Chapter 28

Understanding Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The natural healing force within each of us is the greatest force in getting well.

Hippocrates (460–377 BCE)

General Considerations

Studies have shown that the frequency of use of complementary or alternative medical therapy in the United States is far greater than previously reported. These therapies include relaxation techniques, imagery, chiropractic, massage, spiritual healing, herbal medicine, acupuncture, homeopathy, folk remedies, and prayer, to name a few. It has been estimated that 42% of the American population uses at least one of these and other alternative healing methods to satisfy their medical needs. The most common users of complementary and alternative therapy are more affluent people, women, those better educated, individuals born after 1950, and those who are concerned about emotional stress and the environment. The most common therapies were relaxation techniques (18%), massage (12%), herbal medicine (10%), and megavitamin therapy (9%). The perceived efficacy of these therapies ranged from 76% (hypnosis) to 98% (energy healing). The number of visits to providers of this health care is greater than the number of visits to all primary care medical doctors nationwide. More than 70% of these patients never mention using alternative therapy to their clinicians. Out-of-pocket expenditures of more than $34 billion per year in the United States are a testament to a widely held belief that complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) therapies have benefits that outweigh their costs. This figure is in contrast to the $12.8 billion spent out of pocket annually for all hospitalizations in the United States.

One of the reasons patients seek complementary and alternative therapies may be a failure in the doctor-patient relationship. Health care providers often fail to discuss the use of these therapies because they lack adequate knowledge in this area and have poor insight into the cultures and beliefs of those who practice CAM. To many health care providers, “alternative medicine” entails the threat of displacing conventional medicine for the sake of unproven therapies. It may lack organization and the rigorous, scientific standards of Western, evidence-based medicine. The response of the health care providers ranges from outright dismissal of the practices to a gradual recognition that their extensive use can no longer be ignored. A lack of communication and knowledge in this area may also prove to be detrimental to the patient because the use of some forms of these therapies, if unsupervised, may be dangerous.

There has been an increasing interest throughout the world in the use of natural ingredients for health, especially tea. Tea is the world’s second most popular beverage after water. Green tea accounts for approximately 20% of all tea consumed. It has been claimed that overall health of the body, especially the oral cavity, can be maintained by the consumption of green tea. Green tea is not fermented; therefore, it contains polyphenols that are inactivated in the fermentation process of black tea production. Green tea has been consumed in East Asia, where its benefits have been claimed for centuries. Green tea polyphenols possess antioxidant and antiviral properties that account for its benefits; these benefits have been touted to include lowering blood pressure, lowering cholesterol, stabilizing blood glucose, inhibiting bacterial growth, and blocking many carcinogenic agents. Polyphenols have been shown to inhibit the growth of Streptococcus mutans, the major etiologic bacterium associated with dental caries, and Porphyromonas gingivalis, the bacterium associated with periodontal disease.

In April 1995, the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) defined CAM as “a broad domain of healing resources that encompasses all health systems, modalities, and practices and their accompanying theories and beliefs, other than those intrinsic to the politically dominant health system of a particular society or culture in a given historical period.” This group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products is not currently part of conventional (i.e., allopathic) medicine, although some conventional medical practitioners (those with an MD, DO, or other health-related degrees) are also practitioners of CAM. The CAM marketplace is currently valued at $24 billion or more, and the growth rate is close to 15% per year. Since the inception of the NCCAM, Congress has provided almost $550 million to promote CAM and CAM research. In fiscal year 2004, the funding for NCCAM was $117.7 million.

In December 1995, the American Medical Association (AMA) passed the resolution “Unconventional Medical Care in the United States.” The AMA encourages NCCAM to determine by objective scientific evaluation the efficacy and safety of practices and procedures of unconventional medicine and encourages its members to become better informed regarding the practices and techniques of alternative or unconventional medicine.1

What is CAM? Complementary medicine, such as aromatherapy, is used in conjunction with conventional medicine, for example, to lessen a patient’s postoperative discomfort. Alternative medicine, such as some herbal medicines, is used instead of conventional medicine to treat cancer. Alternative therapies include, but are not limited to, the following disciplines: folk medicine, herbal medicine, diet fads, homeopathy, faith healing, new age healing, chiropractic, acupuncture, naturopathy, reflexology, massage, and music therapy. Integrative medicine combines conventional medical and CAM therapies for which there is some scientific evidence of safety and effectiveness, regardless of their origin.

The purpose of this chapter is to educate the reader about CAM. Medical schools in the United States are now including courses in which CAM is taught, but 80% of medical students polled have indicated that they would like more information. Because 29 health care insurance companies in the United States now cover CAM therapies and 67% of health maintenance organizations now offer at least one form of CAM, it is crucial for health care providers to become more cognizant about these therapies. In the future, there will be more well-designed, randomized, controlled studies that will provide answers to many of today’s questions regarding CAM.

Classifications of Complementary and Alternative Medicine

The NCCAM has classified CAM therapies into five major but overlapping categories:

1. Alternative medical systems

3. Biologically based therapies

Mind-body interventions entail a wide variety of techniques to improve the mind’s capacity to affect bodily function and symptoms. Cognitive therapies, biofeedback, meditation, hypnosis, prayer, and creative outlets such as dance, music, and art are common examples of mind-body interventions.

