CHAPTER 9 Tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract

The esophagus

Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions

A diversity of benign tumors and related conditions occur in the esophagus. They are, however, mostly uncommon lesions and their main importance lies in distinction from malignant tumors (Crawford, 1999). Benign tumors are mostly mesenchymal in origin and lie within the esophageal wall. Clinically, they may be asymptomatic or produce dysphagia and sometimes bleeding (Choong and Meyers, 2003).

Leiomyomas

Leiomyomas are the most common benign non-epithelial tumors of the esophagus and are of smooth muscle origin (Postlethwait, 1983; Mutrie et al., 2005). Generally, they occur as a solitary 20–50 mm submucosal mass lesion at the lower one third of the esophagus, bulging into the lumen as a sessile intramural mass or as pedunculated polyps (Geboes, 2002). They may occur in up to 10% of adult esophagi but rarely attain a size to produce symptoms. If they are large they may ulcerate and produce pressure symptoms. Histologically, they are composed of interlacing smooth muscle fascicles with variable fibrosis and appear as a white whorled mass on gross examination (Mutrie et al., 2005).

Mesenchymal submucosal tumors

Other benign mesenchymal submucosal tumors include fibromas, lipomas, hemangiomas, neurofibromas and lymphangiomas; these, however, are very rare (Crawford, 1999).

Mucosal polyps

Mucosal polyps descriptively titled as fibrovascular polyps are composed of a combination of fibrous, vascular and adipose tissue covered by intact mucosa. They occur in the upper third of the esophagus and are often large and pedunculated (Ozcelik et al., 2004; Sultan, 2005).

Fibrous polyps

Fibrous polyps are also known as inflammatory pseudotumors and are considered to be reactive non-neoplastic lesions. They are located in the upper or mid esophagus as sessile or pedunculated lesions and may attain a large size. On microscopic examination, these lesions comprise myomatous fibrous tissue with thin walled blood vessels. Mucosal ulceration is present and hence mimics a malignant lesion. Biopsy is essential to distinguish between the two (Santos et al., 2004; Ozolek et al., 2004).

Inflammatory reflux polyps

Inflammatory reflux polyps are a special variant and are made up mostly of granulation tissue situated in the lower esophagus. They are thought to be related to reflux disease and hence the term reflux or gastro-esophageal polyp-fold complex. They are not pre-malignant (Geboes, 2002).

Squamous papillomas

Squamous papillomas are smooth, round, pink, sharply demonstrated, sessile lesions. They are usually single but occasionally multiple lesions with a central fibrovascular connective tissue core covered by bland hyperplastic papilliform squamous mucosa. The age range for presentation is between 17 and 78 years. These rare lesions are typically found in the lower esophagus and range over a few millimeters to 200 mm in diameter (Mosca et al., 2001; Geboes, 2002). In some cases, human papilloma virus (HPV) antigen has been identified (Woo and Yoon, 1996). The distinction between squamous papilloma and viral wart is unclear and, indeed, they may be related. There is no association with malignancy but they may recur after resection.

Malignant lesions

Most esophageal cancers are either squamous cell carcinomas or adenocarcinomas. Rare, uncommon and aggressive lesions include small cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, melanoma and carcinoma with a spindle cell component. Metastatic tumors can involve the esophagus by direct spread from the stomach and upper and lower respiratory tract. Rare blood-borne metastasis may occur from distant sites (Crawford, 1999).

Squamous cell carcinoma

Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for most esophageal cancers. It occurs in adults over the age of 50 with a male predominance; the male:female ratio is 4:1. There are wide geographical variations in its incidence. Areas of high rate of incidence include Puerto Rico, South Africa, Central Asia, Northern China and Eastern Europe. Low risk areas include most of Western Europe and North America (Crawford, 1999). The major risk factors are alcohol and tobacco (Bahmanyar and Ye, 2006; Hashibe et al., 2007). Human papilloma virus (HPV) has also been implicated as a probable etiological factor in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (Woo and Yoon 1996; Matsha et al., 2007). Dietary and environmental factors have been proposed to increase the risk and nutritional deficiencies act as promoters and potentiators of the tumorigenic effects of environmental carcinogens (Bahmanyar and Ye, 2006). Broad spectrum p53 gene point mutations present in these tumors are related to the effects of methylating nitroso compounds in the diet and in tobacco smoke (Meltzer, 1996; Mandard et al., 1997). Mutations in p16 gene and allelic loss involving other chromosomes are prevalent in these cancers as well, in keeping with the step-wise acquisition and accumulation of genetic alterations which ultimately give rise to cancer (Meltzer, 1996; Fujiki et al., 2002).

