200 Tuberous sclerosis (Bourneville’s or Pringle’s disease)

Salient features

Examination

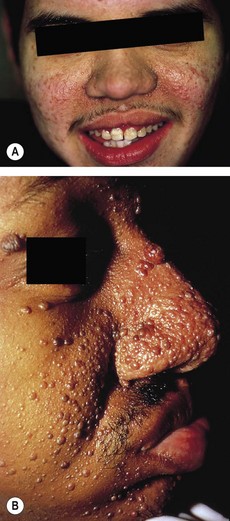

• Angiofibromas (adenoma sebaceum) distributed in a butterfly pattern over the cheeks (Fig. 200.1), chin and forehead

• Shagreen patches: leathery thickenings in localized patches over the lumbosacral region

• Ash-leaf patches: hypopigmented areas (Fig. 200.2)

Advanced-level questions

Give some examples of the appearance of clinical manifestations at distinct developmental points

• Hypopigmented macules (formerly known as ash-leaf spots) are usually detected in infancy or early childhood.

• Shagreen patch is identified with increasing frequency after the age of 5 years.

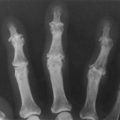

• Ungual fibromas characteristically appear after puberty and may develop in adulthood.

• Facial angiofibromas (formerly called adenoma sebaceum) may be detected at any age but are generally more common in late childhood or adolescence.

• Cortical tubers and cardiac rhabdomyomas form are typical findings in infancy because they form during embryogenesis.

• A subependymal giant cell tumour of the brain may develop in childhood or adolescence.

• Renal cysts can be detected in infancy or early childhood.

• Angiomyolipomas develop in childhood, adolescence or adulthood.

• Pulmonary lymphangiomyomatosis is found in adolescent girls or women

How would you manage such patients?

• Symptomatically, with anticonvulsant therapy for seizures and genetic counselling. When severe epilepsy and mental retardation is present, the prognosis for life beyond the third decade is poor. Death is usually from seizures, associated neoplasms or intercurrent illness.

• Long-term follow-up includes the monitoring of lesion growth. No conclusive guidelines for surveillance have been established. The growth of angiomyolipomas or subependymal giant cell tumours requires regular follow-up. Periodic imaging of the brain and abdomen to monitor the growth of lesions in the brain and kidney should occur at least every 3 years and more often in patients with lesions that have progressive growth. Annual MRI of the brain is suggested until patients are at least 21 years of age, and then MRI should be done every 2 to 3 years both to diagnose and to monitor subependymal giant cell tumours. Annual ultrasonography, MRI or CT is indicated in patients with multiple angiomyolipomas or a single lesion that is progressive.

• Lymphangiomyomatosis: yearly pulmonary function testing may be useful to monitor lung function; some patients may require more frequent assessments.

• Electroencephalography can determine background cerebral activity and characterize patterns such as hypsarrhythmia in infantile spasms.

• Regular dermatologic evaluation is required since facial angiofibromas can cause cosmetic disfiguration and ultimately the lesions will require laser therapy or surgical removal.

Are you aware of any therapies currently being evaluated?

• The discovery of upregulation of the ‘mammalian target of rapamycin’ (mTOR) pathway in tumours associated with tuberous sclerosis presents new possibilities for therapy. Interferon-γ and interferon-α interact with mTOR, leading to deactivation of the translational repressor 4E-BP1, which could be beneficial for therapy.

• Sirolimus therapy causes the dysregulated mTOR pathway to return to normal in cells that lack hamartin or tuberin (encoded by the genes TSC1 or TSC2, respectively). Sirolimus is effective in diminishing the volume of lesions in patients with renal angiomyolipomas, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and sporadic lymphangio leiomyomatosis. However, angiomyolipomas increased in volume after the sirolimus was discontinued, and some patients taking sirolimus experienced serious adverse events. Another concern is that sirolimus therapy may restore the cell’s ability to activate AKT, suggesting that long-term treatment may increase the risk of malignant tumours in these patients.

• Genetic counselling should be recommended to patients to aid with family planning. It is an autosomal dominant disorder; therefore, those affected should be advised that the risk of having an affected child is approximately 50%