Biologically based therapies involve herbs, vitamins, dietary supplements, and foods to treat disease. Around the world, these products are extraordinarily popular, and billions of dollars are spent on them in the United States alone. The assumption is that natural products are healthier and better than synthetic chemicals for treating disease. Dietary supplements are not considered drugs and therefore are not regulated and do not require U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval.

Manipulative and body-based methods include modalities that move one or more parts of the body. These methods include massage, chiropractic, osteopathy, and reflexology. Chiropractic is concerned with the relationship between structure and function. The primary structure is the spine, and the function is the nervous system; this relationship is thought to affect the restoration and preservation of health. The first chiropractic adjustment was given in 1895. The basic principle of chiropractic is that any interference with the transmission, reception, or application of impulses that travel over the nervous system causes functional abnormalities or disease. This interference may be the result of a vertebral subluxation. Over the years, numerous definitions have been formulated to describe the nature of subluxation. In all of these, there are at least four main criteria or characteristics:

The vertebral subluxation may be the result of any of the following causes: trauma, toxins (infections, poisons), and autosuggestion (psychologic factors). Vertebral subluxation is treated with a chiropractic manipulation referred to as an adjustment. The chiropractic adjustment is a specific form of direct articular manipulation characterized by a dynamic, forceful, high-velocity thrust of controlled amplitude. These adjustments may be administered by hand or instruments directed at specific articulations. It is believed that chiropractic adjustments energize the life force that connects the spine to all parts of the body to promote healing and restore health. Chiropractic has become one of the largest drug-free healing professions. According to a survey released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nearly 20% of the adult population in the United States has used chiropractic at least once.

Osteopathy focuses on diseases arising in the musculoskeletal system. The belief is that all the body’s systems work together, and disturbances in one system affect functions in another. The field involves understanding the entire patient, physically, psychologically, and emotionally, to uncover the underlying causes of symptoms. Osteopathic physicians use musculoskeletal manipulation, recommendations about diet and exercise, and general preventive medicine to alleviate pain, restore function, and promote health.

