Chapter 8 Uncommon Causes of Stroke

Imaging can be invaluable when evaluating patients with stroke of unknown cause. Sometimes it provides the diagnosis, and sometimes clues to guide additional investigations. This chapter illustrates some of the many infrequent causes of stroke and highlights the ways in which neuroimaging can contribute to their identification. For a more comprehensive review on the topic of uncommon causes of stroke, the reader is referred to a monograph edited by Caplan and Bogousslavsky.1

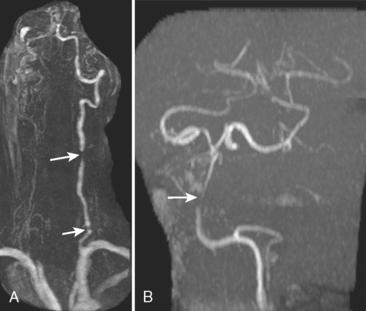

CERVICOCRANIAL ARTERIAL DISSECTIONS

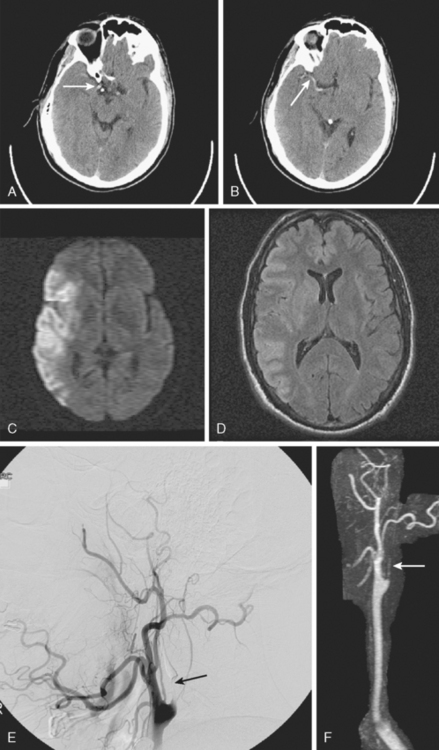

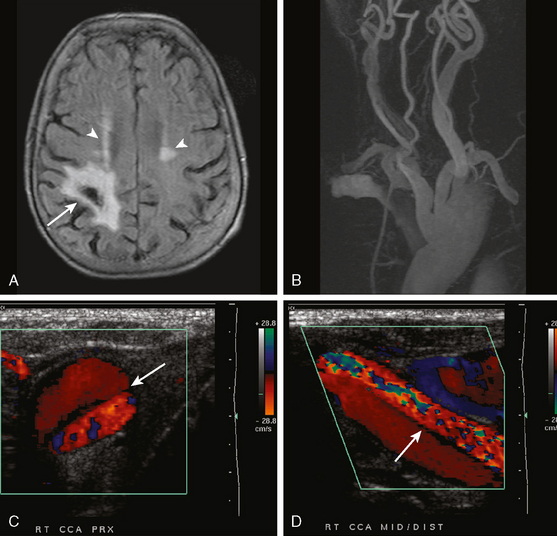

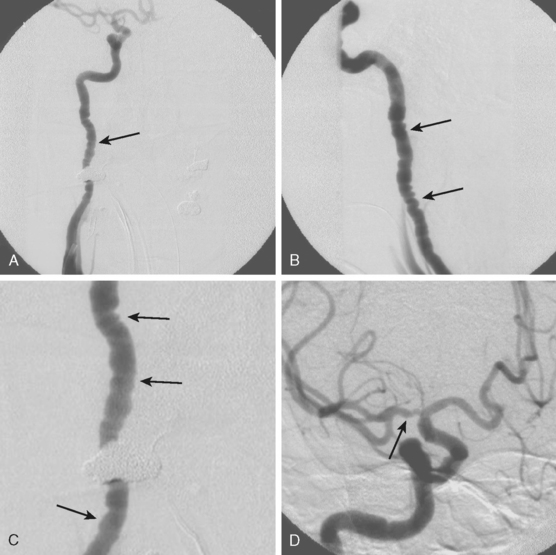

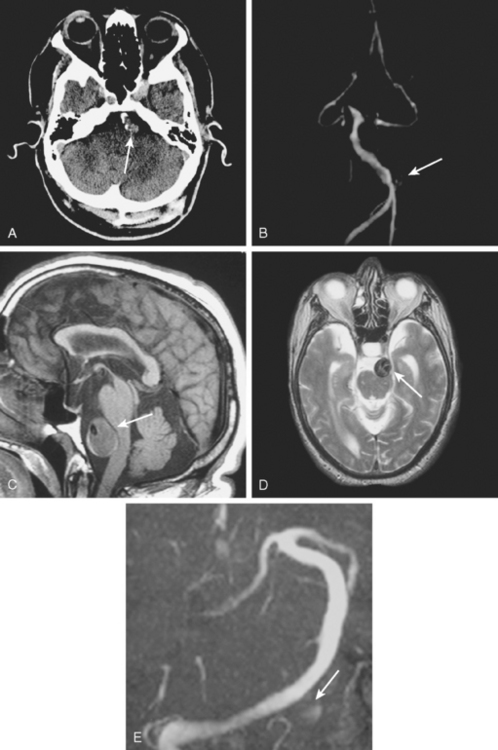

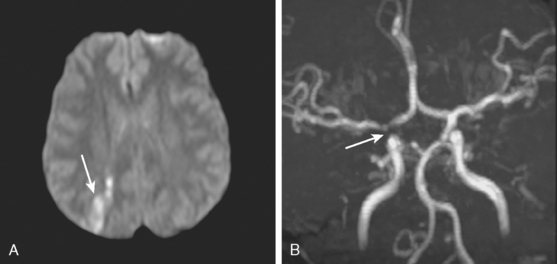

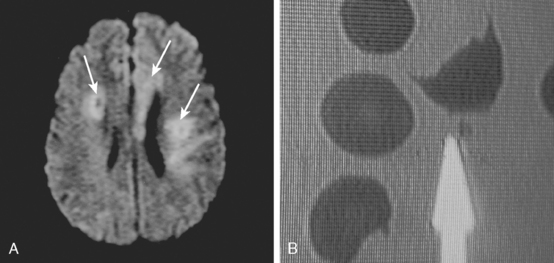

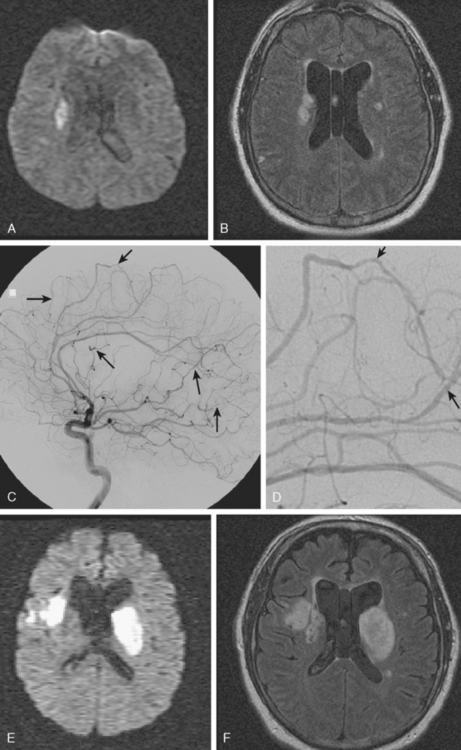

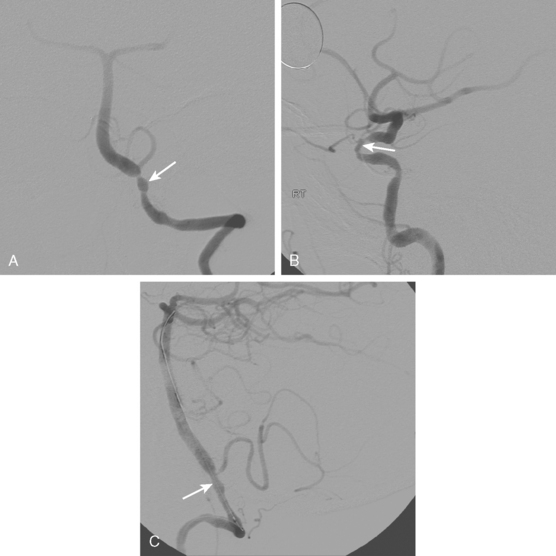

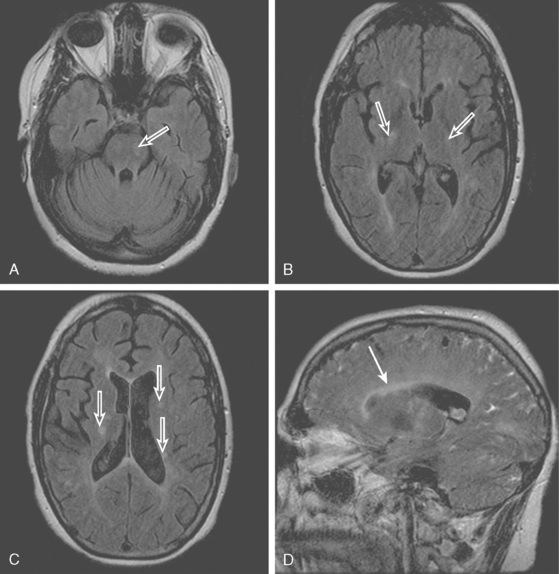

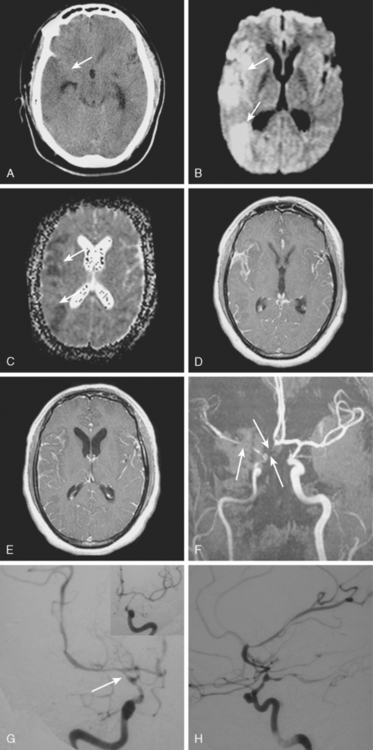

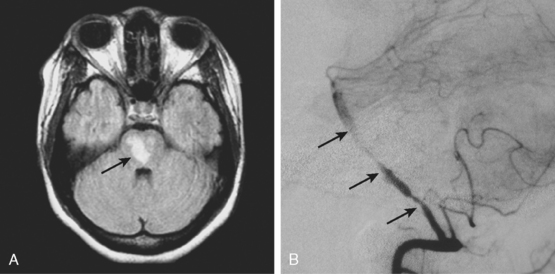

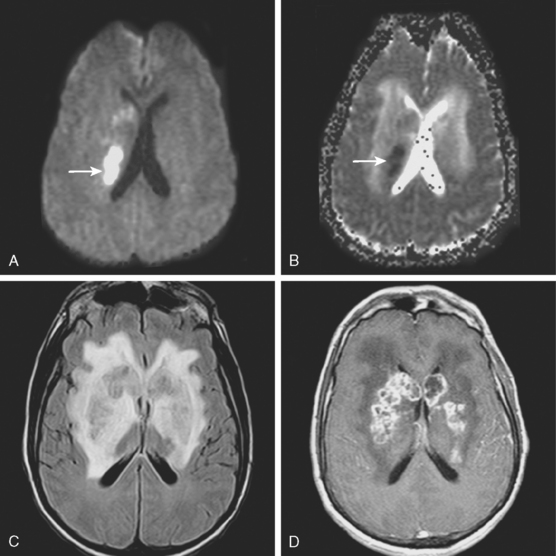

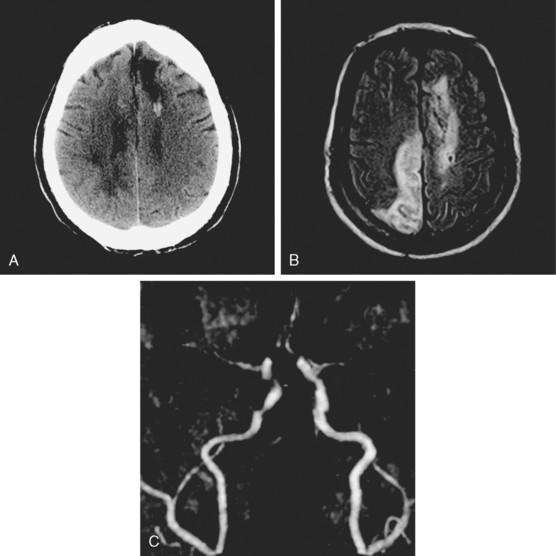

A 41-year-old man with history of smoking and amphetamine use presented to the emergency department with acute confusion, right gaze preference, left homonymous hemianopia, left hemiplegia (involving face, arm, and leg) and marked left-sided neglect. Three hours before the onset of these deficits, he had complained of severe headache and had tried to go to sleep. Upon awakening, the neurological deficits were established. Computed tomography (CT) scan showed a hyperdense sign in the top of the internal carotid and middle cerebral arteries (Figure 8-1, A–B). The patient was emergently taken to the angiographic suite, and a catheter angiogram revealed occlusion of the right internal carotid artery 1.5 to 2 cm beyond its origin (Figure 8-1, E). No revascularization therapy was attempted because of the site of the occlusion, acceptable collateral pathways (the anterior communicating artery and posterior communicating arteries were open), and because the patient started seizing and had to be rapidly transferred to the intensive care unit for anticonvulsive treatment. His blood pressure was augmented with fluids and vasopressors, but he developed a large stroke in the middle cerebral artery territory, as shown on the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan performed within 24 hours of admission (Figure 8-1, C–D). He recovered well but was still moderately disabled at 3-month follow-up. At that time, a magnetic resonance angiogram (MRA) showed persistent occlusion of the right internal carotid artery (Figure 8-1, F).