Clinically, it has an insidious onset and produces dysphagia and obstruction gradually. Weight loss and debilitation result from impaired nutrition and the effects of the tumor itself. Hemorrhage and sepsis occur with tumor ulceration (Crawford, 1999). Complications include aspiration of food through a cancerous tracheo-esophageal fistula and extension into adjacent mediastinal structures (Anderson and Lad, 1982).

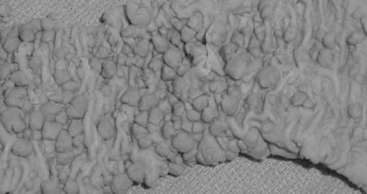

Most frequently, it occurs in the lower two thirds of the esophagus. Morphologically, early lesions appear as small gray-white plaque-like thickening or mucosal elevations (Sugimachi et al., 1989). Late lesions are tumor masses which may eventually encircle the lumen and present as polypoid fungating exophytic masses (Figure 9.1), flat diffuse infiltrative forms or deeply irregular excavated ulcers with nodular margins (Mandard et al., 1984).

The microscopic appearances are similar as in squamous cell carcinoma anywhere else. The degree of differentiation may vary and variation within a tumor is common. The histological criteria are keratinization and intercellular bridges, which are prominent in well-differentiated carcinoma, sparse and focal in poorly differentiated tumors (Fletcher et al., 2000). Dysplastic squamous epithelium frequently borders invasive squamous cell carcinoma and represents the histological precursor (Sugimachi et al., 1989). This epithelium is characterized by varying degrees of altered maturation and cytoplasmic differentiation with nuclear pleomorphism, hyperchromasia, irregular chromatin and abnormal mitoses (Kuwano et al., 1987).

Five-year survival with superficial carcinoma is 75% compared with less than 25% in patients with advanced disease (Fletcher et al., 2000). Local and distant recurrence after surgery is common. The important prognostic features in a resection specimen are tumor size, depth of invasion, presence of lymph node metastasis and status of resection margins (Edwards et al., 1989; Lam et al., 1996).

Adenocarcinoma

The vast majority of primary esophageal adenocarcinomas arise in the lower esophagus in a background of columnar metaplasia, also known as Barrett’s esophagus, and hence are associated with chronic gastro-esophageal reflux (Haggitt, 1994; Williams et al., 2006; Sayana et al., 2007; De Jonge et al., 2007). Rare adenocarcinomas arising from ectopic gastric mucosa are distinguished by their location in the upper esophagus (Christensen and Sternberg, 1987). Adenocarcinoma arising in the setting of Barrett’s esophagus occurs in patients over 40 years with a median age in their 50s with an increasing incidence in the Western population (Williams et al., 2006; Sayana et al., 2007). Although the exact pathogenesis is unclear, genetic alterations in this disease are well documented.

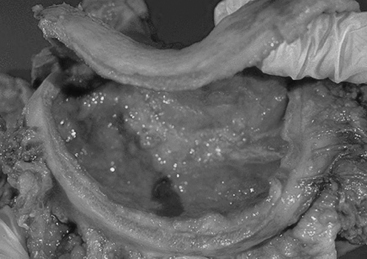

Barrett’s esophagus is a condition in which the normal stratified squamous epithelium is replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium that predisposes to the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma (Figures 9.2, 9.3, see color insert) and Figure 9.4 (Haggitt, 1994). Neoplastic progression in Barrett’s esophagus occurs by a multistep process associated with genomic instability and the development of aneuploid cell populations (Ramel et al., 1992). Molecular and immunohistochemical studies have suggested that mutations of the p53 gene accompanied by chromosome 17p allelic loss play an important role in the pathogenesis of the tumor (Fitzgerald, 2005; Sayana et al., 2007). p53 protein over-expression and allelic deletions on chromosome 17p have been shown to be present in some Barrett’s adenocarcinomas (Ramel et al., 1992).

Endoscopically, early cancers appear as flat lesions, while advanced cancers present as large ulcerating, fungating, polypoid or diffusely infiltrating masses (Geboes, 2002). Microscopically, these are mucin-producing glandular tumors with a tubular or papillary appearance exhibiting irregular invasive intestinal type glands lined by cytologically malignant cells (Fletcher et al., 2000). Since most cases arise in a background of Barrett’s esophagus, high grade dysplasia in a background of Barrett’s type metaplastic glandular epithelium is common in the adjacent mucosa (Williams et al., 2006; Sayana et al., 2007).

