4 Understanding the Illness Experience and Providing Anticipatory Guidance

Matthew was a red-haired little boy suffering from congenital microvillus inclusion disease, an autosomal recessive disorder that is characterized by intestinal failure and often treated with multivisceral organ transplantation. This patient and his family experienced a great deal of suffering. When he was 5 years old, after a year-long hospitalization and careful consideration of prognosis and establishment of realistic goals of care, his family decided to bring him home despite concerns for the complexity of his care. He was discharged on multiple medications including continuous opioid infusion and parenteral nutrition under the care of the local hospice and palliative care team. Medical care continued at home as an integral aspect of a normal family life. His last months included a trip to a Nascar race, visits by a local fireman, and a full array of school services. Most importantly he was wrapped in the love of his two sisters, parents, and grandparents through his death (Figs. 4-1 to 4-3).

Establishing a Therapeutic Alliance

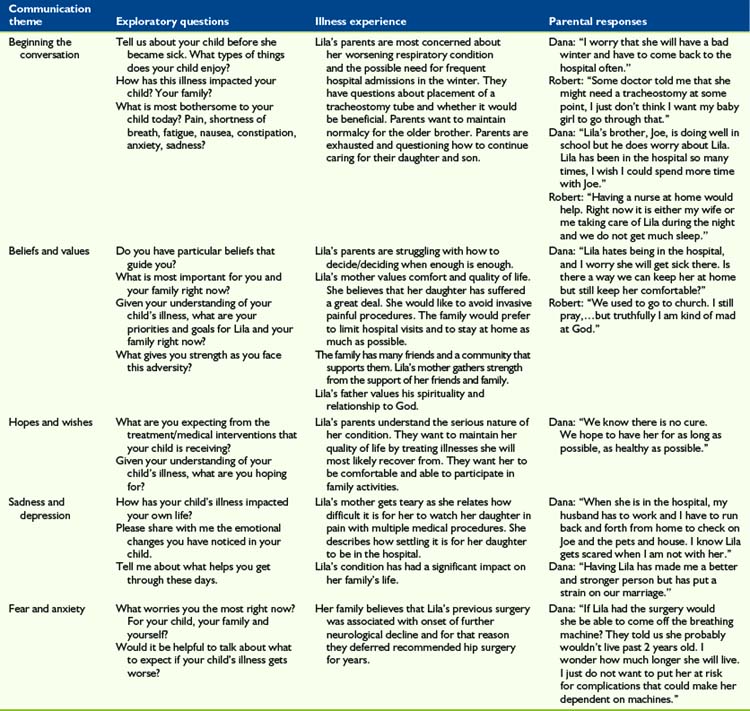

Understanding the patient’s and family’s beliefs, values, hopes, wishes, expectations, fears, and worries is crucial for clinicians who strive to create a plan of care with their patients. Clinicians must be willing to listen, empathize, solve problems, and encourage life-affirming events with patients and families as they face the challenges associated with a life-threatening illness. Misunderstandings and frustrations more often occur when clinicians offer treatment options without understanding the feelings, thoughts, and underlying themes that guide the patient’s and family’s decision-making process. A sample of exploratory responses that may be used in communicating with children and families is included in Table 4-1.

An essential part of establishing a therapeutic alliance is regular meetings with the patient and his or her family in which issues outlined in this chapter are discussed. Such discussions should be planned with care. For example, adequate time for in-depth conversation should be allotted, a private setting should be arranged, and the presence of both parents and/or others who are identified as primary supporters should be ensured. By listening respectfully and building on the parents’ knowledge, the interdisciplinary team (IDT)—which is typically composed of doctors, nurses, social workers, child life specialists, chaplains, and psychologists—can tailor information and educate the family about treatment options and other issues of relevance. Recommendations may be made based on the existing evidence, on realistic goals, and within the child’s and family’s psychosocial and spiritual context. Elements of anticipatory guidance in the palliative care setting are discussed in the following section and suggested themes are presented in Box 4-1.

