Truncal and Highly Selective Vagotomy

Clinical Indications

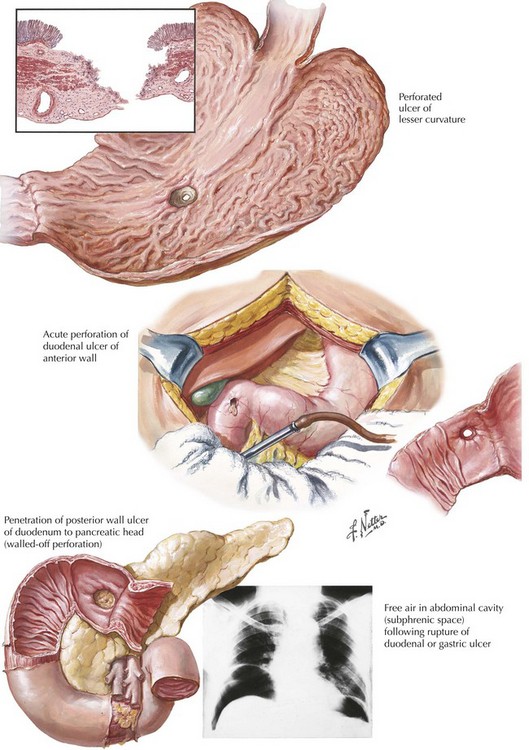

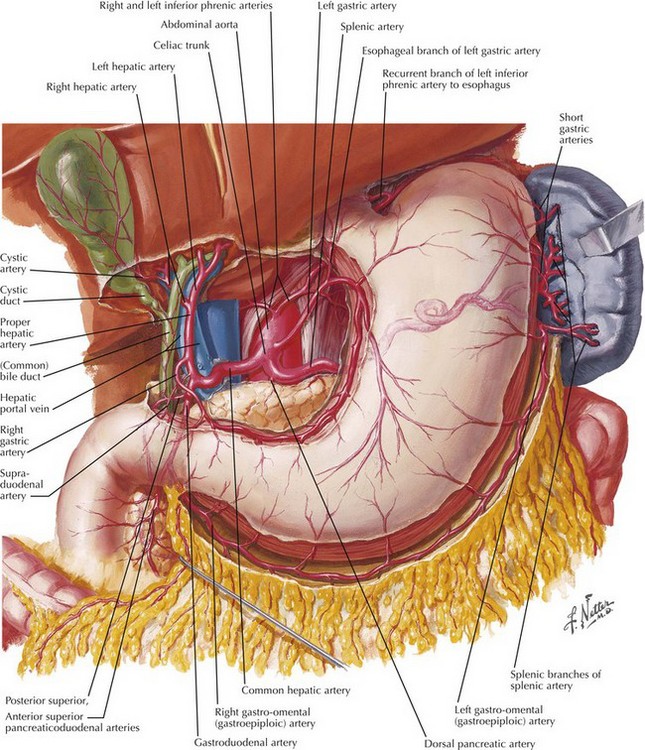

Acute ulcer disease presents as acute gastrointestinal hemorrhage or perforation (Fig. 7-1). Knowledge of the anatomy of the stomach and its surrounding arterial supply can help predict the complication of ulceration (Fig. 7-2). Erosion of the ulcer posteriorly into the gastroduodenal artery can lead to life-threatening hemorrhage, presenting as tachycardia, hypotension, and hematemesis. Anterior erosion can lead to perforation of the duodenal wall with an acute abdomen, including tachycardia, abdominal tenderness with guarding and rigidity, and pneumoperitoneum on upright chest radiograph. In a more chronic scenario, recurrent episodes may lead to gastric outlet obstruction from repeated scarring.

