UNDERWATER DIVING ACCIDENTS AND DROWNING

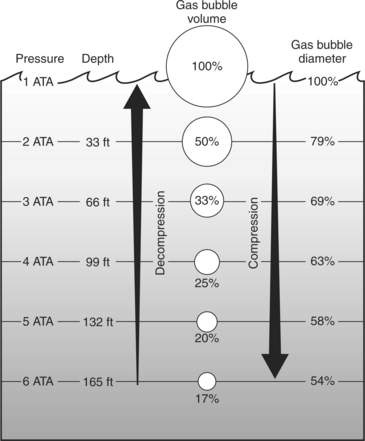

On land at sea level, the human body is constantly exposed to 14.7 lb (6.7 kg, or 1 atmosphere) of pressure from the weight of the atmosphere (an air column 165 miles, or 266 km, high). As a human descends under water in the ocean, with every 33 ft (13 m) of depth an additional atmosphere of pressure is exerted. With increasing pressure (P) that occurs on descent, the volume (V) of gas in an enclosed space is diminished, as determined by Boyle’s law: P1V1 = P2. Conversely, during ascent from the depths, the gas in an enclosed space expands. Under water, the greatest relative volume changes with increasing and decreasing pressure occur near the surface (Figure 216).

AIR EMBOLISM

An air embolism occurs when there is a rupture in the barrier between the microscopic air space of a lung and its corresponding blood vessel, which carries oxygenated blood back to the heart (where it can be distributed to the body). In effect, bubbles of air are released into the arterial bloodstream, where they act as physical barriers to circulation, and can cause a stroke (see page 144), heart attack (see page 50), headache, and/or confusion. Typically, the victim is a scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus) diver who ascends too rapidly without exhaling, thus allowing overexpansion of the lungs—and rupture of the tissue—as the external water pressure decreases with ascent. In other words, as a diver ascends from the depths, the air in his lungs (which was delivered from the scuba tank through a regulator at a pressure equal to the surrounding water pressure on the lungs, thereby allowing lung expansion) expands. If the rate of exhalation does not keep pace with the lung expansion, the increased pressure within the lungs causes air to be forced through the lung tissue, where it appears in the bloodstream in bubble form and travels directly to the heart. From the heart, the air circulates to and may occlude critical small blood vessels that supply the heart, brain, and spinal cord.

Anyone suspected of having suffered an air embolism should be placed in a head-down position (with the body at a 15- to 30-degree tilt), turned onto his left side, assisted with breathing if necessary (see page 29), and immediately transported to an emergency facility. If oxygen (see page 431) is available, it should be administered by facemask at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute. The treatment for arterial gas embolism is recompression in a hyperbaric oxygen chamber, which pressurizes the victim’s environment and shrinks the bubbles. This must be accomplished as rapidly as possible to save the victim’s life and to minimize disability. A portable recompression chamber manned by trained personnel may be used to initiate field treatment. If the victim is capable of purposeful swallowing, administer one adult aspirin by mouth.

If the air that expands on ascent does not rupture into a blood vessel and become an air embolism, it can rupture into the actual lung tissues or into the pleural space between the lung and the inside of the chest wall, and cause a collapsed lung (pneumothorax) (see page 41). Other symptoms include air that escapes into the soft tissues, so that there is swelling of the chest and neck, and sometimes a “Rice Krispies” feel to the skin. If the air dissects into the neck, it can cause hoarseness, difficulty swallowing, and sore throat. In this case, oxygen administration is advised. Recompression in a hyperbaric chamber is not advised for a pneumothorax unless there are also severe symptoms associated with an air embolism.

DECOMPRESSION SICKNESS (THE “BENDS”)

The signs and symptoms caused by these bubbles in the body represent decompression sickness, also known as the “bends.” Symptoms may begin immediately after ascent from a dive or may be delayed by a number of hours. These include deep boring joint pain without swelling-warmth-redness, numbness and tingling of the arms and legs, difficulty walking, back pain, fatigue, weakness, inability to control the bladder or bowels (spinal cord “hit”), paralysis, double vision, diminished vision, headache, confusion, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, difficulty in speaking, itching, skin mottling (“marbling”), shortness of breath, cough, and collapse. A rapid, simplified neurologic exam (see page 145), such as administered to a suspected stroke victim, may identify a subtle abnormality.

