Tuboplasty

The oviducts may be obstructed principally at three locations: (1) at the cornua; (2) at the fimbriated end; and (3) at any point between these two locations. The causes of oviductal obstruction are myriad and include infection, ectopic pregnancy, endometriosis, intentional tubal ligation, and partial salpingectomy. Before surgery is performed, a thorough diagnostic survey should be done, including laparoscopy, chromotubation, and hysterosalpingography. Several of the techniques described here can be performed by laparoscopy, laparotomy, or microsurgery. Similarly, the incisional portions of these procedures may be performed with conventional mechanical devices, superpulsed carbon dioxide (CO2) lasers, or electrosurgical tools. The author prefers to utilize a variety of instruments, basing selection on the circumstances of the pathology and the relative advantages of a particular device for a specific circumstance. These surgical techniques use fine instruments, gentle tissue manipulation, small-gauge suture material, and needles. Compulsive hemostasis is required for successful outcomes.

Fimbrioplasty (Hydrosalpinx)

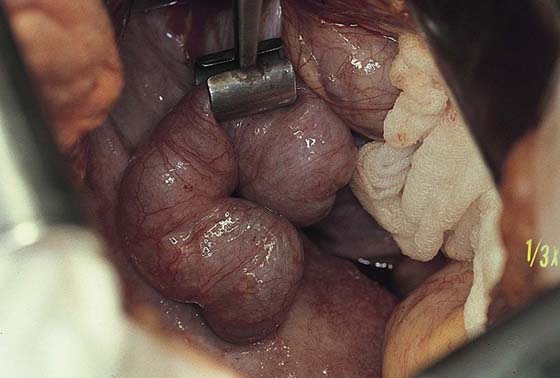

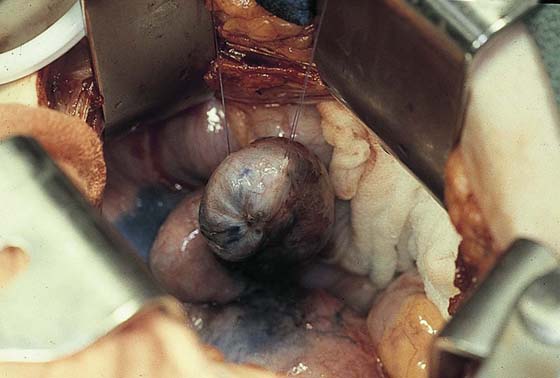

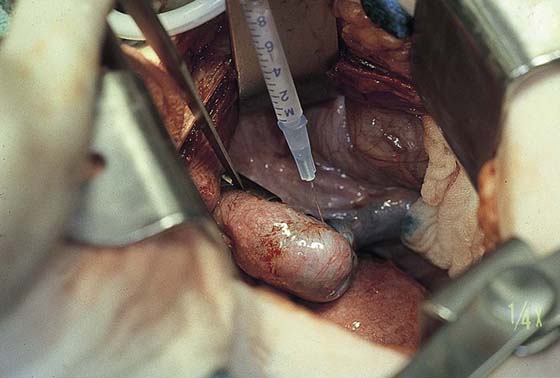

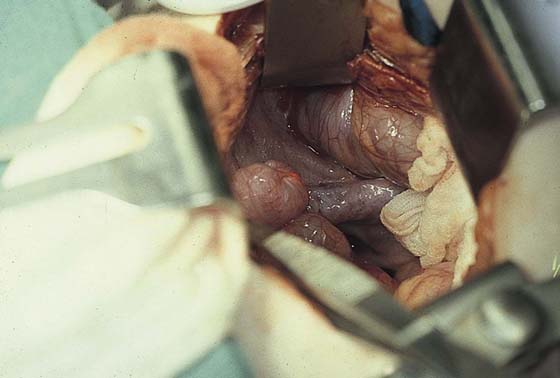

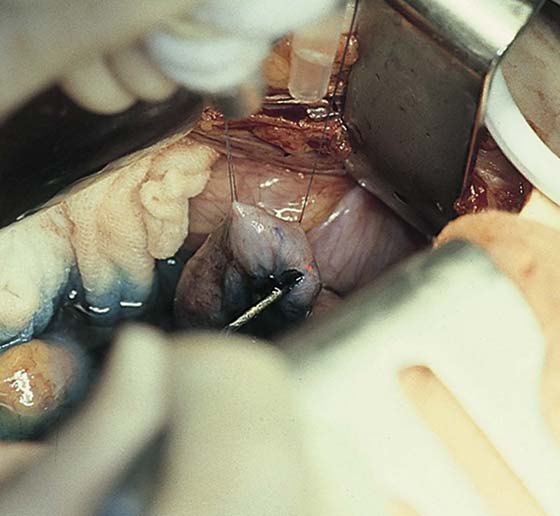

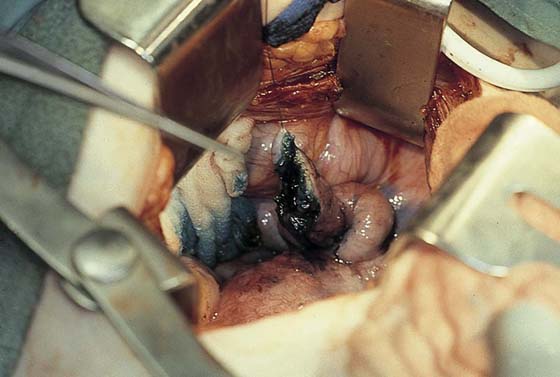

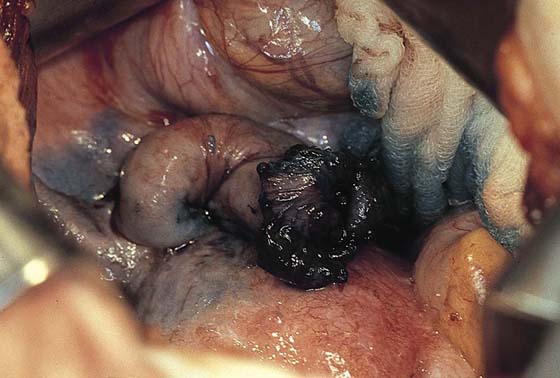

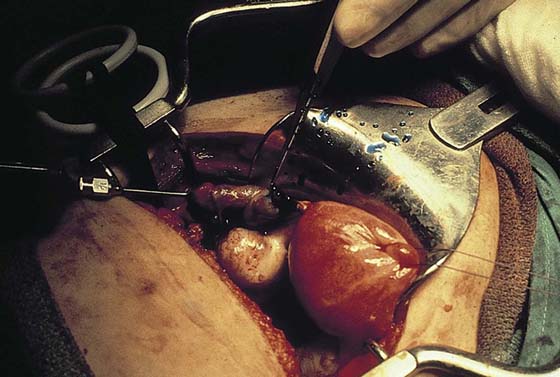

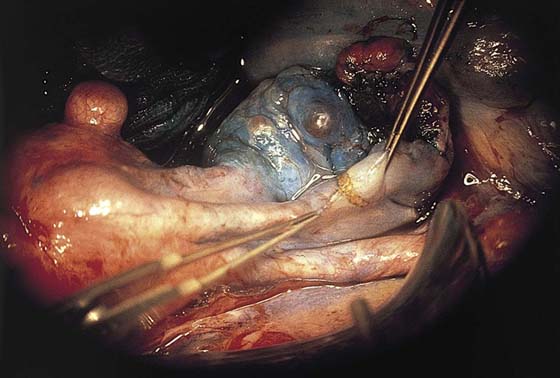

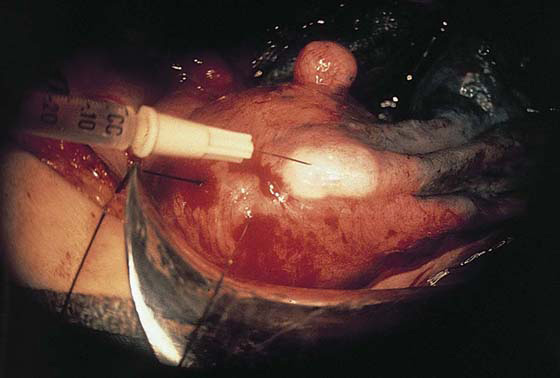

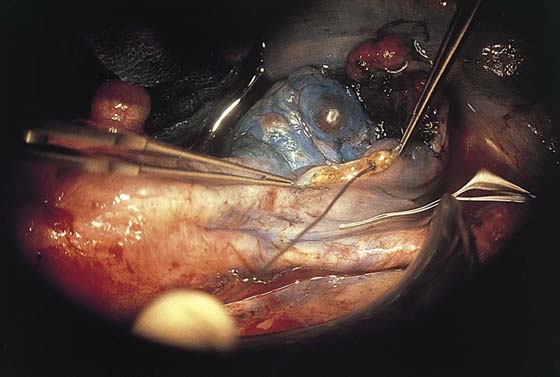

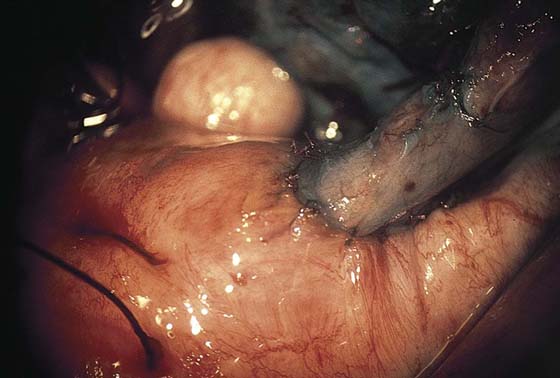

A hydrosalpinx connotes a damaged tube (Fig. 29–1). Methylene blue dye should be injected transcervically to determine whether the tube fills. If the tube distends with the dye, then a fimbrioplasty may be attempted (Fig. 29–2). Traction sutures of 4-0 Vicryl are placed to permit gentle tissue manipulation and to obtain good stability of the oviduct during