TABLE 8-1 Angiographic signs of cervical artery dissections.

| Tapered luminal narrowing (string sign) |

| With stenosis |

| With occlusion |

| Pseudo-aneurysm (segmental dilatations) |

| Oval segmental dilatation of the lumen |

| Extraluminal pouch |

| Small dilatation at the end of a string sign |

| Intimal flap* |

| Double lumen |

| High carotid stenosis or occlusion |

* Usually only seen on catheter angiography but sometimes noted on thin axial cuts of magnetic resonance imaging scans.

AORTIC DISSECTIONS

FIBROMUSCULAR DYSPLASIA

DOLICHOECTASIA

MOYAMOYA

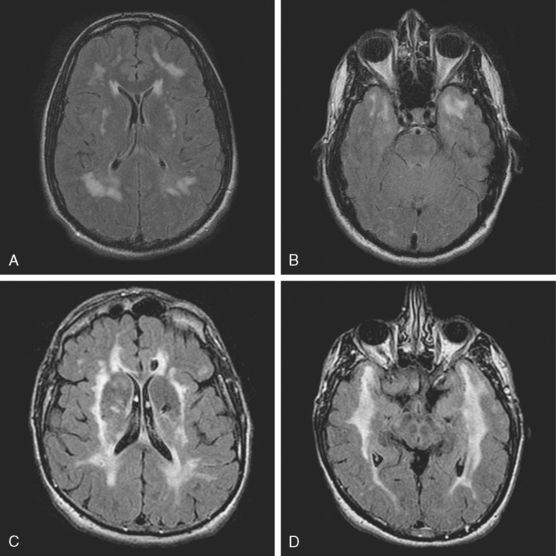

CADASIL

MELAS

REVERSIBLE CEREBRAL VASOCONSTRICTION

HYPERCOAGULABILITY

VASCULITIS

| Primary central nervous system angiitis |

| Susac’s syndrome |

| Cogan’s syndrome |

| Eale’s disease |

| Systemic noninfectious vasculitis |

| Giant cell arteritis |

| Takayasu arteritis |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Polyarteritis nodosa |

| Microscopic polyangiitis |

| Wegener’s disease |

| Churg-Strauss’ disease |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Beçhet’s disease |

| Infectious vasculitis |

| Bacterial (tuberculosis, bacterial meningitis, syphilis) |

| Viral (VZV, CMV, HIV,* etc.) |

| Fungal (cryptococosis, aspergillosis, mucormycosis, candidiasis etc.) |

| Parasitic (cysticercosis) |

| Radiation |

| Drugs of abuse (cocaine, amphetamines)† |

| Tumors and proliferative disorders‡ |

| Infiltrating angiocentric lymphoma |

| Lymphomatoid granulomatosis |

CMV, cytomegalovirus; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus, VZV, varicella zoster virus.

* Most cases are related to a small vessel vasculopathy, which does not include major perivascular or intravascular inflammatory infiltrates (hence, not strictly a vasculitis).80

† Many of these cases may be caused by acute, severe vasoconstriction.

‡ Questionable if this truly can be considered within the category of vasculitis.