As with other forms of esophageal carcinoma, most patients present at an advanced stage with dysphagia, progressive weight loss, bleeding and chest pain (Crawford, 1999). The prognosis is poor; the mortality from esophageal adenocarcinoma exceeds 80% at 5 years (Fitzgerald, 2005). Resection of early cancers, limited to the mucosa and submucosa, improves the survival rate by 80% (Fletcher et al., 2000).

The stomach

Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions

Gastric polyps are clinically important lesions that are frequently encountered in routine pathology (2–3% of all gastroscopies). They may occur sporadically or in polyposis syndromes, such as familial adenomatous polyposis coli (FAP), Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, juvenile polyposis, Cowden’s disease and Cronkhite-Canada syndrome. Sporadic polyps are classified as fundic gland polyps and hamartomatous and heterotopic tissue polyps; reactive polypoid lesions which include regenerative/hyperplastic polyps and inflammatory fibroid polyps (Oberhuber and Stolte, 2000; Borch et al., 2003).

Regenerative/hyperplasic polyps

Regenerative/hyperplasic polyps are one of the commonest types of gastric polyps. They are thought to arise from excessive regeneration following mucosal damage. Coexistent gastric abnormalities include chronic gastritis, partial gastrectomies, Helicobacter pylori and intestinal metaplasia (Gencosmanoglu et al., 2003). They are sessile or pedunculated with a smooth or lobulated surface (Figure 9.5). They are usually multiple and vary from few millimeters to 40 mm (Gencosmanoglu et al., 2003; Santos et al., 2004). Microscopically, there is hyperplasia of gastric foveolae leading to elongated and tortuous glands with cystic change and irregular branching. The stroma is edematous with infiltrated chronic inflammatory cells and contains smooth muscle fibers from the muscularis mucosa (Figure 9.6, see color insert) (Haboubi, 2002a). They are mostly benign and occasionally are complicated by carcinoma (Geboes, 2002). The incidence of synchronous or metachronous cancer elsewhere in the stomach is up to 3% of cases (Geboes, 2002). In cases of multiple hyperplastic polyps, however, there is a greater incidence of carcinoma associated with the polyps and synchronous cancers are significantly more commonly seen. Treatment for solitary polyps is polypectomy. Where multiple polyps exist, close follow up is required. They may recur after polypectomy.

Inflammatory fibroid polyps

Inflammatory fibroid polyps are tumor-like lesions. These are rare lesions and can occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract, but most commonly occur in the stomach (see esophagus) (Haboubi, 2002a). These are bulky growths involving mucosa and submucosa, composed of vascularized and inflamed fibromuscular tissue with a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate and covered by a thin mucosa (Harned et al., 1992; Santos et al., 2004). They are solitary lesions most commonly located in the antrum. They protrude into the lumen and may occlude the pyloric channel abruptly and present as gastric outlet obstruction (Mutrie et al., 2005). They are benign and not known to be associated with cancer. Treatment is polypectomy.

Adenomas

Adenomatous polyps are true neoplasms and contain proliferative dysplastic epithelium and thereby have malignant potential. They may be sessile without a stalk or pedunculated (stalked). The most common location is the antrum. The lesions are usually single and may grow up to 3–4 cm (Gencosmanoglu et al., 2003). Malignant transformation is related to size and is rare if the polyp is under 2 cm. Over 2 cm, malignancy is seen in 40–50% of adenomas. Polypectomy is the treatment of choice.

Malignant lesions

Gastric adenocarcinoma is the commonest malignant lesion of the stomach. Less common gastric tumours include gastric lymphomas, neuroendocrine tumors and mesenchymal tumors (Crawford, 1999).

Adenocarcinoma

Adenocarcinoma accounts for most gastric cancers. Males are affected more commonly with a male:female ratio of 2:1. High incidence areas include Japan, Central and South America and some parts of northern and eastern Europe (Crawford, 1999). From the epidemiological point of view, environmental factors implicated in gastric cancer include low socioeconomic status, smoking, alcohol consumption and diet, particularly high intake of salt, dried and pickled food (Lynch et al., 2005). Precancerous conditions include chronic gastritis associated with long-standing H. pylori infection, atrophy and intestinal metaplasia, Menitriers disease and possibly long-standing peptic ulcer (Crawford, 1999). E-cadherin germ line mutations are seen in familial gastric cancers (Guilford et al., 1998; Lynch et al., 2005).

Early gastric cancer, also termed surface or superficial carcinoma, is confined to the mucosa and submucosa and is a potentially curable stage even if there is lymph node metastasis. Macroscopically, this may appear as an uneven mucosal surface or as a nodular, polypoid or villous form (Haboubi, 2002a).

