Chapter 9 Tympanoplasty—Outer Surface Grafting Technique

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

HISTORICAL ASPECTS

Systematic reconstruction of the tympanic membrane, the sine qua non of the modern era of reconstructive ear surgery, had its beginning with reports by Wullstein1 and Zollner.2 Split-thickness or full-thickness skin was placed over the de-epithelialized tympanic membrane remnant. The initial results were very encouraging, but graft eczema, inflammation, and perforation were common.

As a result of these experiences, most surgeons had begun changing to undersurface (underlay) connective tissue grafts by the late 1950s (see Chapters 11 and 12). The House Clinic physicians continued using an onlay technique, but changed to “canal skin,”3,4 which actually was periosteum graft covered by canal skin. This change was made in 1958, and resulted in an immediate improvement in results. Draining ears and total perforations continued to have a failure rate reaching 40%.

In 1961, Storrs5 published the results of a small series of cases in which temporalis fascia had been used as an outer surface graft. Changing to this technique resulted in a dramatic improvement in results over the next 3 years: greater than 90% graft take.6–8

PATIENT SELECTION AND EVALUATION

Let us assume, for purposes of this chapter, that the patient has a dry central perforation. The ear may drain briefly with upper respiratory infections or if water is allowed to get into the ear. This discharge responds promptly to local medication. The preoperative treatment of the draining ear is discussed in depth in Chapter 16. When one is dealing with a dry central perforation, or inactive disease, surgery is elective, and the patient (or family) should be so informed. Assuming that the problem is unilateral, with only a mild hearing impairment, the only indication for surgery is to avoid further episodes of otorrhea.

When contemplating tympanoplasty, the House Clinic physicians do not usually test to determine the status of the eustachian tube.9 The philosophy has been that tubal malfunction per se is not a contraindication to tympanoplasty, but that the operation would not be successful unless tubal function is re-established. Many patients showing no tubal function by various available tests used in the past have been operated on to eliminate a chronic drainage problem. When the ear heals, the drum is usually mobile. Re-exploration in some of these patients has shown normal mucosa in the tubotympanum, where before surgery the mucosa was of a very poor quality. It would seem that the surgery, in eliminating infection and sealing the ear, is in itself the best treatment for the obstructed tube.

PATIENT COUNSELING

What is the outlook with surgery, and what are the risks and complications? A surgeon must relate his or her own experience. House Clinic physicians explain that the likelihood of obtaining a permanently healed, dry ear, which may be treated normally, is better than 90%. “The only complication that happens with any degree of regularity, and is serious, is a total loss of hearing in the operated ear. That likelihood is no more than 1%. All of the other things listed here are either very remote or are temporary.” (“Listed here” refers to the Risk and Complications section of a patient Discussion Booklet. The Risk and Complications Sheet is given to the patient at the time the surgery is scheduled, which allows the patient to review the sheet leisurely. Appendix 1 is the Risk and Complications Sheet.)

PREPARATION IN THE OPERATING ROOM

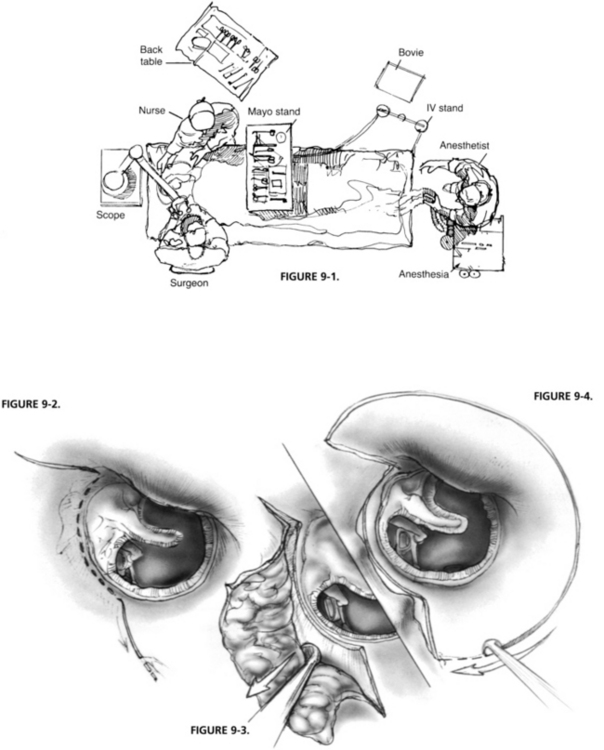

Arrangement and Instrumentation

Particular attention should be paid to operating room arrangement (Fig. 9-1). The anesthesiologist is at the patient’s feet, far removed from the operating field, and the scrub nurse is directly across from the surgeon, where the nurse may be of the most assistance. The same arrangement, minus the anesthesiologist, is used for procedures done with the patient under local anesthesia.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