If you suspect someone of suffering the bends, immediately have him begin to breathe oxygen (at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute by facemask) (see page 431) and begin rapid transport to an emergency facility. Oxygen breathing should occur for at least 30 minutes. The definitive treatment is recompression in a hyperbaric chamber. Do not put the diver back into the water to attempt in-water recompression; this can be very hazardous. If possible, have the victim lie down in a comfortable position, preferably on his side, but do not let him obstruct blood flow to a limb by resting his head on an arm or crossing his legs. A portable recompression chamber manned by trained personnel may be used to initiate field treatment.

EAR SQUEEZE

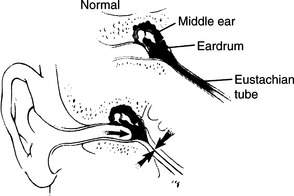

As a diver descends in the water, the external water pressure on his eardrum increases rapidly. If he cannot equalize this pressure from within by forcing air into the eustachian tube (a small passageway that connects the middle ear and the throat) and into the middle ear, the eardrum stretches inward (extremely painful) and then ruptures (Figure 217). This rupture allows water to rush into the middle ear, with resultant severe pain, hearing loss, vertigo (see page), nausea, vomiting, and disorientation. If the diver cannot make his way to the surface, he may drown. If the eardrum is injured but not ruptured, the pain is similar to that of an ear infection. In this situation, the eardrum is intact, but tissue fluid and blood have collected in the middle ear, partially or completely filling it. In addition to pain, the victim notes decreased hearing, and a sense of fullness in the ear. If this occurs, diving should be prohibited (see below) and the person treated with decongestants and, in a severe case, with prednisone (begin with 60 mg first dose for an adult and decrease by 10 mg each day for 5 days) to decrease inflammation.

If a diver suddenly feels pain in his ear and is stricken with dizziness, nausea, or visual difficulty, he should remain calm and slowly ascend to the surface. The ear should be allowed to drain and dry on its own. Do not insert cotton swabs into the ear, because you may poke the eardrum and increase the damage. Do not instill any medicines into the ear, unless you are carrying ofloxacin otic solution 0.3% or Cortisporin suspension (not “solution”). Transport the victim to an ear specialist. Suspend all diving activities until the eardrum is healed or repaired. If dizziness is profound, administer a drug(s) for motion sickness (see page 440). The victim should be started on an antibiotic (ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, or doxycycline) to oppose Vibrio bacteria. If one of these antibiotics is not available, use amoxicillin-clavulanate. An oral or topical nasal decongestant (such as 0.5% oxymetazoline) is useful for the first few days after the episode. Because sudden dizziness may also be due to an air embolism or the bends, the victim should be observed closely for worsening of his condition.

Alternobaric vertigo refers to a condition where the pressure in the middle ear can be different between the two ears, usually on ascent. This may cause a person to suffer from vertigo of relatively short duration, ringing in the ears, and hearing loss. The treatment is patience until the pressures in middle ears equalize; decongestants may help hasten the process.

SINUS SQUEEZE

If a sinus squeeze occurs, slowly ascend to the surface. This generally alleviates most of the pain, but it may take a while for the bleeding to stop. Because the sinus may now be blood-filled, the victim is at high risk for developing sinusitis (see page 194) and should be placed on amoxicillin-clavulanate or azithromycin for 4 days, along with oral and nasal decongestants to promote drainage. If the pain is severe and persists for more than 12 hours after the initial incident, the victim may benefit from a short course of prednisone: 60 mg the first day, 40 mg the second, and 20 mg the third. This combats the inflammation, but should not be given if the victim has symptoms of a sinus infection (foul nasal discharge, fever, facial tenderness).

DROWNING (SUBMERSION/IMMERSION INTO LIQUID)

1. Lack of oxygen. If death occurs during the drowning episode, it is most likely because of suffocation due to being submerged or immersed in water. Another factor is spasm of the vocal cords, which blocks the passage of air through the windpipe (most commonly seen in cold-water drowning). When submerged, the body is starved of oxygen, which is essential to survival. If the submersion lasts long enough, the victim loses consciousness and ultimately suffers a cardiac arrest. If death occurs in a delayed fashion, it is because the lung tissue is injured by water, and oxygen transfer into the bloodstream is inhibited, which commonly leads to brain injury and other organ failure.

