Chapter 31 Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections

Tuberculosis

Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathogenesis

Epidemiology

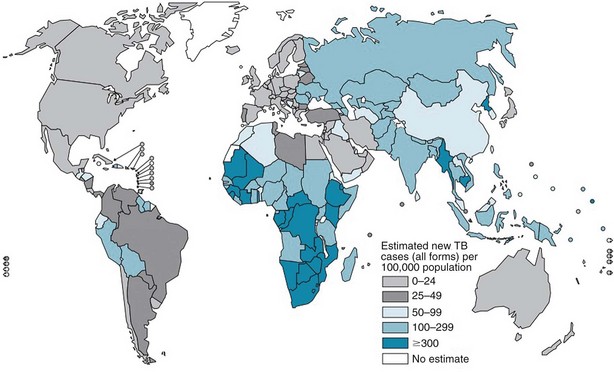

The burden of TB varies significantly throughout the world, with more than 90% of cases occurring among people residing in developing countries (Figure 31-1). The highest incidence rates for TB are in sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in the southern region of the continent. Not surprisingly, the highest prevalence of HIV co-infection also is in this region. Worldwide, approximately 23% of all persons with TB have underlying HIV co-infection; however, in sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 50% of persons with TB have HIV/AIDS.

Risk Factors

Certain people are at higher risk for development of TB simply because they are more likely to be exposed to and thus infected with M. tuberculosis (Table 31-1). For example, approximately 60% of reported TB cases in the United States occur among foreign-born people who come from areas where the disease is endemic. Other populations with an increased prevalence of TB infection include certain racial and ethnic groups, low-income populations, the homeless, and injection drug users.

Table 31-1 Criteria for a Positive Reaction on Tuberculin Skin Testing

| Induration Size | Risk Groups |

|---|---|

| ≥5 mm |

Foreign-born persons recently arrived (<5 years) from high-prevalence countries

Medical conditions† that increase the risk of tuberculosis

Medically underserved, low-income populations (e.g., homeless persons)

Residents and staff of long-term care facilities (e.g., nursing homes, correctional institutions, homeless shelters)

Tuberculin skin test converters (increase of ≥10 mm induration within a 2-year period)

* The predominant chest radiographic finding consistent with previous tuberculosis is presence of fibrotic lesions; other changes such as pleural thickening or isolated calcified granulomas are not related.

† Medical conditions and factors associated with increased risk for development of active disease in a patient with latent tuberculosis infection include silicosis, end-stage renal disease, malnutrition, diabetes mellitus, carcinoma of the head or neck and lung, immunosuppressive therapy, lymphoma, leukemia, weight loss of more than 10% ideal body weight, gastrectomy, and jejunoileal bypass.

Anyone infected with M. tuberculosis can develop TB disease, but certain groups are at higher-than-normal risk for progression to active disease (see Table 31-1). Patients who have been recently infected with M. tuberculosis and those with medical conditions associated with significant immunosuppression are at particularly high risk for development of TB. HIV co-infection is the strongest known risk factor for the development of TB and is estimated to increase the risk of progression to TB by 50- to 100-fold. Inhibitors of tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) may increase the risk for development of TB by up to 10-fold, and patients taking TNF-α blockers frequently present with disseminated disease. This association appears to be stronger for infliximab and adalimumab than for etanercept. Other medical conditions are associated with a more modest increase in risk for development of disease.

Pathogenesis

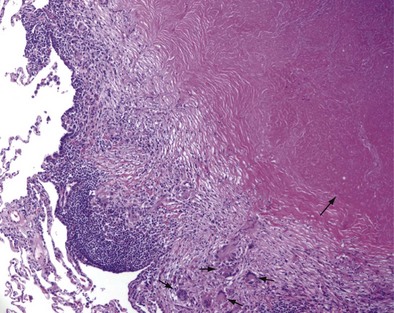

Once cell-mediated immunity develops, collections of activated T cells and macrophages form granulomas that wall off the mycobacterial organisms (Figure 31-2). For most persons with normal immune function, infection with M. tuberculosis seems to be arrested once cell-mediated immunity develops, even though small numbers of viable bacilli remain within the granuloma. Although a primary complex can sometimes be seen on chest radiograph, most TB infections are asymptomatic and can be detected only indirectly with a tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-γ release assay (IGRA). Persons with “walled-off” TB infection who do not have active disease are not infectious and thus cannot spread the disease to others.