The lateral surface grafting technique involves eight steps: (1) transmeatal canal incisions, and elevations of the vascular strip; (2) postauricular exposure, and removal and dehydration of the temporalis fascia; (3) removal of canal skin; (4) enlargement of the ear canal by removal of the anterior (and inferior) canal bulge; (5) de-epithelialization of the tympanic membrane remnant; (6) placement of the rehydrated fascia on the outer surface of the remnant, but under the manubrium; (7) replacement of canal skin; and (8) closure of the postauricular incision and replacement of the vascular strip transmeatally.10

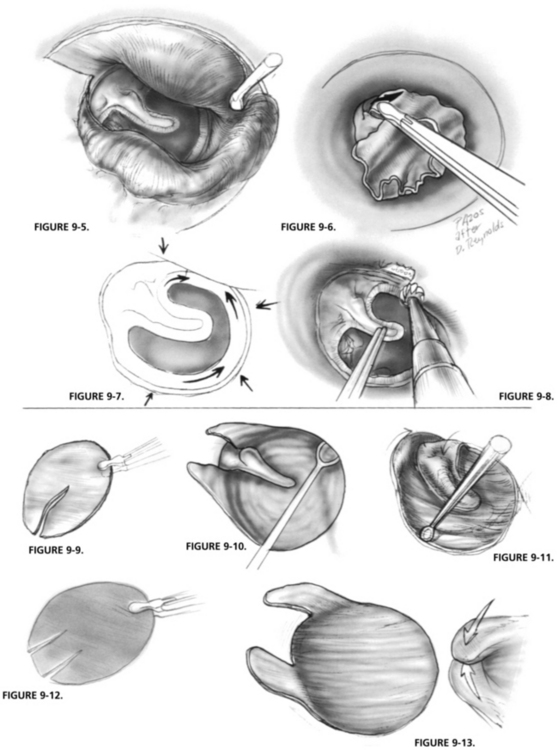

Transmeatal Incisions

Incisions are made along the tympanomastoid and tympanosquamous suture lines, demarcating the vascular strip with a No. 1 (sickle) knife (Fig. 9-2). The vascular strip is the area of the canal skin that covers the superior and posterior portions of the ear canal between these two suture lines. It is easily demarcated from the skin of the remainder of the ear canal because of its thickness, and the fact that it balloons up when local anesthesia is injected into the area. The vascular strip is elevated from the bone, from within outward using a round knife (Fig. 9-3).

A semilunar incision is made in the outer third of the ear canal, using a Beaver knife with a No. 64 blade, connecting the two incisions already made along the border of the vascular strip (Fig. 9-4). The knife blade is angled toward the bone to thin the 1 or 2 mm section of the membranous canal included.

Removal of the Canal Skin

The periosteum and canal skin are elevated from the bone as far as the annular ligament (Fig. 9-5). Care should be taken not to elevate the ligament and the remnant of the middle fibrous layer. The dissection is superficial to the fibrous layer of the remnant in such a way that the remnant is de-epithelialized in continuity with the canal skin, if possible. It is often easier to begin the final removal and de-epithelialization by starting anterosuperiorly, using a cup forceps (Fig. 9-6). Removal of the canal skin and de-epithelialization are continued inferiorly and posteriorly. The periosteum and canal skin are removed from the ear and kept moist in Tis-U-Sol irrigating solution.

In elevating the periosteum and the canal skin, one works perpendicular to the annular ligament and remnant, keeping the instrument on the bone at all times, until the dissection is completed to the level of the remnant. The dissection is continued parallel to the annular ligament to avoid elevating it and the remnant (Fig. 9-7).

Enlargement of the Ear Canal

Through the use of a drill and continuous suction-irrigation, the ear canal is enlarged by removal of the anterior and inferior canal bulges (Fig. 9-8). The importance of this step in the lateral surface grafting technique cannot be overemphasized. Removal of this bone enlarges the field of surgery. The anterior and inferior sulci are thoroughly exposed to allow de-epithelialization and satisfactory graft placement. The acute angle that exists anteriorly is opened, helping to prevent postoperative blunting. There is no area hidden from postoperative observation. Enlarging the ear canal is routine in all lateral surface grafting procedures, and is the main reason for removal of canal skin.

