CHAPTER 14 Tumors of the small and large intestine

Introduction

Small and large intestinal tumors are broadly classified into non-neoplastic (or tumor-like lesions) and neoplastic tumors (Table 14.1) most of which are epithelial (arise from the surface epithelium) and the minority are non-epithelial tumors (stromal). Non-neoplastic lesions are those which follow a benign course and do not have a tendency for malignant transformation as opposed to neoplastic tumors, which are pre-malignant from which carcinoma arises (Kumar et al., 2004; Robertson and Levison, 2006).

Table 14.1 Classification of tumors of small and large intestines

Colorectal cancer is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide (Geboes et al., 2005). Around 100 new cases of colorectal cancer are diagnosed each day in the UK and it is the third most common cancer after breast and lung (Cancer Research UK, 2007). Epithelial tumors of the small intestine are rare compared to the large intestine.

Both neoplastic and non-neoplastic lesions of the small and large intestines commonly present in the form of a polyp, which is defined as a raised lesion above the mucosa that protrudes into the lumen of the digestive tract (Geboes et al., 2005).

Non-neoplastic/tumor-like lesions

Hyperplastic/metaplastic polyps and serrated adenomas

Hyperplastic polyps are benign epithelial lesions that are usually small and less than 5 mm in maximum diameter. By definition, they do not display dysplasia (see glossary for definition) and, in most instances, they are not pre-neoplastic in nature. They are usually asymptomatic and can be multiple and they mainly involve the large intestine rather than the small intestine (Robertson and Levison, 2006). Histologically, they are composed of well-formed glands lined by non-neoplastic epithelial cells, most of which show maturation with small, regular nuclei located in the base of the cells (Geboes et al., 2005). They are found in approximately 40% of rectal specimens in people younger than 40 years and in 75% of older persons (Rubin and Strayer, 2007). They are usually limited to the large bowel and are believed to arise due to a defect in proliferation and maturation of normal mucosal epithelium (Geboes et al., 2005). Typically, the luminal epithelium shows hyperplastic change with the typical intraluminal infoldings resulting in a saw-toothed appearance (Rosai, 2004; Geboes et al., 2005). By definition, hyperplastic polyps have no malignant potential; however, this stance has recently been challenged and, in some cases, adenocarcinomas of the colon have been found to contain residual adenomatous and hyperplastic epithelium (Robertson and Levison, 2006). In patients with hyperplastic polyposis syndrome, the polyps tend to be large and sometimes associated with adenocarcinoma (Leggett et al., 2001). Recently, on the genetic level, these polyps are shown to contain K-ras mutation which is a mutation commonly associated with colorectal cancer (CRC) (Day et al., 2003).

In recent years, there has been growing evidence that there is a subgroup of hyperplastic polyps that are not homogeneous and are termed serrated adenomas. They are polyps showing both hyperplastic and adenomatous change (Longacre and Fenoglio-Preiser, 1990) and have a higher incidence of microsatellite instability (see glossary for definition) and increased risk of development of carcinoma (Day et al., 2003).

Hyperplastic polyposis encompasses a large number of hyperplastic polyps, which are distributed throughout the large bowel and are usually more than 1 cm in size (Williams et al., 1980). This disease is associated with increased risk of malignancy and usually associated with adenomatous polyps.

Juvenile polyps

These represent focal hamartomatous non-neoplastic malformations of the mucosal epithelium and the vast majority occur in children less than 5 years of age (Robertson and Levison, 2006). Most involve the rectum with an equal male and female distribution and gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common presentation (Day et al., 2003).

Histologically, the lamina propria is usually abundant and encloses cystically dilated glands together with abundant inflammation and frequent ulceration. They have no malignant potential (Nugent et al., 1993). However, when they occur in the setting of juvenile polyposis syndrome (a rare autosomal dominant disease), they do carry a higher risk of malignancy and, in this setting, most cancers occur between the age of 20 and 40 years (Robertson and Levison, 2006).

Peutz-Jeghers (PJ) polyps

These are also a hamartomatous type of lesion that involve the upper and lower gastrointestinal tract and are more frequently found in the small bowel rather than the large bowel. They usually occur in the setting of Peutz-Jeghers (PJ) syndrome, which is an autosomal dominant hereditary condition that is associated with mucosal and cutaneous pigmentation around the lips, oral mucosa, face and other parts of the body (Haggitt and Reid, 1986). Histologically, they are composed of arborizing connective tissue with well-developed smooth muscle fibers that extend into the surrounding mucosa and the lamina propria to surround the crypts (Fulcheri et al., 1991). Patients with PJ polyps commonly present with gastrointestinal hemorrhage and anemia, recurrent colicky abdominal pain and sometimes with recurring intussusceptions, especially after a meal in younger patients (Day et al., 2003). Patients with PJ syndrome have a higher risk of developing gastrointestinal and non-gastrointestinal tumors such as breast and ovarian malignancies (Trau et al., 1982).

