Ultraviolet radiation and the skin

An interaction between skin and sunlight is inescapable. The potential for harm depends on the type and length of exposure. Photoageing is a growing problem, because of an increasingly aged population and a rise in the average individual exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

The electromagnetic radiation spectrum

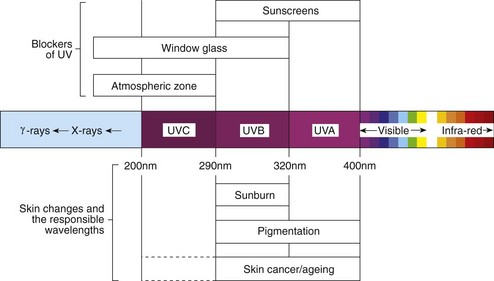

The sun’s emission of electromagnetic radiation ranges from low-wavelength ionizing cosmic, gamma and X-rays to the non-ionizing UV, visible and infrared higher wavelengths (Fig. 1). The ozone layer absorbs UVC, but UVA and smaller amounts of UVB reach ground level. UV radiation is maximal in the middle of the day (11.00–15.00 h) and is increased by reflection from snow, water and sand. UVA penetrates the epidermis to reach the dermis. UVB is mostly absorbed by the stratum corneum – only 10% reaches the dermis. Most window glass absorbs UV less than 320 nm in wavelength. Artificial UV sources emit in the UVB or UVA spectrum. Sunbeds largely emit UVA.

Effects of light on normal skin

Physiological

UVB promotes the synthesis of vitamin D3 from its precursors in the skin, and UVA and UVB stimulate immediate pigmentation (due to photo-oxidation of melanin precursors), melanogenesis and epidermal thickening as a protective measure against UV damage (p. 7).

Sunburn

If enough UVB is given, erythema always results. The threshold dose of UVB – the minimal erythema dose (MED) – is a guide to an individual’s susceptibility. Excessive UVB exposure results in tingling of the skin, followed 2–12 h later by erythema. The redness is maximal at 24 h and fades over the next 2 or 3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation. Severe sunburn causes oedema, pain, blistering and systemic upset. The early use of topical steroids may help sunburn; otherwise, a soothing shake lotion (e.g. calamine lotion) is applied. Individuals may be skin typed by their likelihood of burning in the sun (Table 1). Prevention is better than cure, and ‘celts’ with a fair ‘type 1’ skin should not sunbathe and must use a high protection factor sunblock cream on exposed sites (p. 108). Some evidence suggests the sun avoidance message may have gone too far in that it could be causing white populations to become vitamin D deficient.

| Skin type | Reaction to sun exposure |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | Always burns, never tans |

| Type 2 | Always burns, sometimes tans |

| Type 3 | Sometimes burns, always tans |

| Type 4 | Never burns, always tans |

| Type 5 | Brown skin (e.g. Asian caucasoid) |

| Type 6 | Black skin (e.g. black African) |

Phototherapy and photochemotherapy

Natural sunlight helps certain skin diseases (p. 46), and both UVB and UVA are extensively used therapeutically. UVA alone has little effect and is combined with photosensitizing psoralens given systemically or topically.

Ultraviolet B

When used to treat psoriasis, UVB may be combined with a topical preparation such as a vitamin D analogue (p. 30), tar or dithranol, or with oral acitretin.

Photochemotherapy (PUVA)

In psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy, 8-methoxypsoralen, taken orally 2 h before UVA (320–400 nm) exposure (Fig. 2), is photoactivated. This causes cross-linkage in DNA, inhibits cell division and suppresses cell-mediated immunity. PUVA is usually given for psoriasis or mycosis fungoides, and sometimes for atopic eczema, polymorphic light eruption (p. 46) or vitiligo (p. 74). The initial dose of UVA is determined by the minimum toxic dose (the MED for PUVA) or skin type, and is increased according to a schedule. PUVA is given two or three times a week and leads to clearance of psoriasis (with tanning) in 15–25 treatments. Maintenance PUVA is not recommended. PUVA can be combined with acitretin (‘Re-PUVA’) but not methotrexate.