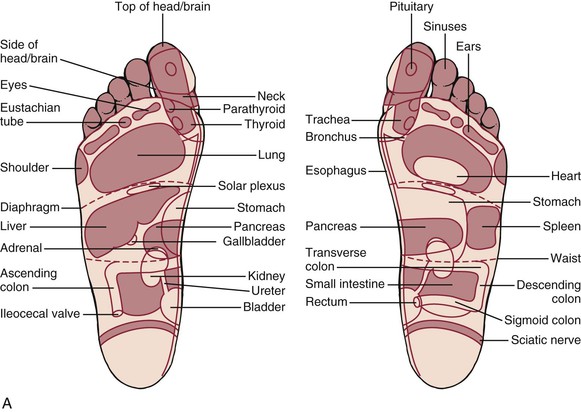

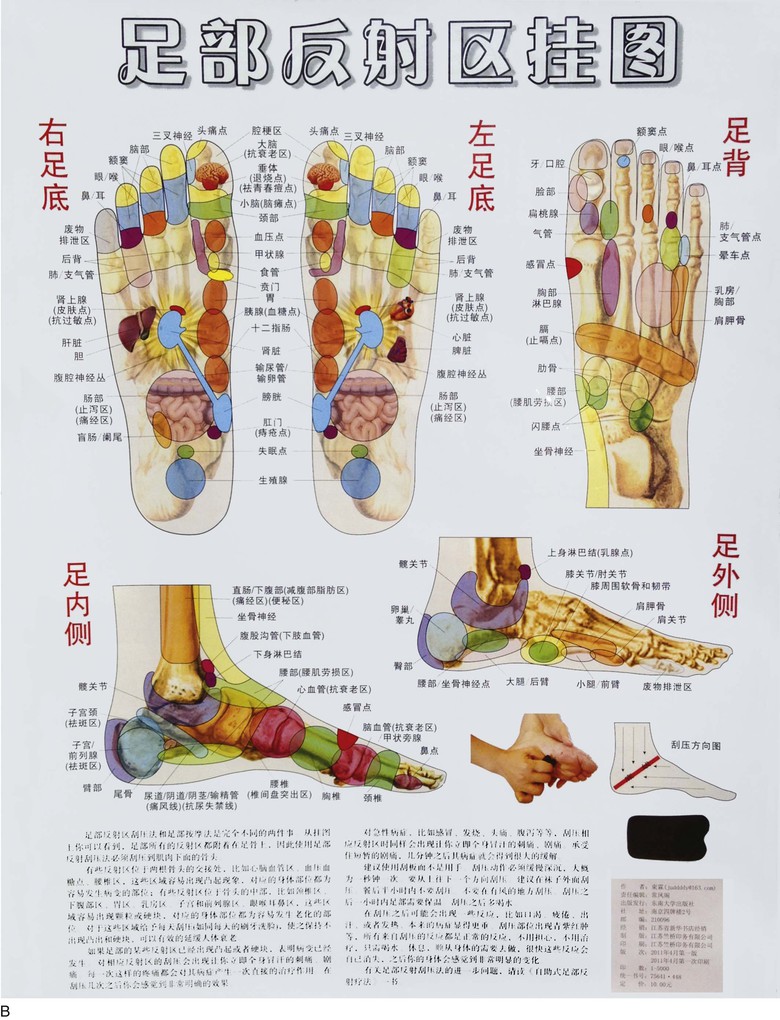

Reflexology is a body-based therapy in which pressure is applied to the feet, hands, ears, and cranium to treat a variety of ailments and promote well-being and improved health. The therapist applies the tips of the fingers, the thumb, the elbow, and the hand firmly to areas of the recipient’s body to assess the state of health and treat every part of the body. Dating back to as early as 2700 BCE, reflexology is believed to link every organ or gland in the body to a reflex point on the foot or hand; these areas are linked through a series of longitudinal and transverse zones that run from the feet or hands through the legs and arms, respectively, to the organ or gland. By manipulating the reflex area, most of which are found on the soles of the feet, as shown in Figure E28-1A, the therapist can treat that area of the body. It is believed that foot reflexology, which is not a simple foot massage, can relieve tension and blockages by stimulating sensory receptors in the nerves of the foot (see Fig. E28-1B). As a result, energy is created that extends to the spinal cord and dispersed throughout the nervous system. Reflexology has been used for many conditions, including, among other things, improving the immune system, paralysis, arthritis, diabetes, and sleep disorders; lowering blood pressure; and stimulating circulation.

Figure E28–1 A, Reflexology foot maps. The densest concentration of reflex areas is found on the soles of the feet. B, As the title in Chinese reads, this is a poster of the reflex areas of the foot. (Artist unknown.)

Energy therapies, which involve the use of energy fields, are categorized into three types: biofield therapies, bioelectromagnetic-based therapies, and acupuncture. The term biofield was coined in 1994 at a meeting at the NIH, and the biofield hypothesis purports that all objects radiate an electromagnetic field. If an object such as part of a healer’s body, a nutritional supplement, or an externally applied electromagnetic field is brought near to or inside the body of an individual, the frequencies radiated by the object or field interact with the individual’s field. Biofields have been described traditionally by the ancient Indians as prana, by the Chinese as qi (or chi), by the Japanese as ki, by Jewish mysticism as “astral light,” and by Christian painters as “halos.” Current practices involving biofield therapies are intended to affect a patient’s energy field for the purpose of healing by having a healer place his or her hands in or through them; the therapist’s healing force restores the patient. Examples of this type of energy therapy include Reiki, qi gong, and therapeutic touch. Reiki, a Japanese word meaning “universal life energy,” is an ancient form of healing by touch and is based on the belief that when spiritual energy is channeled through a Reiki practitioner, the patient’s spirit is healed. It is a way of channeling this energy through one’s hands, enabling the body to accelerate its own healing process. Qi gong is a Chinese technique that combines slow-moving meditative postures, meditation, stretching, and regulation of breathing to enhance the flow of qi in the body to enhance immune function and improve circulation.

Bioelectromagnetic-based therapies involve the unconventional use of electromagnetic fields. Positioning external magnetic fields near or around the person, usually by placing magnets on the body, into clothing, or in mattresses, is an example of this type of therapy.

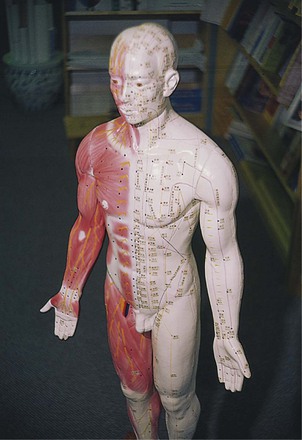

Acupuncture is a healing art in which needles are placed into the body to allow qi (energy) to flow unimpeded. Advances in acupuncture allow for the attachment of electrodes to the needles through which small currents are passed. The dominant form of therapy in traditional Chinese medicine is acupuncture. To understand acupuncture, the reader must first understand the concept of meridians. Meridians are a unique part of Chinese medical theory; they are the channels through which qi flows among the organs, adjusting and harmonizing their activities. The meridians, which are not blood vessels, are 20 to 50 µm in diameter and link together all the fundamental substances and organs. They are bilateral and exist beneath the surface of the skin. The places at which the branches reach the skin surface are designated as acupuncture sites. Each meridian has an entry and exit point; energy enters through the entry point and flows through to the exit point. There are 12 primary meridians of the body, each running vertically, bringing qi and the other four essential substances to specific parts of the body. No part of the body is without qi; a blockage causes an imbalance in the flow of the life force. In Figure E28-2, a male model demonstrates where the meridians and acupuncture sites are indicated. Figure E28-3A depicts the clinician placing an acupuncture needle in the buttocks of a man with sciatica; Figure E28-3B shows all the needles in position.

Figure E28–2 Meridians and acupuncture sites on male model.