Inflammatory polyps

These benign polyps can complicate any inflammatory/infectious disease of the gastrointestinal tract and commonly occur in the setting of inflammatory bowel disease (ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease), mucosal ulceration and in the mucosal prolapse syndrome. They can complicate certain infectious conditions of the bowel, for example schistosomiasis and amebiasis (Robertson and Levison, 2006). They are usually multiple and occur as a non-neoplastic proliferation of either mucosa or granulation tissue due to various injuries to colorectal epithelium. Histologically, they are composed of a pedunculated mucosal growth that is composed of inflammation and commonly associated with surface ulceration and granulation tissue formation. They are benign polyps and have no propensity for malignant transformation (Robertson and Levison, 2006).

Benign neoplastic epithelial tumors

Adenomatous polyps

Adenomas are benign neoplastic polyps derived from the surface epithelium and occur in both small and large intestines, involving the latter more frequently (Perzin and Bridge, 1981). Adenomas, by definition, are pre-malignant lesions with increased risk of malignant transformation (Leslie et al., 2002). In the small bowel, most benign adenomas occur in the region of the ampulla of Vater and generally they occur most frequently in the region of the duodenum and jejunum and less frequently in the ileum (Rubin and Isaacson, 1990; Cooperman et al., 1978).

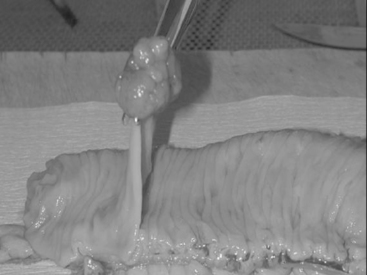

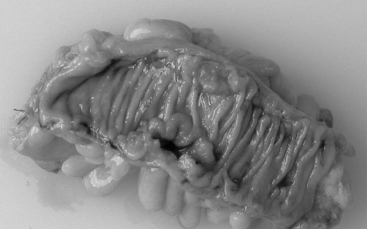

Macroscopically, adenomas can be classified as either sessile or pedunculated. Sessile polyps are attached to the mucosa without a stalk and are usually raised, while peduculated polyps have a stalk (usually composed of normal mucosa) of variable length attached by a narrow base (Figures 14.1 and 14.2) (Robertson and Levison, 2006; Rubin and Strayer, 2007).

Microscopically, they are composed of closely packed and branching glands and can be classified as either tubular, villous or tubulovillous (Geboes et al., 2005). All adenomas, by definition, show disordered cytological differentiation called dysplasia (Geboes et al., 2005; Rubin and Strayer, 2007). Dysplasia is derived from the Greek word, which means ‘dys’ (bad or wrong) and ‘plasis’ (form) (Rubin and Strayer, 2007). Dysplasia in general is defined as ‘unequivocal’, non-invasive neoplastic transformation that is confined within the basement membrane of the glands (Riddell et al., 1983). These changes are pre-neoplastic and can lead to malignant transformation. The cytological features that define dysplasia include nuclear enlargement and hyperchromasia with abnormal chromatin pattern. It also includes nuclear crowding and stratification with increased mitotic figures (Figure 14.3, see color insert) (Riddell et al., 1983). These changes may deviate minimally from normal (low grade dysplasia) or severely from normal (high grade dysplasia). This classification depends upon the histological examination of the degree of cellular immaturity and nuclear features together with the architectural distortion of the glands. Adenomas displaying high-grade epithelial dysplasia have a higher risk of developing adenocarcinoma.

In the large bowel, 40% of adenomatous polyps are found in the right side, 40% in the left side and 20% involve the rectum (Konishi and Morson, 1982) with their frequency rising with age and being uncommon before the age of 30. Most polyps are asymptomatic, but the most common presentation is gastrointestinal bleeding and vague abdominal pain (Sobin, 1985). The risk factors for developing adenomas are the same for colorectal cancer, which include a low fiber and high fat diet and alcohol consumption (Martinez et al., 1996).

