Tumour markers

The use of tumour markers

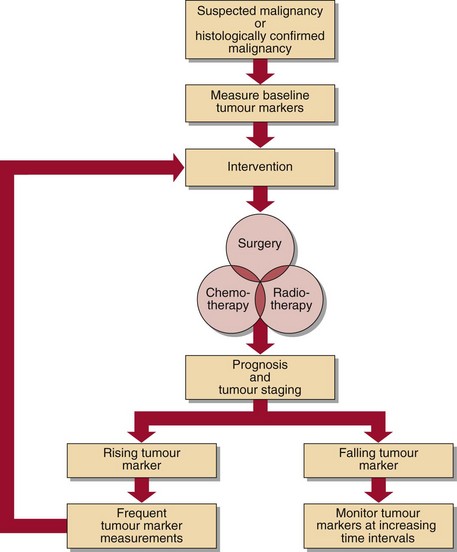

Tumour markers can be used in different ways. They are of most value in monitoring treatment and assessing follow-up (Fig 70.1), but are also used in diagnosis, prognosis and screening for the presence of disease.

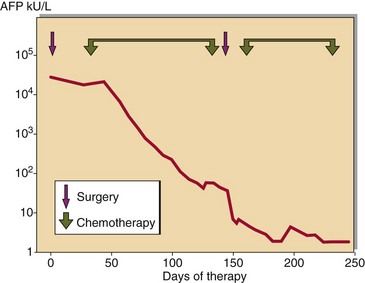

A practical application of tumour markers

Some of the uses of tumour markers discussed above can be illustrated with reference to Figure 70.2. This shows how the tumour marker AFP was helpful in the management of a young man with a malignant teratoma. The presence of AFP together with the hormone HCG confirmed the diagnosis. Between 75 and 95% of all patients presenting with testicular teratoma have abnormalities in one or both of these markers. The very high concentration of AFP (>10 000 kU/L) indicated that the prognosis was not good, and that it was likely there would be tumour recurrence after treatment. In fact, AFP concentrations fell in response to chemotherapy, and when the levels reached a plateau, surgery was carried out. Thereafter, chemotherapy was continued, and AFP fell to very low levels. Continued monitoring of AFP levels in such a patient would provide early warning of tumour recurrence.

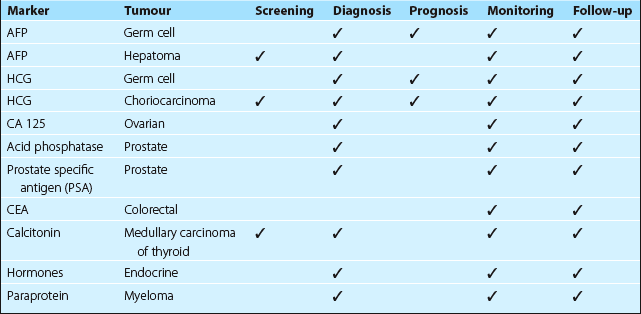

Tumour markers with established clinical value

Markers play a major role in the management of germ cell tumours and choriocarcinoma. Unfortunately, there are many cases in which markers are available but the tumours are resistant to chemotherapy, so their use is not mandatory. Table 70.1 shows which markers have gained an established place in the repertoire of tests commonly offered by the clinical biochemistry laboratory.