Primary Central Nervous System Angiitis

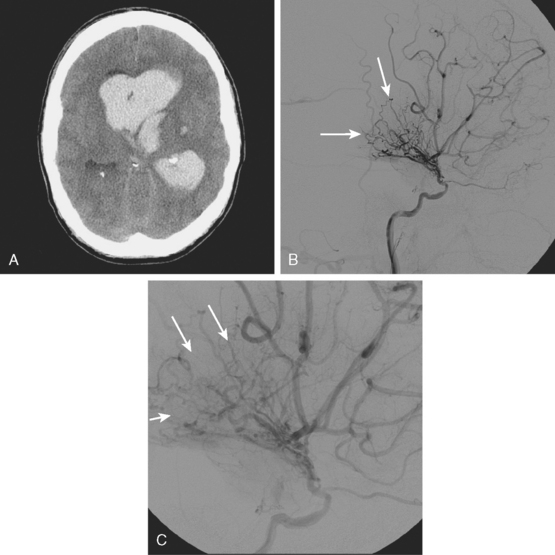

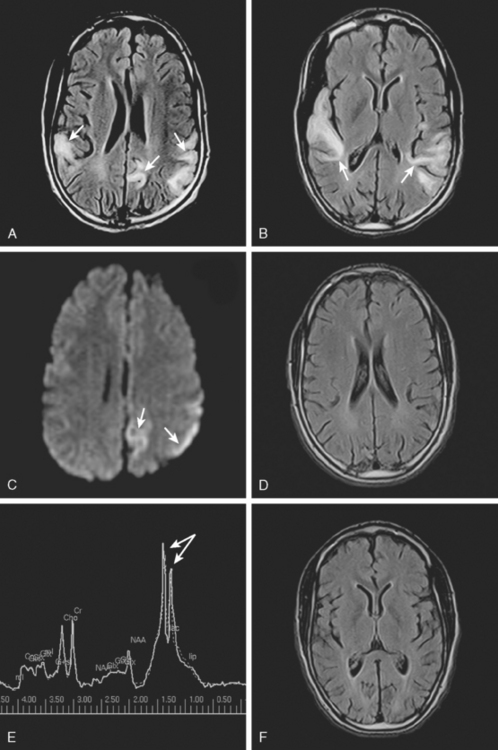

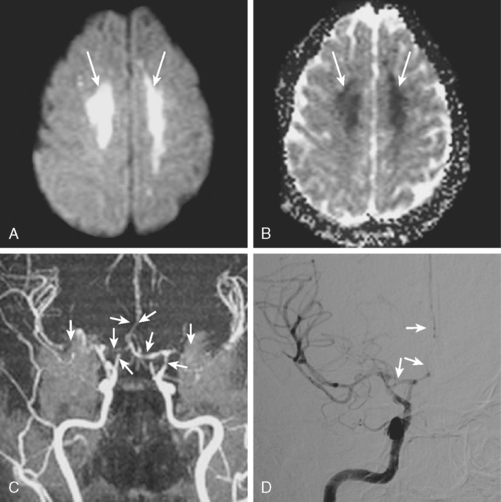

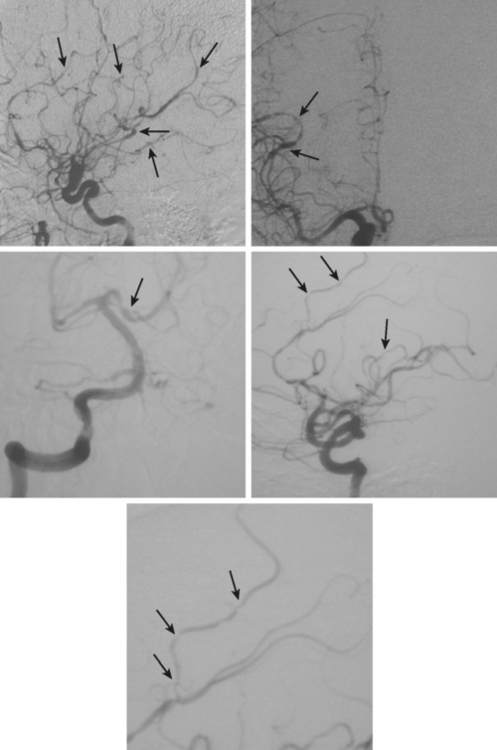

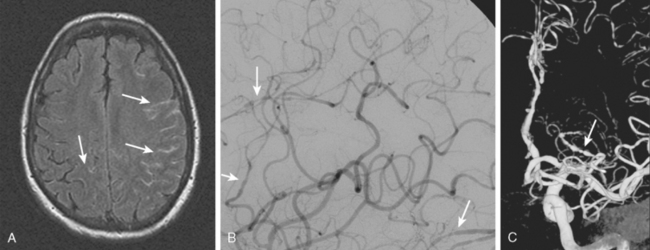

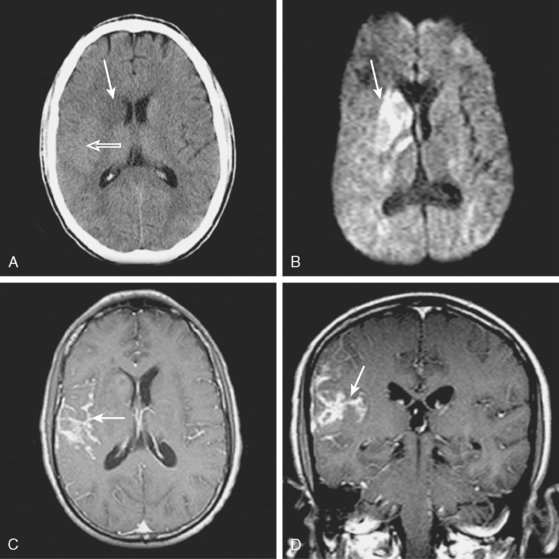

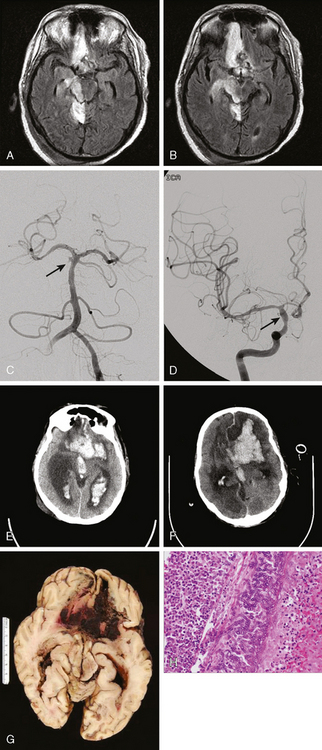

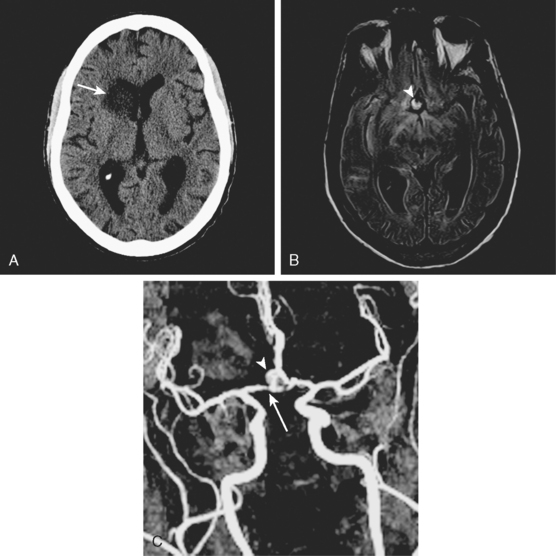

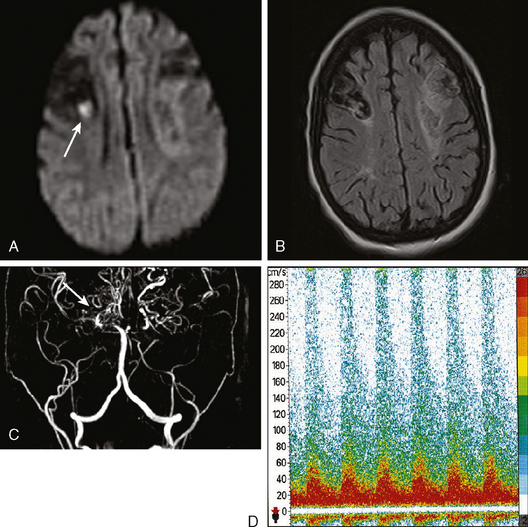

A 53-year-old man with history of biopsy-proved primary central nervous system (CNS) angiitis was transferred from another hospital because of recurrent strokelike episodes. His neurological symptoms had started 3 years earlier when he developed severe headaches and some degree of confusion. MRI of the brain showed scattered subcortical lesions, and his cerebrospinal fluid had inflammatory features (125 cells/mm3 with lymphocytic predominance and normal cell morphology, protein level of 112 mg/dl with normal) glucose content. Double substraction angiography (DSA) revealed multifocal irregularities in large and smaller intracranial arteries. Brain biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of CNS vasculitis. Extensive workup for infection, tumor, and systemic vasculitis was negative. The patient was treated with intravenous corticosteroids with good clinical response. He remained asymptomatic on prednisone until 2.5 months before the current hospitalization when he developed acute dysarthria and left hemiparesis. Brain imaging disclosed a new right subcortical stroke, and noninvasive angiography showed increased signs of vasculitis. The dose of prednisone was increased, but the patient continued to worsen. His attention span declined, and he became more irritable. Over the following 3 months, he had two more episodes of increased dysarthria and incoordination. A third event prompted the hospitalization. MRI of the brain at that time showed a new area of acute ischemia in the right corona radiata (Figure 8-16, A and B). DSA displayed extensive arterial beading in all major intracranial arteries (Figure 8-16, C and D). Despite high-dose intravenous steroids, the patient’s level of alertness worsened over the subsequent week. On the seventh hospital day, he was found stuporous and required intubation for airway protection. He appeared to have a new right hemiparesis. Repeat MRI of the brain showed enlargement of the area of ischemia on the right hemisphere and a new, larger ischemic infarction on the left hemisphere (Figure 8-16, E and F). He was treated with a pulse dose of cyclophosphamide without response. Plasma exchange was also tried unsuccessfully. He became comatose, and after failure to improve over the following 10 days, his family requested withdrawal of life support.