The malignant risk of an adenoma if left untreated has been reported to be 2.5%, 8% and 24% after 5, 10 and 20 years. The risk of malignant transformation is very much increased if there is severe dysplasia, villous configuration of the polyp and size over 2 cm (Stryker et al., 1987; Brenner et al., 2007).

Malignant epithelial tumors

Malignant tumors of the small and large intestine can be of epithelial, mesenchymal or lymphoid origin. The most common malignant tumors involving the bowel are of epithelial origin and comprising epithelial derived adenocarcinomas. Adenocarcinoma of the small bowel is 40 to 60 times less common than large bowel carcinoma (Rosai, 2004) with approximately 40–60% occurring in the region of the ampulla of Vater in the duodenum (Rudan et al., 1984).

Colorectal cancer (CRC)

CRC is the third most common cancer and the fourth most frequent cause of cancer deaths worldwide (Robertson and Levison, 2006). At present, in the UK, colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer after breast and lung (Cancer Research UK, 2007). The left side of the colon is affected more than the right and the rectosigmoid junction accounts for over half of all cases (Cancer Research UK, 2007). Eighty-three percent of cases arise in people who are 60 years or older. The disease is more common in North America and Northern Europe and relatively uncommon in Africa (Day et al., 2003). The 5-year survival in developed countries exceeds 60% due to better access to specialist treatment, while it is less than 40% in developing countries (Weitz et al., 2005).

Etiology and risk factors of CRC

Sporadic CRC

Most colorectal cancers are sporadic in which genetic and environmental factors are important in the etiology (Weitz et al., 2005). Some of the risk factors associated with the development of colorectal cancer include older age, male sex, cholecystectomy and hormonal factors in women (nulliparity and early menopause). Some environmental factors are also known to increase the risk of developing colorectal cancer including a diet rich in meat and fat and poor in fiber, folate and calcium (Weitz et al., 2005). Such a diet is associated with slower transit of fecal contents through the colon and permits longer exposure of the mucosa to possibly toxic substances in the stool. There is a close relationship between per capita meat intake and colorectal cancer incidence (Drasar and Irving, 1973). High intake of fruit, vegetables and fiber is associated with reduced risk of developing CRC (Weitz et al., 2005; Wickam and Lassere, 2007).

Other factors are also known to be associated with an increased risk of developing colorectal cancer including obesity, diabetes mellitus, smoking, previous radiation therapy and high alcohol intake (Weitz et al., 2005). People reporting long-term (at least ten years) regular use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or taking at least two tablets a day have a significantly reduced risk of bowel cancer (Chan, 2005).

Colorectal cancer may arise in patients affected by inflammatory bowel disease. This risk depends on the disease duration (at least after 8 years), extent of inflammation, family history of CRC and presence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (Weitz et al., 2005), hence regular surveillance in these patients is recommended for early detection of this complication.

Hereditary CRC

FAP is an autosomal dominant disease with a mutation in the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene on chromosome 5 (Chan, 2005). Patients with FAP can develop hundreds of mucosal adenomatous polyps that carpet the mucosa and, if left untreated, almost all patients develop cancer by the age of 40 (Weitz et al., 2005). These patients can also have adenomatous polyps elsewhere in the bowel, such as the duodenum and the stomach, from which carcinoma can arise (Bulow et al., 2004).

HNPCC (also known as Lynch syndrome) is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by mutation of the mismatch repair genes. Microsatellite (which are short repeated DNA sequences) instability is considered to be the main etiology of the disease (Grady, 2003). Patients with this syndrome also have increased risk of developing tumors elsewhere, such as the genitourinary system particularly of the endometrium, as well as the pancreas and the biliary system. Interestingly, increased risk of developing brain tumors is present with both FAP and HNPCC with medulloblastomas common in the former and gliomas in the latter (Vasen et al., 1996).

Pathology and pathogenesis of colorectal cancer

Almost 95% of colonic tumors are of epithelial origin and arise from the glandular epithelium (Drasar and Irving, 1973; Robertson and Levison, 2006). Adenomatous polyps precede colorectal cancer in 70–90% of patients and 50% of large polyps (more than 2 cm in diameter) become malignant while the risk is smaller with smaller polyps (less than 5 mm) (Drasar and Irving, 1973). Adenomatous polyps are up to six times more common in colonic specimens with cancer (Day et al., 2003).