Advanced Illness Care Planning

Ethical and Legal Considerations

Symptom Control

Care Coordination and Continuity

Understanding the Illness Experience

Beliefs and values

Beliefs and values give meaning to a person’s life. They influence the patient’s and family’s perceptions about how things are and how things should be. Values may dictate preferences in some circumstances. Patients with life-threatening conditions and their parents apply a set of values to guide decisions about medical care.1,2 Decisions made by patients and families about whether a certain treatment is desirable are often based on their determination of the treatment’s positive or negative qualities and whether it is perceived as beneficial. For those dealing with a progressive or incurable illness, these judgments may occur in the context of values that reflect the dual goal of seeking disease-directed therapies and comfort-directed care.3

Identifying and understanding the patient’s and family’s beliefs and values is an important palliative care skill that helps direct efforts toward improving the quality of end-of-life care. Having open and thoughtful conversations about the patient’s and family’s goals of care can be an effective approach to understanding their values and priorities. These conversations may also help patients and families who are not fully aware of the values they hold deeply and which may guide decisions about their care. In a study examining end-of-life care preferences, parents of seriously ill children identified the following as important end-of-life priorities: honest and complete information, ready access to staff, communication and care coordination, emotional expressions and support by staff, preservation of the integrity of the parent-child relationship, and faith.4 Moreover, when considering withdrawal of artificial life-sustaining support, parents placed the highest priorities on prognosis, quality of life, and their child’s level of comfort.5,6 Honoring these personal values may facilitate the family’s ability to maintain a sense of dignity and integrity.

An important universal value shared by seriously ill patients and their families is the presence of consistent and meaningful relationships within the family unit and with the care team.7 Relationship-based value judgments consistently inform patients’ preferences and decision making.8 Sometimes the expressed values of patients and families differ from those of their healthcare providers. In a study to ascertain parents’ and physicians’ assessments of quality of end-of-life care for children dying from cancer, Mack et al, found that for parents, doctor-patient communication is the principal determinant of high-quality physician care.9 Communicating with honesty and sensitivity about what to expect at the end of their child’s life, communicating directly with the child when appropriate, and preparing the parent for circumstances surrounding the child’s death were all cited by parents as high-quality care. In contrast, physicians’ ratings of high-quality end-of-life care depended on biomedical variables such as less pain and fewer days in the hospital rather than relational parameters. Consequently, clinicians are advised to think about what they consider important in the care of a patient at the end of life and acknowledge the risk of imposing their own value system in the context of a therapeutic alliance with a patient and family facing end-of-life care issues.

Hopes and wishes

In talking with patients and their families about hope, it is important for clinicians to distinguish being hopeful from wishful thinking, having unrealistic expectations, or feeling optimistic.10 Palliative care clinicians can help patients, families, and their healthcare providers by listening without judgment to their experiences and helping to solidify a deeper understanding of these concepts as they evolve in the context of serious illness. Ultimately, hope influences the decisions made by patients and families facing a life-threatening illness.

It is not uncommon to hear staff members worry that parents are not “getting it,” have not been told about the child’s prognosis, or are in denial when the parents make hopeful, optimistic, or wishful statements. A communication schism may occur, and the therapeutic alliance can be severely compromised, if parents are denied the opportunity to express their hopes and wishes. Patients and families may express their hopes and wishes interchangeably, and many use the language of hope in a religious or spiritual context. In the presence of progressive illness, hope can be a powerful coping mechanism, and caregivers must be careful not to strip it away through careless confrontation or premature conversations. It is difficult, however, to differentiate between expressions of wishful thinking and those of hope, and in practice, patients and families often experience a combination of the two. Although helping the patient or family to reframe hope may be appropriate in some circumstances, clinicians must do so only in the context of a relationship based on trust and always remain respectful of the patient’s and family’s overall experiences. A clinician’s responsibility is to acknowledge hope and gently reframe the patient’s and family’s expectations by providing relevant clinical data. In a study to evaluate the relationship between prognostic disclosure and hope, Mack et al. found that parents who received more information about the patient’s prognosis and had high-quality communication were more likely to report communication-related hope, even when the likelihood of a cure was low.11 Such conversations may allow for a balanced perspective of hope for cure and expectations of benefit from treatment.

Sadness and depression

Expressions of hopelessness are often accompanied by profound sadness, defined as an emotional state of varying intensity characterized by feelings of unhappiness.12 Sadness, sorrow, or desolation are normal responses when individuals face a threat to meaningful relationships, a loss of their personal values, or feelings of loneliness and isolation. Sadness in children may be their mourning the loss of the life they previously had (e.g., interacting with friends, playing, attending school) as well as their threatened future; parents mourn the loss of the dreams they held for their child.

