Tuberculosis

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with tuberculosis.

• Describe the causes of tuberculosis.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with tuberculosis.

• Describe the general management of tuberculosis.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAP presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

Primary Tuberculosis

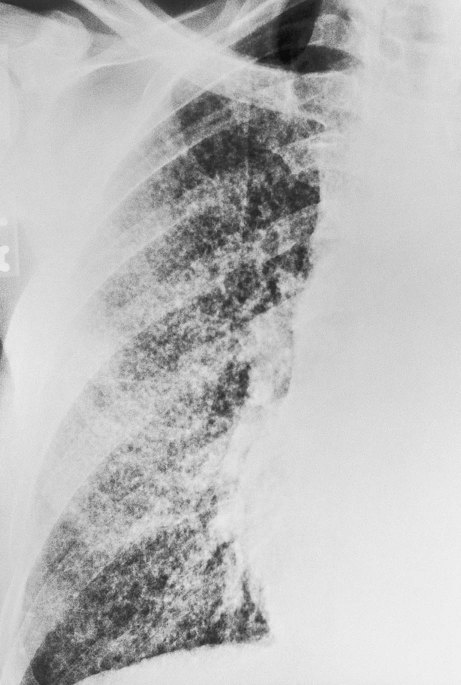

Primary TB (also called the primary infection stage) follows the patient’s first exposure to the TB pathogen, Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Primary TB begins when the inhaled bacilli implant in the alveoli. As the bacilli multiply over a 3- to 4-week period, the initial response of the lungs is an inflammatory reaction that is similar to any acute pneumonia (see Figure 15-1). In other words, a large influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages moves into the infected area to engulf—but not fully kill—the bacilli. This action also causes the pulmonary capillaries to dilate, the interstitium to fill with fluid, and the alveolar epithelium to swell from the edema fluid. Eventually the alveoli become consolidated (i.e., filled with fluid, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and macrophages). Clinically, this phase of TB coincides with a positive tuberculin reaction—a positive purified protein derivative (PPD) skin test result (see discussion of diagnosis later in this chapter).

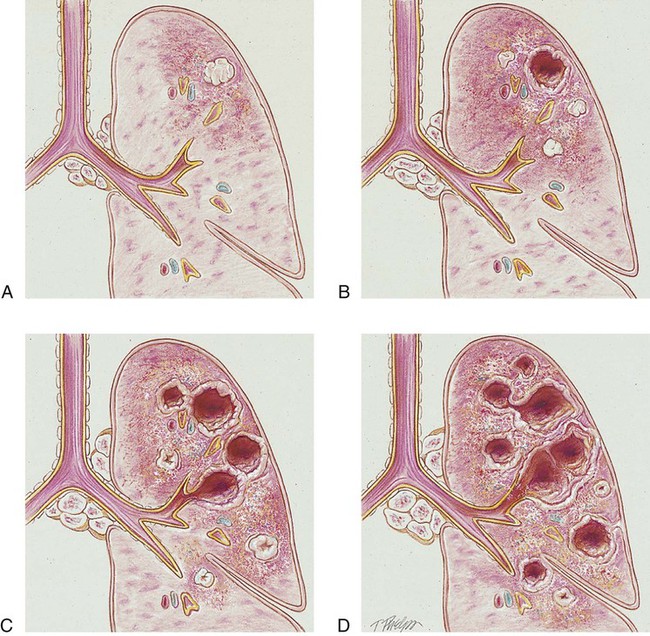

Unlike pneumonia, however, the lung tissue that surrounds the infected area slowly produces a protective cell wall called a tubercle, or granuloma. In essence, the tubercles work to encapsulate—that is, put in a nutshell-like structure—the TB bacilli (see Figure 17-1, A). Although the initial lung lesions may be difficult to identify on a chest radiograph, the lesions may be seen as small, sharply defined opacities. When detected on a chest radiograph, these initial lung lesions are called Ghon nodules. As the disease progresses, the combination of tubercles and the involvement of the lymph nodes in the hilar region is known as the Ghon complex.

Structurally, a tubercle consists of a central core containing TB bacilli. The central core also has enlarged macrophages with an outer wall composed of fibroblasts, lymphocytes, and neutrophils. A tubercle takes about 2 to 10 weeks to form. The function of the tubercle is to contain the TB bacilli, thus preventing the further spread of infectious TB organisms. Unfortunately, the central core of the tubercle has the potential to break down from time to time, especially in a patient with a depressed immune system. When this happens, the center of the tubercle fills with necrotic tissue that resembles dry cottage cheese. During this stage the tubercle is called a caseous lesion or caseous granuloma (see Figure 17-1, B). The patient is potentially contagious at this stage. In most cases, however, the TB bacilli are effectively contained within the tubercles.