This strong link between adenomas and colorectal cancer led to the development of the multistep theory of colorectal carcinogenesis. This is a well-documented pathway and involves multistep progression from normal mucosa to dysplastic epithelium to invasive carcinoma (Bulow et al., 2004; Robertson and Levison, 2006; Leslie et al., 2002). This multistep model, developed by Fearon and Vogelstein (1990), involves certain oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes with accumulation of multiple genetic alterations and mutations. Mutations of normal oncogenes inhibit the deregularity effect of these genes and promote cancer growth, whereas mutations in the normal tumor suppressor genes (e.g. p53) inhibit the tumor suppressor activity of these genes and subsequently promote the development of cancer cells (Vasen et al., 1996).

The most common first step in the development of colorectal cancer is the mutation of the adenomatous polyposis coli gene, which leads to cellular deregulation and the development of adenomatous polyps (Drasar and Irving, 1973). The most common next step is the mutation of the K-ras oncogene and deleted in colorectal cancer gene, which leads to an increase in the size of an established adenoma. The final step is the loss or mutation of p53 tumor suppressor gene (Robertson and Levison, 2006) that leads to the development of carcinoma.

Another suggested pathway occurs through microsatellite instability that involves DNA mismatch repair genes. Microsatellites are small regions of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), one to five base pairs long, that are repeated multiple times. They are widely dispersed throughout the genome and are susceptible to errors during DNA replication. In health, the DNA mismatch repair proteins are responsible for correcting replication errors. However, if this repair mechanism is faulty or absent, numerous replication errors remain uncorrected and, if present at a significant level, the term ‘microsatellite instability’ is used. Microsatellite instability is responsible for the development of adenocarcinomas with a predilection for the right side of the colon, poor histological differentiation, but a relatively favorable prognosis (Robertson and Levison, 2006). However, the exact sequence of development of adenocarcinoma is not always known, as colorectal cancers are usually heterogeneous (Syngal et al., 2006).

Adenocarcinoma of the large bowel (Figure 14.4) is more commonly found in the left side of the colon than the right side, in which the rectosigmoid region is involved in approximately 55% of cases and the cecum and ascending colon in 22% of cases (Robertson and Levison, 2006). Right-sided tumors tend to be more polypoidal and present as exophytic masses projecting into the lumen, while left-sided tumors tend to be more circumferential, causing strictures and tumors in this region which are more liable to cause large bowel obstruction.

Histological examination is of utmost importance in establishing the diagnosis of carcinoma. By definition, invasion of malignant glands into the submucosa establishes the diagnosis of carcinoma. Depending on the degree of differentiation, adenocarcinoma can be divided into well, moderate and poorly differentiated depending on the amount of well-formed glands that constitute the tumor and their similarity to the normal epithelium. The degree of differentiation, together with other factors, affects the prognosis of the patient with the disease (Rosai, 2004). Other factors likely to be associated with worse prognosis include very young and very old age, tumor perforation, vascular invasion and lymph node involvement. However, the most influential factor which affects the prognosis of patients with CRC is the stage of the disease, which is the degree of tumor spread or extension.

Several staging systems have been used for colorectal cancer. The most common staging system is the Dukes stage (Table 14.2) (Dukes, 1932). The Dukes stage depends on the depth of tumor invasion and lymph node involvement. The TNM (tumor, node and metastasis) staging system is also used increasingly for colorectal cancers (Table 14.3). The prognosis and hence survival of patients with CRC mainly depends on the stage. For patients with Dukes stage ‘A’ (tumor limited to the wall), the 5-year survival is 95–100% while with Dukes ‘C’ (tumor with lymph node involvement) the prognosis is poor and the 5-year survival is between 10 and 35% (Day et al., 2003; Robertson and Levison, 2006).

| Dukes stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| A | Tumor limited to wall (not beyond muscularis propria), nodes negative |

| B | Tumor invading beyond muscularis propria, nodes negative |

| C | Tumors with metastasis to regional lymph nodes (apical node negative ‘C1’; apical node positive ‘C2’) |

| D | Distant metastases present |

Table 14.3 TNM staging system for CRC

| Tumor | Definition |

|---|---|

| Tx | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ: intraepithelial or invasion into the lamina propria with no extension through muscularis mucosae into submucosa |

| T1 | Tumor invades into submucosa, but not the muscularis propria |

| T2 | Tumor invades into but not through the muscularis propria |

| T3 | Tumor invades through bowel wall into subserosa or non-peritonealized pericolic/perirectal tissues |

| T4 | Tumor invades other organs and structures and/or perforates visceral peritoneum |