Giant Cell (Temporal) Arteritis

SUSAC’S Syndrome

Infectious Vasculitis

HIV VASCULOPATHY

RADIATION-INDUCED VASCULOPATHY

STROKES FROM SUBSTANCE ABUSE

SICKLE CELL DISEASE

1 Bogousslavsky J, Caplan L. Uncommon Causes of Stroke. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

2 Schievink WI. Spontaneous dissection of the carotid and vertebral arteries. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:898-906.

3 Brandt T, Orberk E, Weber R, Werner I, Busse O, Muller BT, et al. Pathogenesis of cervical artery dissections: association with connective tissue abnormalities. Neurology. 2001;57:24-30.

4 Schievink WI, Parisi JE, Piepgras DG, Michels VV. Intracranial aneurysms in Marfan’s syndrome: an autopsy study. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:866-870.

5 Schievink WI, Roiter V. Epidemiology of cervical artery dissection. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2005;20:12-15.

6 Dziewas R, Konrad C, Drager B, Evers S, Besselmann M, Ludemann P, et al. Cervical artery dissection—-clinical features, risk factors, therapy and outcome in 126 patients. J Neurol. 2003;250:1179-1184.

7 Schievink WI, Mokri B, Piepgras DG, Kuiper JD. Recurrent spontaneous arterial dissections: risk in familial versus nonfamilial disease. Stroke. 1996;27:622-624.

8 Martin JJ, Hausser I, Lyrer P, Busse O, Schwarz R, Schneider R, et al. Familial cervical artery dissections: clinical, morphologic, and genetic studies. Stroke. 2006;37:2924-2929.

9 Silbert PL, Mokri B, Schievink WI. Headache and neck pain in spontaneous internal carotid and vertebral artery dissections. Neurology. 1995;45:1517-1522.

10 Arnold M, Bousser MG, Fahrni G, Fischer U, Georgiadis D, Gandjour J, et al. Vertebral artery dissection: presenting findings and predictors of outcome. Stroke. 2006;37:2499-2503.

11 Paciaroni M, Caso V, Agnelli G. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance and catheter angiography for diagnosis of cervical artery dissection. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2005;20:102-118.

12 Mascalchi M, Bianchi MC, Mangiafico S, Ferrito G, Puglioli M, Marin E, et al. MRI and MR angiography of vertebral artery dissection. Neuroradiology. 1997;39:329-340.

13 Levy C, Laissy JP, Raveau V, Amarenco P, Servois V, Bousser MG, et al. Carotid and vertebral artery dissections: three–dimensional time-of-flight MR angiography and MR imaging versus conventional angiography. Radiology. 1994;190:97-103.

14 Kirsch E, Kaim A, Engelter S, Lyrer P, Stock KW, Bongartz G, et al. MR angiography in internal carotid artery dissection: improvement of diagnosis by selective demonstration of the intramural haematoma. Neuroradiology. 1998;40:704-709.

15 Metso TM, Metso AJ, Helenius J, Haapaniemi E, Salonen O, Porras M, et al. Prognosis and safety of anticoagulation in intracranial artery dissections in adults. Stroke. 2007;38:1837-1842.

16 Lanczik O, Szabo K, Hennerici M, Gass A. Multiparametric MRI and ultrasound findings in patients with internal carotid artery dissection. Neurology. 2005;65:469-471.

17 Benninger DH, Baumgartner RW. Ultrasound diagnosis of cervical artery dissection. Front Neurol Neurosci. 2006;21:70-84.

18 Benninger DH, Georgiadis D, Gandjour J, Baumgartner RW. Accuracy of color duplex ultrasound diagnosis of spontaneous carotid dissection causing ischemia. Stroke. 2006;37:377-381.

19 Koch S, Rabinstein AA, Romano JG, Forteza A. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in internal carotid artery dissection. Arch Neurol. 2004;61:510-512.

20 Koch S, Amir M, Rabinstein AA, Reyes-Iglesias Y, Romano JG, Forteza A. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging in symptomatic vertebrobasilar atherosclerosis and dissection. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1228-1231.

21 Arauz A, Hoyos L, Espinoza C, Cantu C, Barinagarrementeria F, Roman G. Dissection of cervical arteries: long-term follow-up study of 130 consecutive cases. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2006;22:150-154.

22 Guillon B, Brunereau L, Biousse V, Djouhri H, Levy C, Bousser MG. Long-term follow-up of aneurysms developed during extracranial internal carotid artery dissection. Neurology. 1999;53:117-122.

23 Touze E, Randoux B, Meary E, Arquizan C, Meder JF, Mas JL. Aneurysmal forms of cervical artery dissection: associated factors and outcome. Stroke. 2001;32:418-423.

24 Benninger DH, Gandjour J, Georgiadis D, Stockli E, Arnold M, Baumgartner RW. Benign long-term outcome of conservatively treated cervical aneurysms due to carotid dissection. Neurology. 2007;69:486-487.

25 Bassetti C, Carruzzo A, Sturzenegger M, Tuncdogan E. Recurrence of cervical artery dissection. A prospective study of 81 patients. Stroke. 1996;27:1804-1807.

26 Touze E, Gauvrit JY, Moulin T, Meder JF, Bracard S, Mas JL. Risk of stroke and recurrent dissection after a cervical artery dissection: a multicenter study. Neurology. 2003;61:1347-1351.

27 Lee VH, Brown RDJr, Mandrekar JN, Mokri B. Incidence and outcome of cervical artery dissection: a population-based study. Neurology. 2006;67:1809-1812.

28 Dittrich R, Nassenstein I, Bachmann R, Maintz D, Nabavi DG, Heindel W, et al. Polyarterial clustered recurrence of cervical artery dissection seems to be the rule. Neurology. 2007;69:180-186.

29 Schievink WI, Mokri B, O’Fallon WM. Recurrent spontaneous cervical–artery dissection. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:393-397.

30 Gaul C, Dietrich W, Friedrich I, Sirch J, Erbguth FJ. Neurological symptoms in type A aortic dissections. Stroke. 2007;38:292-297.

31 Wolpert SM, Caplan LR. Current role of cerebral angiography in the diagnosis of cerebrovascular diseases. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1992;159:191-197.

32 Josien E. Extracranial vertebral artery dissection: nine cases. J Neurol. 1992;239:327-330.

33 de Bray JM, Marc G, Pautot V, Vielle B, Pasco A, Lhoste P, et al. Fibromuscular dysplasia may herald symptomatic recurrence of cervical artery dissection. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:448-452.

34 Pico F, Labreuche J, Touboul PJ, Amarenco P. Intracranial arterial dolichoectasia and its relation with atherosclerosis and stroke subtype. Neurology. 2003;61:1736-1742.

35 Pico F, Labreuche J, Cohen A, Touboul PJ, Amarenco P. Intracranial arterial dolichoectasia is associated with enlarged descending thoracic aorta. Neurology. 2004;63:2016-2021.

36 Pico F, Labreuche J, Touboul PJ, Leys D, Amarenco P. Intracranial arterial dolichoectasia and small-vessel disease in stroke patients. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:472-479.

