vaginalis (or indirect hernia sac) is separated from the cord structures and ligated at the internal ring. Adequate cord length is usually obtained by retroperitoneal dissection of the cord contents. If additional length is required, the inferior epigastric vessels may be ligated (Prentiss maneuver), permitting medialization of the cord. (E) A finger is passed inferiorly into the scrotum to aid in creation of the dartos pouch. (F–H) Dartos pouch creation and passage of a clamp through the scrotum into the inguinal canal. (I) Adventitial tissue of the testis is grasped with the clamp. (J) The testis is brought into the dartos pouch. (K) Dartos fascia and skin are closed. (From Ellis DG. Undescended testes. In: Ashcraft KW, editor. Pediatric Urology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1990. p. 423.)

The patient is seen in clinic after a few weeks for a wound check and again several months later for testicular examination, instruction on testicular self-examination, and repeat counseling on fertility and cancer risk. Final position and condition of the testis should be noted. Although rare, complications include atrophy and retraction. A single scrotal incision technique has also been applied to orchiopexy, with similar success rates and shorter operative times, but one group demonstrated an increased 3% risk of postoperative hernia with this approach.81,88

Nonpalpable Undescended Testes: Unilateral or Bilateral

For a unilateral UDT that is not palpable under anesthesia, initial management may be either through diagnostic laparoscopy or inguinal exploration. In the last decade, laparoscopy has become the preferred approach.89

If the surgeon decides to first perform inguinal exploration and no testis or remnant is identified, then diagnostic laparoscopy or laparotomy may still be needed to ensure the testis is not in an intra-abdominal location. In one retrospective review of 215 nonpalpable testes, only 34% were located distal to the internal ring, and an initial inguinal incision would have provided suboptimal exposure for the remaining 66%.90

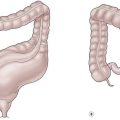

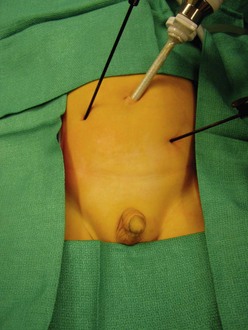

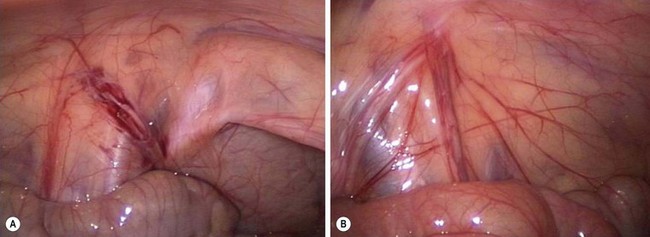

The surgeon may begin with diagnostic laparoscopy through an umbilical port (Fig. 51-4).91 If the vessels appear atretic or ‘blind ending’ as they exit the abdomen, some have recommended no further exploration, though this is controversial. If the testicular vessels are seen exiting the internal ring, a laparoscopic inguinal exploration is performed if the ring is open, or an open inguinal exploration if the ring is closed (Fig. 51-5).89 Orchiopexy is performed if a viable testis is found. If the vessels end blindly in the inguinal canal, the tip of the vessels can be sent for pathologic examination. Remnants of testicular tissue or hemosiderin and calcifications are indicative of probable perinatal torsion and testicular resorption.

FIGURE 51-4 After diagnostic laparoscopy through a 5 mm umbilical cannula, if ligation and division of the testicular vessels are required, two accessory 3 mm instruments are introduced into the abdominal cavity using the stab incision technique. The surgeon should stand on the side opposite the nonpalpable testis. (From Holcomb GW III. Laparoscopic orchiopexy. In: Holcomb GW III, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SS, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008. p. 144–8.)

FIGURE 51-5 (A) The vas deferens and testicular vessels in this patient end blindly in the retroperitoneum. The internal ring is closed. In this very unusual situation, inguinal exploration is not necessary. (B) In the more common scenario, the testicular vessels and vas deferens are seen to enter the inguinal canal. There is no evidence for a patent processus vaginalis. The vessels and vas deferens appear to be of relatively normal caliber. In this situation, inguinal exploration is necessary. (From Holcomb GW III. Laparoscopic orchiopexy. In: Holcomb GW III, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SS, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008. p. 144–8.)

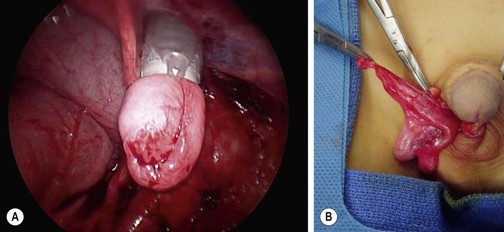

If diagnostic laparoscopy reveals a viable intra-abdominal testis, several options are available depending on its location. A recent review concluded that while there is not an optimal surgical technique for an intra-abdominal testis, preservation of the spermatic vessels is preferable.89 If the gonadal vessels are long enough to allow for tension-free mobilization of the testis into the scrotum, orchiopexy may be performed open or laparoscopically depending on surgeon preference (Fig. 51-6). This is often feasible when the testis lies caudal to the iliac vessels.78

FIGURE 51-6 (A) After intra-abdominal mobilization of the testis, the gubernaculum has been grasped with forceps inserted through a 10 mm cannula that has been introduced through the scrotal incision, over the pubic tubercle and into the abdomen. The testis is then withdrawn into the cannula. Often, it is not possible to place the testis entirely into the 10 mm port. (B) The testis is delivered over the pubic tubercle and into the right hemiscrotum. (From Holcomb GW III. Laparoscopic orchiopexy. In: Holcomb GW III, Georgeson KE, Rothenberg SS, editors. Atlas of Pediatric Laparoscopy and Thoracoscopy. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2008. p. 144–8.)