| Nodes | |

|---|---|

| Nx | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastases |

| N1 | 1–3 regional lymph node(s) |

| N2 | 4 or more regional lymph nodes |

| Metastases | |

|---|---|

| Mx | Metastatic disease cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No evidence of metastatic disease |

| M1 | Distant metastases present |

Neuro-endocrine tumors

The most common neuro-endocrine tumor is the carcinoid tumor. They arise from the neuro-endocrine cells of the surface mucosal epithelium and can be divided into non-functioning and functioning (Robertson and Levison, 2006). Functioning tumors release peptide hormones such as gastrin, somatostatin and serotonin and they are usually associated with the so-called carcinoid syndrome. The appendix is the commonest site to be involved (Kumar et al., 2004).

Mesenchymal tumors

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are the most common non-epithelial tumors of the gastrointestinal tract and, until recently, they were thought to be of smooth muscle origin. However, recently, it has been demonstrated that they originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal which are the cells involved in the innervation of the gut (Fletcher et al., 2002). Macroscopically, these are usually well-circumscribed tumors, exophytic and protruding into the lumen of the gut with frequent surface ulceration. They most commonly occur in the stomach (approximately 60%) and approximately 25–40% arise in the small bowel. These tumors can be divided into benign, malignant and of indeterminate behavior according to the tumor size, number of mitoses and the presence or absence of cellular atypia. These tumors contain a protein, which is usually detected on immunohistochemistry (CD117). This finding has a therapeutic benefit to patients because these patients are usually responsive to the drug Imatinib (Robertson and Levison, 2006).

Lipomas

These are benign tumors of fatty tissue and are infrequently found to involve the intestine. However, they can arise near the area of the ileocecal valve within the submucosa causing narrowing of the lumen and, in some cases, obstruction (Robertson and Levison, 2006). Liposarcomas, the malignant counterparts of lipomas rarely involve the small and large intestine.

Angiomas

Angiomas are benign tumors of vascular origin and are infrequently found within the gastrointestinal tract. Histologically, they can appear as either a cavernous or capillary hemangioma and they can sometimes bleed and lead to melena and anemia (Robertson and Levison, 2006).

Lymphomas

These are of lymphoid origin and are more common in the small bowel than the large bowel. It is one of the commonest tumors to involve the small bowel and accounts for 17% of tumors at this site, whereas it accounts for only 0.2% of tumors of the large bowel. Most intestinal lymphomas are of B-cell non-Hodgkin’s type, but T-cell type also occurs and these are commonly associated with and complicate celiac disease (Rooney and Dogan, 2004), termed enteropathy associated T-cell lymphoma.

Glossary

Benign tumors tumors which grow slowly and are usually treatable (by surgery) and are not life threatening.

Dysplasia is an abnormal growth and differentiation of cells where the cells grow in a disordered manner with abnormal maturation. It is a pre-neoplastic process.

Epithelium the covering of the internal and external organs of the body and also the lining of vessels, body cavities, glands and organs.

Hamartoma a hamartoma is a peculiar benign neoplasm, which is a localized but haphazard growth of tissues normally found at a given site (pulmonary hamartoma has jumbled cartilage, bronchial epithelium and connective tissue).

Hyperplasia is an increase in the size of a tissue or organ due to an increase in the number of constituent cells. It is not considered to be a pre-neoplastic process.

Malignant tumors they grow fast and are liable to metastasize to distant body sites and are usually life-threatening neoplasms.

Mesenchymal tumors they are connective tissue tumors such as fibromas, lipomas or osteomas and their malignant counterparts.

Microsatellite microsatellites are small regions of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA), one to five base pairs long, that are repeated multiple times.

Neoplasm (tumor) is an abnormal mass of tissue, the growth of which exceeds and is uncoordinated with that of normal tissue and persists in the same excessive way after cessation of the stimuli which evoke the change.

Brenner H., Hoffmeister M., Stegmaier C., et al. Risk of progression of advanced adenomas to colorectal cancer by age and sex: estimates based on 840 149 screening colonoscopies. Gut. 2007;56(11):1585-1589.

Bulow S., Bjork J., Christensen I., et al. Duodenal adenomatosis in familial adenomatous polyposis. Gut. 2004;53(3):381-386.

Cancer Research UK. Colorectal cancer statistics. 2007. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org [Accessed: 10 August, 2007]

Chan A. Long-term use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of colorectal cancer. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2005;294(8):914-923.

Day D., Jass J., Price A., et al. Morson and Dawson’s gastrointestinal pathology, fourth ed. Blackwell Publishing, 2003.