Learning to distinguish between sadness and depression is important in palliative care. Depression is a mood disorder characterized by the loss of self-esteem, feelings of guilt, anger, and despair, and negative views about one’s own future. A profound sense of hopelessness at times may be accompanied by suicidal ideation.10 Symptoms of depression include fatigue, insomnia, decreased performance at school or work, loss of appetite, loss of interest in activities previously enjoyed, and social withdrawal. In general, the source of sadness is more specific than that of depression, and a sad person is usually able to experience pleasure and happiness about other aspects of his or her life. For a depressed person, sadness and hopelessness are broader and more pervasive. Although encouraging patients and families to openly share their feelings and reconnect with loved ones may alleviate their sadness, concerns about depression may warrant a psychiatric consult, counseling, and pharmacotherapy.13,14

Fear and anxiety

Fear and anxiety are reactions to the vulnerability and lack of control inherent in the presence of serious illness and to the anticipation of an uncertain future. Although they are normal and expected responses, they may impair parents’ abilities to think clearly and communicate effectively with the clinical team. Fear is an emotional reaction to a specific threat or the expectation of danger. Anxiety is a state of uneasiness and distress in response to a vague and less specific threat and may be manifested as apprehension or worry.12 Anxiety is considered normal when it is in proportion to the source of distress and the person is able to adapt and function once the anxiety has run its course. When anxiety becomes pathological, as in generalized anxiety disorder, phobias, or panic attacks, the degree of anxiety is not proportional to the event that generated the distress, and the person is rendered incapable of functioning effectively (see Chapter 25).

Referrals to a mental health clinician for psychotherapy or evaluation for pharmacotherapy are essential when anxiety compromises a parent’s ability to function. Some people benefit from cognitive behavioral therapy,15 benzodiazepines, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors,16 physical activity,17 hypnosis, or guided imagery.18 Others have used complementary therapies including massage or herbs such as Kava or Valerian.19,20

Assessment of needs

High-quality palliative and end-of-life care requires interdisciplinary patient- and family-centered assessments of physical, emotional, social, and spiritual needs.21,22 Assessment of the effect of the illness on practical aspects of daily life such as eating, sleeping, playing, performing at school or work, housing, transportation, family dynamics, and finances is also important. This assessment can identify what the ill child, adolescent, or parents consider important and provide information on what is needed to optimize comfort and quality of life.23 The family’s values may also reflect a cultural understanding of illness and its treatment.24 The response of the IDT to the patient’s and family’s needs in the presence of progressive illness is considered an ethical imperative.25 Ongoing, regular assessment of these needs allows the team to jointly formulate a care plan with the family that incorporates interventions, practices, and support services that enhance comfort, facilitate care coordination, and optimize quality of life.26 Instruments for assessing pain and other symptoms27 and guidelines for psychosocial assessment and support are available elsewhere.28,29

Providing Anticipatory Guidance

Advanced illness care planning

Care of children with life-threatening conditions is characterized by difficult communication and sensitive information sharing. Establishing a prognosis is part of the therapeutic alliance; patients and families have the right to be informed about the prognosis, and these conversations must occur within the context of a comprehensive, individualized, patient-centered approach.30 Children suffer from the disease and the symptoms that it produces, as well as from the pain and discomfort that result from the procedures and therapies. To empower families to effectively participate in treatment decisions, clinicians must have open and honest conversations about the patient’s prognosis to guide the family’s expectations and identify realistic goal-directed treatment options.21,31,32 Having these conversations and setting realistic goals of care in the context of planning for advanced illness care is an important and effective way to ensure that all of the family’s decisions are made with their child’s well-being and best interests in mind.25 Families can be taught to recognize specific events in the child’s care as markers for the need to revisit his or her prognosis and goals.33 The integration of palliation into the continuum of care may help the family to optimize the child’s comfort and quality of life.26

In general, clinicians recognize that the participation of patients and families in the decision-making process has many benefits, and they are willing to engage in conversations about advanced illness care planning. This is best done as a longitudinal process that is initiated soon after the diagnosis and maintained throughout the illness.34,35 Anticipatory guidance when a child is not in crisis may be better tolerated. For instance, the family may be more receptive to discussing resuscitation recommendations before the child is facing imminent death. An unspoken, but common, fear of parents is that the search and hope for curative therapies will be abandoned or that their child’s care will be compromised. Families will need to know in advance that the team is willing to talk about difficult issues, including the topics of death and dying.36 The team should offer parents the opportunity to think and talk about their worst fear—the possibility that their child may not survive the illness.