surgery (Fig. 29–3). A CO2 superpulsed laser (Lumenis, Santa Clara, California) set at 12 W at 300 pulses/sec is focused to deliver a 1-mm-diameter spot (Fig. 29–4). A hole is drilled into the central point of the fimbrial adhesion (Fig. 29–5). Blue dye spews forth as the oviductal canal is entered. A lacrimal probe is inserted into the opening. Four radial cuts are made from the central point and are carried into the tubal lumen (Fig. 29–6). These may range from 3 to 10 mm in length.

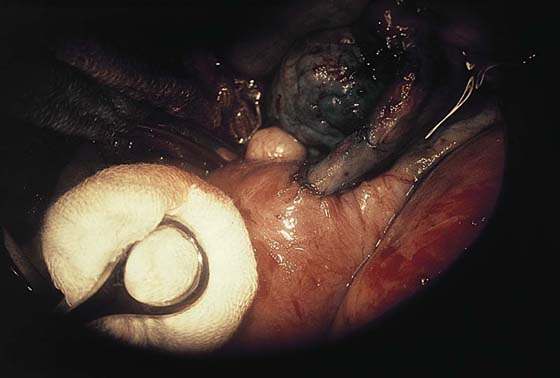

The edges of each radial cut are then sutured back to the tubal serosa or are laser brushed to create a cuff (Fig. 29–7). The preferred suture material is 5-0 polydioxanone (PDS)/Vicryl. The cuff exposes to the ovary a large surface area of tubal ciliated cells. Patency is again checked by retrograde injection of methylene blue dye (Fig. 29–8).

FIGURE 29–1 The distended oviduct is secured for inspection with a tube clamp. This figure demonstrates a classic hydrosalpinx.