Figure E28–3 Acupuncture. A, Physician inserting needles into a patient with sciatica. B, Needles in position.

Shen is the energy, unique to human life, that is responsible for the spirit, consciousness, emotions, and thoughts. It is associated with the force of human personality. Jing is the fluid that is the basis of reproduction and development. Xue (pronounced “schwhey”) moves in the same channels as qi and is similar to blood but is produced by food, refined in the spleen, and transported to the lungs, where nutritive qi turns it into xue. Jin-ye is all fluids other than xue. It includes sweat, urine, saliva, mucus, bile, and gastric juice. These five essential substances constitute the basis for the Chinese traditional medical system.

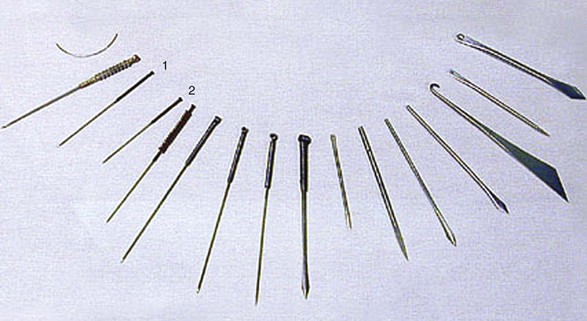

Acupuncture is used for prevention and treatment of disease and for maintenance of health by manipulating the flow of qi and xue, or body fluids, through the body channels. Although most Western clinicians have heard of acupuncture, few understand it. The Chinese have used acupuncture for more than 6000 years to stimulate or awaken the natural power within the body. It is estimated that there are 9 to 12 million treatments a year in the United States. Acupuncture involves the use of nine fine needles, each with a specific purpose. There are as many as 2000 specific points, each 3 mm in diameter, along the meridian lines on the skin into which these needles can be inserted. Most acupuncturists use only 150 of these points. The Chinese have different names for each acupuncture point. Examples of the classic needles, which also include scalpel and lancet-like instruments, are shown in Figure E28-4. The needles marked “1” and “2” are the most commonly used needles. The needles act as antennae to direct qi to organs of the body. At other times, the needles may drain qi when it is excessive.

Figure E28–4 Classic acupuncture needles. 1 and 2, Thin filiform needles most commonly used in the United States.

Acupuncture has been used to treat illnesses from childhood to old age. Figure E28-5 depicts an acupuncture tray with supplies. While lecturing in Taiwan, I had the good fortune to visit the China Medical College in Taichung, where there is a special department for patients who wish to obtain traditional Chinese medical treatment. The child shown in Figure E28-6A was brought in by his mother, who stated that her son was having symptoms of a cold. The man in Figure E28-6B was complaining of sinus problems, and the older woman in Figure E28-6C was complaining of headaches. Figure E28-6D is the foot of the child shown in Figure E28-6A.

Figure E28–5 Acupuncture supplies.

Figure E28–6 Acupuncture. A, Child with upper respiratory infection, under treatment. B, Man with sinus headache, under treatment. C, Woman with headache, under treatment. D, Foot of child with upper respiratory infection shown in A.

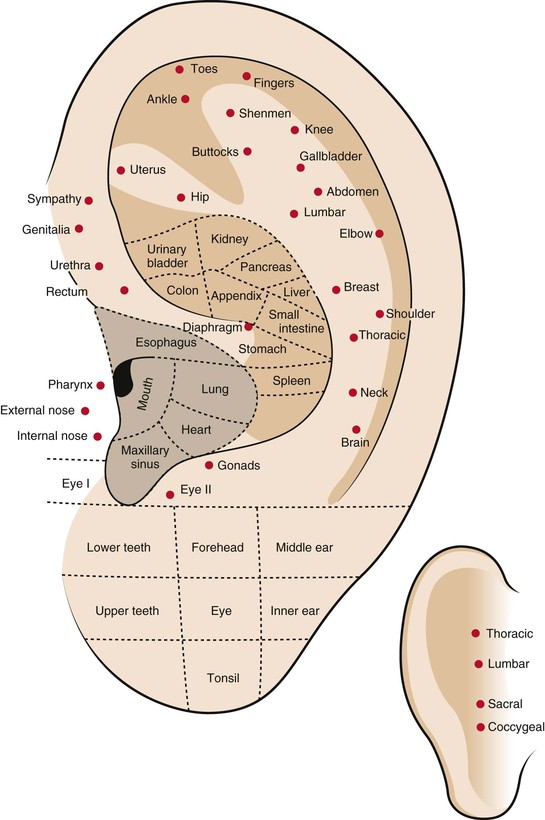

Ear acupuncture, known as auriculotherapy, is practiced by traditional Chinese acupuncturists for the diagnosis and therapy of organ system disharmony. This technique, however, did not develop in China. A French physician, Paul Nogier, introduced this concept in 1958. Figure E28-7 shows the acupuncture sites of the ear. Auriculotherapy is based on the concept that there are specific parts of the ear that can be related to specific parts of the body and its functions. Although the specificity of ear acupuncture points has never been clearly demonstrated, most acupuncturists agree that ear acupuncture has a calming effect. Indeed, the most frequently cited ear point used in treatments is called shenmen, or spirit gate. The Handbook of Chinese Auricular Therapy (Chen and Cui, 1997) states that this point “is used in numerous diseases of the neuropsychiatric system. … The application of this point is fairly extensive and flexible, covering no [fewer] than 30 kinds of diseases or ailments.”