Clinicians must recognize that communication, care planning, and establishing realistic care goals are important components of high-quality medical care.37 Clinicians may help parents achieve peace of mind in the presence of a life-threatening illness by providing appropriate medical information.38 Factors perceived by parents to facilitate communication and decision making include trust, confidence, building relationships, demonstrating effort, availability of the team and feeling supported by it, the exchange of information on the health and disease status of the child, an appropriate level of child and parent involvement, and the knowledge that all curative options have been attempted.39,40 Consideration of these factors is particularly important at the end of life when patients and families face the challenges of deciding whether to participate in Phase I clinical studies, maintain or withdraw artificial life support, receive further disease-directed therapy, or agree to a Do Not Resuscitate order, which are some of the most difficult decisions parents have to make.41

Anticipatory guidance for patients with a progressive illness and their families includes helping parents recognize that a cure is no longer possible and helping them to deal with the child’s impending death.42 Physicians usually recognize that a child does not have a realistic possibility of a cure months before the child’s parents do, and earlier recognition of this prognosis by physicians and parents is associated with a stronger emphasis on treatment directed at lessening suffering and greater integration of palliative care.43 Parents also learn the importance of reaching a consensus as a family about critical decisions. Interestingly, the mother’s and father’s goals are often in agreement with each other at the time of diagnosis but can differ at the end of life, and their level of parental agreement about lessening suffering at the end of life may influence their decisions and perceptions about the child’s suffering.44

Finally, parents often worry about making the best decision for their child. Families must be supported during this process to help avoid decisional regret during their bereavement. In a recent study, many bereaved parents indicated that they would not recommend the last course of chemotherapy for children with incurable cancer, mostly because they felt their own children suffered as a result of such therapy.45 Clinicians should aim to understand parents’ perceptions about their own roles in the care of their seriously ill child and assist them in their goal of being the best parents they can be. Parents may blame themselves for the child’s illness or suffering. They may feel guilty because they cannot alleviate suffering. They may also think that they have failed as parents, because they could not protect their child or save him or her from the illness. It is essential that the team reassure parents of their strengths, reframe their perceived deficiencies, and support their decisions.

Ethical and legal considerations

Sometimes families need additional information about ethical and legal considerations (also see Chapter 13). Issues that may be appropriate for anticipatory guidance include the legal aspects of Do Not Resuscitate orders, advanced directives, appointment of a healthcare agent or designation of surrogates, and possible responses of emergency medical professionals if 911 is called. Parents of teenaged children may welcome further education on the need to balance the legal presumption of incompetence of children younger than 18 years with the moral right of a mature adolescent to participate in making decisions about his or her own medical care.46 Some parents may need counsel on the legality of withholding or withdrawing artificial life-sustaining therapies during the last stages of illness because they fear being accused of medical neglect of their child.47,48 Others may need information on legal considerations related to foregoing treatment for religious reasons.49

The use of life-sustaining or invasive interventions may cause harm in patients who are in a persistent vegetative state or in those whose death is imminent. Families can benefit from guidance about what constitutes futility. Physicians and institutions need to have in place a process that aims to enhance deliberation and resolution of conflict when families request therapies considered medically inappropriate.50 Regardless of the clinical scenario, families need to be assured that all treatment options have been explored. In addition, they may benefit from assistance in arranging a second opinion. In situations of conflict, anticipatory guidance may also include helping parents access the institutional Ethics Committee to assist them and their care team in the process of making difficult decisions.51

Symptom control

Families often worry that their child will suffer as the disease progresses or suffer at the end of life.52,53 Informing families about what they may face in caring for their child is helpful. Families need to know the nature of the child’s underlying condition and the symptoms that can be expected.54 For example, severe pain occurs more commonly in children with solid tumors, and neurological symptoms are more common in children with brain tumors or other disorders of the central nervous system. The integration of palliative care adds healthcare resources designed to optimize physical comfort. Families need to know that integrating such services during the early stages of the illness does not represent premature access to end-of-life care.55 Families can be alerted about the possibility of thoughtful and creative pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic management of symptoms such as pain, seizures, anxiety, gastrointestinal distress, insomnia, and dyspnea across the spectrum of the child’s illness. Furthermore, families may need additional counseling on the uses of alternative and complementary therapies such as massage, meditation, Reiki, healing touch, or music thanatology.56 Finally, families should receive information to dissipate fears about the use of opioids and their association with respiratory depression and addiction and understand the differences between physical dependence, tolerance, addiction, and pseudo-addiction.57

Emotional, social, and spiritual care

Chronic, life-threatening, and incurable illness in a child is emotionally challenging and tragic. Anticipatory guidance in psychosocial and spiritual care includes helping families know that they are not alone in these experiences and that there are many resources and strategies for coping and gaining some sense of control.58 Acknowledging the risk for physical and emotional fatigue, recognizing the benefit of communicating their needs to clinicians, and having access to consistent care and support in solving problems may decrease a family’s sense of isolation and despair. The team should provide options to enhance coping such as referrals for grief counseling and financial advice, Web-based support groups and resources, the opportunity to speak to other families who have had a similar experience, and access to relevant books and reading materials. The team should also facilitate access to hospital and/or community supports such as chaplains, art and music therapists, child life specialists, psychologists, psychiatrists, and social workers.