37 Passero SG, Calchetti B, Bartalini S. Intracranial bleeding in patients with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Stroke. 2005;36:1421-1425.

38 Passero S, Filosomi G. Posterior circulation infarcts in patients with vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. Stroke. 1998;29:653-659.

39 Passero S, Rossi S, Giannini F, Nuti D. Brain-stem compression in vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia. A multimodal electrophysiological study. Clin Neurophysiol. 2001;112:1531-1539.

40 Ince B, Petty GW, Brown RDJr, Chu CP, Sicks JD, Whisnant JP. Dolichoectasia of the intracranial arteries in patients with first ischemic stroke: a population-based study. Neurology. 1998;50:1694-1698.

41 Pico F, Labreuche J, Seilhean D, Duyckaerts C, Hauw JJ, Amarenco P. Association of small-vessel disease with dilatative arteriopathy of the brain: neuropathologic evidence. Stroke. 2007;38:1197-1202.

42 Wakai K, Tamakoshi A, Ikezaki K, Fukui M, Kawamura T, Aoki R, et al. Epidemiological features of moyamoya disease in Japan: findings from a nationwide survey. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1997;99(2 Suppl):S1-S5.

43 Fukui M. Current state of study on moyamoya disease in Japan. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:138-143.

44 Yilmaz EY, Pritz MB, Bruno A, Lopez-Yunez A, Biller J. Moyamoya: Indiana University Medical Center experience. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1274-1278.

45 Bruno A, Adams HPJr, Biller J, Rezai K, Cornell S, Aschenbrener CA. Cerebral infarction due to moyamoya disease in young adults. Stroke. 1988;19:826-833.

46 Chiu D, Shedden P, Bratina P, Grotta JC. Clinical features of moyamoya disease in the United States. Stroke. 1998;29:1347-1351.

47 Hallemeier CL, Rich KM, Grubb RLJr, Chicoine MR, Moran CJ, Cross DTIII, et al. Clinical features and outcome in North American adults with moyamoya phenomenon. Stroke. 2006;37:1490-1496.

48 Cloft HJ, Kallmes DF, Snider R, Jensen ME. Idiopathic supraclinoid and internal carotid bifurcation steno-occlusive disease in young American adults. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:772-776.

49 Ueki K, Meyer FB, Mellinger JF. Moyamoya disease: the disorder and surgical treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 1994;69:749-757.

50 Cerrato P, Grasso M, Lentini A, Destefanis E, Bosco G, Caprioli M, et al. Atherosclerotic adult Moya-Moya disease in a patient with hyperhomocysteinaemia. Neurol Sci. 2007;28:45-47.

51 Ullrich NJ, Robertson R, Kinnamon DD, Scott RM, Kieran MW, Turner CD, et al. Moyamoya following cranial irradiation for primary brain tumors in children. Neurology. 2007;68:932-938.

52 Czartoski T, Hallam D, Lacy JM, Chun MR, Becker K. Postinfectious vasculopathy with evolution to moyamoya syndrome. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2005;76:256-259.

53 Storen EC, Wijdicks EF, Crum BA, Schultz G. Moyamoya-like vasculopathy from cocaine dependency. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:1008-1010.

54 Narayan P, Workman MJ, Barrow DL. Surgical treatment of a lenticulostriate artery aneurysm. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:340-342.

55 Tournier-Lasserve E, Joutel A, Melki J, Weissenbach J, Lathrop GM, Chabriat H, et al. Cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy maps to chromosome 19q12. Nat Genet. 1993;3:256-259.

56 Yousry TA, Seelos K, Mayer M, Bruning R, Uttner I, Dichgans M, et al. Characteristic MR lesion pattern and correlation of T1 and T2 lesion volume with neurologic and neuropsychological findings in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1999;20:91-100.

57 Singhal S, Rich P, Markus HS. The spatial distribution of MR imaging abnormalities in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy and their relationship to age and clinical features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2005;26:2481-2487.

58 O’Sullivan M, Jarosz JM, Martin RJ, Deasy N, Powell JF, Markus HS. MRI hyperintensities of the temporal lobe and external capsule in patients with CADASIL. Neurology. 2001;56:628-634.

59 Choi JC, Kang SY, Kang JH, Park JK. Intracerebral hemorrhages in CADASIL. Neurology. 2006;67:2042-2044.

60 Viswanathan A, Guichard JP, Gschwendtner A, Buffon F, Cumurcuic R, Boutron C, et al. Blood pressure and haemoglobin A1c are associated with microhaemorrhage in CADASIL: a two-centre cohort study. Brain. 2006;129(Pt 9):2375-2383.

61 Malandrini A, Gaudiano C, Gambelli S, Berti G, Serni G, Bianchi S, et al. Diagnostic value of ultrastructural skin biopsy studies in CADASIL. Neurology. 2007;68:1430-1432.

62 Iizuka T, Sakai F, Kan S, Suzuki N. Slowly progressive spread of the stroke-like lesions in MELAS. Neurology. 2003;61:1238-1244.

63 Oppenheim C, Galanaud D, Samson Y, Sahel M, Dormont D, Wechsler B, et al. Can diffusion weighted magnetic resonance imaging help differentiate stroke from stroke-like events in MELAS? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:248-250.

64 Iizuka T, Sakai F, Kan S, Suzuki N. Slowly progressive spread of the stroke-like lesions in MELAS. Neurology. 2003;61:1238-1244.

65 Takasu M, Kajima T, Ito K, Kato Y, Sakura N. A case of MELAS: hyperperfused lesions detected by non-invasive perfusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2002;1:50-53.

66 Castillo M, Kwock L, Green C. MELAS syndrome: imaging and proton MR spectroscopic findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1995;16:233-239.

67 Abe K, Yoshimura H, Tanaka H, Fujita N, Hikita T, Sakoda S. Comparison of conventional and diffusion-weighted MRI and proton MR spectroscopy in patients with mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, and stroke-like events. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:113-117.

68 Iizuka T, Sakai F, Suzuki N, Hata T, Tsukahara S, Fukuda M, et al. Neuronal hyperexcitability in stroke-like episodes of MELAS syndrome. Neurology. 2002;59:816-824.

69 Iizuka T, Sakai F, Ide T, Miyakawa S, Sato M, Yoshii S. Regional cerebral blood flow and cerebrovascular reactivity during chronic stage of stroke-like episodes in MELAS—implication of neurovascular cellular mechanism. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257(1-2):126-138.

70 Call GK, Fleming MC, Sealfon S, Levine H, Kistler JP, Fisher CM. Reversible cerebral segmental vasoconstriction. Stroke. 1988;19:1159-1170.

71 Ducros A, Boukobza M, Porcher R, Sarov M, Valade D, Bousser MG. The clinical and radiological spectrum of reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndrome. A prospective series of 67 patients. Brain. 2007;130:3091-3101.

72 Calabrese LH, Dodick DW, Schwedt TJ, Singhal AB. Narrative review: reversible cerebral vasoconstriction syndromes. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:34-44.