Photoageing

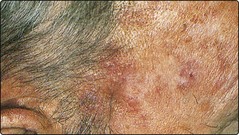

Photoageing describes the skin changes resulting from chronic sun exposure. Photoaged skin is coarse, wrinkled, pale-yellow in colour, telangiectatic, irregularly pigmented, prone to purpura and subject to benign and malignant neoplasms (Fig. 3). Some of these changes resemble those of intrinsic ageing, but the two are not identical, as may be judged by comparing, in an elderly patient, the sun-exposed face with the sun-protected buttock. The features of photoageing are usually more striking, particularly the development of premalignant and malignant tumours. Some rare conditions, e.g. xeroderma pigmentosum (p. 92), predispose to photoageing.

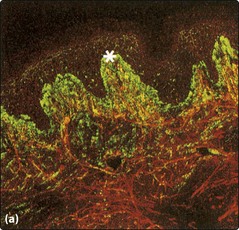

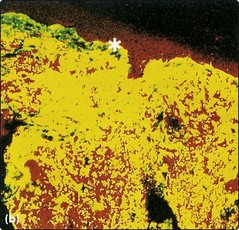

Histologically, the photoaged dermis shows tangled clumps of elastin with proliferation of glycosaminoglycans (Fig. 4). The epidermis is variable in thickness, with areas of atrophy and hypertrophy and a variation in the degree of pigmentation. In vitro, keratinocytes and fibroblasts from sun-exposed sites have a reduced proliferative ability compared with cells from sun-protected sites. The specific clinical changes of photoageing are discussed on page 118.

Management of photoageing

Prevention is the most effective treatment and is particularly important for those with a fair (type 1 or 2) skin. Avoidance of prolonged, direct sun exposure by wearing long-sleeved shirts and a wide-brimmed hat is useful, and sunscreens (p. 108) are applied to sites that are likely to receive some sun, such as the face or hands. The use of tretinoin or alpha hydroxy acids, in cream formulations, has been shown partially to reverse the clinical and histological changes of photoageing. Chemical peels and laser resurfacing are also used.

UV and the skin

UVB radiation is mostly absorbed by the epidermis, but UVA can penetrate to the dermis. UVB promotes vitamin D synthesis. UVA and UVB stimulate melanogenesis and epidermal thickening.

UVB radiation is mostly absorbed by the epidermis, but UVA can penetrate to the dermis. UVB promotes vitamin D synthesis. UVA and UVB stimulate melanogenesis and epidermal thickening.

Minimal erythema dose is the threshold amount of UVB to cause erythema.

Minimal erythema dose is the threshold amount of UVB to cause erythema.

Sunburn is maximal at 24 h and fades at 2–3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation of the skin.

Sunburn is maximal at 24 h and fades at 2–3 days to leave desquamation and pigmentation of the skin.

Sunbeds emit UVA and will induce a tan in those with type 3 or 4 skin. Side-effects are common.

Sunbeds emit UVA and will induce a tan in those with type 3 or 4 skin. Side-effects are common.

Photoageing describes coarse, wrinkled, yellowed skin, prone to tumours, resulting from excess sun exposure.

Photoageing describes coarse, wrinkled, yellowed skin, prone to tumours, resulting from excess sun exposure.

UVB therapy, now mostly narrow-band TL01, is mainly used in psoriasis; a course of 10–30 treatments is usual.

UVB therapy, now mostly narrow-band TL01, is mainly used in psoriasis; a course of 10–30 treatments is usual.

PUVA has been a common treatment for psoriasis; used less now. Skin cancer is one potential long-term sequela.

PUVA has been a common treatment for psoriasis; used less now. Skin cancer is one potential long-term sequela.

Treatment of photoageing: prevention is best, but tretinoin cream can reverse some of the changes.

Treatment of photoageing: prevention is best, but tretinoin cream can reverse some of the changes.