When the gonadal vessels are too short, there are various options. Open or laparoscopic exploration can be performed. The cord structures are mobilized cephalad towards their origin, freed from the posterior peritoneum, and the testicle brought into the scrotum. A neoinguinal ring may be created medial to the median umbilical ligament to shorten the path for scrotalization of the testis (Prentiss maneuver). Most series indicate a 95–100% success rate, defined as lack of atrophy and a normal scrotal position, with single-stage laparoscopic orchiopexy.89 A staged orchiopexy can also be performed in which the high abdominal testis with its cord structures is first mobilized as low as possible. Six to 12 months later, it is mobilized into the scrotum. The advantage of this approach lies in preservation of both primary and collateral blood supply. However, during the second stage, injury may occur to the vascular supply and/or vas deferens because of scarring to surrounding tissues.

Alternately, in the setting of a short spermatic cord, a first stage Fowler–Stephens orchiopexy can be performed, typically laparoscopically.92 The Fowler–Stephens orchiopexy involves clipping the spermatic vessels, which makes the testis dependent on the vasal and cremasteric vessels for viability.93,94 For this reason, the Fowler–Stephens approach is not a good option after prior inguinal exploration because this secondary vascular supply to the testis may have been compromised. A delay of six months is recommended before stage 2 to allow development of collateral circulation. During the second stage, the spermatic vessels are then divided between the clips, and the testis located into the scrotum. The success rate in modern single-center case series with follow-up longer than 3 years exceeds 90%.95–97 However, a higher failure rate was observed with a single-stage Fowler–Stephens orchiopexy, and caution is advised with this approach.

Other options for operative management of high intra-abdominal testes include microvascular orchiopexy (autotransplantation). This technique is infrequently used as it requires special instrumentation, microsurgical skill, and sometimes an unexpected need for a second microvascular surgeon. An 83–96% success rate in experienced hands has been reported.89

Boys with bilateral nonpalpable UDT usually have genetic, endocrinologic, or imaging evaluation indicating the presence or absence of testicular tissue (i.e., hormonal evaluation confirming testosterone production). If laparoscopy reveals only one viable testicle, the child is managed as in the situation with unilateral, nonpalpable UDT. However, if bilateral viable testes are found, management may depend on the ease of orchiopexy. If difficult, one side may be fixed first, with the contralateral side fixed six to 12 months later. This allows the practitioner to assess the outcome of the first side prior to operating on the contralateral testis.89

Secondary or Iatrogenic Undescended Testis

Secondary UDT is an uncommon complication of inguinal hernia repair, orchiopexy, or hydrocelectomy. Surgical technique differs from that of primary repair because scarring from the previous procedure makes cord dissection difficult with risk of vascular or vasal injury. Cartwright and associates described a technique for reoperative orchiopexy in which the entire cord and scar is mobilized en bloc along with a strip of external oblique aponeurosis.98 The testis/cord/aponeurosis complex is dissected together superior to the internal ring where the aponeurosis is then cut and dissection continued above the area of previous scar into the retroperitoneum to allow more extended mobilization. If more length is necessary, division of the inferior epigastric vessels allows the cord to be displaced medially.

Testicular Cancer

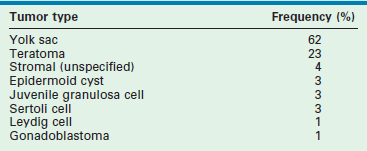

Testicular cancer is uncommon in children, accounting for 1% to 2% of all pediatric solid tumors. The peak incidence of pediatric testicular tumors occurs between ages 12 to 24 months, followed by a second small peak during puberty. Prepubertal boys have a much larger percentage of benign-behaving testicular lesions than postpubertal and adult males.99,100 Management of testicular tumors in prepubertal boys thus differs from postpubertal boys and adults as curative treatment may be partial or radical orchiectomy. These cancers generally respond well to chemotherapy, and retroperitoneal lymph node dissection (RPLND) is relatively rare.101 Germ cell tumors comprise 65–85% of pediatric testicular tumors. Tumor registries have reported that greater than 60% of tumors were yolk sac (YST) and approximately 20% were teratomas (Table 51-1).55,102 Males with gonadal dysgenesis, disorders of sexual development, and hypovirilization have an increased incidence of gonadal tumors.

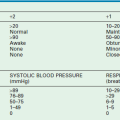

TABLE 51-1

Primary Testes Tumor Types in 395 Boys Under 12 Years of Age

Adapated from Ross JH, Rybicki L, Kay R. Clinical behavior and a contemporary management algorithm for prepubertal testis tumors: a summary of the Prepubertal Testis Tumor Registry. J Urol 2002;168(4 Pt 2):1675–8; discussion 1678–9.

Presentation and Diagnosis

A testicular tumor typically presents as a painless scrotal mass. A history of trauma is often given and may be the event that brings attention to the scrotal mass. Sometimes, a tumor arising in a UDT may cause torsion and present as acute abdominal pain. Malignancy typically is nontender, does not transilluminate, and is associated with a normal urinalysis. An associated hydrocele in 15–20% of patients may impede adequate testicular examination.101 Hormonally active tumors may cause precocious puberty. As part of the initial evaluation for a testicular mass, color Doppler testicular ultrasound and serum tumor markers (α-fetoprotein (AFP), β-hCG) should be obtained. Ultrasound is nearly 100% sensitive.101