Postprimary Tuberculosis

• People in institutional housing (e.g., nursing homes, prisons, homeless shelters)

• People living in overcrowded conditions

• Immunosuppressed patients (e.g., organ transplant patients, cancer patients)

• Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–infected patients (TB is a leading cause of death in HIV patients)

If the TB infection is uncontrolled, cavitation of the caseous granuloma tubercle develops. The patient progressively experiences more severe symptoms, including violent cough episodes, greenish or bloody sputum, low-grade fever, anorexia, weight loss, extreme fatigue, night sweats, and chest pain. It is this gradual wasting of the body that provided the basis for the earlier name for TB—consumption. The patient is highly contagious at this stage. In severe cases a deep tubercle cavity may rupture and allow air and infected material to flow into the pleural space or the tracheobronchial tree. Pleural complications are common in TB (see Figure 17-1, C).

Diagnosis

Mantoux Tuberculin Skin Test

The most widely used tuberculin test is the Mantoux test, which consists of an intradermal injection of a small amount of a PPD of the tuberculin bacillus (Figure 17-2). The skin is then observed for induration (a wheal) after 48 hours and 72 hours, with results interpreted as follows:

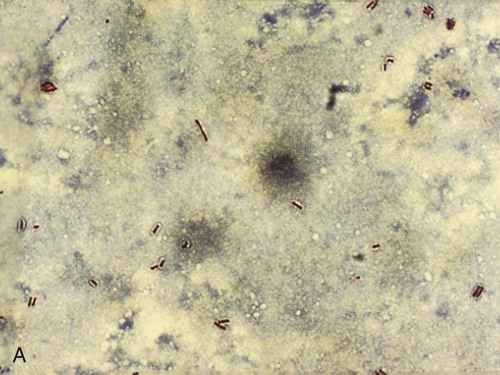

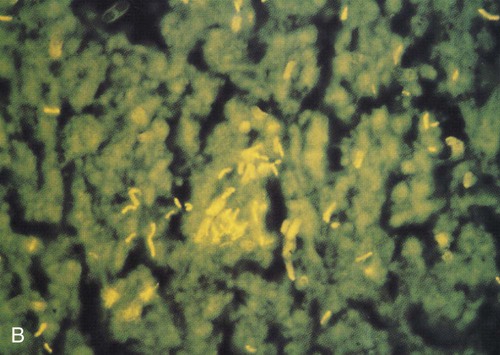

Acid-Fast Staining

Because the M. tuberculosis organism has an unusual, waxy coating on the cell surface, which makes the cells impervious to staining, an acid-fast bacteria (AFB) test (also called a sputum smear) is performed instead. Several variations of the acid-fast stain are currently in use. The frequently used Ziehl-Neelsen stain reveals bright red acid-fast bacilli against a blue background (Figure 17-3, A). Another popular technique involves a fluorescent acid-fast stain that reveals luminescent yellow-green bacilli against a dark brown background. The fluorescent acid-fast stain is becoming the acid-fast test of choice because it is easier to read and provides a striking contrast (Figure 17-3, B).

Sputum Culture

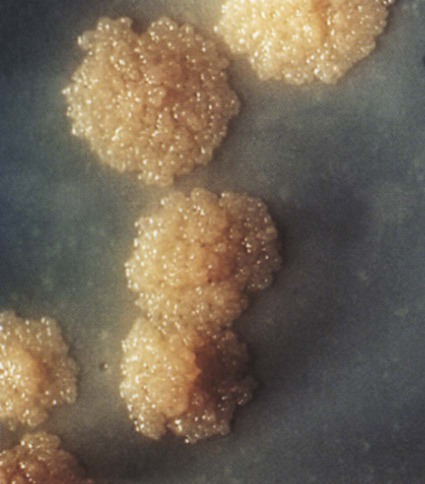

Because a variety of nontuberculous strains of Mycobacterium can show up on an AFB smear, a sputum culture is often necessary to differentiate M. tuberculosis from other acid-fast organisms. For example, common nontuberculous acid-fast mycobacteria associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium kansasii. Sputum cultures can also identify drug-resistant bacilli and their sensitivity to antibiotic therapy. M. tuberculosis grows very slowly. It takes up to 6 weeks for colonies to appear in culture. When the TB bacterium was first studied, it was given the misleading prefix Myco, which gave the impression that the TB pathogen was fungal in nature. This was because the bacterium growing in agars appeared as colonies, similar to fugal colonies (Figure 17-4). They are unrelated; TB is caused by a bacterium and not a fungus.