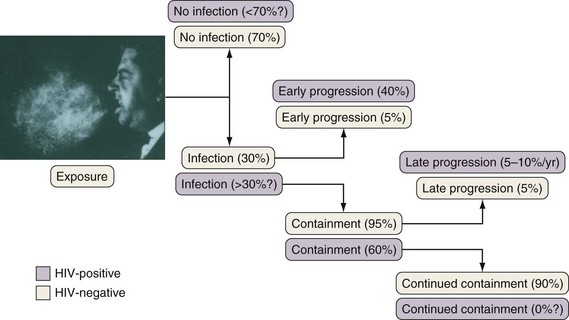

If cell-mediated immunity does not contain the tubercle bacilli, the initial infection progresses to active disease. Without treatment, infected persons have approximately a 5% chance of developing TB in the first 1 to 2 years after infection and an additional 5% chance of developing TB during the remainder of their lifetime (Figure 31-3). By contrast, persons who are co-infected with HIV have a 5% to 10% annual risk of active disease developing. When active TB develops soon after infection, the disease is referred to as primary TB. By contrast, when TB develops years or even decades after the initial infection, the disease is referred to as postprimary or reactivation disease. Exogenous reinfection, involving acquisition of a second strain of M. tuberculosis, also can lead to disease and seems to be more common in HIV-infected patients.

Clinical Features

Pulmonary Tuberculosis

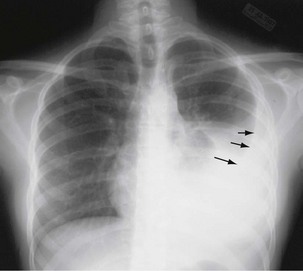

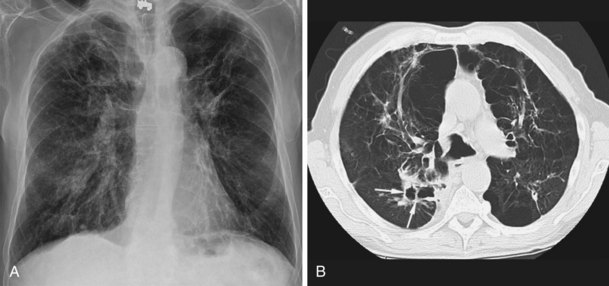

The initial infection in the lung, referred to as primary infection, causes formation of an inflammatory infiltrate, which may be seen on a chest radiograph, often in the middle or lower lung zones. The draining lymph nodes may enlarge and compress adjacent bronchi, particularly in infants and children. Parenchymal disease usually clears as cell-mediated immunity develops, and it tends to clear more rapidly than nodal involvement. If the parenchymal disease persists beyond the development of cell-mediated immunity, cavitation may occur, although this finding is uncommon. Pleural effusions are a common manifestation of primary TB and presumably result when a peripheral, caseous focus ruptures into the pleural space (Figure 31-4). Pleuritis caused by TB may manifest as an acute illness characterized by cough, fever, and pleuritic chest pain.