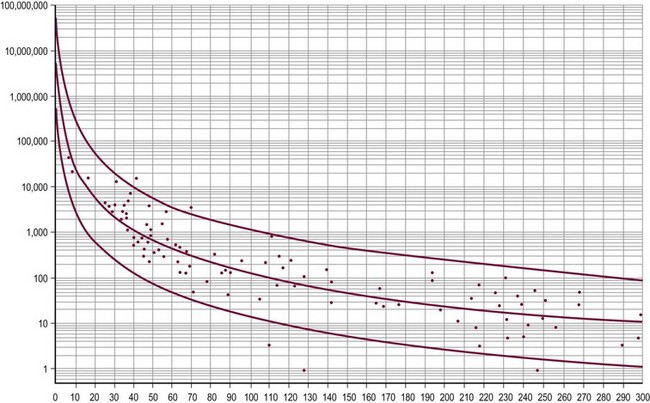

Though not pathognomonic, anechoic cystic lesions usually suggest benign disease. Internal calcifications and a mass with ‘onion-skin’ alternating hypo- and hyperechoic lesions suggests an epidermoid cyst.103 These findings may be useful in preoperative planning for testis-sparing surgery. Serum tumor marker levels are valuable not only in the diagnosis, but also follow-up of testicular malignancy. AFP is a glycoprotein produced by the fetal yolk sac, liver, and gastrointestinal tract. It is elevated in a variety of benign and malignant diseases, including YSTs of the testis. The half-life of AFP is approximately 5.5 days, and the normal adult level of less than 10 ng/mL is not achieved until around 10 months of age (Fig. 51-7).104 β-hCG is a glycoprotein produced by embryonal carcinomas and mixed teratomas. Its half-life is approximately 24 hours, and is normally not detected in significant amounts in boys (<5 IU/L).

FIGURE 51-7 This graph displays the normal ranges of serum α-fetoprotein (AFP) in early infancy. The AFP levels in nanograms per milliliter are on the y-axis and age in days is on the x-axis. The normal range for AFP may be estimated by the middle regression line. The two flanking lines represent the 95% confidence interval. (From Ohama K, Nagase H, Ogino K, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal children. Eur J Pediatr Surg 1997;7:267–9.)

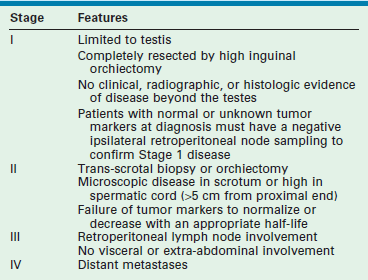

Once the diagnosis of high-risk testicular cancer is made histologically, CT can be used to evaluate metastatic disease. CT has largely supplanted RPLND for the purposes of staging; however, it carries a 15% to 20% false-negative rate.105 MRI also has been used, and it is probable that MRI will replace CT in children for diagnosis and follow-up due to the high ionizing radiation of CT and risk of future malignancy.106 Prepubertal testis tumors are staged using the Children’s Oncology Group staging system (Table 51-2).

TABLE 51-2

Children’s Oncology Group Staging System for Testicular Cancer

Adapted from Hayes-Lattin B, Nichols CR. Testicular cancer: a prototypic tumor of young adults. Semin Oncol 2009;36(5):432–8.

Carcinoma in Situ

CIS of the testis is a premalignant lesion. Testicular cancer is reported to develop in at least 50% of testes known to harbor CIS.65 CIS is seen in patients with UDT and intersex disorders, conditions that are known to carry a higher risk of testicular cancer than that in the general population.107 Testicular microlithiasis is associated with an increased risk of CIS as well as testicular germ cell tumors, but its presence in a testis is not considered premalignant. Rather, it seems to be a marker of increased risk of cancer in infertile men with atrophic testes or those with known testis cancer and microlithiasis in the contralateral testis.51,108 CIS is stimulated by endocrinologic changes during puberty. However, the natural history of CIS in prepubertal testes is less clear. When testicular biopsy at the time of orchiopexy is performed, CIS is seen in 0.36–0.45% of cases.77,109 The prevalence of CIS in adult men with a history of UDT is 2–4%.65,66 If CIS is identified in the prepubertal testis, it is typically managed with annual testicular examinations and testicular ultrasound. In postpubertal men, some clinicians recommend that these patients undergo biopsy of the contralateral testis and unilateral orchiectomy. If biopsy of the remaining testis also reveals CIS, they recommend 18–20 Gy of radiation treatment.110

Germ Cell Tumors

Yolk Sac Tumors

YSTs are also known as endodermal sinus tumors, embryonal adenocarcinomas, orchidoblastomas, or Teillum’s tumors. 111 Most occur within the first 2 years of life. Grossly, YSTs are firm and yellow/white. Microscopically, they are characterized by Schiller–Duval bodies and stain for AFP.112,113

Contrary to the behavior of embryonal carcinoma in adults, YST (which is histologically similar) in children has a more indolent course and spreads hematogenously. Approximately 95% of YSTs are confined to the testis, and metastases to the retroperitoneum are uncommon (5%).100 The lungs are the most common site of distant metastasis, and retroperitoneal metastases are seen only 5% of the time.101 The 5-year survival for YST approaches 99%.

Staging of YST requires abdominopelvic CT and chest radiography (CXR), histologic examination of the radical orchiectomy specimen, and determination of serum tumor markers. Stage I tumors are limited to the testis, and thus are usually cured by radical inguinal orchiectomy.114 Tumor markers are measured monthly and CXRs obtained every 2 months for the first 2 years. Abdominopelvic CT or MRI scans are obtained every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months for the second year. After 2 years without recurrence, follow-up may be extended to every 6 months or yearly.112

Traditionally, RPLND was recommended for boys with unknown or normal markers at diagnosis to confirm stage I disease. Although confirmatory RPLND may still be considered, it is used less often because stage 1 YST has a high likelihood of stage 1 presentation (85%), as propensity for hematogenous spread to the lungs, and because RPLND has a high complication rate in children. The risk of recurrence is approximately 20% and almost always can be salvaged with chemotherapy.101

Stage II disease includes those tumors with residual disease in the scrotum or high proximal cord, node involvement on imaging, or persistent elevation of tumor markers after orchiectomy. Tumors diagnosed and treated with trans-scrotal orchiectomy also should be considered stage II because transscrotal resection alters the normal lymphatic drainage of the tumor. Lymphatic drainage of the testis is to the retroperitoneal nodes, whereas the scrotum drains to the inguinal nodes. Ipsilateral hemiscrotectomy can also be considered. All patients with stage II disease should receive combination chemotherapy with cisplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin (PEB).101 Due to significant ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity with cisplatin, the UK Children’s Cancer Study Group substituted carboplatin for cisplatin, and were able to maintain a 100% event-free survival at 5 years.115 Patients with a persistent mass or elevated AFP after chemotherapy should undergo RPLND.