General Management of Tuberculosis

Pharmacologic Agents Used to Treat Tuberculosis

• 6-month treatment protocol: For the first 2 months (called the induction phase) the patient takes a daily dose of isoniazid (INH), rifampin, pyrazinamide, and either ethambutol or streptomycin. For the next 4 months the patient takes isoniazid and rifampin daily or twice weekly.

• 9-month treatment protocol: For the first 1 to 2 months the patient takes a daily dose of isoniazid and rifampin, followed by twice-weekly isoniazid and rifampin until the full 9-month period has been completed.

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

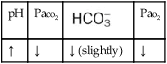

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. Because of the hypoxemia associated with TB, supplemental oxygen may be required. The hypoxemia that develops in patients with lung abscess is usually caused by pulmonary capillary shunting. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is often refractory to oxygen therapy. In addition, when the patient demonstrates chronic ventilatory failure during the advanced stages of TB, caution must be taken not to overoxygenate the patient (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the excessive mucous production and accumulation sometimes associated with severe TB, a number of bronchial hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

Mechanical Ventilation Protocol

Because acute ventilatory failure is occasionally associated with TB, mechanical ventilation may be required to maintain an adequate ventilatory status. Continuous mechanical ventilation is justified when the acute ventilatory failure is thought to be reversible—for example, when pneumonia complicates the condition (see Mechanical Ventilation Protocols, Protocol 9-5, Protocol 9-6, and Protocol 9-7).

CASE STUDY

Tuberculosis

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S Productive cough, slight hemoptysis; moderate dyspnea. History of left-sided chest pain for 10 days.

O Febrile to 102.4° F. RR 32, HR 116, BP 132/90. Room air Spo2 90%. Productive cough: large amounts yellow, blood-streaked sputum. Crackles and rhonchi in right upper and middle lobes. CXR: Apical calcification; RUL cavity; RML infiltrate/consolidation.

• Probable tuberculosis (patient possibly infectious)

P Flag chart: Continue respiratory isolation pending AFB smear results. Obtain sputum for routine, anaerobic, and acid-fast cultures and cytology—induce if necessary. Obtain baseline ABG on room air. Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol: C&DB q2h. Based on ABG results, titrate oxygen therapy per Oxygen Therapy Protocol. Discuss need for bedside spirogram with physician.

Discussion

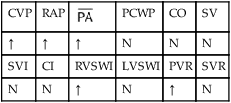

Two primary clinical scenarios were activated in this case. First, the Alveolar Consolidation (see Figure 9-9) identified on the chest x-ray film reflected the patient’s challenged immune response. This was further manifested by the objective data noted at the patient’s bedside—fever, dull percussion notes, and increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. In addition, the alveolar consolidation undoubtedly contributed to the patient’s pulmonary shunting and mild hypoxemia (see Figure 9-9).

Secondly, clinical manifestations associated with Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-12) also were present in this patient: daily cough, yellow sputum production, crackles, and rhonchi. His oxygen desaturation was mild (Spo2 = 90%), and a room air ABG and subsequent oxygen titration (presumably with low-flow oxygen by nasal cannula) were appropriate.

As expected, the patient produced sputum containing acid-fast organisms. The attending physician prescribed isoniazid, rifampin, and streptomycin for 2 months, followed by an outpatient course of isoniazid and rifampin for 4 months. The patient also was instructed regarding several different Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy (see Protocol 9-2) to perform at home. The patient did well through 1 year of follow-up.

)

)

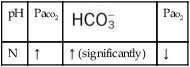

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  , mixed venous oxygen saturation;

, mixed venous oxygen saturation;  , oxygen consumption.

, oxygen consumption.

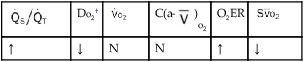

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.

, mean pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance; RAP, right atrial pressure; RVSWI, right ventricular stroke work index; SV, stroke volume; SVI, stroke volume index; SVR, systemic vascular resistance.