Placement of Fascia

The dehydrated fascia is trimmed to an oval shape measuring approximately 1.3 × 1.5 cm. A slit is cut in the fascia to allow placement under the manubrium (Fig. 9-9). The two cut ends are grasped with the forceps, and the fascia is immersed for a few seconds in Tis-U-Sol irrigating solution to hydrate it.

The fascia is placed over the perforation and immediately slipped under the manubrium (Fig. 9-10). One ensures that the apex of the slit in the fascia comes into contact with the tensor tendon. The fascia is adjusted to the remnant anteriorly and inferiorly, with care being taken that it does not extend onto the bony wall anteriorly, unless there is no remnant at all, then it should extend only for 1 mm at the most. The anterior flap is turned back over the exposed manubrium, resulting in a better appearance of the membrane when healed (Fig. 9-11).

When the malleus is absent, and there is only a small remnant present, it is necessary to insert the fascia in a different way to result in the stabilized graft (Fig. 9-12). The fascia is cut twice, creating a flap that can be tucked under the lateral wall of the epitympanum. The anterosuperior edge of the fascia is swung posteriorly to overlap the upper edge of the graft and secure the seal of the middle ear (Fig. 9-13).

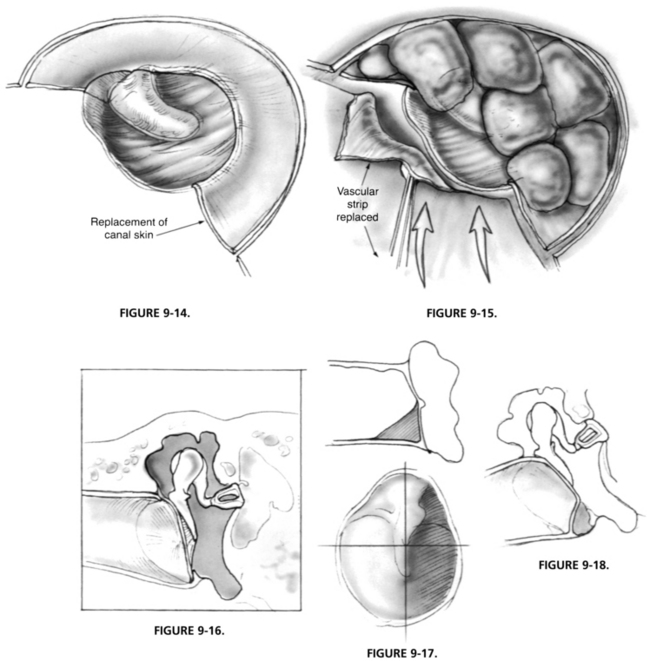

Replacement of Canal Skin

The canal skin is replaced to cover the bone from which it was removed. It is positioned only slightly more medially, allowing it to overlap the fascia by 1 mm (Fig. 9-14), which helps promote rapid epithelialization. Epithelialization is particularly important in preventing blunting in the anterosuperior sulcus. There must be no edges of epithelium turned under, or small epithelial cysts may develop on the surface of the fascia during healing.

Closure and Replacement of the Vascular Strip

The retractors are released, and the vascular strip is pushed anteriorly to lie over the packing. One suture is placed subcutaneously postauricularly to stabilize the auricle. Transmeatally, the vascular strip is replaced in the ear canal in the exact position from which it came (Fig. 9-15). Gelfoam packing in the canal is completed, and a plug of cotton is placed in the outer meatus. The postauricular incision is closed with subcutaneous sutures, and a mastoid dressing is applied.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

The mastoid dressing is removed the day after surgery. The patient is given a postoperative instruction card (Appendix 2) just before entering the hospital. It is important to review some aspects of this information with the patient. The patient should be reminded not to blow the nose and not to get water in the ear. An antibiotic is prescribed and should be taken as directed on the prescription label. There will be discomfort for a few days, and the patient should take aspirin or acetaminophen four times a day regularly for the first few days to keep the pain under control. Nothing need be done with the cotton in the ear, but it may be changed if it becomes soiled.