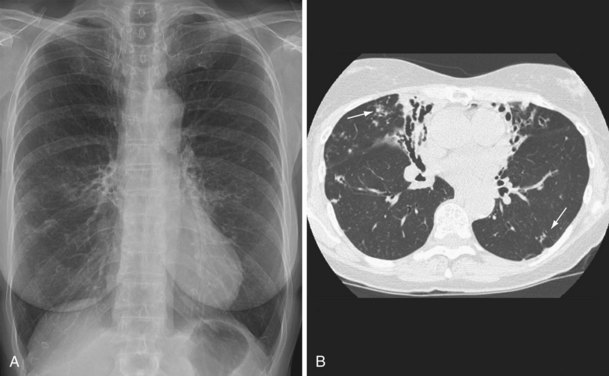

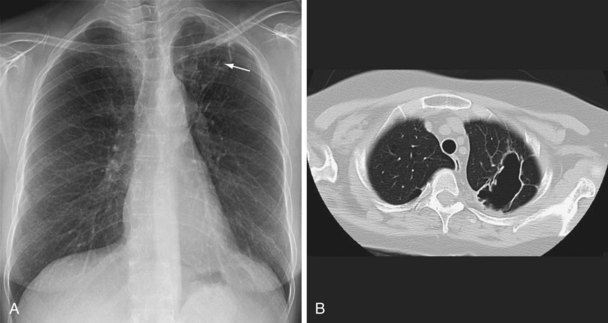

During most initial infections with M. tuberculosis, small numbers of organisms are disseminated hematogenously, and some become seeded in the apices of the lung. The organisms seem to grow preferentially in this well-oxygenated environment, with progression to active disease occurring months or years after the initial infection. This accounts for the characteristic radiographic location of reactivation disease, which in most cases occurs in the apical or posterior segments of the upper lobes (Figure 31-5). In areas of chronic infection or areas of caseation, fibrosis may occur. Fibrocaseous lesions may contain live mycobacteria for many years, and these are the lesions that may reactivate years later.

Miliary Tuberculosis

Miliary or disseminated TB occurs when tubercle bacilli spread throughout the body, through the bloodstream, resulting in small (approximately 1 to 2 mm) granulomatous lesions. Miliary TB is seen more commonly in infants, children less than 4 years old, and in immunocompromised people. Disease can result from early dissemination after infection or later after reactivation and dissemination. Disseminated TB usually develops insidiously with systemic symptoms such as fever, weakness, weight loss, fatigue, and anorexia. Cough and dyspnea also may be prominent symptoms. The mean duration of symptoms approaches 16 weeks, but some patients may go undiagnosed for more than 2 years. The chest radiograph typically shows the classic “miliary” pattern of diffuse small nodules (Figure 31-6). Sputum AFB smears are positive in 20% to 25% of cases, and sputum is culture-positive for M. tuberculosis in up to 65% of cases. Bronchoscopy should be considered in patients who are unable to produce sputum or who have produced negative sputum smears. Other potential sources include urine, which is culture-positive in up to 25% of patients, and liver and bone marrow, which are culture-positive in up to 25% to 40%.

Diagnosis

To diagnose TB, the disease must first be suspected. TB should be suspected in certain high-risk groups reviewed previously (see Table 31-1) and when the clinical and/or radiographic presentation is consistent with TB. The medical history should elicit whether or not the person suspected of having TB has been exposed to M. tuberculosis or has a previous history of TB infection or disease. Symptoms at presentation will vary depending on the sites(s) of involvement and extent of disease as described previously. Guidelines suggest that all persons with an unexplained cough lasting 2 to 3 weeks or more be evaluated for TB. Of note, up to 20% of patients with pulmonary disease are asymptomatic. Findings at physical examination are rather nonspecific and will vary, depending on the site of involvement. Among HIV-infected patients, TB should be considered when any respiratory infection or fever of unknown origin occurs, because the risk for TB in this group is substantially elevated, and signs and symptoms of TB often are atypical.

Radiographic Examinations

Plain chest radiography is a sensitive but nonspecific test to detect pulmonary TB. Radiographic manifestations of TB vary, depending on whether the patient has primary or postprimary TB and whether co-infection with HIV is present. Patients who have primary pulmonary TB at initial evaluation may demonstrate radiographic opacities in the lower lung zones and an associated pleural effusion (see Figure 31-4). TB caused by reactivation typically involves the apical and posterior segments of the upper lobes or superior segment of the lower lobe (see Figure 31-5). Cavitation and volume loss are common in reactivation disease but unusual in primary disease. Findings on the chest radiograph in patients co-infected with HIV depend on the severity of immunosuppression. Early in the course of HIV disease, the radiograph may show a typical reactivation pattern with cavitation (Figure 31-7), but as the CD4+ cell count declines, the radiographic appearance is more like the pattern seen in primary TB (Figure 31-8). Patients co-infected with HIV may sometimes have a normal-appearing chest radiograph despite being sputum AFB smear–positive.