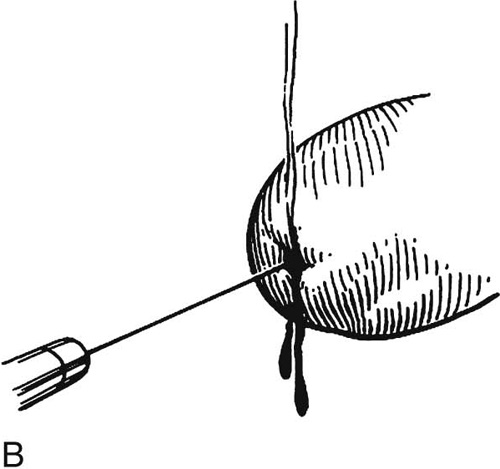

FIGURE 29–2 The oviduct is filled with methylene blue injected retrogradely through a transcervical Cohen-Eder cannula.

FIGURE 29–3 A 1 : 200 solution of vasopressin is injected into the planned operative site with a 25-gauge needle.

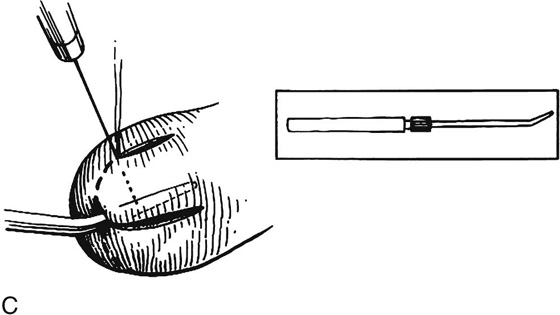

FIGURE 29–4 The helium-neon aiming beam of a carbon dioxide (CO2) superpulsed laser is aimed at the dimple in the fimbriated end of the hydrosalpinx. This represents the site of central agglutination of the fimbria.

FIGURE 29–5 Entry into the tubal lumen is signified by the leakage of methylene blue–tinged fluid. A metal probe is inserted into the lumen.

FIGURE 29–6 The tube is opened widely by cutting four flaps.

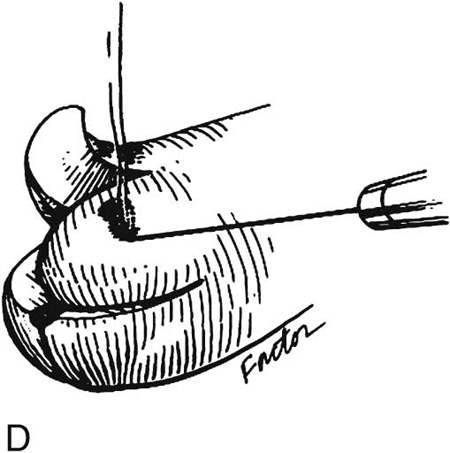

FIGURE 29–7 The flaps are sutured back through the tubal serosa, creating an open cuff.

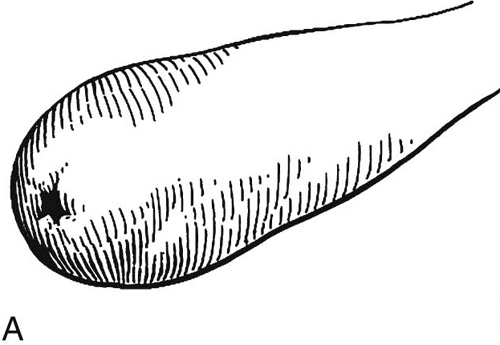

FIGURE 29–8 The entire process is illustrated schematically. Instead of suturing the flaps, a cuff is created by lasering the flap serosa at low power (brushing), thus creating a slow, mild serosal coagulation and resultant retraction of the tubal mucosa.

Midtubal Anastomosis

Midtubal obstruction (e.g., as produced by previous tubal ligation) may be treated by segmental resection followed by anastomosis over a stent.