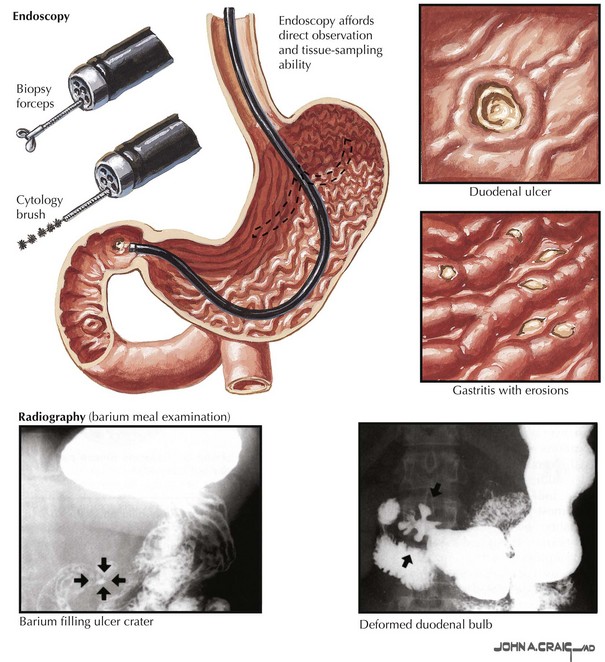

Less severe presentations of peptic ulcer disease often include complaints of burning epigastric abdominal pain. Definitive diagnosis and elimination of other conditions can be made by upper gastrointestinal endoscopy or upper gastrointestinal series (Fig. 7-3). Any gastric ulcerations seen on endoscopy should be biopsied at multiple sites around the border to determine if the lesion harbors a malignancy. Patients should be evaluated for the presence of H. pylori and treated if positive. They should also undergo medical treatment with acid suppression medication before surgery is considered. Patients with persistent severe disease, especially after maximal medical therapy and treatment for H. pylori, should be considered for a definitive acid-reducing procedure.