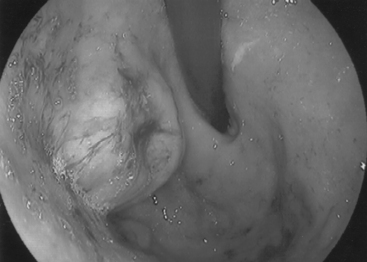

Advanced gastric cancers may take the form of a polypoid, fungating, ulcerated or diffusely infiltrating form also known as the linitis plastica type (Figure 9.7) or may show a combination of these (Crawford, 1999). The diffusely infiltrating form occurs as an ill-defined, superficially ulcerating plaque accompanied by conspicuous thickening of the underlying gastric wall, or as diffuse thickening of the entire stomach (known as the leather bottle stomach). Hence the production of excess extracellular mucin gives the tumor a gelatinous appearance (Lynch et al., 2005).

Microscopically, the Lauren classification system classifies gastric carcinoma under two major histopathological variants, an intestinal type and a diffuse type. The intestinal type exhibits components of glandular, solid or intestinal architecture, as well as tubular structures. The diffuse type (linitis plastica) pathology is characterized by poorly cohesive clusters of signet ring cells infiltrating the gastric wall, leading to its widespread thickening and rigidity (Figure 9.8, see color insert) (Lauren, 1965). The outcome of advanced gastric cancer is usually poor and depends on accurate staging, i.e. extent and local infiltration, lymph node and extranodal metastasis.

Neuroendocrine tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors, also known as carcinoids, originate from the enterochromaffin cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa (Norton et al., 2004; Borch et al., 2005, Robertson et al., 2006). These lesions comprise less than 1% of gastric tumors (Haboubi, 2002a). In view of the distinct pathological behavior of gastric carcinoids, it has been proposed (Modlin et al., 1995) that they are divided into three types:

Both types 1 and 2 represent syndromes with multiple small polyps, associated with hypergastrinemia and having low invasive or metastasizing potential. Sporadic lesions are almost always solitary; they evolve in a background of normal gastric mucosa and display a moderately aggressive behavior with the ability to metastasize (Haboubi, 2002a). Rarely, they present with clinical effects related to the hypersecretion of the peptide hormone, serotin, as carcinoid syndrome (Borch et al., 2005; Robertson et al., 2006).

Macroscopically, they appear as small, smooth, well-circumscribed polypoid elevations with a yellow-gray cut surface involving mucosa and submucosa. Larger tumors involve full thickness of the wall and may show central ulceration (Soga, 2005; Borch et al., 2005). Microscopically, gastric carcinoids are composed of small uniform polygonal to cuboidal cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm dispersed in the form of nests, trabeculae or cords involving mucosa and submucosa (Yu et al., 1998; Haboubi, 2002a). Malignant tumors are characterized by a more infiltrative pattern of growth, areas of necrosis, cytological atypia and mitoses (Yu et al., 1998).

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)

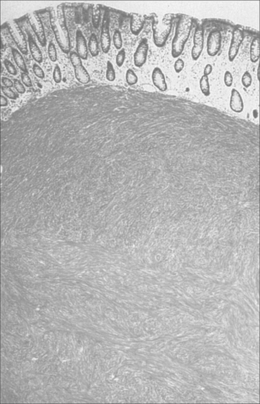

A wide variety of mesenchymal neoplasms may occur broadly classified under the term gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs). They occur most commonly in the stomach (Artigau et al., 2006). These tumors are thought to originate from mesenchymal stem cells that differentiate toward the interstitial cells of Cajal (ICCs). They express the tyrosine kinase c-kit (CD117) activity receptor. Mutations in this receptor cause neoplastic development (Artigau et al., 2006; Miettinen and Lasota, 2006a). These tumors occur in adults over 30 years of age, with males and females equally affected (Miettinen and Lasota, 2006b). Macroscopically, they may be single or multiple and vary in size from a few millimeters to 100 mm, presenting as small intramural lesions to bulky tumor masses which can occur in any part of the stomach (Geboes, 2002). Most tumors are well-circumscribed unencapsulated lesions that project into the gastric lumen as exophytic polypoid submucosal growths and are prone to surface ulceration (Figure 9.9) (Haboubi, 2002a; Alvarado-Cabrero et al., 2007). Microscopically, they are composed of interlacing bundles or whorls of uniform spindle cells or epithelioid cells (Alvarado-Cabrero et al., 2007) (Figure 9.10). Tumors over 50 mm are considered malignant. Other useful features suggestive of malignancy are increased mitoses, hypercellularity, nuclear pleomorphism and necrosis (Miettinen and Lasota, 2006a). Surgery still remains the main stay therapy but other treatment modalities are being successfully introduced.