Stage III disease includes retroperitoneal spread (lymph node >4 cm) seen on imaging studies. Biopsy is used to confirm suspected nodal metastases, such as with lymph nodes >2 cm on CT. Metastasis beyond the retroperitoneum or to any viscera defines stage IV disease. For both stage III and stage IV disease, chemotherapy follows the same protocols as for stage II disease, followed by RPLND. The overall survival approaches 100%.100

Teratoma

Teratomas account for 40% of testicular tumors in prepubertal children. Histologically, teratomas are composed of all three layers of embryonic tissue: ectoderm, endoderm, and mesoderm. Grossly, they may contain differentiated tissue such as cartilage, muscle, bone, and fat; a cystic component also may be present. Before puberty, they follow a benign course and can be cured with testis-sparing surgery.116,117 Long-term mean follow-up of 7 years has demonstrated no tumor recurrence in the ipsilateral or contralateral gonad with a testis-sparing approach.117 Also, no radiographic follow-up has been recommended for prepubertal patients who undergo partial orchiectomy.101 If one accepts the dysplasia theory, however, whether benign or malignant, one might consider that a unilateral testicular tumor may pose an increased risk for the contralateral testis. On the other hand, when a child is seen at or after puberty, radical inguinal orchiectomy is indicated because the teratoma can follow a malignant postpubertal course.101

The enucleated tumor should always be sent for frozen section examination. If immature elements or pubertal changes are seen, radical orchiectomy should be performed. Overall disease-free survival after orchiectomy is excellent. 118 An elevated AFP or focus of YST may indicate potential recurrence. These patients can then be salvaged with platinum-based chemotherapy with 5-year survival rates in excess of 90%.119

Epidermoid cysts comprise about 15% of pediatric testis tumors, and as monodermal teratomas, follow a benign course. As such, a testis-sparing approach can be taken.101

Mixed Germ Cell Tumor

Teratocarcinoma, or mixed germ cell tumor, accounts for 20% of pediatric germ cell tumors. Teratocarcinoma is more commonly seen in an operatively corrected UDT and may contain any mixture of YST, embryonal carcinoma, choriocarcinoma, and seminoma.120 Eighty per cent of teratocarcinomas are confined to the testis at presentation. Foci of choriocarcinoma confer a poorer prognosis. RPLND is usually performed even for stage I disease, and higher-stage disease is treated with chemotherapy similar to those used for adults.

Nongerm Cell Tumors (Gonadal Stromal Tumors)

Leydig cell tumors are one of the most common nongerm cell tumors (NGCTs). The peak incidence in boys occurs from ages 5 to 9 years.101,122 The clinical triad includes a unilateral testicular mass (90–93%), precocious puberty, and elevated 17-ketosteroid levels. As these tumors produce testosterone and occasionally other androgens, roughly 20% of patients may have signs of precocious puberty and gynecomastia.123 Precocious puberty may also be caused by pituitary lesions, Leydig cell hyperplasia, and congenital adrenal hyperplasia so the pituitary/adrenal axis must be evaluated by assaying 17-ketosteroids, FSH, LH, and performing a dexamethasone suppression test. Reinke crystals on histologic examination are pathognomonic for this tumor and can be found in 35–40% of all patients.124 When diagnosed preoperatively, testis-sparing enucleation may be considered because these tumors tend to follow a benign course.125

The granulosa cell tumor also has a benign course and can be managed with testis-sparing surgery. This tumor should be suspected in neonates with scrotal swelling, normal age-adjusted AFP levels, and a complex, cystic, multiseptated, hypoechoic mass on testicular ultrasound.126

The Sertoli cell tumor is a rare form of NGCT. A small percentage of patients have gynecomastia, though these are typically not as hormonally active as Leydig cell tumors.127 The clinical course is usually benign in children under 5, and tumors can be managed with testis-sparing surgery. Older children, however, should have a metastatic evaluation with imaging.101

Gonadoblastoma is a form of NGCT usually associated with intersex disorders, occurring in dysgenetic gonads. The patients are typically 46XY phenotypic females (testicular feminization) with intra-abdominal testes who undergo virilization at puberty. Up to one-third of patients have bilateral gonadal lesions. The germ cell component of these tumors carries a 10% risk of malignant degeneration. Early gonadectomy is recommended, especially if the patient is raised as a female.128,129 Patients with mixed gonadal dysgenesis raised as males should have streak gonads and UDTs removed, though some suggest that scrotal testes can be preserved since they are less prone to malignancy and can be surveyed more easily.

Testicular Microlithiasis

Lastly, testicular microlithiasis may be seen in conjunction with testicular tumors (seen synchronously in 15–46% of patients), but is also seen incidentally in 5% of healthy young men. While the risk of testicular microlithiasis in children for the development of cancer is not well studied and reported numbers are small, there appear to be low-risk and high-risk individuals. Boys who have (1) atrophic or dystrophic testes; (2) known chromosomal abnormalities; (3) contralateral testis cancer, and possibly (4) history of UDT need closer follow-up with routine serial examination and scrotal ultrasound.130 Education about testicular self-examination is important for these patients.

References

1. Husmann, DA, Levy, JB. Current concepts in the pathophysiology of testicular undescent. Urology. 1995; 46:267–276.

2. Bardin, CW, Ross, GT, Rifkind, AB, et al. Studies of the pituitary-Leydig cell axis in young men with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and hyposmia: Comparison with normal men, prepubertal boys, and hypopituitary patients. J Clin Invest. 1969; 48:2046–2056.