2. Body chemistry abnormalities. Because of the lack of oxygen delivery to the organs and tissues of the body, there is rapid accumulation of waste products that cannot be effectively removed. This results in an accumulation of acid and other chemicals that alter the function of the heart, brain, kidneys, liver, and so on.

3. Accompanying problems, such as hypothermia (see page 305), injuries, and serious illnesses (for example, heart attack or stroke). Sadly, alcohol figures prominently in adult boating and drowning accidents.

If a drowning incident occurs, do the following:

1. Remove the victim from the water, while ensuring that you and others remain safe. If immediate rescue is difficult or impossible, and at the earliest opportunity, send someone for help.

2. Check for breathing by feeling over the mouth and nose while watching the chest rise. Open the mouth and sweep it clean with two fingers. Align the victim on the ground with his head at a level below his feet. Begin mouth-to-mouth or mouth–to–mouth-and-nose (for a child) breathing, if necessary (see page 29).

3. Check for pulses and begin chest compressions if necessary (see page 32).

4. Suspect a broken neck in the appropriate circumstances. For instance, someone who has been seen to collapse in a swimming pool probably hasn’t broken his neck. (If he dove into the pool, that’s another story!) However, someone who tumbles into the waves off a surfboard and washes up unconscious onto the beach may well have a neck injury. Do what is necessary to aid the victim, but remember to protect his neck (see page 37).

5. The Heimlich maneuver (see page 27) is not recommended for use in the rescue of drowning victims, because it may cause the victim to regurgitate and inhale his or her vomit. A few rescuers have observed that if the victim is nonbreathing and in the water, where mouth-to-mouth breathing is difficult or impractical, a few brisk “hugs” applied to the chest (not the stomach) may stimulate the victim to cough and begin breathing on his own.

6. Hypothermia (see page 305) is commonly associated with drowning. Cover the victim above and below with blankets. Gently remove all wet clothing. Because hypothermia may be protective for the heart and brain (with regard to lack of oxygen) to a considerable degree, if the victim is cold, continue the resuscitation until trained rescuers arrive or until you are fatigued. Remember, “no one is dead until he is warm and dead.”

7. If the victim responds to your measures, he should be transported to an emergency facility. Even if he feels 100% normal, he should still be evaluated by a physician, because delayed worsening of lung function is possible. A person who is already short of breath and coughing may deteriorate quickly.

8. Administer oxygen (see page 431) at a flow rate of 10 liters per minute by face mask.

Prevention of Drowning

1. Watch your children. Toddlers are at greatest risk for near-drowning.

2. Fence in all pools and swimming areas. Maintain the water level in a pool as high as possible to allow a person who reaches the edge to pull himself out.

3. Teach children to swim, but be advised that such teaching does not “drown-proof” a child. In other words, never let a small child out of your sight when he or she is near the water, even if they know how to swim. In a drowning situation, they may not have the body strength, judgment, or emotional reserve to allow self rescue. Furthermore, new swimmers and children may have a false sense of security and take undue risks after being taught how to swim.

4. Never place nonswimmers in high-risk situations: small sailboats, whitewater rafts, inflatable kayaks, and the like.

5. When boating or rafting, always wear a properly rated life vest with a snug fit and a head flotation collar. In a kayak or raft traversing whitewater, wear a proper helmet.

6. Do not mix alcohol and water sports.

7. Know your limits. Feats of endurance and demonstrations of bravado in dangerous rapids or surf are for idiots.

8. Be prepared for a flash flood. In times of unusually heavy rainfall, stay away from natural streambeds, arroyos, and other drainage channels. Use a map to determine your elevation, and stay off low ground or the very bottom of a hill. Know where the high ground is and how to get there in a hurry. Absolutely avoid flooded areas and unnecessary stream and river crossings. Do not attempt to cross a flowing stream where the water is above your knees. Abandon a stalled vehicle in a flood area.