Bacteriologic Examination

Sputum Microscopy

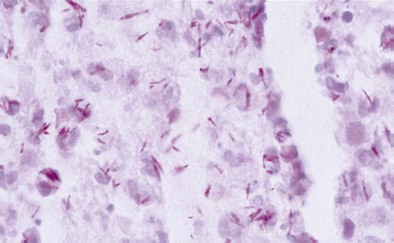

Diagnosis of pulmonary TB begins with obtaining two or three spontaneously expectorated sputum samples collected at 8- to 24-hour intervals, with at least one collected in early morning. Two methods are commonly used for acid-fast staining: the carbolfuchsin methods (Ziehl-Neelsen and Kinyoun methods) and a fluorochrome procedure that uses auramine O or auramine-rhodamine dyes (Figure 31-9).

Treatment

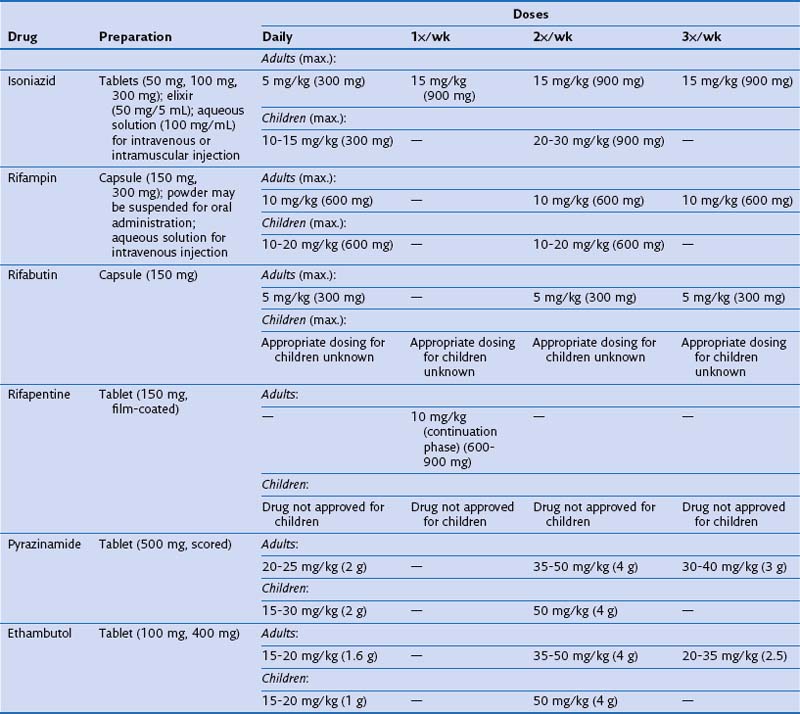

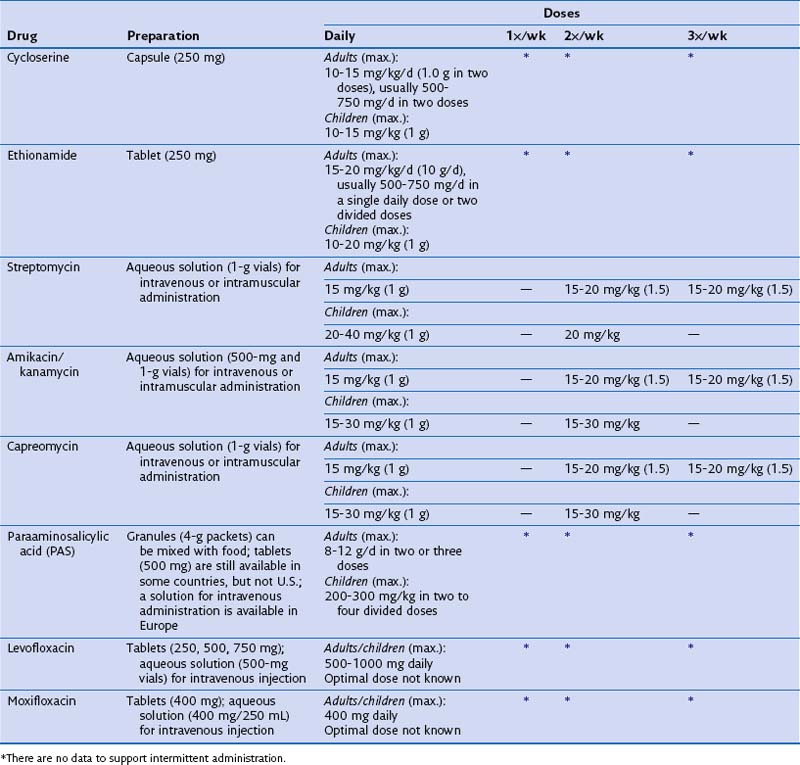

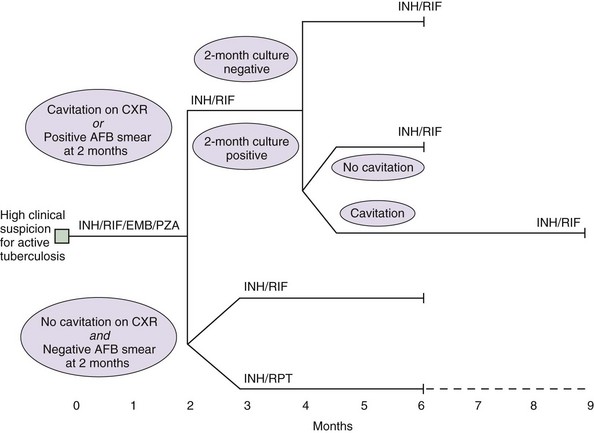

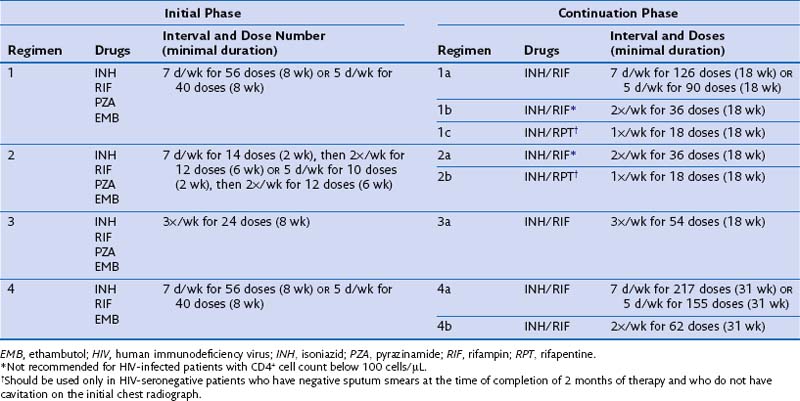

Identifying and treating patients with TB is the most effective way of preventing transmission in the community. TB must be treated with at least two drugs to which the organism is susceptible, to prevent the emergence of drug resistance. Dosages of commonly used first-line and second-line drugs are shown in Tables 31-2 and Table 31-3, respectively. In the United States, a regimen consisting of INH and rifampin given for 6 months, plus pyrazinamide for the initial 2 months, is considered standard short-course therapy. Ethambutol should be added to the treatment regimen for the first 2 months of therapy, but once a drug-susceptible isolate has been demonstrated, ethambutol can be stopped (Table 31-4). After the first 2 months of treatment, one of several regimens can be chosen for the continuation phase of treatment. For HIV-negative patients who have a documented negative AFB smear after 2 months of therapy and have no evidence of cavitation on the initial chest radiograph, a once-weekly regimen consisting of rifapentine and INH is effective. The total duration of therapy should be 6 months, but in patients whose 2-month culture remains positive and whose chest radiograph shows evidence of cavitation, the continuation phase should be extended by 3 months, to complete a 9-month treatment course (Figure 31-10).

Table 31-4 Drug Regimens for Culture-Positive Pulmonary Tuberculosis Caused by Drug-Susceptible Organisms

Some patients may be intolerant of a first-line drug or have underlying drug-resistant disease. In such cases, addition of a second-line drug may be necessary (see Table 31-3). These medications include the fluoroquinolones, PAS, ethionamide, cycloserine, clofazimine, and injectables such as kanamycin, capreomycin, and amikacin. The duration of treatment for drug-resistant TB will be determined by the drugs used, the site, and the extent of the disease. Expert consultation should be obtained for treating drug-resistant TB.