Drasar B., Irving D. Environmental factors and cancer of the colon and breast. Br. J. Cancer. 1973;27(2):167-172.

Dukes C. The classification of cancer of the rectum. J. Pathol. Bacteriol.. 1932;35:323-332.

Fearon E., Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell. 1990;61(5):759-767.

Fletcher C., Berman J., Corless C., et al. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum. Pathol.. 2002;33(5):459-465.

Fulcheri E., Baracchini P., Pagani A., et al. Significance of the smooth muscle cell component in Peutz-Jeghers and juvenile polyps. Hum. Pathol.. 1991;22(11):1136-1140.

Geboes K., Ectors N., Geboes K. Pathology of early lower GI cancer. Best Prac. Research Clin. Gastroenterol. 2005;19(6):963-978.

Grady W. Genetic testing for high-risk colon cancer patients. Gastroenterology. 2003;124(6):1574-1594.

Haggitt R., Reid B. Hereditary gastrointestinal polyposis syndromes. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.. 1986;10(12):871-887.

Konishi F., Morson B. Pathology of colorectal adenomas: a colonoscopic survey. J. Clin. Pathol.. 1982;35(8):830-841.

Kumar V., Abbas A., Fausto N. Robbins and Cotrans’ pathologic basis of disease, seventh ed. Saunders, 2004.

Leggett B., Devereaux B., Biden K., et al. Hyperplastic polyposis: association with colorectal cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.. 2001;25(2):177-184.

Leslie A., Carey F., Pratt N., et al. The colorectal adenoma-carcinoma sequence. Br. J. Surg.. 2002;89(7):845-860.

Longacre T., Fenoglio-Preiser C. Mixed hyperplastic adenomatous polyps/serrated adenomas. A distinct form of colorectal neoplasia. Am. J. Surg. Pathol.. 1990;14(6):524-537.

Martinez M., McPherson R., Annegers J., et al. Association of diet and colorectal adenomatous polyps: dietary fiber, calcium, and total fat. Epidemiology. 1996;7(3):264-268.

Nugent K., Talbot I., Hodgson S., et al. Solitary juvenile polyps: not a marker for subsequent malignancy. Gastroenterology. 1993;105(3):698-700.

Perzin K., Bridge M. Adenomas of the small intestine: a clinicopathologic review of 51 cases and a study of their relationship to carcinoma. Cancer. 1981;48(3):799-819.

Riddell R., Goldman H., Ransohoff D., et al. Dysplasia in inflammatory bowel disease: standardized classification with provisional clinical applications. Hum. Pathol.. 1983;14(11):931-968.

Robertson K., Levison D. Pathology of tumours of the small and large intestine. Surgery. 2006;24(4):126-131.

Rooney N., Dogan A. Gastrointestinal lymphoma. Curr. Diag. Pathol. 2004;10:69-78.

Rosai J. Rosai and Ackerman’s surgical pathology, Ninth ed. Mosby, 2004.

Rubin A., Isaacson P. Florid reactive lymphoid hyperplasia of the terminal ileum in adults: a condition bearing a close resemblance to low-grade malignant lymphoma. Histopathology. 1990;17(1):19-26.

Rubin R., Strayer D. Rubin’s pathology: clinicopathologic foundations of medicine, fifth ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007.

Rudan N., Nola P., Popovic S. Primary adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. Report of two cases. Cancer. 1984;54(6):1105-1109.

Sobin L. The histopathology of bleeding from polyps and carcinomas of the large intestine. Cancer. 1985;55(3):577-581.

Stryker S., Wolff B., Culp C., et al. Natural history of untreated colonic polyps. Gastroenterology. 1987;93(5):1009-1013.

Syngal S., Stoffel E., Chung D., et al. Detection of stool DNA mutations before and after treatment of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer. 2006;106(2):277-283.

Trau H., Schewach-Millet M., Fisher B., et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome and bilateral breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1982;50(4):788-792.

Vasen H., Sanders E., Taal B., et al. The risk of brain tumours in hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC). Int. J. Cancer. 1996;65(4):422-425.

Weitz J., Koch M., Debus J., et al. Colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2005;365(9454):153-165.

Wickam R., Lassere Y. The ABCs of colorectal cancer. Semin. Oncol. Nurs.. 2007;23:1-8.

Williams G., Arthur J., Bussey H., et al. Metaplastic polyps and polyposis of the colorectum. Histopathology. 1980;4(2):155-170.