Lymphomas

Gastric lymphomas represent 5% of all gastric malignancies. They may be primary or secondary to systemic lymphoma (Crawford, 1999). The great majority of primary gastric lymphomas are of B cell origin arising from mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) (Bacon et al., 2007). Virtually all tumors arise in a background of helicobacter-associated gastritis (Moss and Malfertheiner, 2007). Macroscopically, they appear as polypoid, fungating or ulcerating tumors, most commonly located at the antrum. Microscopy shows a heavy population of polymorphous B lymphocytes infiltrating diffusely into the mucosa and invading gastric glands to form lymphoepithelial lesions with florid destruction of gastric glands (Figure 9.11, see color insert) (Bacon et al., 2007).

Outcome relates to the type of lymphoma; small cell type has a better prognosis than large cell type. Treatment modality includes eradication of H. pylori in the early stages of tumor development. In advanced disease, surgery is recommended.

The duodenum

Benign tumors and tumor-like lesions

Peutz-Jeghers polyps

Peutz-Jeghers polyps are hamartomatous lesions associated with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and characterized by gastrointestinal polyposis, oral pigmentation and an autosomal mode of inheritance (Giardiello and Trimbath 2006; Zbuk and Eng, 2007). They are composed of coarse bands of extensively branching smooth muscle with an arborizing pattern covered by normal appearing glandular epithelium (Zbuk and Eng, 2007). Displacement of epithelium may occur within the submucosa and muscular coat (Jass, 2000).

Brunner’s gland hamartoma

Other hamartomatous lesions include Brunner’s gland hamartoma. This consists of a sessile mass composed of proliferated but otherwise normal appearing Brunner’s glands with associated ducts and stroma (Bal et al., 2007).

Hyperplastic lesions

Hyperplastic lesions include lymphoid hyperplasia and Brunner’s gland hyperplasia (Haboubi, 2002b).

Duodenal heterotropia

Duodenal heterotropia is comprised of heterotropic gastric mucosa which most often occurs in the first part of the duodenum as single or multiple nodules less than 10 mm, located in the submucosa or intramurally. Heterotropic gastric mucosa comprises an orderly collection of gastric glands, ducts and lamina propria (Spiller et al., 1982).

Adenomas

Adenomatous polyps

Duodenal adenomatous polyps are rare. The commonest site is the periampullary region suggesting there is a role for bile secretion in the genesis of the adenomas. They are usually single. They vary in size from microscopic lesions to large sessile or pedunculated lesions (Haboubi, 2002b). Multiple duodenal adenomas may occur in the setting of familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) (Spigelman et al., 1994). Some may remain small, others progress to frank malignancy (Haboubi, 2002b).

The microscopic appearances are similar to their colonic counterparts with a tubular, villous or tubulovillous morphology displaying varying degrees of dysplasia, although absorptive type columnar cells are more prominent (Jass, 2000; Heidecke et al., 2002). However, unlike the colon, the presence of neoplastic epithelium in the lamina propria is a strong indicator of malignancy (Haboubi, 2002b). In patients with FAP, there is strong evidence to support the adenoma–carcinoma sequence (Spigelman et al., 1994).

Malignant lesions

Duodenal adenocarcinoma

Duodenal adenocarcinoma is an uncommon tumor and comprises 0.3% of all gastrointestinal tumors (Haboubi, 2002b). Carcinoma may develop in a background of familial adenomatous polyposis, celiac disease or Crohn’s disease (Jass, 2000). Most cases occur in the periampullary region and present as obstructive jaundice. Macroscopically, these tumors grow in an annular ring encircling pattern or as polypoid or fungating masses (Hung et al., 2007). Microscopically, the appearances are similar to carcinoma elsewhere in the GI tract with varying degrees of differentiation. The cell population may include absorptive secretory and, to a lesser extent, Paneth and endocrine cells (Haboubi, 2002b). It is common to see an associated adenomatous component emphasizing the adenoma–carcinoma sequence (Perzin and Bridge, 1981). At the time of diagnosis, most tumors have already penetrated the bowel wall, invaded the mesentery or other segments of the gut (Hung et al., 2007).