Prevention

Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection

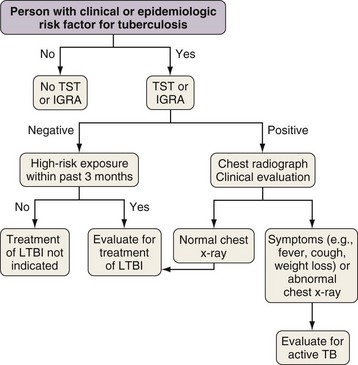

Most people who are infected with M. tuberculosis are able to arrest the development of active disease with adequate cell-mediated immunity. As noted previously, however, approximately 10% of infected people have TB develop during their lifetime. Treatment of LTBI is a pillar of TB prevention in lower incidence countries like the United States because treatment can reduce the risk of progression to TB by up to 92%. Testing for LTBI should be targeted at people with clinical and epidemiologic risks for TB (Figure 31-11). Until recently, the only method to detect LTBI was the TST. Recently, blood-based assays have been developed that provide an alternative to the TST.

Tuberculin Skin Test

Three different thresholds—5, 10, and 15 mm—have been set for defining a positive tuberculin reaction, depending on the individual or population being tested (see Table 31-1). For persons at highest risk for development of TB, a cutoff of 5 mm or more is recommended. This group includes persons known or suspected of being HIV-infected, close contacts of active TB cases, persons with an abnormal-appearing chest radiograph showing fibrosis consistent with previous TB (Figure 31-12), and other immunosuppressed patients. A cutoff of 10 mm of induration or greater is classified as positive for people at intermediate risk for TB. The remaining group consists of persons at low risk for TB who have no risk factors. In these persons, TST reactions are classified as positive if the induration is 15 mm or more across; in general, such patients should not be screened.

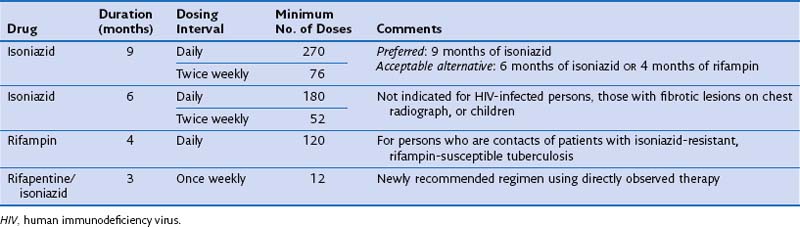

Treatment of Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Treatment is not recommended for all persons with LTBI. Instead, therapy should be provided to those persons at higher risk for TB infection and/or TB. For persons who are at increased risk of progressing to disease, treatment of latent infection is indicated, regardless of age. It is critical that patients being considered for LTBI therapy receive a clinical and radiographic evaluation to exclude the possibility of active disease. The two most commonly used drugs for the treatment of LTBI are INH and rifampin (Table 31-5).

Special Circumstances

Abnormal-Appearing Chest Radiographs

In patients with evidence of LTBI who have an abnormal-appearing chest radiograph with parenchymal fibrotic lesions (see Figure 31-12) who have not been previously treated, sputum should be collected to exclude active TB. Once active TB has been excluded, treatment options for LTBI include INH for 9 months and rifampin for 4 months.

Diseases Caused by Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

The NTM were not widely recognized as a cause of human disease until the late 1950s. In 1959, Runyon reported a classification system that organized NTM organisms into four groups on the basis of microbiologic characteristics, including the formation of pigment and the speed of growth. This system has become less useful with the development of rapid molecular methods of diagnosis, but differentiating NTM species on the basis of their rate of growth is still used today. NTM typically are divided into rapidly and slowly growing species (Table 31-6).

Table 31-6 Clinically Significant Nontuberculous Examples of Mycobacteria by Rate of Growth

| Slowly Growing (>7 days of incubation for mature growth) | Rapidly Growing (≤7 days of incubation for mature growth) |

|---|---|

* This organism often grows within 7 to 10 days.

Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Pathogenesis

Risk Factors

Skin test reactivity to mycobacterial antigens has ranged in prevalence from 11% to 33% in the United States. Predictors of skin test reactivity have included residence in the southeastern region of the country, male gender, black race, birth outside of the United States, and degree of soil exposure. Of note, however, many of the patients who develop pulmonary disease related to NTM do not have these characteristics. For example, patients with the nodular-bronchiectatic form of pulmonary disease (see “Pulmonary Disease” further on) frequently are white, postmenopausal women who were born in the United States.

Clinical Features

Pulmonary Disease

NTM pulmonary infections manifest with two prototypical radiographic patterns: fibrocavitary disease, consisting of upper lobe opacities with cavities and volume loss, and nodular bronchiectatic disease, consisting of nodules and bronchiectasis. Classically, fibrocavitary disease was recognized in older men with underlying lung disease (Figure 31-13). This radiographic pattern mimics that of TB, and NTM infection frequently is identified in the course of evaluation for TB. By contrast, nodular bronchiectatic disease typically occurs among women without known structural lung disease. Chest radiographs reveal opacities in the middle and lower lung fields. High-resolution CT scans demonstrate bronchiectasis often in the middle lobe and lingula, with evidence of small noncavitating nodules, centrilobular in location (Figure 31-14). It is important to recognize that there is a great deal of overlap between the two classic radiographic presentations and between the patterns of disease produced by the various NTM species.

Patients with M. kansasii infection usually present with upper lobe cavitary opacities, and the cavities typically are thin-walled (Figure 31-15). The chest radiograph in patients with rapidly growing mycobacterial infections usually shows multilobar, patchy, reticulonodular or mixed interstitial alveolar opacities, with an upper lobe predominance (Figure 31-16). Cavitation is reported to occur in 15% to 40%. High-resolution CT scans will show bronchiectasis and small nodules, similar to those in MAC infection.

Diagnosis

Integration of Clinical, Microbiologic, and Radiographic Data

To diagnose NTM infection, the clinician must weigh clinical, bacteriologic, and radiographic information (Box 31-1). NTM pulmonary infections should be suspected when a patient presents with a compatible clinical picture and nodular or cavitary opacities on the chest radiograph or multifocal bronchiectasis with multiple small nodules on a high-resolution CT scan. In addition to these clinical criteria, the patient should have at least two positive cultures from separate sputum specimens or a positive culture from at least one bronchial wash or lavage procedure. Additional diagnostic criteria include transbronchial or other lung biopsy specimens with mycobacterial histopathologic features and culture-positive for NTM, or a biopsy specimen showing mycobacterial histopathologic features and one or more sputum or bronchial washings that are culture-positive. In patients who do not meet the preceding definition for disease, close follow-up is indicated, because many will demonstrate progression over time.

Box 31-1

Clinical and Microbiologic Criteria for Diagnosis of Lung Disease Due to Nontuberculous Mycobacteria

Microbiologic

1. Positive culture results from at least two separate expectorated sputum samples. If results are nondiagnostic, consider repeat sputum acid-fast bacilli (AFB) smears and cultures.

2. Positive culture result from at least one bronchial wash or lavage.

3. Transbronchial or other lung biopsy with mycobacterial histopathologic features (granulomatous inflammation or AFB) and positive culture for nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) or biopsy showing mycobacterial histopathologic features (granulomatous inflammation or AFB) and one or more sputum or bronchial washings that are culture-positive for NTM.

Modified from Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al; ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America: An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases, Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175:367–416, 2007.

Treatment

Pulmonary Infections

Mycobacterium avium Complex

Before the availability of the newer macrolides, the long-term cure rate for patients treated with antituberculosis regimens was approximately 50%. Small, noncomparative studies of azithromycin- and clarithromycin-containing regimens suggest higher bacteriologic response rates, but long-term follow-up data often are lacking. The ATS currently recommends that the treatment regimen be based on the presence or absence of cavitary disease and whether or not the patient has been treated previously (Table 31-7). For patients with noncavitary nodular bronchiectasis disease, a three-times-a-week regimen may be considered. For patients with cavitary or advanced disease and in those who have been treated previously, daily therapy is recommended. An aminoglycoside should be considered in patients, at least for the first 2 to 3 months of therapy, if they have cavitary disease or if previous treatment has failed. Surgery should be considered in patients in whom the infection is due to a macrolide-resistant strain of MAC, in whom treatment has failed, or in whom cavitary disease is localized and potentially resectable.

