Chapter 18 Tympanoplasty—Staging and Use of Plastic

POSTOPERATIVE COLLAPSE OF TYMPANIC MEMBRANE

Retraction and collapse of the tympanic membrane is a well-recognized postoperative problem. Many authors blame the collapse on continued poor eustachian tube function.1 Others blame the collapse on fibrous adhesions between the denuded middle ear surfaces and the tympanic membrane graft (see later). The introduction of a barrier material, such as silicone elastomer (Silastic) sheeting, between these two raw surfaces prevents the formation of fibrous adhesions, with subsequent retraction and collapse of the tympanic membrane. This alternative explanation is supported by observations of healing after staging. In a review of 400 planned two-stage tympanoplasty operations, 89% of patients achieved an aerated middle ear, 5% required the placement of a ventilation tube, and the remainder developed collapse of the middle ear space.2 These results would indicate that continued eustachian tube dysfunction is an uncommon cause for postoperative tympanic membrane retraction.

INDICATIONS FOR STAGING

There are two reasons for staging the operation in tympanoplasty: (1) obtaining a permanently disease-free ear and (2) obtaining permanent restoration of hearing.3,4 Whether one finds any indication for staging depends on how vigorously a good functional result is pursued in badly diseased ears.

Residual Cholesteatoma Factor

The surgeon may have torn the matrix when removing it from the tympanic recess and may be uncertain of complete removal, which presents a considerable problem under the pyramidal process, an area hidden from view regardless of the technique of surgery, whether it is an open or closed cavity technique. Removal of the pyramidal process with a diamond burr may or may not resolve the problem. One third of patients with middle ear cholesteatoma at the first operation have residual disease at the second stage.2

PLASTIC IN THE MIDDLE EAR

The most common middle ear indication for staging the operation is a mucous membrane problem. To avoid confusion, the following discussion is limited to that problem. The techniques are the same when there are other indications.6

Mucous Membrane Indications

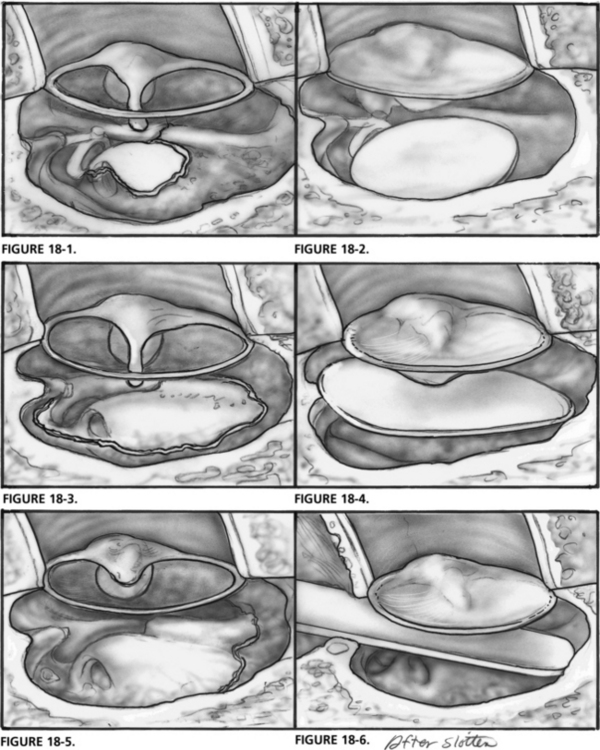

When the mucous membrane problem is limited, there is no need for staging (Fig. 18-1). Adhesions form between denuded bone of the middle ear and the tympanic membrane graft, but usually do not pose a long-term problem. Nonetheless, Gelfilm is frequently placed over the denuded areas to prevent adhesions (Fig. 18-2). Alternatively, one may use thin silicone sheeting, if desired. The silicone sheeting may be left in place indefinitely.

In more diseased ears, one may find that normal mucosa remains only in the tubotympanum, facial recess, and epitympanum (Fig. 18-3). Reconstruction of this ear without regard to the mucous membrane problem usually results in a fibrosed middle ear.

When thin silicone sheeting was used in such cases in the early 1960s, the results were frequently disappointing. The silicone sheeting was rolled up or deformed by advancing fibrous tissue. If the silicone sheeting contacted the tympanic membrane, extrusion often occurred. To obtain the best hearing results in such cases, it was necessary to perform the reconstruction in two stages. At the initial operation, the tympanic membrane was grafted over a piece of thick silicone sheeting that filled the middle ear (Fig. 18-4). Six months later, the thick silicone sheeting was removed, and a suitable prosthesis was inserted.

In badly infected ears, there may be no mucosa remaining in the middle ear cleft except for the tubotympanum (Fig. 18-5). Some physicians believe that nothing can be done to reconstruct such an ear; radical mastoidectomy has been advised. Ears of this type can be reconstructed by staging the tympanoplasty, as long as some mucosa remains in the tubotympanum, and the plastic sheeting can reach the area to prevent eustachian tube closure.

In cases of extensive or total mucous membrane destruction, it may be wise to perform an intact canal wall mastoidectomy even though there may not be other indications for a mastoid exploration. The mastoid is opened into the middle ear through the facial recess for insertion of a sheet of Supramid or thick silicone sheeting (Fig. 18-6). This process ensures that the plastic would not roll up—hence, no fibrous tissue. During revision, the plastic is removed, and a suitable prosthesis may be placed between the stapes capitulum or footplate and the mobile tympanic membrane in a well-healed normal middle ear.

CONTROVERSY

There is considerable difference of opinion among experienced otologists in regard to staging the operation.5 The major difference occurs over more diseased ears, usually with cholesteatoma, and is related not to the management of the mastoid (canal wall up or canal wall down), but instead to the surgeon’s philosophy.7 Staging proponents believe that the great divergence of opinion on staging that one encounters is related to two factors. How hard does the individual pursue a good functional result in the most severely diseased ear? What does one accept as a satisfactory functional result? In an ear with no remaining mucosa except in the tubotympanum, it is our experience that unless the operation is staged, one cannot usually obtain a satisfactory functional result.

1. Sheehy J.L. Testing eustachian tube function. Ann Otol. 1981;90:562-564.

2. Rambo J.H.T. Use of paraffin to create a middle ear space in musculoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:612-619.

3. Tabb H.G. Surgical management of chronic ear disease with special reference to staged surgery. Laryngoscope. 1963;73:363-383.

4. House H.P. Polyethylene in middle ear surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1960;71:926-931.

5. Austin D.F. Types and indications of staging. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1969;89:235-242.

6. Smyth G.D.L. Staged tympanoplasty. J Laryngol. 1970;84:757-764.

7. Sheehy J.L. Plastic sheeting in tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:1144-1159.

8. Sheehy J.L., Crabtree J.A. Tympanoplasty: Staging the operation. Laryngoscope. 1973;83:1594-1621.

9. Sheehy J.L., Shelton C. Tympanoplasty: To stage or not to stage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:399-407.

10. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E. Surgery of chronic otitis media. In: English G.M., editor. Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott, 1994.

11. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E. Surgery of Chronic Ear Disease: What We Do and Why We Do It. Instructional Courses. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1993. Vol. 6

∗ Editorial Note: James Sheehy was a skillful surgeon and a master teacher. For many of us, his name is synonymous with surgical management of chronic otitis media. Jim was the sole author of this chapter in our first two editions. It is difficult to improve on a chapter that is done so well. The current chapter represents an update of the chapter in the previous edition with minor revisions.