Figure E28–7 Acupuncture sites of the ear.

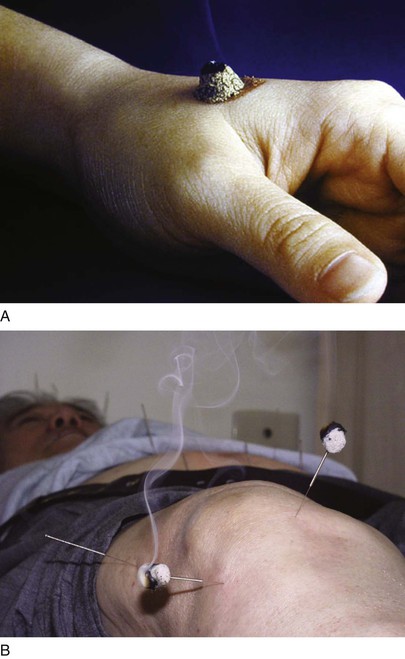

Moxibustion is a specific form of acupuncture in which herbs are burned to stimulate specific acupuncture sites. If a disease fails to respond to traditional acupuncture, moxibustion is used. Moxa leaves (Artemisia chinensis) are either rolled into a cigar-shaped stick or pulverized and made into a cone. The moxa stick is lit, and the glowing end is held over the vital spot to be treated; the cone is placed on the skin over the acupuncture site and ignited, letting it burn slowly near the skin, as shown in Figure E28-8A. Often, the rolled moxa cone is placed on the end of an acupuncture needle and then lit to enhance the acupuncture therapy; this is shown in Figure E28-8B in a patient complaining of lower back pain. Moxibustion is used for conditions in which there is an excess of yin and is contraindicated for heat and excess yang disharmonies.

Figure E28–8 Moxibustion. A, Moxibustion cone. B, Moxibustion and acupuncture therapy in a patient with low back pain.

In 1997, the NIH convened a panel of independent experts to review the clinical studies of acupuncture. The panel noted that the results of several studies, many sponsored by the NIH, were unclear because of design, sample size, and other factors, complicated by difficulties in the use of appropriate control subjects. The panel did agree that acupuncture has been shown to be effective for relief of the following:

The panel determined that acupuncture may be useful as an adjunct treatment, as an acceptable alternative, or as part of a comprehensive management program for addiction, stroke rehabilitation, headache, menstrual cramps, tennis elbow, fibromyalgia, myofascial pain, osteoarthritis, low back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and asthma. Further research is likely to uncover additional areas in which acupuncture interventions are useful.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

There are many traditional medical practices. Of particular note are the Chinese, Ayurvedic, and Greek systems of healing. Owing to the limitations of space in this chapter, one traditional system of healing, Chinese medicine, which has influenced so many other systems, is considered.

With more than 10 million people, the Asian and Pacific Islander group represents the third largest minority group in the United States. The Chinese approach to healing is a rich and complex tradition. It emphasizes the importance of promoting balance and harmony in body, mind, and spirit, and has become the foundation for many other traditional medical systems. Chinese medicine had its origins more than 2500 years ago and is still in use to treat millions of people in China and throughout the world. As a result, to the traditional Chinese healers, allopathic medicine is new and experimental.

Chinese medicine is based on the idea that the human system is a microcosmic mirror of the macrocosmic universe. This means that no one thing can exist without the existence of the others. Each person is subject to the same laws that govern the stars, the planets, the trees, and the land. Tao, sometimes translated as “the infinite origin,” is the single unified source from which all life and the entire universe originated; it is the way to ultimate reality. To follow the laws of nature is to be blessed with good health, long life, and good fortune. Because nature is the most enduring manifestation of tao, much of the traditional terminology of Chinese medicine is derived from natural phenomena, such as fire and water, wind and heat, and dryness and dampness. When the elements in the human body remain in balance, “fair weather” is said to prevail in the body, and the human is well both physically and mentally.

Tao created two opposing forces, yin and yang, which are the opposites that combine to create everything in the world. Yin is a force of darkness and is associated with such qualities as femininity, cold, rest, passivity, emptiness, introverted, and negative energy. Yang is a force of brightness and is associated with masculinity, heat, stimulation, activity, excitement, vigor, fullness, extroverted, and positive energy. Table 28-1 lists the aspects of yin and yang polarity.