Anticipatory guidance should also include education about community resources.59 This may be even more relevant upon the child’s discharge from the hospital. Parents often experience fear about not having access to the services they perceive as necessary to satisfy the home-based needs of their seriously ill child. Knowing that resources and additional support are available if needed is comforting and stress-relieving.7 Particularly important in this regard is guidance on the use of hospice services for children. Many families have incorrect perceptions about what hospice is and the kind of services that these agencies provide. Presenting hospice as a possible resource at least 12 months prior to expected death has been suggested as a preferred practice for quality care.22 Families also need guidance in accessing hospital, community, local, state, and federal resources.58 Anticipating current and future needs and providing hands-on assistance in accessing these resources is necessary to maximize family function and minimize additional stress. Such needs may include supplemental health insurance, respite care, transportation, financial resources, school and community programs, and home and vehicle modifications.

Care coordination and continuity

Families encounter a multitude of clinicians and may be given different opinions or recommendations, and those clinicians may not know of the child’s and family’s goals.39 In these situations, families must ask clinicians for greater transparency and continuity of information among the members of the team and their medical home.60,61 Families who receive services from healthcare professionals representing a variety of specialties and disciplines may ask for greater care coordination and collaboration in the form of an interdisciplinary care team meeting, or request to meet with healthcare providers as a group, as in a family care conference. Bringing together clinicians to build a consensus based on the shared knowledge of the family’s perspectives allows for consistent communication and works toward mutual goals. Identifying a case manager or advanced practice nurse as the point person to assist the parents may help alleviate stress and confusion.62,63

Provision of continuity of care, including trusting relationships and information, throughout the illness and across the hospital, clinic, and home settings may best convey the principles of nonabandonment.64 Indeed, for patients with chronic conditions, care continuity may be associated with fewer care-related problems.65 This concept presupposes that the therapeutic relationship established among patients, families, and their clinicians will be maintained throughout the illness, particularly when the illness progresses. Barriers imposed by a fragmented healthcare delivery system may threaten this therapeutic bond. Parents need to know that their child’s team will not abandon the patient or family as their goals of care place greater emphasis on comfort and quality of life than on provision of curative therapies. As the illness progresses and more home-based resources are used, families often seek to maintain the close bonds established with clinicians in tertiary care centers, where the child received most of his or her care. Families should know of their right to access a flexible care-coordination approach rooted in ongoing communication, trust, and continuity of care that incorporates understanding of the family’s values, goals, and their religious, cultural, and spiritual beliefs.

Care of the imminently dying child

Anticipatory guidance at the end of life includes helping parents recognize that their child has an incurable illness and when their child is showing signs and symptoms of imminent death.22 Having delicate discussions about what parents hope and expect for their child may help guide care planning for end of life and facilitate the availability of services to enhance comfort and quality of life.43 Conversations about imminent death may also allow clinicians to ensure adequate pain relief and provide the guidance that families need to attend suffering, and allow the family enough time to grieve.66 Anticipatory guidance during this time includes the participation of the child and family in the decision making, identification of symptoms that cause the most distress, strategies for managing escalating symptoms, enhanced focus on comfort and quality of life, access to interdisciplinary psychosocial and spiritual support, and minimizing medical technology or artificial means of prolonging life.22 Furthermore, raising questions about funeral arrangements and the possibility of autopsy or tissue donation can be helpful, because it lets parents know that these difficult topics can be discussed openly before death.

Identifying and addressing the patient’s symptoms that cause the most concern at the end of life is particularly important. This may include parental concerns about pain, weakness, and fatigue and changes in behavior, appearance, or breathing. Parents also report additional benefit from spending time with clinicians, receiving advice about these issues, and having access to appropriate symptom management.67 Depending on the location and needs of the child, home-based services may be provided by a visiting nurse association or hospice agency. If the child transitions home, it is important to consider what measures are practical and possible in the hospital vs. the home setting, where parents may feel a lack of immediate access to healthcare professionals and treatment. Prescription of medications that are potentially useful in the home setting and guidance about how to use those drugs in the event of distressful symptoms empowers parents and offers them a practical and immediate response to their child’s distress at home.

Parents often are conflicted about whether to discuss the likely possibility of death with their child. In a study of bereaved parents whose child had died of cancer, none of the parents who talked to their child about death regretted it, but as many as 27 percent of parents who did not talk to their child about death regretted not having done so, particularly when they sensed that the child was aware of his or her imminent death.68 Parents also struggle with how to talk to their healthy children about their ill sibling’s imminent death. Parents may benefit from counseling on the cognitive and developmental understanding of the concepts of illness and death.69 Conversations in advance that allow parents to formulate or even role play can help alleviate parental distress. Encouraging parents to verbalize and incorporate their family’s communication style and beliefs about death and afterlife into the conversation can lead to authentic and effective communication with their children. Guidelines to help parents and clinicians communicate with children about death have been suggested by Beale et al.70 Members of the IDT may have additional experience and resources to counsel parents through this difficult process.