Innervation of Stomach

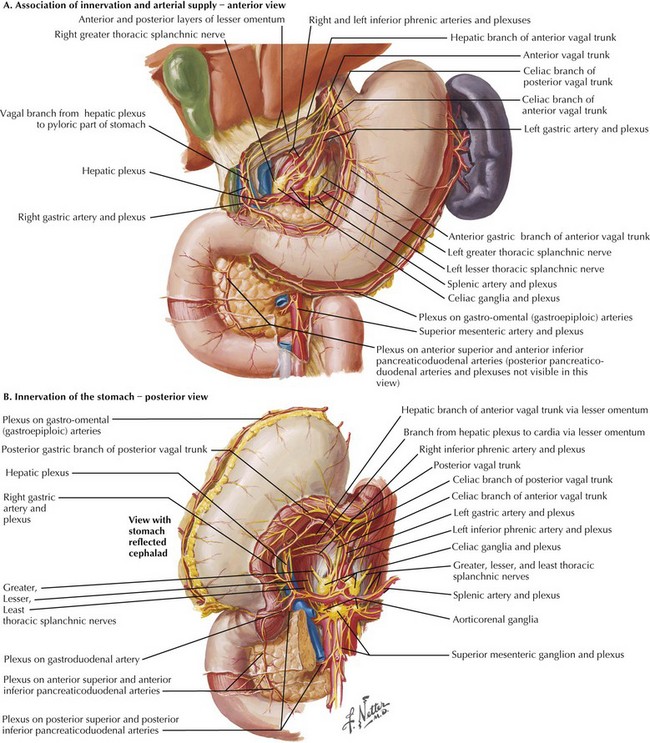

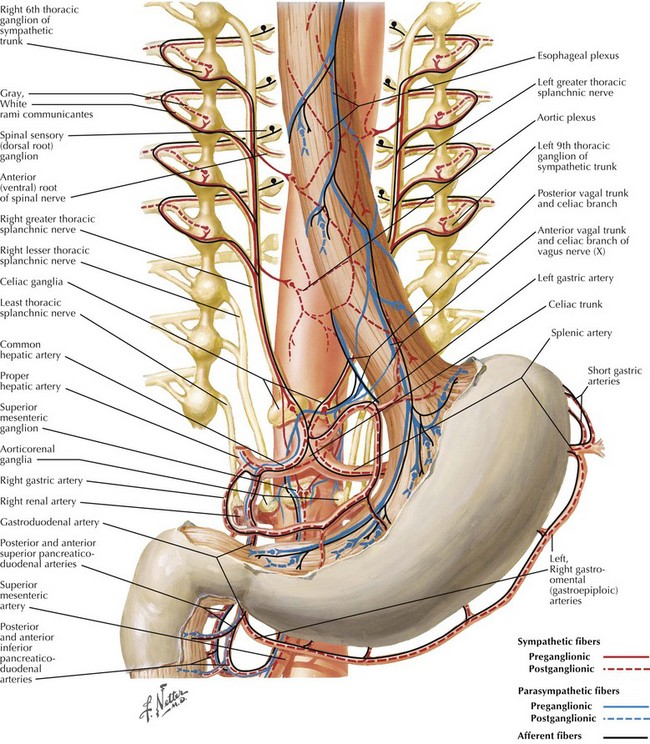

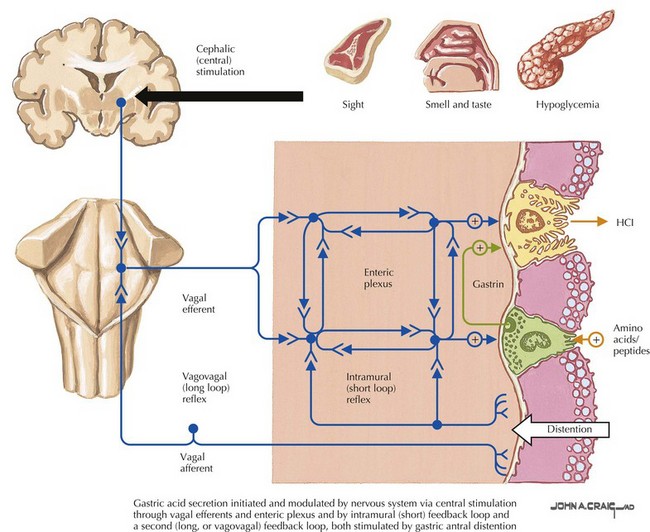

Sympathetic innervation parallels the arterial supply of the stomach (Fig. 7-4, A). Parasympathetic innervation is controlled by the vagus nerve, with one trunk on the right and one on the left that enter from the thoracic cavity with the esophagus (Fig. 7-5). As the vagus nerve enters the abdomen, the two nerves rotate so that the left trunk becomes anterior and the right trunk posterior to the esophagus. Both trunks innervate the stomach along the lesser curvature. Vagal stimulus to the stomach induces the parietal cells to secrete hydrochloric acid and control the motor activity of the stomach (Fig. 7-6).

The left/anterior vagus nerve continues to give off a branch that innervates the gallbladder, biliary tract, and liver. The right/posterior vagus nerve continues to innervate the pancreas, small intestine, and proximal colon. The right branch gives off a small branch behind the esophagus called the “criminal nerve of Grassi” that, if not divided, can lead to recurrent disease (Fig. 7-4, B). The vagus nerve also supplies motor function to the circular muscle fibers of the antrum and pylorus, which is why a drainage procedure is important after truncal vagotomy (see Chapter 10).