Neuroendocrine tumors

Duodenal carcinoids are rare lesions and account for 1–2% of all gastro-intestinal carcinoids (Modlin et al., 2003). They may be single or multiple and vary in size from 2 to 50 mm and occur in the first and second parts of the duodenum (Haboubi, 2002b). Macroscopically, they appear as small polypoid masses with a characteristic solid yellow tan appearance (Jass, 2000). Microscopically, they are composed of small monotonous cells dispersed in an organoid pattern with granular cytoplasm and speckled nuclear chromatin (Figure 9.12, see color insert) (Bal et al., 2007). Carcinoid tumors produce a variety of polypeptide hormones. Some carcinoids are associated with other conditions including Zollinger Ellison syndrome, Von Recklinghausen disease, gastrinoma, pheochromocytoma and multiple endocrine neoplasia (Jass, 2000). Malignancy in carcinoids is related to a size more than 20 mm, mitoses and invasion of the muscularis propria (Haboubi, 2002b).

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs)

Only 3–5% of GISTs occur in the duodenum and more commonly occur in the first part of the duodenum (Kwon et al., 2007). The appearances are similar to those occurring elsewhere is the gastrointestinal tract.

Lymphomas

Long-standing celiac disease is a predisposing factor for the development of lymphoma. These lymphomas are of T cell origin (Farrell and Kelly, 2001; Silano et al., 2007). They appear as multifocal ulcerating plaques with expansions of the mucosa and submucosa. The diffusely infiltrating lesions produce full thickness mural thickening with loss of mucosal folds and focal ulcerations. Others may be polypoid or fungating ulcerated masses (Jass, 2000; Haboubi, 2002b). Microscopically, these lesions are composed of a pleomorphic population of T lymphocytes (Isaacson, 2005). The adjacent mucosa shows villous atrophy with crypt hyperplasia and infiltration of the crypt epithelium with T lymphocytes (Yasuoka et al., 2007).

Alvarado-Cabrero I., Vázquez G., Sierra Santiesteban F.I., et al. Clinicopathologic study of 275 cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: the experience at 3 large medical centers in Mexico. Ann. Diagn. Pathol.. 2007;11(1):39-45.

Anderson L.L., Lad T.E. Autopsy findings in squamous-cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Cancer. 1982;50(8):1587-1590.

Artigau A., Luna A., Dalmau P., et al. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: experience in 49 patients. Clin. Transl. Oncol.. 2006;8(8):594-598.

Bacon C.M., Du M.Q., Dogan A. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for pathologists. J. Clin. Pathol.. 2007;60(4):361-372. Epub 2006 Sep 1

Bahmanyar S., Ye W. Dietary patterns and risk of squamous-cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and adenocarcinoma of the gastric cardia: a population-based case-control study in Sweden. Nutr. Cancer. 2006;54(2):171-178.

Bal A., Joshi K., Vaiphei K., Wig J.D. Primary duodenal neoplasms: a retrospective clinico-pathological analysis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13(7):1108-1111.

Borch K., Ahrén B., Ahlman H., et al. Gastric carcinoids: biologic behavior and prognosis after differentiated treatment in relation to type. Ann. Surg.. 2005;242(1):64-73.

Borch K., Skarsgård J., Franzén L., et al. Benign gastric polyps: morphological and functional origin. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 2003;48(7):1292-1297.

Choong C.K., Meyers B.F. Benign esophageal tumors: introduction, incidence, classification, and clinical features. Seminars in Thoracic Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;15(1):3-8.

Christensen W.N., Sternberg S.S. Adenocarcinoma of the upper esophagus arising in ectopic gastric mucosa. Two case reports and review of the literature. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.. 1987;11(5):397-402.

Contini S., Zinicola R., Bonati L., et al. Heterotopic pancreas in the ampulla of Vater. Minerva Chirurgie. 2003;58(3):405-408.

Crawford J.M. The gastrointestinal tract. In Kotran R.S., Kumar V., Collins T., editors: Robbins pathologic basis of disease, sixth ed., WB Saunders Company, 1999.

De Jonge P.J., Wolters L.M., Steyerbery E.W., et al. Environmental risk factors in the development of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus or gastric cardia: a cross-sectional study in a Dutch cohort. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther.. 2007;26(1):31-39.

Edwards J.M., Hillier V.F., Lawson R.A., et al. Squamous carcinoma of the oesophagus: histological criteria and their prognostic significance. Br. J. Cancer. 1989;59(3):429-433.

Farrell R.J., Kelly C.P. Diagnosis of celiac sprue. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3237-3246.

Fitzgerald R.C. Genetics and prevention of oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Research. 2005;166:35-46.

Fletcher C.F., Bogomoletz V., Williams G.T. Tumours of the oesophagus and stomach. In Fletcher C.D.M., editor: Diagnostic histopathology of tumours, second ed., Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Fujiki T., Haraoka S., Yoshioka S., et al. p53 gene mutation and genetic instability in superficial multifocal esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol.. 2002;20(4):669-679.