3. Santen, RJ, Paulsen, CA. Hypogonadotropic eunuchoidism. II. Gonadal responsiveness to exogenous gonadotropins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973; 36:55–63.

4. Husmann, DA, McPhaul, MJ. Time-specific androgen blockade with flutamide inhibits testicular descent in the rat. Endocrinology. 1991; 129:1409–1416.

5. Spencer, JR, Torrado, T, Sanchez, RS, et al. Effects of flutamide and finasteride on rat testicular descent. Endocrinology. 1991; 129:741–748.

6. Emmen, JM, McLuskey, A, Adham, IM, et al. Involvement of insulin-like factor 3 (Insl3) in diethylstilbestrol-induced cryptorchidism. Endocrinology. 2000; 141:846–849.

7. Nef, S, Shipman, T, Parada, LF. A molecular basis for estrogen-induced cryptorchidism. Dev Biol. 2000; 15(224):354–361.

8. Fentener van Vlissingen, JM, van Zoelen, EJ, Ursem, PJ, et al. In vitro model of the first phase of testicular descent: identification of a low molecular weight factor from fetal testis involved in proliferation of gubernaculum testis cells and distinct from specified polypeptide growth factors and fetal gonadal hormones. Endocrinology. 1988; 123:2868–2877.

9. Heyns, CF, Hutson, JM. Historical review of theories on testicular descent. J Urol. 1995; 153:754–767.

10. Nef, S, Parada, LF. Cryptorchidism in mice mutant for Insl3. Nat Genet. 1999; 22:295–299.

11. Costa, WS, Sampaio, FJB, Favorito, LA, et al. Testicular migration: Remodeling of connective tissue and muscle cells in human gubernaculum testis. J Urol. 2002; 167:2171–2176.

12. Heyns, CF. The gubernaculum during testicular descent in the human fetus. J Anat. 1987; 153:93–112.

13. Barteczko, KJ, Jacob, MI. The testicular descent in human. Origin, development and fate of the gubernaculum Hunteri, processus vaginalis peritonei, and gonadal ligaments. Adv Anat Embryol Cell Biol. 2000; 156:III–X.

14. Goh, DW, Momose, Y, Middlesworth, W, et al. The relationship among calcitonin gene-related peptide, androgens and gubernacular development in 3 animal models of cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1993; 150:574–576.

15. Park, WH, Hutson, JM. The gubernaculum shows rhythmic contractility and active movement during testicular descent. J Pediatr Surg. 1991; 26:615–617.

16. Hutson, JM, Nation, T, Balic, A, et al. The role of the gubernaculum in the descent and undescent of the testis. Ther Adv Urol. 2009; 1:115–121.

17. Elder, JS. Epididymal anomalies associated with hydrocele/hernia and cryptorchidism: Implications regarding testicular descent. J Urol. 1992; 148:624–626.

18. Gill, B, Kogan, S, Starr, S, et al. Significance of epididymal and ductal anomalies associated with testicular maldescent. J Urol. 1989; 142:556–558.

19. Hadziselimovic, F, Herzog, B. The development and descent of the epididymis. Eur J Pediatr. 1993; 152(Suppl 2):S6–S9.

20. Kaplan, GW. Nomenclature of cryptorchidism. Eur J Pediatr. 1993; 152(Suppl 2):S17–S19.

21. Agarwal, PK, Diaz, M, Elder, JS. Retractile testis–is it really a normal variant? J Urol. 2006; 175:1496–1499.

22. Singh, R, Hamada, AJ, Bukavina, L, et al. Physical deformities relevant to male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2012; 9:156–174.

23. Stec, AA, Thomas, JC, DeMarco, RT, et al. Incidence of testicular ascent in boys with retractile testes. J Urol. 2007; 178:1722–1725.

24. Sijstermans, K, Hack, WWM, Meijer, RW, et al. The frequency of undescended testis from birth to adulthood: A review. Int J Androl. 2008; 31:1–11.

25. Pohl, H. The location and fate of the cryptorchid and impalpable testes. Dialogues in Pediatric Urology. Pearl River, NY: William J. Miller Associates; 1997.

26. Capello, SA, Giorgi, LJ, Jr., Kogan, BA. Orchiopexy practice patterns in New York State from 1984 to 2002. J Urol. 2006; 176:1180–1183.

27. Hack, WWM, Meijer, RW, Van Der Voort-Doedens, LM, et al. Previous testicular position in boys referred for an undescended testis: Further explanation of the late orchidopexy enigma? BJU Int. 2003; 92:293–296.

28. Barthold, JS, González, R. The epidemiology of congenital cryptorchidism, testicular ascent and orchiopexy. J Urol. 2003; 170:2396–2401.

29. Guven, A, Kogan, BA. Undescended testis in older boys: Further evidence that ascending testes are common. J Pediatr Surg. 2008; 43:1700–1704.

30. Docimo, SG. The results of surgical therapy for cryptorchidism: A literature review and analysis. J Urol. 1995; 154:1148–1152.

31. Kirsch, AJ, Escala, J, Duckett, JW, et al. Surgical management of the nonpalpable testis: The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia experience. J Urol. 1998; 159:1340–1343.

32. Jarow, JP, Berkovitz, GD, Migeon, CJ, et al. Elevation of serum gonadotropins establishes the diagnosis of anorchism in prepubertal boys with bilateral cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1986; 136:277–279.

33. Esposito, C, Cardona, R, Centonze, A, et al. Impact of laparoscopy on the management of an unusual case of nonpalpable testis in an adult patient. Surg Endosc. 2003; 17:1324.

34. De Filippo, RE, Barthold, JS, González, R. The application of magnetic resonance imaging for the preoperative localization of nonpalpable testis in obese children: An alternative to laparoscopy. J Urol. 2000; 164:154–155.

35. Landa, HM, Gylys-Morin, V, Mattrey, RF, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cryptorchid testis. Eur J Pediatr. 1987; 146(Suppl 2):S16–S17.

