Chapter 47 Uncommon malignant tumors of the skin

1. What is an epithelioid sarcoma?

Epithelioid sarcoma is an exceedingly rare high-grade malignancy of unknown lineage with no normal cellular counterpart. The tumor has an indolent course but a high potential to metastasize. It is remarkable for being a difficult diagnosis, both clinically and histologically, resulting in a high frequency of initial misdiagnosis. Diagnosis is reached on average 8 years after initial clinical presentation.

3. How does epithelioid sarcoma present?

It presents as a painless, firm, slow-growing, intradermal or subcutaneous nodule, often ulcerated, usually on the volar surface of the fingers or palms. It occurs most frequently on the distal upper extremity, but it may also occur on the lower extremities and occasionally in the trunk or head and neck region. Epithelioid sarcoma has a tendency to spread locally through lymphatic channels or along fascial planes, and may give rise to multiple local nodules. The clinical differential diagnosis includes mycobacterial or deep fungal infection, squamous cell carcinoma, and other soft tissue sarcomas. The male-to-female ratio is approximately 2:1, and it affects mainly young adults.

4. How is the diagnosis of epithelioid sarcoma made?

The diagnosis of epithelioid sarcoma is made by typical histologic features. The tumor is composed of malignant, eosinophilic, epithelioid and spindle cells arranged in nodules that often demonstrate central necrosis. Immunohistochemistry, special stains, and tissue culture are used to assist the diagnosis. The tumor cells demonstrate staining with both mesenchymal markers (vimentin), as well as epithelial markers (keratins and epithelial membrane antigen).

5. How are epithelioid sarcomas treated?

Early radical local excisional surgery is required. The local recurrence rate has been reported to range from 35% to 77%. Multifocal recurrences are common because the tumor spreads insidiously along tendons, fascial planes, nerves, and blood vessels. Adjuvant radiotherapy is often used to lower the risk of local recurrence; however, amputation is sometimes required. Chemotherapy with ifosfamide and doxorubicin is recommended for metastatic disease.

7. What are the prognostic factors of epithelioid sarcoma?

10. How does angiosarcoma of the scalp and face in the elderly present?

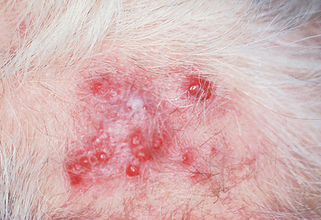

It presents as an erythematous or hemorrhagic bruiselike patch on the central face or scalp, which spreads centrifugally and evolves into nodules that bleed easily and ulcerate (Fig. 47-1). There is often extensive infiltration, and the extent of the tumor is often underestimated clinically.

11. What are the clinical course and prognosis for angiosarcoma?

In the largest reported series of 72 patients, only 12% survived for 5 years. Metastases to the cervical nodes and hematogenous metastases to the lungs, liver, and spleen occur. Because of their rarity, there are no clear definitive or significant prognostic factors identified for angiosarcoma, but histologic grade, tumor diameter, depth of invasion, positive margins, metastases, and tumor recurrence are potential predictors of outcome.

12. Is there an effective treatment for angiosarcoma?

Early diagnosis and complete surgical excision offer the best chance of survival. However, because the lesions tend to be multicentric, extensive, and rapidly growing over the face and scalp, surgical excision is rarely successful. A combined-modality approach is often used, including excision of disease with negative margins if possible, with adjuvant radiotherapy. Chemotherapy is usually recommended in cases of systemic disease.

13. What is the clinical presentation of angiosarcoma arising in chronic lymphedema?

This rare tumor, also called Stewart-Treves syndrome, arises as cutaneous and subcutaneous firm, coalescing, violaceous nodules on a background of nonpitting edema, often in the inner aspect of the upper arm. It occurs on average 10 years following mastectomy and lymphadenectomy (range 1 to 30 years). It is less commonly associated with filarial, congenital, traumatic, or idiopathic lymphedema.

15. What are the histologic features of angiosarcomas?

Angiosarcomas are composed of an anastomosing network of well-formed, irregular vascular channels, often lined by flattened endothelial cells. They exhibit a highly infiltrative pattern, dissecting and splitting collagen bundles. Poorly differentiated angiosarcomas may closely resemble carcinomas or other soft tissue sarcomas, with only subtle vascular lumen formation.

16. What is Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC)?

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), also known as primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, is an aggressive malignant neoplasm. The tumor was initially thought to arise from Merkel cells, receptors of mechanical stimuli with a high density on hairless skin. However, the tumor is now thought to arise from a less–well-differentiated progenitor cell of probably epithelial origin.