Geboes K. Polyps of the oesophagus. In: Haboubi N., Geboes K., Shepard N., Talbot I., editors. Gastrointestinal polyps. London, San Francisco: Greenwich Medical Media; 2002:1-21.

Gencosmanoglu R., Sen-Oran E., Kurtkaya-Yapicier O., et al. Gastric polypoid lesions: analysis of 150 endoscopic polypectomy specimens from 91 patients. World J. Gastroenterol. 2003;9(10):2236-2239.

Giardiello F.M., Trimbath J.D. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and management recommendations. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2006;4(4):408-415.

Guilford P., Hopkins J., Harroway J., et al. E-cadherin germline mutations in familial gastric cancer. Nature. 1998;392(6674):402-405.

Haboubi N.Y. Polyps of the stomach. In: Haboubi N., Geboes K., Shepard N., Talbot I., editors. Gastrointestinal polyps. London, San Francisco: Greenwich Medical Media; 2002:23-48.

Haboubi N.Y. Polyps of the duodenum. In: Haboubi N., Geboes K., Shepard N., Talbot I., editors. Gastrointestinal polyps. London, San Francisco: Greenwich Medical Media; 2002:53-67.

Haggitt R.C. Barrett’s esophagus, dysplasia, and adenocarcinoma. Hum. Pathol.. 1994;25(10):982-993.

Harned R.K., Buck J.L., Shekitka K.M. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: radiologic evaluation. Radiology. 1992;182(3):863-1836.

Hashibe M., Boffetta P., Zaridze D., et al. Esophageal cancer in Central and Eastern Europe: tobacco and alcohol. Int. J. Cancer. 2007;120(7):1518-1522.

Heidecke C.D., Rosenberg R., Bauer M., et al. Impact of grade of dysplasia in villous adenomas of Vater’s papilla. World J. Surg.. 2002;26(6):709-714.

Hung F.C., Kuo C.M., Chuah S.K., et al. Clinical analysis of primary duodenal adenocarcinoma: an 11-year experience. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2007;22(5):724-728.

Isaacson P.G. Gastrointestinal lymphoma: where morphology meets molecular biology. J. Pathol.. 2005;205(2):255-274.

Jass J.R. Tumours of the small and large intestine. In Fletcher C.D.M., editor: Diagnostic histopathology of tumours, second ed., Churchill Livingstone, 2000.

Kuwano H., Matsuda H., Matsuoka H., et al. Intra-epithelial carcinoma concomitant with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1987;59(4):783-787.

Kwon S.H., Cha H.J., Jung S.W., et al. A gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the duodenum masquerading as a pancreatic head tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007;13(24):3396-13369.

Lam K.Y., Ma L.T., Wong J. Measurement of extent of spread of oesophageal squamous carcinoma by serial sectioning. J. Clin. Pathol.. 1996;49(2):124-129.

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma; diffuse and so called intestinal type carcinoma. An attempt at a histoclinical classification. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand.. 1965;64:31-49.

Lynch H.T., Grady W., Suriano G., et al. Gastric cancer: new genetic developments. J. Surg. Oncol.. 2005;90(3):114-133. discussion 133

Mandard A.M., Marnay J., Gignoux M., et al. Cancer of the esophagus and associated lesions: detailed pathologic study of 100 esophagectomy specimens. Hum. Pathol.. 1984;15(7):660-669.

Mandard A.M., Marnay J., Lebeau C., et al. Expression of p53 in oesophageal squamous epithelium from surgical specimens resected for squamous cell carcinoma of the oesophagus, with special reference to uninvolved mucosa. J. Pathol.. 1997;185(3):334-335.

Matsha T., Donninger H., Erasmus R.T., et al. Expression of p53 and its homolog, p73, in HPV DNA positive oesophageal squamous cell carcinomas. Virology. 2007;369(1):182-190. Epub 2007 Aug 29

Meltzer S.J. The molecular biology of esophageal carcinoma. Recent Results Cancer Research. 1996;142:1-8.

Miettinen M., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: review on morphology, molecular pathology, prognosis, and differential diagnosis. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med.. 2006;130(10):1466-1478.

Miettinen M., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors: pathology and prognosis at different sites. Semin. Diagn. Pathol.. 2006;23(2):70-83.

Modlin I.M., Gillian C.J., Lawton G.P., et al. Gastric carcinoids. The Yale experience. Arch. Surg.. 1995;130:250-255.