36. Elder, JS. Ultrasonography is unnecessary in evaluating boys with a nonpalpable testis. Pediatrics. 2002; 110:748–751.

37. Tasian, GE, Copp, HL, Baskin, LS. Diagnostic imaging in cryptorchidism: Utility, indications, and effectiveness. J Pediatr Surg. 2011; 46:2406–2413.

38. Snodgrass, W, Bush, N, Holzer, M, et al. Current referral patterns and means to improve accuracy in diagnosis of undescended testis. Pediatrics. 2011; 127:e382–e388.

39. Huff, DS, Hadziselimovic, F, Snyder, HM, 3rd., et al. Histologic maldevelopment of unilaterally cryptorchid testes and their descended partners. Eur J Pediatr. 1993; 152(Suppl 2):S11–S14.

40. Rusnack, SL, Wu, H-Y, Huff, DS, et al. Testis histopathology in boys with cryptorchidism correlates with future fertility potential. J Urol. 2003; 169:659–662.

41. Puri, P, O’Donnell, B. Semen analysis of patients who had orchidopexy at or after seven years of age. Lancet. 1988; 5(2):1051–1052.

42. Lee, PA, Coughlin, MT, Bellinger, MF. Paternity and hormone levels after unilateral cryptorchidism: association with pretreatment testicular location. J Urol. 2000; 164:1697–1701.

43. Lee, PA. Fertility in cryptorchidism. Does treatment make a difference? Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1993; 22:479–490.

44. Chilvers, C, Dudley, NE, Gough, MH, et al. Undescended testis: The effect of treatment on subsequent risk of subfertility and malignancy. J Pediatr Surg. 1986; 21:691–696.

45. Lee, PA, Coughlin, MT. The single testis: paternity after presentation as unilateral cryptorchidism. J Urol. 2002; 168:1680–1683.

46. Lee, PA, Coughlin, MT. Fertility after bilateral cryptorchidism. Evaluation by paternity, hormone, and semen data. Horm Res. 2001; 55:28–32.

47. Lee, PA, O’Leary, LA, Songer, NJ, et al. Paternity after bilateral cryptorchidism. A controlled study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997; 151:260–263.

48. Hadziselimovic, F, Thommen, L, Girard, J, et al. The significance of postnatal gonadotropin surge for testicular development in normal and cryptorchid testes. J Urol. 1986; 136(1 Pt 2):274–276.

49. Mizuno, K, Hayashi, Y, Kojima, Y, et al. Early orchiopexy improves subsequent testicular development and spermatogenesis in the experimental cryptorchid rat model. J Urol. 2008; 179:1195–1199.

50. Kollin, C, Karpe, B, Hesser, U, et al. Surgical treatment of unilaterally undescended testes: Testicular growth after randomization to orchiopexy at age 9 months or 3 years. J Urol. 2007; 178:1589–1593.

51. Jaganathan, K, Ahmed, S, Henderson, A, et al. Current management strategies for testicular microlithiasis. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2007; 4:492–497.

52. Schwentner, C, Oswald, J, Kreczy, A, et al. Neoadjuvant gonadotropin-releasing hormone therapy before surgery may improve the fertility index in undescended testes: A prospective randomized trial. J Urol. 2005; 173:974–977.

53. Herrinton, LJ, Zhao, W, Husson, G. Management of cryptorchism and risk of testicular cancer. Am J Epidemiol. 2003; 1(157):602–605.

54. Li, FP, Fraumeni, JF. Testicular cancers in children: Epidemiologic characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1972; 48:1575–1581.

55. Ross, JH, Rybicki, L, Kay, R. Clinical behavior and a contemporary management algorithm for prepubertal testis tumors: A summary of the Prepubertal Testis Tumor Registry. J Urol. 2002; 168:1675–1679.

56. Wood, HM, Elder, JS. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer: Separating fact from fiction. J Urol. 2009; 181:452–461.

57. Raja, MA, Oliver, RT, Badenoch, D, et al. Orchidopexy and transformation of seminoma to non-seminoma. Lancet. 1992; 339:930.

58. Halme, A, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen, P, Lehtonen, T, et al. Morphology of testicular germ cell tumours in treated and untreated cryptorchidism. Br J Urol. 1989; 64:78–83.

59. Jones, BJ, Thornhill, JA, O’Donnell, B, et al. Influence of prior orchiopexy on stage and prognosis of testicular cancer. Eur Urol. 1991; 19:201–203.

60. Pike, MC, Chilvers, C, Peckham, MJ. Effect of age at orchidopexy on risk of testicular cancer. Lancet. 1986; 31(1):1246–1248.

61. Pettersson, A, Richiardi, L, Nordenskjold, A, et al. Age at surgery for undescended testis and risk of testicular cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007; 3(356):1835–1841.

62. Walsh, TJ, Dall’Era, MA, Croughan, MS, et al. Prepubertal orchiopexy for cryptorchidism may be associated with lower risk of testicular cancer. J Urol. 2007; 178:1440–1446.

63. Asklund, C, Jørgensen, N, Kold Jensen, T, et al. Biology and epidemiology of testicular dysgenesis syndrome. BJU Int. 2004; 93(Suppl 3):6–11.

64. Akre, O, Pettersson, A, Richiardi, L. Risk of contralateral testicular cancer among men with unilaterally undescended testis: a meta-analysis. Int J Cancer. 2009; 1(124):687–689.

65. Dieckmann, KP, Skakkebaek, NE. Carcinoma in situ of the testis: Review of biological and clinical features. Int J Cancer. 1999; 10(83):815–822.

66. Giwercman, A, Müller, J, Skakkebaek, NE. Cryptorchidism and testicular neoplasia. Horm Res. 1988; 30:157–163.

67. Timing of elective surgery on the genitalia of male children with particular reference to the risks, benefits, and psychological effects of surgery and anesthesia. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 1996; 97:590–594.

