2 Understanding basic educational principles

Be fair to your students

We have used the acronym FAIR. Be FAIR to your students by providing:

• Feedback. Give feedback to students as they progress to mastery of the expected learning outcomes.

• Activity. Engage the student in active rather than passive learning.

• Individualisation. Relate the learning to the needs of the individual student.

• Relevance. Make the learning relevant to the students in terms of their career objectives.

Feedback

• Clarifies goals. It highlights what is expected of the learner.

• Reinforces good performance. It has a motivating effect on the learner and may reduce anxiety.

• Provides a basis for correcting mistakes. It enables learners to recognise their deficiencies and helps to guide them in their further study.

It has been demonstrated that academic achievement in classes where effective feedback is provided for students is considerably higher than in classes where this is not so. As Hattie and Timperley (2007) reported, the most powerful single thing that teachers can do to enhance achievement of their students is to provide them with feedback.

1. Give an explanation. In providing feedback, give learners an explanation as to what they did or did not do to meet the expectations. Simply giving a grade or mark in an examination or indicating that learners are right or wrong is less likely to improve their performance. The aim is to help the learner reflect on their performance and to understand the gaps in their learning.

2. Ensure the feedback is specific. Provide learners with feedback about their performance against clearly defined learning outcomes. Informing learners how they compare to their peers or informing them in general terms that they lack competence in an area has little value.

3. Feedback should be non-evaluative. Feedback should be phrased in as non-evaluative language as possible. It is not helpful, for example, to inform learners that their performance was ‘totally inadequate’.

4. Feedback should be timely and frequent. Feedback is more effective when learners receive it immediately than when it is delayed and provided in a later class or session. We have found that providing students with a feedback session immediately following an Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is a useful and powerful learning experience.

5. Prepare adequately in advance. Ensure all the evidence is available with regard to the student’s performance before an attempt is made to provide them with feedback. The teacher should be in a position to provide feedback from first-hand experience with the student.

6. Feedback should help learners to plan their further study. Assist learners to plan their programme of further learning based on their understanding of where they are at present. This may involve giving them specific reading material or organising further practical or clinical experiences appropriate to their needs.

7. Help the learner to appreciate the value of feedback and how to interpret it. A small number of learners may find it difficult to accept and act on feedback provided. One strategy that can help is to ask the learner, before the actual content of the feedback is considered, to reflect orally or in writing on their attitude to being given the feedback.

8. Encourage learners to provide feedback to themselves. Feedback is usually thought of as something that is provided exclusively by teachers. Students should be encouraged to assess and monitor their own performance. Ask the learner what they think they have done well and where they think there are problems. Learners can be provided with tools to assist them to assess themselves. Following an OSCE, for example, students can be given a copy of their marked OSCE checklist, a video of their performance and a video demonstrating the expected performance at the OSCE station.

Activity

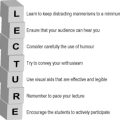

• Where lectures are scheduled, engage the audience to reflect on and respond to what is being discussed. An electronic audience response system, such as those seen in television game shows, or coloured cards can be used as described in Chapter 21.

• Small group teaching, by its nature, is more interactive but guard against it regressing into mini tutorials. Learners should actively engage with other group members and with the teacher who acts as the facilitator of the discussion rather than the presenter of information – ‘the guide on the side rather than the sage on the stage’.

• In the clinical context ensure that learners are not simply passive observers. Learners can be given specific roles and be encouraged to be actively involved in a patient care activity.

• Independent learning resources recommended for use by students, whether in print or online, should be interactive. Available texts or resources can be enriched by the teacher through the addition of meaningful activities that actively engage the student.

• The use of technologies such as models and simulators can contribute to active learning. To assist the learners to make full use of the resources, it is useful to provide support material and guidance in the form of print, audiotapes, video tapes or computer programmes. Activities may be programmed into the simulator.

• Ensure that portfolios involve an active reflective process and are not simply a log or rote documentation of activities carried out by the learners. They should not be seen as a chore with no attempt made to distil general principles or practice points. Learners should reflect on the task and document what they have learned in the process.

Individualisation

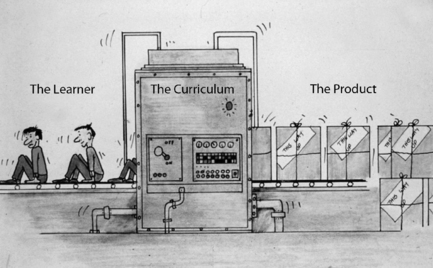

Teachers have had to cope in medical schools with large classes of students and have had to design the learning experiences and programmes accordingly. As illustrated in Figure 2.2, students, like the raw material entering a factory, pass through a standard process emerging as a product with a uniform specification. There has been little opportunity to cater for the needs of the individual student. Students have different requirements in terms of:

• motivation and what drives their learning

• learning goals and career aspirations

• mastery of the course learning outcomes on entry to the course

Today, faced with the challenge of individualising learning, the teacher has a number of options:

• The issue of individualisation can be ignored with the teacher and the education programme addressing the needs of the body of students as a whole. This has disadvantages as illustrated in the following example. An analysis of the examination results in a medical school showed that two thirds of the class answered questions on a specific topic incorrectly. As a response to this finding, a decision was taken to restore a number of lectures on the topic which had previously been omitted from the curriculum. This may or may not address the performance problem with regard to the students who had given the wrong answers to the questions. It penalised however the third of the class who had mastered the subject and for whom the revised lecture course was not appropriate.