Table 31-7 Nontuberculous Mycobacteria and Recommended Therapy

| Common Etiologic Agents | Recommended Antimicrobial Therapy | Other Etiologic Mycobacterial Species |

|---|---|---|

| M. avium complex |

Also consider amikacin 15 mg/kg (for the first 2-3 mo) 3×/wk

Can add aminoglycoside in severe disease

Also consider isoniazid and/or amikacin 15 mg/kg (for the first 2-3 mo) 3×/wk

Mycobacterium kansasii

Patients with lung disease caused by M. kansasii should be treated with INH, rifampin, and ethambutol (see Table 31-7). Substitution of clarithromycin for INH has been associated with good short-term outcomes, and in one study, no relapses were seen at follow-up evaluation after 46 months. As with other NTM infections, the treatment duration should encompass 12 months of negative sputum cultures. For patients whose isolate is resistant to the rifamycins, a three-drug regimen is recommended on the basis of data for in vitro susceptibility to clarithromycin or azithromycin, moxifloxacin, ethambutol, sulfamethoxazole, or streptomycin. Surgical resection is almost never necessary in patients infected with M. kansasii.

Rapidly Growing Mycobacteria

M. abscessus is the third most frequently encountered NTM respiratory pathogen in the United States and accounts for 80% of cases of lung disease due to rapidly growing mycobacteria. Treatment outcomes with M. abscessus generally are poor, in part because the organism is susceptible to only a few antimicrobials, including the macrolides, imipenem, cefoxitin, amikacin, tigecycline, clofazimine and occasionally linezolid. In vitro susceptibility testing is recommended for selection of a treatment regimen. As noted previously, although M. abscessus may be macrolide-susceptible in vitro, induction of the erm(41) gene may result in clinical resistance. The impact of such resistance on the efficacy of the treatment regimen is unknown, so macrolides are still recommended for treatment. Unfortunately, no antibiotic regimen has demonstrated predictable long-term sputum conversion in patients with pulmonary disease. Recent studies from South Korea and the United States reported culture conversion rates of at least 12 months in approximately 50% to 60% of patients. Current recommendations are to provide periodic drug administration of multidrug therapy, including a macrolide, and one or more parenteral agents such as amikacin, cefoxitin, or imipenem for 2 to 6 months to help control symptoms and prevent progression (see Table 31-7). For patients who are good candidates, surgical resection should be considered but only if done by an experienced surgeon and after a period of intensive antimicrobial therapy. In two studies, outcomes were better in patients who underwent surgical resection in addition to antimicrobial therapy.

American Thoracic Society. www.thoracic.org.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. www.cdc.org.

Francis J. Curry National Tuberculosis Center. www.nationaltbcenter.org.

Heartland National Tuberculosis Center. www.heartlandntbc.org.

International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. www.iuatld.org.

Northeastern Regional Training and Medical Consultation Consortium. www.umdnj.edu/globaltb/home.htm.

Southeastern National Tuberculosis Center. sntc.medicine.ufl.edu.

World Health Organization, Stop TB Partnership. www.stoptb.org.

American Thoracic Society. Diagnostic standards and classification of tuberculosis in adults and children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1376–1395.

American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:S221–S247.

American Thoracic Society; CDC; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-11):1–80.

American Thoracic Society; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Infectious Diseases Society of America. American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America: controlling tuberculosis in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172:1169–1227.

Centers for Disease. Control and Prevention (CDC): Updated guidelines for the use of nucleic acid amplification tests in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:7–10.

Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, et al An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416.

Jensen PA, Lambert LA, Iademarco MF, Ridzon R Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-17):1–141.

Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Vernon A, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection—United States, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR-5):1–25.

World Health Organization. Guidelines for the programmatic management of drug-resistant tuberculosis, 2011 update, ed 3. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

World Health Organization. Treatment of tuberculosis, guidelines, ed 4. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.