68. Tekgul, S. Guidelines on Paediatric Urology. European Association of Urology; 2012.

69. Kokorowski, PJ, Routh, JC, Graham, DA, et al. Variations in timing of surgery among boys who underwent orchidopexy for cryptorchidism. Pediatrics. 2010; 126:e576–e582.

70. Bica, DT, Hadziselimovic, F. Buserelin treatment of cryptorchidism: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Urol. 1992; 148:617–621.

71. Hadziselimovi ;, F, Huff, D, Duckett, J, et al. Long-term effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue (buserelin) on cryptorchid testes. J Urol. 1987; 138:1043–1045.

;, F, Huff, D, Duckett, J, et al. Long-term effect of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analogue (buserelin) on cryptorchid testes. J Urol. 1987; 138:1043–1045.

72. Lala, R, Matarazzo, P, Chiabotto, P, et al. Early hormonal and surgical treatment of cryptorchidism. J Urol. 1997; 157:1898–1901.

73. Lala, R, Matarazzo, P, Chiabotto, P, et al. Combined therapy with LHRH and HCG in cryptorchid infants. Eur J Pediatr. 1993; 152(Suppl 2):S31–S33.

74. Giannopoulos, MF, Vlachakis, IG, Charissis, GC. 13 Years’ experience with the combined hormonal therapy of cryptorchidism. Horm Res. 2001; 55:33–37.

75. Waldschmidt, J, Doede, T, Vygen, I. The results of 9 years of experience with a combined treatment with LH-RH and HCG for cryptorchidism. Eur J Pediatr. 1993; 152(Suppl 2):S34–S36.

76. Elder, JS. Why do our colleagues still image for cryptorchidism? Ignoring the evidence. J Urol. 2011; 185:1566–1567.

77. Hadziselimovi ;, F, Hecker, E, Herzog, B. The value of testicular biopsy in cryptorchidism. Urol Res. 1984; 12:171–174.

;, F, Hecker, E, Herzog, B. The value of testicular biopsy in cryptorchidism. Urol Res. 1984; 12:171–174.

78. Esposito, C, Damiano, R, Gonzalez Sabin, MA, et al. Laparoscopy-assisted orchidopexy: An ideal treatment for children with intra-abdominal testes. J Endourol. 2002; 16:659–662.

79. Benson, CD, Lotfi, MW. The pouch technique in the surgical correction of cryptorchidism in infants and children. Surgery. 1967; 62:967–973.

80. Koop, CE. Technique of herniorrhaphy and orchidopexy. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1977; 13:293–303.

81. Bassel, YS, Scherz, HC, Kirsch, AJ. Scrotal incision orchiopexy for undescended testes with or without a patent processus vaginalis. J Urol. 2007; 177:1516–1518.

82. Rajfer, J. Technique of orchiopexy. Urol Clin North Am. 1982; 9(3):421–427.

83. Saw, KC, Eardley, I, Dennis, MJ, et al. Surgical outcome of orchiopexy. I. Previously unoperated testes. Br J Urol. 1992; 70:90–94.

84. Dayanc, M, Kibar, Y, Irkilata, HC, et al. Long-term outcome of scrotal incision orchiopexy for undescended testis. Urology. 2007; 70(4):786–789.

85. Redman, JF, Barthold, JS. A technique for atraumatic scrotal pouch orchiopexy in the management of testicular torsion. J Urol. 1995; 154:1511–1512.

86. Coughlin, MT, Bellinger, MF, LaPorte, RE, et al. Testicular suture: A significant risk factor for infertility among formerly cryptorchid men. J Pediatr Surg. 1998; 33:1790–1793.

87. Bellinger, MF, Abromowitz, H, Brantley, S, et al. Orchiopexy: An experimental study of the effect of surgical technique on testicular histology. J Urol. 1989; 142:553–555.

88. Al-Mandil, M, Khoury, AE, El-Hout, Y, et al. Potential complications with the prescrotal approach for the palpable undescended testis? A comparison of single prescrotal incision to the traditional inguinal approach. J Urol. 2008; 180:686–689.

89. Esposito, C, Caldamone, AA, Settimi, A, et al. Management of boys with nonpalpable undescended testis. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2008; 5:252–260.

90. Cisek, LJ, Peters, CA, Atala, A, et al. Current findings in diagnostic laparoscopic evaluation of the nonpalpable testis. J Urol. 1998; 160:1145–1150.

91. Merguerian, PA, Mevorach, RA, Shortliffe, LD, et al. Laparoscopy for the evaluation and management of the nonpalpable testicle. Urology. 1998; 51:3–6.

92. Lindgren, BW, Franco, I, Blick, S, et al. Laparoscopic Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy for the high abdominal testis. J Urol. 1999; 162(3 Pt 2):990–994.

93. Fowler, R, Stephens, FD. The role of testicular vascular anatomy in the salvage of high undescended testes. Aust N Z J Surg. 1959; 29:92–106.

94. Law, GS, Pérez, LM, Joseph, DB. Two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy with laparoscopic clipping of the spermatic vessels. J Urol. 1997; 158:1205–1207.

95. Chang, B, Palmer, LS, Franco, I. Laparoscopic orchidopexy: A review of a large clinical series. BJU Int. 2001; 87(6):490–493.

96. Radmayr, C, Oswald, J, Schwentner, C, et al. Long-term outcome of laparoscopically managed nonpalpable testes. J Urol. 2003; 170:2409–2411.

97. Baker, LA, Docimo, SG, Surer, I, et al. A multi-institutional analysis of laparoscopic orchidopexy. BJU Int. 2001; 87(6):484–489.

98. Cartwright, PC, Velagapudi, S, Snyder, HM, 3rd., et al. A surgical approach to reoperative orchiopexy. J Urol. 1993; 149:817–818.

99. Pohl, HG, Shukla, AR, Metcalf, PD, et al. Prepubertal testis tumors: Actual prevalence rate of histological types. J Urol. 2004; 172:2370–2372.