• A range of learning opportunities can be provided from which students can select those which best suit their personal needs. The teaching programme may be arranged so that students can choose to attend a lecture on a subject, view a podcast of the lecture, engage in collaborative problem-based learning with their peers, or work independently using an online learning programme. The extent and range of learning opportunities included in the menu for the students will depend on the time and resources available. A move in this direction is supported by the increasing availability of e-learning resources.

• Learning resources or learning opportunities can be adapted or prepared so that the student’s learning experience, as they work through the programme, is personalised to their individual needs. If students answer incorrectly a question embedded in a learning programme, or if they indicate they have difficulty understanding the message being conveyed, a further explanation and additional material that addresses the aspect of the topic is provided immediately.

• When learning experiences are scheduled in the programme, such as a session with a simulator, the time allotted for an individual student is not fixed, but is the length of time necessary for the student to master the required skills. Some students or trainees will take longer to master the skills than others.

• With the expansion of medical knowledge and the danger and problem of information overload, students can no longer be provided with in-depth learning in all aspects of medicine. Time can be scheduled in the learning programme when students have a greater element of choice in the subjects studied. Up to a third of the curriculum time may be allocated for electives or student selected components (SSCs). This is discussed further in Chapter 17.

• Portfolio assessment encourages students to create their own learning programme and to demonstrate their learning in relation to the core and other areas they choose to study. This is described in Chapter 31.

Relevance

Pressures to constantly examine the relevance of what is covered in the curriculum include:

• the rapid expansion of medical knowledge and concerns about information overload

• the introduction of new subjects such as genetics and telemedicine

• important learning outcomes which have been previously ignored such as communication skills and professionalism.

• If students understand why they are addressing a topic they will be more motivated to learn. Adding relevance to teaching creates a powerful and rich experience. In general students learn more rapidly if they are motivated and realise that what they learn will be useful to them in the future.

• More effective learning results when the student is engaged in applying theory to practice. This requires the student to reflect and think about why they are learning a subject, which in turn dramatically improves the effectiveness of their learning. Inert knowledge that is not applied remains only in the short-term memory.

• A set of clinical cases or presentations used as a framework for the curriculum provides a scheme around which students, from the early years of their studies, can construct their learning in the basic and clinical sciences.

• Relevance can be applied as a criterion to inform a decision as to whether a topic or subject should be incorporated in the curriculum. More has to be learned but the time available in the curriculum remains constant.

• A vertically integrated curriculum with clinical experiences including attachments introduced in the early year of the course (Chapter 15).

• A problem-based approach where students’ learning is structured round clinical problems (Chapter 14).

• The use of virtual patients where a student is presented online with a patient whose problem relates to the subject they are studying (Chapter 26).

• A clear statement of expected exit learning outcomes and communication with the student as to how their learning experiences will contribute to their mastery of the learning outcomes (Chapter 19).

• Examinations designed to assess the student in the context of clinical practice. A short patient scenario may be used as the stem for an MCQ in a basic science question paper. Portfolio assessment (Chapter 31) can be designed to support relevance in the student’s learning.

• New technologies such as simulators provide for the student a more realistic learning experience (Chapter 25).

Reflect and react

1. Recognise in your own teaching the importance of feedback. Ask your students or trainees how they perceive the feedback provided by you. By paying attention to feedback, you can promote a culture of positive improvement in your learners.

2. Look at your own teaching and assess the extent to which students are actively engaged in what they perceive as meaningful activities. Documentation in a logbook of the cases they have seen involves the students in an activity, but if the student does not perceive the benefit of the exercise, it can be seen as a waste of time.

3. Individualisation and tailoring a learning programme to meet a student’s individual needs offers many benefits but is difficult to achieve in practice. Can you adopt in your own teaching programme any of the suggestions in this chapter that might allow you to take into account the differing needs of your students or trainees?

4. Feedback, activity and individualisation are all key ingredients of a teaching programme, but if relevance is missing your teaching is unlikely to be successful. Do you pay sufficient attention to ensuring that students recognise the relevance of their learning experiences?

Harden R.M., Laidlaw J.M. Effective Continuing Education: The CRISIS Criteria. AMEE Guide No. 4. Med. Educ.. 1992;26:408-422.

Hattie J., Timperley H. The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research. 2007;77:81-112.

An important review of the educational uses of feedback.

Kaufman D.M. Applying educational theory in practice. In Cantillon P., Wood D., editors: ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine, second ed., Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. (Chapter 1)

A short and helpful description of how to bridge the gap between education theory and practice.

Laidlaw J.M., Harden R.M. Impact of technology on the education of health care professionals. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care. 1987;3:67-82.