18. What is the pathogenesis of MCC?

MCC is extremely rare before age 50 years, and the incidence increases steeply after 65 years of age, suggesting an accumulation of oncogenic events. Immunosuppression is likely involved in the pathogenesis, as MCC incidence is increased approximately 11-fold for persons with AIDS and 5-fold for persons who have undergone organ transplantation. The majority of tumors present on sun-exposed areas, and the risk of MCC may be particularly high with prior psoralen and ultraviolet A treatment (PUVA) suggesting that UV radiation contributes to the etiology of this malignancy. More recently, the viral genome of polyomavirus (Merkel cell polyomavirus) was detected in MCC, and there is accumulating evidence to suggest a direct mechanistic role for the virus in the pathogenesis of MCC.

19. Can any other tumors be microscopically confused with MCC?

Yes. MCC is composed of undifferentiated basaloid, small, blue cells with hyperchromatic nuclei, scant cytoplasm, and frequent mitotic figures, and it may be confused with metastatic small cell carcinoma (oat-cell carcinoma) of the lung, malignant lymphoma, sweat gland carcinoma, metastatic carcinoid tumors, and Ewing’s sarcoma. Electron microscopy may be helpful in order to highlight the dense core neurosecretory granules seen in MCC.

20. What special stains are available to diagnose MCC?

MCC often has a characteristic paranuclear “dot” that stains with cytokeratin, especially cytokeratin 20. MCC also stains positively for various neuroendocrine markers, such as synaptophysin, chromogranin A, neuron-specific enolase, calcitonin, and vasoactive intestinal peptides. Epithelial membrane antigen is also often positive. MCC are usually not decorated with thyroid transcription factor–1 (TTF-1), which is an important finding because most small cell carcinomas of the lung are TTF-1 positive.

21. How do you treat MCC?

Wide local excision with surgical margins up to 3.0 cm has been recommended. In cosmetically sensitive areas, Mohs surgery may be helpful, although research is limited. Other considerations at the time of surgery include assessment of regional lymph nodes (lymph node dissection) and irradiation. Chemotherapy is used for nodal, metastatic, and recurrent MCC, and common agents used are cyclophosphamide, anthracyclines, and cisplatin. Local recurrences occur in 40% of patients.

23. What is the overall prognosis?

The prognosis of MCC is related to the stage of disease, with a 5-year survival rate ranging from 81% in patients with localized small tumors, to 11% in patients with metastatic disease. More than half of patients experience recurrence, usually within 1 year of treatment. All patients need close follow-up after excision.

24. What are the clinical features of microcystic adnexal carcinoma (MAC)?

MAC is a locally aggressive tumor that shows histologic evidence of follicular and sweat duct differentiation. It classically presents as a slow-growing, firm, ill-defined plaque or nodule on the head and neck, most often on the upper lip (Fig. 47-3). Numbness, paresthesia, burning, discomfort, or, rarely, pruritus of the affected area may be reported, and are likely related to the fact that the tumor frequently exhibits perineural invasion. Histologically, it must be differentiated from morpheaform basal cell carcinoma, desmoplastic trichoepithelioma, or syringoma.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans

27. What is dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans?

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans (DFSP) is a firm, locally aggressive tumor that exhibits massive proliferation of spindle cells in the dermis and subcutaneous fat. These cells form intersecting bundles with a characteristic storiform (cartwheel) arrangement. The pigmented variant is called Bednar tumor.

29. Describe the clinical features of DFSP.

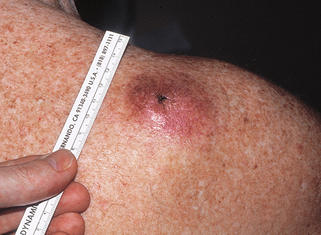

DFSP presents as a slow-growing, elevated, and indurated (often multinodular) plaque that is flesh-colored to red-brown or blue (Fig. 47-4). It may occasionally present as an atrophic lesion and be mistaken for a scar. It most commonly occurs on the trunk and extremities on young to middle-aged adults, but it may be seen on the head and neck.

31. How is DFSP treated?

Adequate local excision is the treatment of choice. Mohs micrographic surgery affords the highest cure rates (>95%). Patients with locally aggressive tumors that are not resectable or with metastatic disease are most commonly treated with imatinib mesylate, which targets a specific translocation between chromosomes 17 and 22 that is found in most cases of DFSP.

32. What is an atypical fibroxanthoma (AFX)?

AFX is a superficial mesenchymal dermal tumor that microscopically shows high-grade cytologic atypia. It most commonly presents in the elderly as a nondistinct solitary dome-shaped nodule in sun-damaged skin, usually of the head and neck (Fig. 47-5). Ulceration is variably present. Histologically, it demonstrates a cellular dermal tumor with an epidermal collarette. Skin adnexa are generally surrounded but not destroyed by the tumor, and the deep margin is generally pushing rather than infiltrative. The tumor is composed of spindle and epithelioid cells arranged in disordered fascicles, with striking pleomorphism and atypia of the cells and numerous mitosis.