73 Tardy B, Page Y, Convers P, Mismetti P, Barral F, Bertrand JC. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: MR findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1993;14:489-490.

74 Scheid R, Hegenbart U, Ballaschke O, Von Cramon DY. Major stroke in thrombotic-thrombocytopenic purpura (Moschcowitz syndrome). Cerebrovasc Dis. 2004;18:83-85.

75 Kondo K, Yamawaki T, Nagatsuka K, Miyashita K, Naritomi H. Reversible stenosis of major cerebral arteries demonstrated by MRA in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Neurol. 2003;250:995-997.

76 Bakshi R, Shaikh ZA, Bates VE, Kinkel PR. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: brain CT and MRI findings in 12 patients. Neurology. 1999;52:1285-1288.

77 Park SA, Lee TK, Sung KB, Park SK. Extensive brain stem lesions in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: repeat magnetic resonance findings. J Neuroimaging. 2005;15:79-81.

78 Kay AC, Solberg LAJr, Nichols DA, Petitt RM. Prognostic significance of computed tomography of the brain in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Mayo Clin Proc. 1991;66:602-607.

79 Gruber O, Wittig L, Wiggins CJ, Von Cramon DY. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura: MRI demonstration of persistent small cerebral infarcts after clinical recovery. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:616-618.

80 Rabinstein AA. Stroke in HIV-infected patients: a clinical perspective. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2003;15:37-44.

81 MacLaren K, Gillespie J, Shrestha S, Neary D, Ballardie FW. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: emerging variants. QJM. 2005;98:643-654.

82 Campi A, Benndorf G, Filippi M, Reganati P, Martinelli V, Terreni MR. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system: serial MRI of brain and spinal cord. Neuroradiology. 2001;43:599-607.

83 Salvarani C, Brown RDJr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Weigand SD, Miller DV, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis: analysis of 101 patients. Ann Neurol. 2007;62:442-451.

84 Salvarani C, Brown RDJr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston JIII, Meschia JF, et al. Primary CNS vasculitis with spinal cord involvement. Neurology. 2008;70:2394-2400.

85 Hajj-Ali RA, Furlan A, Abou-Chebel A, Calabrese LH. Benign angiopathy of the central nervous system: cohort of 16 patients with clinical course and long-term followup. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;47:662-669.

86 Alhalabi M, Moore PM. Serial angiography in isolated angiitis of the central nervous system. Neurology. 1994;44:1221-1226.

87 Kadkhodayan Y, Alreshaid A, Moran CJ, Cross DTIII, Powers WJ, Derdeyn CP. Primary angiitis of the central nervous system at conventional angiography. Radiology. 2004;233:878-882.

88 Salvarani C, Brown RDJr, Calamia KT, Christianson TJ, Huston JIII, Meschia JF, et al. Primary central nervous system vasculitis with prominent leptomeningeal enhancement: a subset with a benign outcome. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:595-603.

89 Alreshaid AA, Powers WJ. Prognosis of patients with suspected primary CNS angiitis and negative brain biopsy. Neurology. 2003;61:831-833.

90 Caselli RJ, Hunder GG, Whisnant JP. Neurologic disease in biopsy-proven giant cell (temporal) arteritis. Neurology. 1988;38:352-359.

91 Goodman BWJr. Temporal arteritis. Am J Med. 1979;67:839-852.

92 Taylor-Gjevre R, Vo M, Shukla D, Resch L. Temporal artery biopsy for giant cell arteritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32:1279-1282.

93 Save-Soderbergh J, Malmvall BE, Andersson R, Bengtsson BA. Giant cell arteritis as a cause of death. Report of nine cases. JAMA. 1986;255:493-496.

94 Gibb WR, Urry PA, Lees AJ. Giant cell arteritis with spinal cord infarction and basilar artery thrombosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:945-948.

95 Mclean CA, Gonzales MF, Dowling JP. Systemic giant cell arteritis and cerebellar infarction. Stroke. 1993;24:899-902.

96 Schmidt WA, Kraft HE, Vorpahl K, Volker L, Gromnica-Ihle EJ. Color duplex ultrasonography in the diagnosis of temporal arteritis. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1336-1342.

97 Karassa FB, Matsagas MI, Schmidt WA, Ioannidis JP. Meta-analysis: test performance of ultrasonography for giant-cell arteritis. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:359-369.

98 Garcia-Martinez A, Hernandez-Rodriguez J, Arguis P, Paredes P, Segarra M, Lozano E, et al. Development of aortic aneurysm/dilatation during the followup of patients with giant cell arteritis: a cross-sectional screening of fifty-four prospectively followed patients. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:422-430.

99 Susac JO, Hardman JM, Selhorst JB. Microangiopathy of the brain and retina. Neurology. 1979;29:313-316.

100 Susac JO. Susac’s syndrome: the triad of microangiopathy of the brain and retina with hearing loss in young women. Neurology. 1994;44:591-593.

101 Bogousslavsky J, Gaio JM, Caplan LR, Regli F, Hommel M, Hedges TRIII, et al. Encephalopathy, deafness and blindness in young women: a distinct retinocochleocerebral arteriolopathy? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:43-46.

102 Susac JO, Egan RA, Rennebohm RM, Lubow M. Susac’s syndrome: 1975–2005 microangiopathy/autoimmune endotheliopathy. J Neurol Sci. 2007;257:270-272.

103 Aubart-Cohen F, Klein I, Alexandra JF, Bodaghi B, Doan S, Fardeau C, et al. Long-term outcome in Susac syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:93-102.

104 Susac JO, Murtagh FR, Egan RA, Berger JR, Bakshi R, Lincoff N, et al. MRI findings in Susac’s syndrome. Neurology. 2003;61:1783-1787.

105 Leiguarda R, Berthier M, Starkstein S, Nogues M, Lylyk P. Ischemic infarction in 25 children with tuberculous meningitis. Stroke. 1988;19:20-204.

106 Hsieh FY, Chia LG, Shen WC. Locations of cerebral infarctions in tuberculous meningitis. Neuroradiology. 1992;34:197-199.

107 Belorgey L, Lalani I, Zakaria A. Ischemic stroke in the setting of tuberculous meningitis. J Neuroimaging. 2006;16:364-366.

108 Uesugi T, Takizawa S, Morita Y, Takahashi H, Takagi S. Hemorrhagic infarction in tuberculous meningitis. Intern Med. 2006;45:1193-1194.

109 Losurdo G, Giacchino R, Castagnola E, Gattorno M, Costabel S, Rossi A, et al. Cerebrovascular disease and varicella in children. Brain Dev. 2006;28:366-370.

110 Berkefeld J, Enzensberger W, Lanfermann H. MRI in human immunodeficiency virus-associated cerebral vasculitis. Neuroradiology. 2000;42:526-528.

111 Ortiz G, Koch S, Romano JG, Forteza AM, Rabinstein AA. Mechanisms of ischemic stroke in HIV-infected patients. Neurology. 2007;68:1257-1261.