Table 28–1

Aspects of Yin and Yang Polarity

| Aspect | Yin | Yang |

| Cosmic bodies | Earth Moon |

Sun |

| Energy condition | Passive | Aggressive |

| Mentally active | Physically active | |

| Asleep | Awake | |

| Weak | Strong | |

| Empty | Full | |

| Deficient | Excessive | |

| Cold | Hot | |

| Time of day | Night | Day |

| Season | Fall | Spring |

| Winter | Summer | |

| Magnetic pole | Negative | Hot |

| Speed | Slow | Fast |

| Body location | Interior | |

| Lower torso | Upper torso | |

| Lower extremities | Upper extremities | |

| Feet | Head | |

| Right side | Left side | |

| Back | Front | |

| Exterior | ||

| Gender | Female | Male |

| Numbers | Even | Odd |

| Distance | Near | Far |

| Relative moisture | Very moist, saturated | Dry |

| Quality of light | Dark | Light |

| Acid/base | Alkaline | Acid |

| Speed | Slow | Fast |

| Metabolism | Anabolism | Catabolism |

| Psychic type | Contemplative | Active |

| Introverted | Extroverted | |

| Gentle | Robust |

There are two main concepts in traditional Chinese medicine. The first is that the occurrence of disease represents a failure in preventive health care. The second is that health is a responsibility shared equally by the patient and clinician. According to a Chinese proverb, “The superior physician teaches his patients how to stay healthy.” In traditional Chinese medicine, the clinician treats the patient as a whole system rather than dealing with separate parts, as is common in Western medicine. An important belief is that the mind is engaged to control and guide energy to heal and repair the body. Chinese medicine is a system of preserving health and curing disease that treats the mind, body, and spirit as a whole.

Whereas the Western clinician starts with a symptom and tries to search for the cause of a specific disease, the traditional Chinese clinician directs his or her attention to the whole patient and forms a “pattern of disharmony.” This pattern describes the situation of “imbalance” in the patient’s body. The traditional Chinese clinician asks not “Which A is causing B?” but “What is the relationship between A and B?” The patterns of disharmony provide the framework for therapy. In Chinese medicine, a person does not catch the flu; a person develops a disharmony. If a patient requires an antibiotic, herbs or acupuncture may be used to dispel the disharmony. Regardless of the ailment, the mind, body, and spirit must be treated as a whole. Healing is achieved by rebalancing yin and yang and restoring harmony in the whole person.

The traditional Chinese clinician inspects a patient in four stages: looking, listening or smelling, asking, and touching. Inspection of the tongue and palpation of the pulse are the two most important examinations. The tongue is believed to be the clearest indicator of the nature of the disharmony. The Chinese recognize more than 100 different conditions of internal energy imbalance, based on the color and texture of the tongue “fur.” The condition of the five major organ-energy systems is evaluated according to their corresponding areas on the tongue. These systems are the kidneys, liver, spleen, lungs, and heart.

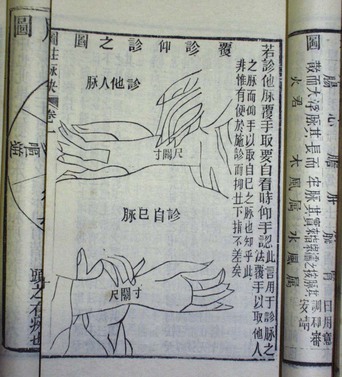

In traditional Chinese medicine, pulse diagnosis is evaluated at the radial artery. It is believed that disharmonies of the body leave a specific impression on the pulse. Figure E28-9 depicts an early description, from a scroll, of pulse diagnosis. There are at least 28 specific types of pulse abnormalities. The pulse is evaluated by placing subtle pressure by the three middle fingers on three points on the radial pulse. When the pulse is strong and regular, the person is considered to be in good health. The traditional Chinese clinician can evaluate six organs on each wrist.

Figure E28–9 Ancient Chinese description of pulse diagnosis.

The Chinese have used iron balls for health since the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). The balls, originally solid, today are hollow with a sounding plate inside them. Each pair consists of one that produces a high tone and the other a low tone. The iron balls are believed to enhance the user’s health and well-being. By moving the iron balls with the fingers, various acupuncture points on the hand are stimulated, resulting in increased circulation of vital energy and blood to the internal organs. Those who use these balls believe that, with daily use, the brain can be kept in good health with improved memory, fatigue will be relieved, and life will be prolonged.

Another major concept in traditional Chinese medicine is the five element theory, also known as the five phases (wu xing). This theory is an attempt to classify phenomena in terms of five quintessential processes represented by wood, fire, earth, metal, and water. Each phase has qualities and functions that describe the various processes in the body and their interactions with the environment. The phases are as follows:

• Earth: solid and quiet; characterizes the spleen, stomach, melancholy, sweet taste, and damp weather

• Metal: firm and strong; characterizes the lung, colon, grief, pungent taste, and dry weather

Traditional Chinese healers use this theory to diagnose and treat illness. Often plotted on a circle, the five phases show a unity in the world and in the body. Many conditions correspond to the five phases. Table 28-2 lists some of the medically relevant associations.