Finally, anticipatory guidance about the patient’s and family’s preferences for the location of death may represent a better marker of quality palliative care than the actual location of death.71 Planning where the child will die correlates with an increased number of children dying at home, fewer children dying in the critical care unit or undergoing endotracheal intubation, and less parental regret about the location of death.

Bereavement Care

The death of a child is one of the most devastating events in the life of a parent, and for a child, the death of a sibling may be equally traumatic. Counseling on the need for self care during the bereavement process is of utmost importance. Bereaved parents, for example, experience high rates of anxiety, depression,72 and psychiatric hospitalizations.73 The death of a child is also associated with an overall increased mortality among bereaved parents.74 Factors that complicate the bereavement process include whether the parents perceived the child to be in pain or that the child experienced a difficult time at the moment of death.75 Access to psychosocial support and guidance prior to or at the time of death may ease bereavement.76 Families may benefit from knowing that bereavement is highly individual with no timetable and that there is no right or wrong answer on how one should grieve.

Bereaved parents should be counseled on the possibility of experiencing feelings of disbelief, yearning, anger, and sadness.77 These feelings are normal, and parents may struggle with them for years after the death of their child.76 Parents may also benefit from sharing their burden with others, particularly supportive family members.78 Some bereaved family members need guidance about the struggle to resume living, continue working, caring for siblings, and/or relating within the couple. Being aware of prior stressors and how these may further complicate an individual’s bereavement experience may help guide appropriate clinical interventions. Counseling may also include information about ways for families to navigate their grief, such as normalizing their desire to stay connected to the child after his or her death and maintaining the child’s legacy. During the bereavement process, parents should be informed of the availability of specialized counseling if the intensity of their grief interferes with their ability to function normally.

1 Hinds P.S., Oakes L., Furman W., et al. Decision making by parents and healthcare professionals when considering continued care for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24(9):1523-1528.

2 Robinson M.R., Thiel M.M., Backus M.M., Meyer E.C. Matters of spirituality at the end of life in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e719-e729.

3 Bluebond-Langner M., Belasco J.B., Goldman A., Belasco C. Understanding parents’ approaches to care and treatment of children with cancer when standard therapy has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(17):2414-2419.

4 Meyer E.C., Ritholz M.D., Burns J.P., Truog R.D. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117(3):649-657.

5 Meyer E.C., Burns J.P., Griffith J.L., Truog R.D. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(1):226-231.

6 Michelson K.N., Koogler T., Sullivan C., Ortega M.P., Hall E., Frader J. Parental views on withdrawing life-sustaining therapies in critically ill children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(11):986-992.

7 Kane J.R., Hellsten M.B., Coldsmith A. Human suffering: the need for relationship-based research in pediatric end-of-life care. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2004;21(3):180-185.

8 Hinds P.S., Drew D., Oakes L.L., et al. End-of-life care preferences of pediatric patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9146-9154.

9 Mack J.W., Hilden J.M., Watterson J., et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155-9161.

10 Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling. Nashville, Tenn: Abingdon Press, 2009.

11 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Cook E.F., Grier H.E., Cleary P.D., Weeks J.C. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(35):5636-5642.

12 The American Heritage Dictionary. Second College Edition. 2009. Houghton Mifflin: Boston, Mass.

13 Burns B.J., Hoagwood K., Mrazek P.J. Effective treatment for mental disorders in children and adolescents. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 1999;2(4):199-254.

14 Campbell M., Cueva J.E. Psychopharmacology in child and adolescent psychiatry: a review of the past seven years. Part II. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34(10):1262-1272.

15 Cartwright-Hatton S., Roberts C., Chitsabesan P., Fothergill C., Harrington R. Systematic review of the efficacy of cognitive behaviour therapies for childhood and adolescent anxiety disorders. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(Pt 4):421-436.

16 Seedat S., Stein M.B. Double-blind, placebo-controlled assessment of combined clonazepam with paroxetine compared with paroxetine monotherapy for generalized social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(2):244-248.

17 Parfitt G., Eston R.G. The relationship between children’s habitual activity level and psychological well-being. Acta Paediatr. 2005;94(12):1791-1797.

18 Huynh M.E., Vandvik I.H., Diseth T.H. Hypnotherapy in child psychiatry: the state of the art. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13(3):377-393.