Methylene blue dye is injected retrogradely, filling the nonoccluded portion of the distal (uterine end) oviduct (Fig. 29–9). A 1 : 200 solution of vasopressin is then injected just beyond the obstruction (Fig. 29–10). The tube is cut with a scalpel to the level of the mesosalpinx (i.e., a circumferential cross-sectional cut). Blue dye emits from the opened lumen of the oviduct. A fine probe is inserted in the direction of the uterine cavity. Four 5-0 Vicryl sutures are placed clockwise, full thickness through the cut edge of the tube, and are held with mosquito clamps.

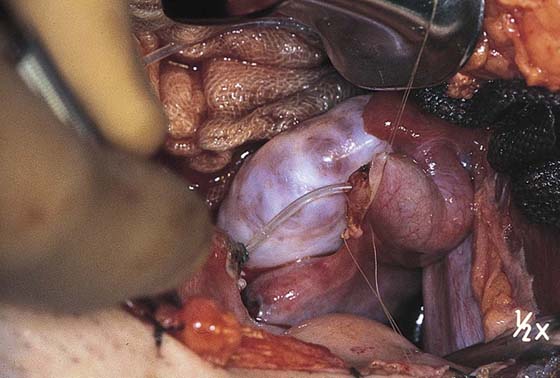

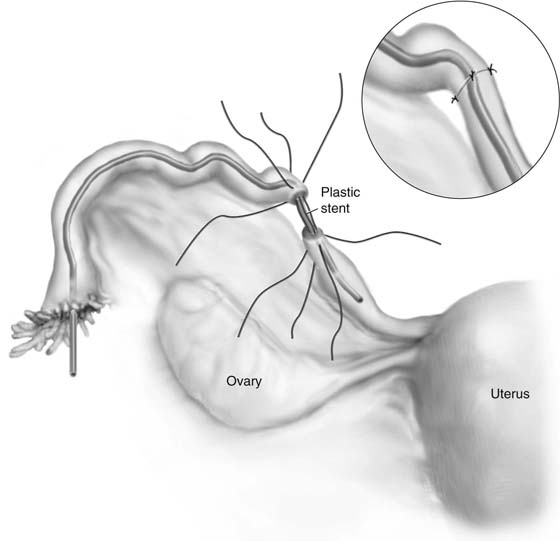

Attention is drawn to the fimbriated end of the tube. A probe is placed through the fimbria and is advanced until it meets the obstruction (Fig. 29–11). This marks the point where the scar tissue begins. A 1 : 200 vasopressin solution is injected into the tube at this point. The knife cuts the oviduct as mentioned earlier until the tip of the probe is exposed (see Fig. 29–11). The obstructed segment is cut away and the mesosalpinx sutured with a 4-0 Vicryl running lock stitch. A fine plastic or Silastic tube is threaded through the newly opened oviduct (Fig. 29–12). Care should be taken to avoid kinking the tube. The previous stitches (placed from outside in) are now taken up and sutured into the proximal segment through an inside-out technique (Fig. 29–13). The four stitches may now be tied over the stent. If additional stitches are desired, they should be placed before the original four sutures are secured.

The distal end of the stent tube is fed into the uterine cavity. All suture lines are thoroughly irrigated. The portion of the stent exiting the fimbria should be trimmed (Fig. 29–14).

FIGURE 29–9 Methylene blue dye injected transcervically distends the distal oviduct to the point of ampullary obstruction.

FIGURE 29–10 The tube is manipulated with polyethylene tubing placed through the mesosalpinx. A 1 : 200 vasopressin solution is injected into the distal oviduct at the point of the obstruction.

FIGURE 29–11 A cannula is fed through the fimbria to the point of proximal obstruction. As the obstructed area is cut away, blue dye spills forth.