PROS AND CONS OF OUTER SURFACE TECHNIQUE

One of the problems faced by a novice surgeon is that there are many techniques and prostheses recommended as “the best—always works well.” How well a technique or prosthesis works for the individual depends on the technical ability of that individual—his or her judgment and manual dexterity.11 The outer surface grafting technique has numerous advantages and disadvantages. The advantages are well known to all who have used the technique. First, the exposure is excellent—one can see everything necessary without moving the microscope. Second, one may remove as much remnant as necessary to eliminate the disease. There is no need to scrape in many different places. Third, the graft rate take is high. Fourth, it is one technique that can be used in all cases.

Healing Problems

One of the disadvantages of the outer surface grafting technique, as already noted, is that although there is a very high graft take rate regardless of how the operation is performed, there are healing problems. These healing problems may outweigh the advantages for some individuals.10 These healing problems became evident soon after the technique was started in the early 1960s: lateralization of the graft, blunting in the anterior sulcus, excessive membrane thickness, epithelial cysts between the remnant and the fascia, and epithelial pearls on the drum surface and ear canal. Most of these have ceased to be major problems, but they still occur in a small percentage of cases.

Lateralization of the Tympanic Membrane

The very first problem that was noticed with this technique was lateralization of the membrane (Fig. 9-16). This lateralization usually did not become apparent until 6 to 12 months after surgery, and resulted from the fascia not being placed under the malleus handle when the technique was first introduced (see Fig. 9-10). When lateralization has occurred, the patient’s hearing is reduced, but often not as much as anticipated. The appearance is of an eardrum smaller than normal-sized, mobile, and at a direct right angle to the line of vision. Treatment of this problem (if needed) requires reoperation and the placement of the new graft underneath the malleus handle.

Blunting in the Anterior Sulcus

Blunting in the anterior sulcus, particularly anterosuperiorly, occurs to a minor degree in most lateral surface cases, but is of no consequence and results from the formation of excess fibrous tissue. Blunting is probably the most common healing problem encountered by the novice surgeon. It can interfere greatly with the hearing result if it is great enough to involve the malleus handle when the ossicular chain is intact (Fig. 9-17).

Other Problems

An epithelial cyst may occur between the remnant and the fascia, and enlarge slowly over 1 to 2 years (Fig. 9-18). This is an uncommon problem that results from inadequate de-epithelialization of bone and the remnant adjacent to the bone. The only place where this is likely to occur is anteroinferiorly where the small vessel and nerve enter the ear canal 1 mm lateral to the drum. As opposed to blunting, in which there is a concave appearance, the appearance here is convex, and it occurs anteroinferiorly. When it is recognized, it can be corrected by incising the cyst and evacuating it.

1. Wullstein H. Theory and practice of tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 1956;66:1076-1093.

2. Zollner F. Principles of plastic surgery of the sound-conducting apparatus. J Laryngol Otol. 1955;69:637-652.

3. House W.F., Sheehy J.L. Myringoplasty: Use of ear canal skin compared with other techniques. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1961;73:407-415.

4. Plester D. skin and mucous membrane grafts in middle ear surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1960;72:718-721.

5. Storrs L.A. Myringoplasty with use of fascia graft. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1961;74:45-49.

6. Sheehy J.L. Tympanic membrane grafting: Early and long-term results. Laryngoscope. 1964;74:985-988.

7. Sheehy J.L., Glasscock M.E. Tympanic membrane grafting with temporalis fascia: A report of four years’ experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1967;86:391-402.

8. Sheehy J.L., Anderson R.G. Myringoplasty: A review of 472 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1980;89:331-334.

9. Sheehy J.L. Testing Eustachian tube function. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:562-564.

10. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E. Surgery of chronic otitis media. In: English G.M., editor. Otolaryngology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1994.

11. Sheehy J.L., Brackmann D.E.. Surgery of chronic ear disease: What we do and why we do it. Instructional Courses. Vol. 6, 1993. Mosby, St. Louis.

APPENDIX 1 RISKS AND COMPLICATIONS OF MYRINGOPLASTY, TYMPANOPLASTY, MASTOID SURGERY, AND OTHER OPERATIONS FOR CORRECTION OF CHRONIC EAR INFECTIONS

Tinnitus

Should the hearing be worse after surgery, tinnitus (head noises) likewise may be more pronounced.

APPENDIX 2 POSTOPERATIVE INSTRUCTION FOLDER: MYRINGOPLASTY, TYMPANOPLASTY, AND MASTOIDECTOMY

Precautions

Dizziness

Minor dizziness may be present on head motion and need not concern you unless it increases.