In addition to acupuncture, acupressure and massage are also important aspects of the traditional Chinese healing arts. Acupressure, or dian hsueh, is the forerunner of the Japanese technique called shiatsu. Acupressure is the technique of transferring energy from the therapist’s body directly into the patient’s system by pressing thumb and hands into the patient’s vital areas. Acupressure involves the application of deep pressure to the same points along the channels used in acupuncture. Once a point is located, rotating pressure is applied for 10 to 15 seconds, released, and then repeated as often as the therapist believes necessary. Massage (tui na), in contrast, focuses primarily on the muscle masses, ear, abdomen, foot, and spine. Massage offers the energy of acupuncture, the serenity of meditation, and spiritual refreshment. Tui na stimulates circulation and energy within the body, activates and drains the lymph, tones the muscles, and enhances nerve function.

Tui na therapy is accompanied by cupping, a technique called ba guan, in which glass or bamboo cups containing small amounts of alcohol are applied to the areas of disease and the alcohol is ignited, creating a vacuum inside. The underlying tissue swells up, and the vacuum pressure draws out heat, damp, or wind energies. This technique has been adapted by many other ethnic groups. Figure E28-10 shows the glass cups and a modern suction device for their application.

Figure E28–10 Ba guan (cupping) devices.

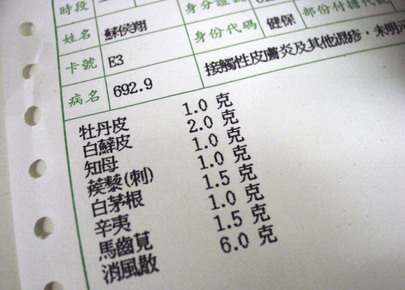

Chinese herbal therapy encompasses eight methods: sweating, vomiting, purging, harmonizing, warming, removing, supplementing, and reducing. There are 5767 herbal remedies known in traditional Chinese medicine, fewer than 10% of which are commonly used currently. Through clinical experience, Chinese medicine recognizes that each herbal remedy has an affinity for a particular meridian or organ. If an illness is caused by heat, cooling with herbal therapy is used; if caused by a deficiency, drugs that restore are used. In a manual of Chinese herbal remedies, each herb is listed as to the part of the plant (P) used, the taste and nature (T&N), the meridian (M) or organ affected, the actions (Act), the amount and form (A&F) of use, and the cautions and contraindications (C&C). For example2:

• Acorus gramineus (Japanese sweet flag)

• A&F: 3 to 6 g (fresh 9 to 24 g) as decoction, pill, or powder

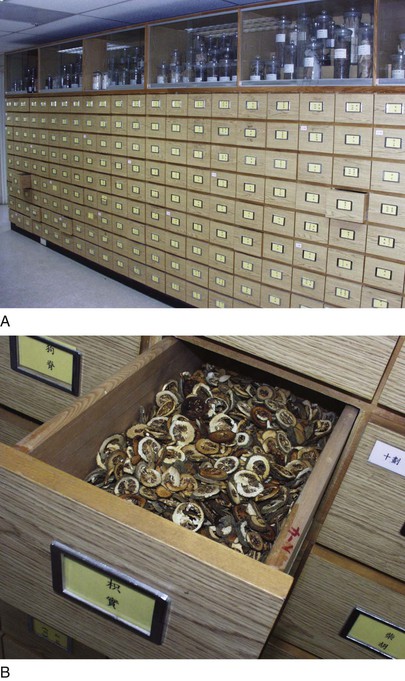

The photograph in Figure E28-11 was taken in a traditional Chinese herbal pharmacy in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Note the prescription written in Chinese, which is necessary to purchase these herbal medications. Figure E28-12 shows the modern herbal pharmacy at the China Medical College in Taichung, Taiwan. Figure E28-13 shows an automated prescription for herbal medications.

Figure E28–13 Computer-generated herbal medication prescription.

The use of medicinal herbs is prevalent and growing. The health care provider must be cognizant of the commonly used herbs and their benefits and limitations. Some herbs can interfere with prescribed medications and with surgery. Bleeding is a common problem. Certain antioxidants may interfere with chemotherapy. The use of medicinal herbs in the West goes back to the days of Paracelsus (1493–1541), who said, “The dose determines the poison.” More clinical trials of safety and efficacy of medicinal herbs are needed to help understand the active ingredients and herb actions.

Concluding Thoughts

CAM therapies have long played a key role in health care. Most health care providers have failed to recognize the magnitude of these forms of healing. Many of the therapies, however, are not based on any sound medical knowledge. Some have been derived from ethnic and folk traditions, semireligious cults, metaphysical movements, and health care groups who rebel against technology and the perceived impersonality of twenty-first century medical care. Unfortunately, marketing terms such as “miracle cure,” “new discovery,” and “satisfaction guaranteed” attract patients looking for cures for diseases for which there are no cures. “Purify,” “detoxify,” and “energize” sound impressive, but they are often used to cover up the lack of scientific proof of efficacy. Finally, clinicians must advise patients that the word natural does not always mean that the therapy is safe, and these products may have druglike effects that may be deleterious to their health and have dangerous interactions with prescribed medications. Therefore, clinicians should look for solid scientific studies. A lack of solid evidence does not always mean these treatments do not work, but it does mean they have not been proven effective.