Modlin I.M., Lye K.D., Kidd M.A. 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97(4):934-959.

Morandi E., Pisoni L., Castoldi M., et al. Gastric outlet obstruction due to inflammatory fibroid polyp. Ann. Ital. Chir.. 2006;77(1):59-61.

Mosca S., Manes G., Monaco R., et al. Squamous papilloma of the esophagus: long-term follow up. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2001;16(8):857-861.

Moss S.F., Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter and gastric malignancies. Helicobacter. 2007;12(Suppl. 1):23-30.

Mutrie C.J., Donahue D.M., Wain J.C., et al. Esophageal leiomyoma: a 40-year experience. Ann. Thorac. Surg.. 2005;79(4):1122-1125.

Norton J.A., Melcher M.L., Gibril F., et al. Gastric carcinoid tumors in multiple endocrine neoplasia-1 patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome can be symptomatic, demonstrate aggressive growth, and require surgical treatment. Surgery. 2004;136(6):1267-1274.

Oberhuber G., Stolte M. Gastric polyps: an update of their pathology and biological significance. Virchows Arch.. 2000;437(6):581-590.

Ozcelik C., Onat S., Dursun M., et al. Fibrovascular polyp of the esophagus: diagnostic dilemma. Interac. Cardiovasc. Thorac. Surg.. 2004;3(2):260-262.

Ozolek J.A., Sasatomi E., Swalsky P.A., et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyps of the gastrointestinal tract: clinical, pathologic, and molecular characteristics. Appl. Immunohistochem. Mol. Morphol.. 2004;12(1):59-66.

Perzin K.H., Bridge M.F. Adenomas of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases and a study of their relationship to carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48(3):799-819.

Postlethwait R.W. Benign tumors and cysts of the esophagus. Surg. Clin. N. Am.. 1983;63(4):925-931.

Ramel S., Reid B.J., Sanchez C.A. Evaluation of p53 protein expression in Barrett’s esophagus by two-parameter flow cytometry. Gastroenterology. 1992;102(4 Pt 1):1220-1228.

Robertson R.G., Geiger W.J., Davis N.B. Carcinoid tumors. Am. Fam. Physician. 2006;74(3):429-434.

Santos G.C., Alves V.A., Wakamatsu A., et al. Inflammatory fibroid polyp: an immunohistochemical study. Arq. Gastroenterol. 2004;41(2):104-107. Epub 2004 Oct 27.

Sayana H., Wani S., Sharma P. Esophageal adenocarcinoma and Barrett’s esophagus. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol.. 2007;53(2):157-169.

Silano M., Volta U., Vincenzi A.D., et al. Effect of a gluten-free diet on the risk of enteropathy-associated T-cell lymphoma in celiac disease. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 2007. Oct 13 [Epub ahead of print]

Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103(8):1587-1595.

Spigelman A.D., Talbot I.C., Penna C.. Evidence for adenoma-carcinoma sequence in the duodenum of patients with familial adenomatous polyposis [The Leeds Castle Polyposis Group (Upper Gastrointestinal Committee). J. Clin. Pathol., 1994;47(8):709-710..

Spiller R.C., Shousha S., Barrison I.G. Heterotopic gastric tissue in the duodenum: a report of eight cases. Dig. Dis. Sci.. 1982;27(10):880-883.

Sugimachi K., Ohno S., Matsuda H., et al. Clinicopathologic study of early stage esophageal carcinoma. Br. J. Surg.. 1989;76(7):759-763.

Sultan P.K. Fibrovascular polyps of the esophagus. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg.. 2005;130(6):1709-1710.

Williams L.J., Guernsey D.L., Casson A.G. Biomarkers in the molecular pathogenesis of esophageal (Barrett) adenocarcinoma. Curr. Oncol.. 2006;13(1):33-43.

Woo Y.J., Yoon H.K. In situ hybridization study on human papillomavirus DNA expression in benign and malignant squamous lesions of the esophagus. J. Korean Med. Sci.. 1996;11(6):467-473.

Yasuoka H., Masuo T., Hashimoto K., et al. Enteropathy-type T-cell lymphoma that was pathologically diagnosed as celiac disease. International Medicine. 2007;46(15):1219-1224. Epub 2007 Aug 2

Yu J.Y., Wang L.P., Meng Y.H., et al. Classification of gastric neuroendocrine tumors and its clinicopathologic significance. World J. Gastroenterol. 1998;4(2):158-161.

Zbuk K.M., Eng C. Hamartomatous polyposis syndromes. Nat. Clin. Pract. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.. 2007;4(9):492-502.