Malignant fibrous histiocytoma

35. What is a malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH)?

MFH is a malignant soft tissue tumor arising in the deep soft tissue. It is thought by several authors not to represent a diagnostic entity, but a common, final pathway of many tumors, as its features are shared by a variety of poorly differentiated malignant neoplasms. The term MFH is now reserved for the small group of truly undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas. The histogenesis has been a cause of an ongoing debate, but it is now accepted that the histiocyte is most likely not the cell of origin of the tumor. More recent studies suggest that MFH is a sarcoma of a poorly defined mesenchymal cell, which may differentiate along histiocytic and fibrocytic lines. The term MFH is being substituted by pleomorphic sarcoma. Histologically, the tumor demonstrates a variable appearance with five subtypes: pleomorphic-storiform, myxoid (also called myxofibrosarcoma), giant cell, angiomatoid, and inflammatory. The histologic diagnosis is one of exclusion based on the histologic appearance and special stains, because these histologic patterns may be mimicked by other soft tissue tumors.

38. What are the clinical features of extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD)?

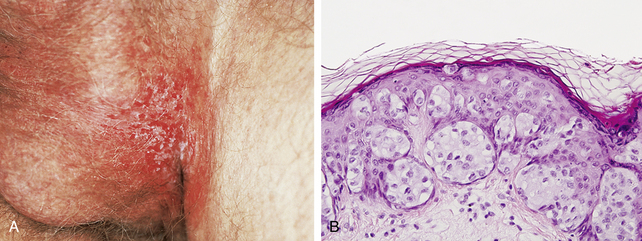

EMPD is a malignant epithelial tumor most often found in the genital region or perineum, which also uncommonly occurs on the axillae, eyelid, ear, anterior chest, and accessory nipples. Nearly all cases of EMPD occur in areas that contain apocrine glands, and, although the histogenesis is not proven, current evidence suggests that they arise from Toker cells. The function of Toker cells is not entirely understood, but based on their distribution, they are likely involved in apocrine gland and breast development. Clinically, EMPD presents as a pruritic, erythematous patch or plaque with oozing and crusting (Fig. 47-6A), which can be confused with dermatitis. It occurs in older adults.

39. Is EMPD associated with underlying malignancies?

Yes. Some cases with a similar clinical and histologic presentation arise when an underlying gastrointestinal or genitourinary adenocarcinoma demonstrates a similar pagetoid spread of epithelial cells. Some authorities refer to those cases that arise in the epidermis without an underlying carcinoma as “primary extramammary Paget’s disease,” and those that arise from an underlying malignancy as “secondary extramammary Paget’s disease.”

40. What is meant by “pagetoid” growth?

This is a histologic term used to describe large, pale cells that demonstrate a scattered growth pattern through the epidermis (Fig. 47-6B). In addition to extramammary Paget’s disease, pagetoid growth is also seen in Paget’s disease of the breast, squamous cell carcinoma in situ (Bowen’s disease), malignant melanoma, and, rarely, sebaceous gland carcinomas. Paget’s disease is named after Sir James Paget (1814–1894), who was among the first to describe this disease in the breast.

41. How is it treated?

Surgical excision with careful margin control. Mohs micrographic surgery can be useful, but the tumor can be multifocal and local recurrences occur.

Key Points: Uncommon Malignant Tumors of the Skin

1. Epithelioid sarcoma is an aggressive tumor that presents on the volar distal extremities of young adults as a slow-growing dermal or subcutaneous nodule.

2. Merkel cell carcinoma is a rapidly growing tumor of the head, face, and neck that frequently metastasizes to regional lymph nodes and is treated with wide local excision (with 3-cm margins), lymph node dissection, and irradiation.

3. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing, multinodular, flesh-colored to red-brown or blue plaque of the trunk and extremities that has a high local recurrence rate after incomplete excision.

43. How does sebaceous carcinoma present?

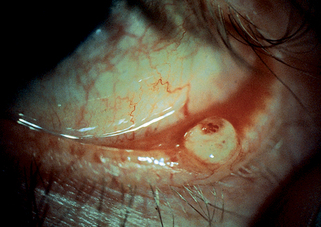

Ocular tumors present as firm nodules (Fig. 47-7). Because they may mimic a chalazion, it is important to biopsy persistent or unusual lesions. Extraocular tumors occur on the head and neck of the elderly. Sebaceous carcinoma is more common in Asians.

48. What are the treatment and prognosis?

Early detection and adequate surgical excision is necessary. Dermal tumors metastasize rarely, whereas subcutaneous tumors metastasize in about one third of patients.