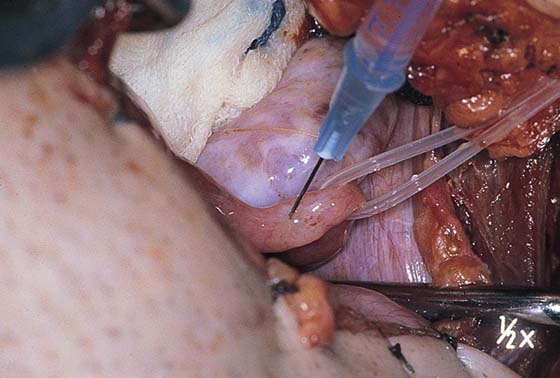

FIGURE 29–12 The proximal (fimbriated) and distal (uterine) patent segments of the oviduct are cannulated with polyethylene tubing, which acts as a stent to facilitate the anastomosis.

FIGURE 29–13 Fine Vicryl (5-0) sutures are placed full thickness into the oviduct, with care taken to avoid stitching the stent. Entry into one tubal segment extends from serosa to mucosa. The other segment is sutured from inside (mucosa) out (serosa). The stitches are tied on the serosa and cut on the knot.

FIGURE 29–14 The tube has been anastomosed and has been demonstrated to be open. The 5-0 Vicryl sutures are barely visible. It is obvious that this anastomosis has been performed with the use of the operating microscope.

Cornual Anastomosis

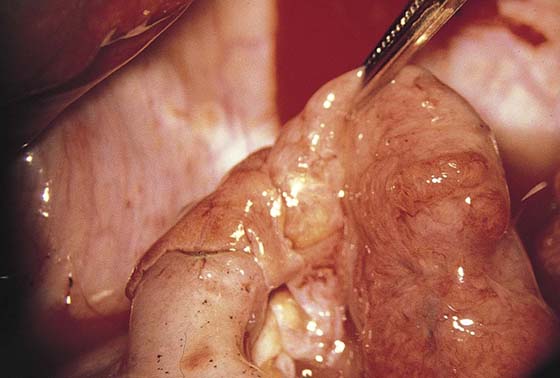

The fimbriated end of the tube is probed by means of a polyethylene cannula inserted into the tube. Dye (methylene blue) is injected. The tube is injected with 1 : 200 vasopressin and is cut just proximal to the obstruction. All bleeding points are secured. The remaining obstructed segment of tube is excised and the mesosalpinx suture-ligated with 3-0 Vicryl (Fig. 29–15).

The cornual portion of the uterus is injected with 1 : 200 vasopressin (Fig. 29–16). Serial sharp cuts are made into the cornua (Fig. 29–17). At the same time, methylene blue is injected retrogradely through the cervix. When the open portion of the interstitial portion of the oviduct is transected, blue dye squirts forth. A lacrimal probe is inserted into the interstitial tube lumen and is advanced into the uterine cavity. The probe is withdrawn, and the polyethylene stent described earlier is fed through the distal tube lumen into the uterine cavity (Fig. 29–18).

Anastomosis of the two segments of tube is carried out with 5-0 or 6-0 Vicryl interrupted sutures (Fig. 29–19). The serosal portion of the oviduct then is anchored to the uterine serosa with 5-0 Vicryl. The cornual defect is closed simultaneously with 4-0 Vicryl (Fig. 29–20).

The abdomen is thoroughly irrigated before closure is performed. The stent is recovered via hysteroscopy 3 to 4 weeks postoperatively.

FIGURE 29–15 The proximal tube has been injected via fimbrial cannulation to demonstrate the area of obstruction. The tube will be cut open at the scored area. The entire segment of cornual and isthmic oviduct is obstructed.

FIGURE 29–16 A 1 : 200 vasopressin solution is injected into the cornua with a fine (25-gauge) needle.

FIGURE 29–17 The cornua is serially sliced until the transcervically injected methylene blue dye flows freely from the opened interstitial portion of the tube.

FIGURE 29–18 The two open ends of the oviduct are approximated at the cornua after the obstructed segment is removed.

FIGURE 29–19 The tube is anastomosed into the cornua in a two-layered closure.

FIGURE 29–20 The cornual incision is closed with 4-0 Vicryl. The serosa of the tube is sutured to the serosa of the uterus with 5-0 Vicryl.