19 Burden B., Herron-Marx S., Clifford C. The increasing use of reiki as a complementary therapy in specialist palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2005;11(5):248-253.

20 Beaubrun G., Gray G.E. A review of herbal medicines for psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(9):1130-1134.

21 Kane J.R., Primomo M. Alleviating the suffering of seriously ill children. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2001;18(3):161-169.

22 A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality. National Quality Forum. 2006. Available at www.qualityforum.org

23 Freyer D.R., Kuperberg A., Sterken D.J., Pastyrnak S.L., Hudson D., Richards T. Multidisciplinary care of the dying adolescent. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;15(3):693-715.

24 De T.M., Kovalcik R. The child with cancer. Influence of culture on truth-telling and patient care. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;809:197-210.

25 Wolfe J. Suffering in children at the end of life: recognizing an ethical duty to palliate. J Clin Ethics. 2000;11(2):157-163.

26 Baker J.N., Hinds P.S., Spunt S.L., et al. Integration of palliative care practices into the ongoing care of children with cancer: individualized care planning and coordination. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2008;55(1):223-250. xii

27 Collins J.J., Devine T.D., Dick G.S., et al. The measurement of symptoms in young children with cancer: the validation of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale in children aged 7–12. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(1):10-16.

28 Kazak A.E., Rourke M.T., Alderfer M.A., Pai A., Reilly A.F., Meadows A.T. Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: a blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(9):1099-1110.

29 Kazak A.E., Cant M.C., Jensen M.M., et al. Identifying psychosocial risk indicative of subsequent resource use in families of newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(17):3220-3225.

30 Maltoni M., Caraceni A., Brunelli C., et al. Prognostic factors in advanced cancer patients: evidence-based clinical recommendations—a study by the Steering Committee of the European Association for Palliative Care. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):6240-6248.

31 Baker J.N., Barfield R., Hinds P.S., Kane J.RA. Process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: the Individualized Care Planning and Coordination Model. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007;13(3):245-254.

32 Kane J.R., Himelstein B.P. Palliative care for children. In Berger A.M., Shuster J.L., Von Roenn J.H., editors: Principles and practice of palliative medicine and supportive oncology, ed 3, Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

33 Walling A., Lorenz K.A., Dy S.M., et al. Evidence-based recommendations for information and care planning in cancer care. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(23):3896-3902.

34 Mack J.W., Wolfe J. Early integration of pediatric palliative care: for some children, palliative care starts at diagnosis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2006;18(1):10-14.

35 Wharton R.H., Levine K.R., Buka S., Emanuel L. Advance care planning for children with special health care needs: a survey of parental attitudes. Pediatrics. 1996;97(5):682-687.

36 Levetown M. Communicating with children and families: from everyday interactions to skill in conveying distressing information. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1441-e1460.

37 Hui D., Con A., Christie G., Hawley P.H. Goals of care and end-of-life decision making for hospitalized patients at a Canadian tertiary care cancer center. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(6):871-881.

38 Mack J.W., Wolfe J., Cook E.F., Grier H.E., Cleary P.D., Weeks J.C. Peace of mind and sense of purpose as core existential issues among parents of children with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(6):519-524.

39 Hsiao J.L., Evan E.E., Zeltzer L.K. Parent and child perspectives on physician communication in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5(4):355-365.

40 Hinds P.S., Oakes L., Furman W., et al. End-of-life decision making by adolescents, parents, and healthcare providers in pediatric oncology: research to evidence-based practice guidelines. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(2):122-134.

41 Hinds P.S., Oakes L., Furman W., et al. Decision making by parents and healthcare professionals when considering continued care for pediatric patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1997;24(9):1523-1528.

42 Kars M.C., Grypdonck M.H., de Korte-Verhoef M.C., et al. Parental experience at the end-of-life in children with cancer: ‘preservation’ and ‘letting go’ in relation to loss. Support Care Cancer. 2009.

43 Wolfe J., Klar N., Grier H.E., et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2469-2475.

44 Edwards K.E., Neville B.A., Cook E.F.Jr, Aldridge S.H., Dussel V., Wolfe J. Understanding of prognosis and goals of care among couples whose child died of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(8):1310-1315.

45 Mack J.W., Joffe S., Hilden J.M., et al. Parents’ views of cancer-directed therapy for children with no realistic chance for cure. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(29):4759-4764.

46 Committee on Bioethics, American Academy of Pediatrics. Informed consent, parental permission, and assent in pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 1995;95(2):314-317.

47 Ridgway D. Court-mediated disputes between physicians and families over the medical care of children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158(9):891-896.