112 van de BD, Patel R, Campeau NG, Badley A, Parisi JE, Rabinstein AA, et al. Insidious sinusitis leading to catastrophic cerebral aspergillosis in transplant recipients. Neurology. 2008;70:2411-2413.

113 Walsh TJ, Hier DB, Caplan LR. Aspergillosis of the central nervous system: clinicopathological analysis of 17 patients. Ann Neurol. 1985;18:574-582.

114 Connor MD, Lammie GA, Bell JE, Warlow CP, Simmonds P, Brettle RD. Cerebral infarction in adult AIDS patients: observations from the Edinburgh HIV Autopsy Cohort. Stroke. 2000;31:2117-2126.

115 Brilla R, Nabavi DG, Schulte-Altedorneburg G, Kemeny V, Reichelt D, Evers S, et al. Cerebral vasculopathy in HIV infection revealed by transcranial Doppler: a pilot study. Stroke. 1999;30:811-813.

116 Nogueras C, Sala M, Sasal M, Vinas J, Garcia N, Bella MR, et al. Recurrent stroke as a manifestation of primary angiitis of the central nervous system in a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Neurol. 2002;59:468-473.

117 Dubrovsky T, Curless R, Scott G, Chaneles M, Post MJ, Altman N, et al. Cerebral aneurysmal arteriopathy in childhood AIDS. Neurology. 1998;51:560-565.

118 Philippet P, Blanche S, Sebag G, Rodesch G, Griscelli C, Tardieu M. Stroke and cerebral infarcts in children infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1994;148:965-970.

119 Patsalides AD, Wood LV, Atac GK, Sandifer E, Butman JA, Patronas NJ. Cerebrovascular disease in HIV-infected pediatric patients: neuroimaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:999-1003.

120 Kabus D, Greco MA. Arteriopathy in children with AIDS: microscopic changes in the vasa vasorum with gross irregularities of the aortic intima. Pediatr Pathol. 1991;11:793-795.

121 Persidsky Y, Stins M, Way D, Witte MH, Weinand M, Kim KS, et al. A model for monocyte migration through the blood-brain barrier during HIV-1 encephalitis. J Immunol. 1997;158:3499-3510.

122 Dubec JJ, Munk PL, Tsang V, Lee MJ, Janzen DL, Buckley J, et al. Carotid artery stenosis in patients who have undergone radiation therapy for head and neck malignancy. Br J Radiol. 1998;71:872-875.

123 Cheng SW, Ting AC, Ho P, Wu LL. Accelerated progression of carotid stenosis in patients with previous external neck irradiation. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:409-415.

124 Bitzer M, Topka H. Progressive cerebral occlusive disease after radiation therapy. Stroke. 1995;26:131-136.

125 Murros KE, Toole JF. The effect of radiation on carotid arteries. A review article. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:449-455.

126 Painter MJ, Chutorian AM, Hilal SK. Cerebrovasculopathy following irradiation in childhood. Neurology. 1975;25:189-194.

127 Qureshi AI, Alexandrov AV, Tegeler CH, Hobson RW, Dennis BJ, Hopkins LN. Guidelines for screening of extracranial carotid artery disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the multidisciplinary practice guidelines committee of the American Society of Neuroimaging; cosponsored by the Society of Vascular and Interventional Neurology. J Neuroimaging. 2007;17:19-47.

128 Mozes G, Sullivan TM, Torres-Russotto DR, Bower TC, Hoskin TL, Sampaio SM, et al. Carotid endarterectomy in SAPPHIRE-eligible high-risk patients: implications for selecting patients for carotid angioplasty and stenting. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:958-965.

129 Yadav JS, Wholey MH, Kuntz RE, Fayad P, Katzen BT, Mishkel GJ, et al. Protected carotid-artery stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1493-1501.

130 Protack CD, Bakken AM, Saad WA, Illig KA, Waldman DL, Davies MG. Radiation arteritis: a contraindication to carotid stenting? J Vasc Surg. 2007;45:110-117.

131 Aggarwal SK, Williams V, Levine SR, Cassin BJ, Garcia JH. Cocaine-associated intracranial hemorrhage: absence of vasculitis in 14 cases. Neurology. 1996;46:1741-1743.

132 Krendel DA, Ditter SM, Frankel MR, Ross WK. Biopsy-proven cerebral vasculitis associated with cocaine abuse. Neurology. 1990;40:1092-1094.

133 Brust JC. Vasculitis owing to substance abuse. Neurol Clin. 1997;15:945-957.

134 Martin K, Rogers T, Kavanaugh A. Central nervous system angiopathy associated with cocaine abuse. J Rheumatol. 1995;22:780-782.

135 Fredericks RK, Lefkowitz DS, Challa VR, Troost BT. Cerebral vasculitis associated with cocaine abuse. Stroke. 1991;22:1437-1439.

136 Kaye BR, Fainstat M. Cerebral vasculitis associated with cocaine abuse. JAMA. 1987;258:2104-2106.

137 Herning RI, Better W, Nelson R, Gorelick D, Cadet JL. The regulation of cerebral blood flow during intravenous cocaine administration in cocaine abusers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;890:489-494.

138 Kaufman MJ, Levin JM, Ross MH, Lange N, Rose SL, Kukes TJ, et al. Cocaine-induced cerebral vasoconstriction detected in humans with magnetic resonance angiography. JAMA. 1998;279:376-380.

139 Ohene-Frempong K, Weiner SJ, Sleeper LA, Miller ST, Embury S, Moohr JW, et al. Cerebrovascular accidents in sickle cell disease: rates and risk factors. Blood. 1998;91:288-294.

140 Dobson SR, Holden KR, Nietert PJ, Cure JK, Laver JH, Disco D, et al. Moyamoya syndrome in childhood sickle cell disease: a predictive factor for recurrent cerebrovascular events. Blood. 2002;99:3144-3150.

141 Adams RJ, Nichols FT, McKie V, McKie K, Milner P, Gammal TE. Cerebral infarction in sickle cell anemia: mechanism based on CT and MRI. Neurology. 1988;38:1012-1017.

142 Adams RJ. Stroke prevention and treatment in sickle cell disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:565-568.

143 Adams R, McKie V, Nichols F, Carl E, Zhang DL, McKie K, et al. The use of transcranial ultrasonography to predict stroke in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:605-610.

144 Adams RJ, McKie VC, Hsu L, Files B, Vichinsky E, Pegelow C, et al. Prevention of a first stroke by transfusions in children with sickle cell anemia and abnormal results on transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:5-11.

145 Wang WC. The pathophysiology, prevention, and treatment of stroke in sickle cell disease. Curr Opin Hematol. 2007;14:191-197.

146 Adams RJ, Brambilla D. Discontinuing prophylactic transfusions used to prevent stroke in sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2769-2778.

147 Hankins JS, Fortner GL, McCarville MB, Smeltzer MP, Wang WC, Li CS, et al. The natural history of conditional transcranial Doppler flow velocities in children with sickle cell anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2008;142:94-99.