This chapter has introduced the health care provider to the richness of several of these CAM therapies. Ideally, the health care provider is better prepared to deal with patients of diverse backgrounds who use CAM and with the challenges of caring for those patients in the United States. The provider must be open-minded with regard to these therapies and able to incorporate alternative and complementary therapies into Western medicine. All health care providers must become familiar with CAM practices, the efficacies of the various practices, and the potential risks and benefits from their use.

Bibliography

Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement Online. 1997;15(5):1 http://consensus.nih.gov/1997/1997Acupuncture107html.htm.

Ang-Lee MK, Moss J, Yuan CS. Herbal medicines and perioperative care. JAMA. 2001;286:213.

Cardini F, Weixin H. Moxibustion for correction of breech presentation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1998;280:1580.

Chen K, Cui Y. Handbook of Chinese auricular therapy. Foreign Languages Press: Beijing; 1997.

Chenot JF, et al. Use of complementary alternative medicine for low back pain consulting in general practice: a cohort study. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7(1):42.

Cherkin D, et al. A comparison of physical therapy, chiropractic manipulation, and provision of an educational booklet for the treatment of patients with low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1021.

Cohen MR, Doner K. The Chinese way to healing: many paths to wholeness. Perigee: New York; 1996.

Deihl DL, et al. Use of acupuncture by American physicians. J Altern Complement Med. 1997;3:119.

De Smet PA. Herbal remedies. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:2046.

Eisenberg DM. Advising patients who seek alternative medical therapies. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:61.

Eisenberg DM, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States: prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:246.

Eisenberg DM, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569.

Ernst E. The role of complementary and alternative medicine. BMJ. 2000;321:1133.

Freund PES, McGuire MB. Health, illness, and the social body: a critical sociology. ed 2. Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ; 1995.

Gray CM, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use among health plan members: a cross-sectional survey. Eff Clin Pract. 2002;5:17.

Hager M. Education of health professionals in complementary/alternative medicine. Josiah Macy, Jr. Foundation: New York; 2001.

Hypericum Depression Trial Study Group. Effect of Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s wort) in major depressive disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;287:1807.

Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Medical pluralism in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:189.

Kaptchuk TJ, Eisenberg DM. Varieties of healing: a taxonomy of unconventional healing practices. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:196.

Kessler DA. Cancer and herbs. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1742.

Kessler RC, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135:262.

Kjellgren A, et al. Wellness through a comprehensive Yogic breathing program—a controlled pilot trial. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7(1):43.

Leach RA. The chiropractic theories: a synopsis of scientific research. ed 2. Williams & Wilkins: Baltimore; 1986.

MacPherson H. Fatal and adverse events from acupuncture: allegation, evidence, and the implications. J Altern Complement Med. 1999;5:47.

Marcus DM. How should alternative medicine be taught to medical students and physicians? Acad Med. 2001;76:224.

Maxion-Bergemann S, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine costs—a systematic literature review. Forsch Komplementärmed. 2006;13(2):42.

McLaughlin C, Hall N. Secrets of reflexology. Dorling Kindersley: East Sussex, UK; 2002.

Monte T. World medicine: the East-West guide to healing your body. GP Putnam’s Sons: New York; 1993.

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Complementary and Alternative Medicine Funding by NIH Institute/Center. [Available at] http://nccam.nih.gov/about/budget/institute-center.htm?nav=gsa [Accessed September 15, 2013] .

Niggemann B, Gruber C. Side-effects of complementary and alternative medicine. Allergy. 2003;58:707.

Novey DW. Clinician’s complete guide to complementary medicine. Mosby: St. Louis; 2000.

Oschman JL. Energy medicine: the scientific basis. Churchill Livingstone: Edinburgh; 2000.

Reginster JY, et al. Long-term effects of glucosamine sulfate on osteoarthritis progression: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2001;357:251.

Rubik B. The biofield hypothesis: its biophysical basis and role in medicine. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8:703.

Sharma HM, Triguna BD, Chopra D. Maharishi Ayur-Veda: modern insights into ancient medicine. JAMA. 1991;265:2633.

Shen J, et al. Electroacupuncture for myeloablative chemotherapy-induced vomiting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;284:2755.

Warber SL, et al. Standards for conducting clinical biofield energy healing research. Altern Therap Health Med. 2003;9(3):A54.

Warner JW, Fan MD. A manual of Chinese herbal medicine: principles and practice for easy reference. Shambhala Publications: Boston; 1996.

White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. Interim progress report. White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy: Washington, DC; 2001.

White LB, Foster S. The herbal drugstore. Rodale: Emmaus, Penn; 2000.

Yamashita H, et al. Systematic review of adverse events following acupuncture: the Japanese literature. Complement Therap Med. 2001;2:98.

Young JH. The development of the Office of Alternative Medicine in the National Institutes of Health, 1991–1996. Bull Hist Med. 1998;72:279.

1 Policies of House of Delegates-I-95; H-480.973; BOT Rep. 15-A-94, Reaffirmed and Modified by Sub. Res. 514, I-95.

2 Adapted from Warner and Fan (1996).