48 American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Guidelines on foregoing life-sustaining medical treatment. Pediatrics. 1994;93(3):532-536.

49 Mercurio M.R., Adam M.B., Forman E.N., Ladd R.E., Ross L.F., Silber T.J. American Academy of Pediatrics policy statements on bioethics: summaries and commentaries: part 1. Pediatr Rev. 2008;29(1):e1-e8.

50 Medical futility in end-of-life care: report of the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. JAMA. 1999;281(10):937-941.

51 Committee on Bioethics. Institutional ethics committees. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):205-209.

52 Wolfe J., Grier H.E., Klar N., et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(5):326-333.

53 Collins J.J., Byrnes M.E., Dunkel I.J., et al. The measurement of symptoms in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2000;19(5):363-377.

54 Goldman A., Hewitt M., Collins G.S., Childs M., Hain R. Symptoms in children/young people with progressive malignant disease: United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group/Paediatric Oncology Nurses Forum survey. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):e1179-e1186.

55 Duncan J., Spengler E., Wolfe J. Providing pediatric palliative care: PACT in action. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2007;32(5):279-287.

56 Horowitz S. Complementary therapies for end-of-life care. Alternative Complementary Therapies. 2009;15(5):226-230.

57 Levetown M., Frager G. UNIPAC Eight: The hospice/palliative medicine approach to caring for pediatric patients. Glenview, Ill: American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 2003.

58 Jones B.L. Pediatric palliative and end-of-life care: the role of social work in pediatric oncology. J Soc Work End Life Palliat Care. 2005;1(4):35-61.

59 Ziring P.R., Brazdziunas D., Cooley W.C., American Academy of Pediatrics, et al. Committee on Children with Disabilities. Care coordination: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1999;104(4 Pt 1):978-981.

60 Care coordination in the medical home: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1238-1244.

61 Stille C.J., Antonelli R.C. Coordination of care for children with special health care needs. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2004;16(6):700-705.

62 Antonelli R.C., Stille C.J., Antonelli D.M. Care coordination for children and youth with special health care needs: a descriptive, multisite study of activities, personnel costs, and outcomes. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1):e209-e216.

63 Meier D.E., Beresford L. Advanced practice nurses in palliative care: a pivotal role and perspective. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(3):624-627.

64 Christakis D.A., Wright J.A., Zimmerman F.J., Bassett A.L., Connell F.A. Continuity of care is associated with well-coordinated care. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(2):82-86.

65 Mack J.W., Co J.P., Goldmann D.A., Weeks J.C., Cleary P.D. Quality of health care for children: role of health and chronic illness in inpatient care experiences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(9):828-834.

66 Shinjo T., Morita T., Hirai K., et al. Care for imminently dying cancer patients: family members’ experiences and recommendations. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(1):142-148.

67 Pritchard M., Burghen E., Srivastava D.K., et al. Cancer-related symptoms most concerning to parents during the last week and last day of their child’s life. Pediatrics. 2008;121(5):e1301-e1309.

68 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., Henter J.I., Steineck G. Talking about death with children who have severe malignant disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(12):1175-1186.

69 Schum L.N., Kane J.R. Psychological adaptation of the dying child. In: Walsh D., editor. Palliative medicine. Saunders, Elsevier; 2009:1085-1093.

70 Beale E.A., Baile W.F., Aaron J. Silence is not golden: communicating with children dying from cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(15):3629-3631.

71 Dussel V., Kreicbergs U., Hilden J.M., et al. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;37(1):33-43.

72 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., Henter J.I., Steineck G. Anxiety and depression in parents 4–9 years after the loss of a child owing to a malignancy: a population-based follow-up. Psychol Med. 2004;34(8):1431-1441.

73 Li J., Laursen T.M., Precht D.H., Olsen J., Mortensen P.B. Hospitalization for mental illness among parents after the death of a child. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(12):1190-1196.

74 Li J., Precht D.H., Mortensen P.B., Olsen J. Mortality in parents after death of a child in Denmark: a nationwide follow-up study. Lancet. 2003;361(9355):363-367.

75 Kreicbergs U., Valdimarsdottir U., Onelov E., Bjork O., Steineck G., Henter J.I. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9162-9171.

76 Kreicbergs U.C., Lannen P., Onelov E., Wolfe J. Parental grief after losing a child to cancer: impact of professional and social support on long-term outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(22):3307-3312.

77 Maciejewski P.K., Zhang B., Block S.D., Prigerson H.G. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA. 2007;297(7):716-723.

78 Laakso H., Paunonen-Ilmonen M. Mothers’ experience of social support following the death of a child. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11(2):176-185.