100. Wu, HY, Snyder, HM, 3rd. Pediatric urologic oncology: Bladder, prostate, testis. Urol Clin North Am. 2004; 31:619–627.

101. Agarwal, PK, Palmer, JS. Testicular and paratesticular neoplasms in prepubertal males. J Urol. 2006; 1176:875–881.

102. Walsh, TJ, Grady, RW, Porter, MP, et al. Incidence of testicular germ cell cancers in USA children: SEER program experience 1973 to 2000. Urology. 2006; 68:402–405.

103. Langer, JE, Ramchandani, P, Siegelman, ES, et al. Epidermoid cysts of the testicle: Sonographic and MR imaging features. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999; 173:1295–1299.

104. Ohama, K, Nagase, H, Ogino, K, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal children. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1997; 7:267–269.

105. Pizzocaro, G, Zanoni, F, Salvioni, R, et al. Difficulties of a surveillance study omitting retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy in clinical stage I nonseminomatous germ cell tumors of the testis. J Urol. 1987; 138:1393–1396.

106. Cho, J-H, Chang, J-C, Park, B-H, et al. Sonographic and MR imaging findings of testicular epidermoid cysts. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002; 178:743–748.

107. Wallace, TM, Levin, HS. Mixed gonadal dysgenesis. A review of 15 patients reporting single cases of malignant intratubular germ cell neoplasia of the testis, endometrial adenocarcinoma, and a complex vascular anomaly. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990; 14:679–688.

108. van Casteren, NJ, Looijenga, LHJ, Dohle, GR. Testicular microlithiasis and carcinoma in situ overview and proposed clinical guideline. Int J Androl. 2009; 32:279–287.

109. Cortes, D, Thorup, JM, Visfeldt, J. Cryptorchidism: aspects of fertility and neoplasms. A study including data of 1,335 consecutive boys who underwent testicular biopsy simultaneously with surgery for cryptorchidism. Horm Res. 2001; 55:21–27.

110. Heidenreich, A, Moul, JW. Contralateral testicular biopsy procedure in patients with unilateral testis cancer: Is it indicated? Semin Urol Oncol. 2002; 20:234–238.

111. Kay, R. Prepubertal Testicular Tumor Registry. J Urol. 1993; 150:671–674.

112. Wu, HY, Snyder, HM. Advances in Pediatric Urologic Oncology. AUA Update Series XXII. 2003.

113. Wold, LE, Kramer, SA, Farrow, GM. Testicular yolk sac and embryonal carcinomas in pediatric patients: Comparative immunohistochemical and clinicopathologic study. Am J Clin Pathol. 1984; 81:427–435.

114. Hayes-Lattin, B, Nichols, CR. Testicular cancer: A prototypic tumor of young adults. Semin Oncol. 2009; 36:432–438.

115. Mann, JR, Raafat, F, Robinson, K, et al. The United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group’s second germ cell tumor study: Carboplatin, etoposide, and bleomycin are effective treatment for children with malignant extracranial germ cell tumors, with acceptable toxicity. J Clin Oncol. 2000; 15(18):3809–3818.

116. Rushton, HG, Belman, AB, Sesterhenn, I, et al. Testicular sparing surgery for prepubertal teratoma of the testis: A clinical and pathological study. J Urol. 1990; 144:726–730.

117. Shukla, AR, Woodard, C, Carr, MC, et al. Experience with testis sparing surgery for testicular teratoma. J Urol. 2004; 171:161–163.

118. Marina, NM, Cushing, B, Giller, R, et al. Complete surgical excision is effective treatment for children with immature teratomas with or without malignant elements: A Pediatric Oncology Group/Children’s Cancer Group Intergroup Study. J Clin Oncol. 1999; 17:2137–2143.

119. Mann, JR, Gray, ES, Thornton, C, et al. Mature and immature extracranial teratomas in children: The UK Children’s Cancer Study Group Experience. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 20(26):3590–3597.

120. Batata, MA, Whitmore, WF, Jr., Chu, FC, et al. Cryptorchidism and testicular cancer. J Urol. 1980; 124:382–387.

121. Perry, C, Servadio, C. Seminoma in childhood. J Urol. 1980; 124:932–933.

122. Coppes, MJ, Rackley, R, Kay, R. Primary testicular and paratesticular tumors of childhood. Med Pediatr Oncol. 1994; 22:329–340.

123. Cheville, JC, Sebo, TJ, Lager, DJ, et al. Leydig cell tumor of the testis: A clinicopathologic, DNA content, and MIB-1 comparison of nonmetastasizing and metastasizing tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998; 22:1361–1367.

124. Jain, M, Aiyer, HM, Bajaj, P, et al. Intracytoplasmic and intranuclear Reinke’s crystals in a testicular Leydig-cell tumor diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration cytology: A case report with review of the literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2001; 25:162–164.

125. Henderson, CG, Ahmed, AA, Sesterhenn, I, et al. Enucleation for prepubertal Leydig cell tumor. J Urol. 2006; 176:703–705.

126. Shukla, AR, Huff, DS, Canning, DA, et al. Juvenile granulosa cell tumor of the testis: Contemporary clinical management and pathological diagnosis. J Urol. 2004; 171:1900–1902.

127. Gabrilove, JL, Freiberg, EK, Leiter, E, et al. Feminizing and non-feminizing Sertoli cell tumors. J Urol. 1980; 124:757–767.

128. Gourlay, WA, Johnson, HW, Pantzar, JT, et al. Gonadal tumors in disorders of sexual differentiation. Urology. 1994; 43:537–540.

129. Olsen, MM, Caldamone, AA, Jackson, CL, et al. Gonadoblastoma in infancy: Indications for early gonadectomy in 46XY gonadal dysgenesis. J Pediatr Surg. 1988; 23:270–271.

130. Dagash, H, Mackinnon, EA. Testicular microlithiasis: What does it mean clinically? BJU Int. 2007; 99:157–160.