Truncal Vagotomy

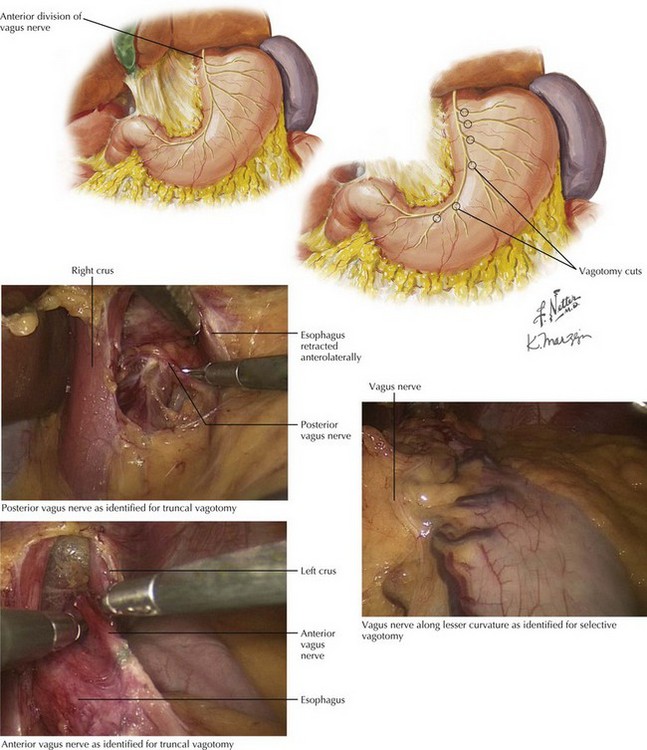

Truncal vagotomy involves complete transaction of the vagus nerve at or above the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus. Figures 7-4 and 7-5 illustrate the anatomic site for division. This approach denervates not only the parietal cells but also the abdominal viscera, including the antral pump and pyloric sphincter mechanism. Because the truncal vagotomy disrupts gastric motility, a gastric drainage procedure is required for gastric emptying. The most common procedure is a pyloroplasty, although antrectomy with reconstruction is another viable option, as is gastrojejunostomy (see Chapters 5 and 8).

The surgical approach for truncal vagotomy involves adequate mobilization of the left lobe of the liver to allow for exposure of the diaphragmatic hiatus. The phrenoesophageal ligament is opened with electrocautery, and gentle downward traction on the stomach aids with visualization. Exposure is accomplished through traction right and posteriorly and for the left (anterior) nerve and traction left and anteriorly for the right (posterior) nerve (Fig. 7-7). Once identified, the main trunk is then clipped both proximally and distally and divided, removing a segment at least 2 cm in length for pathologic confirmation.

Highly Selective Vagotomy

Highly selective vagotomy, also referred to as proximal gastric vagotomy or parietal cell vagotomy, divides only the branches of the vagus nerve that innervate the parietal cell mass. Figure 7-4 illustrates the anatomic site for division. The preservation of the “crow’s foot” (terminal and most distal divisions of vagus nerve) allows the antral pump and pyloric sphincter mechanisms to remain intact, eliminating the need for a gastric emptying procedure.

The surgical approach begins by examining the lesser curve of the stomach to identify the left gastric vessels and the gastric branch of the anterior vagus nerve (Fig. 7-7). Division of the distal branches of the vagus nerve occurs on the stomach side of the left gastric artery, leaving the crow’s foot, typically located near the incisura angularis (angular or gastric notch), intact for gastric emptying. This dissection starts approximately 7 cm proximal to the pylorus and should be continued to the gastroesophageal junction, taking care to stay close to the stomach and leave the main trunk of the vagus nerve intact. The distal esophagus should be denervated for 6 cm in length to ensure adequate parietal cell signal disruption.

Bertleff, MJ, Lange, JF. Laparoscopic correction of perforated peptic ulcer: first choice? A review of literature. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(6):1231–1239.

Donahue, PE. Parietal cell vagotomy versus vagotomy-antrectomy: ulcer surgery in the modern era. World J Surg. 2000;24(3):264–269.

Steger, AC, Galland, RB, Spencer, J. Remaining indications for vagotomy with drainage or antrectomy in duodenal ulcer. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1987;69(1):24–26.

Zittel, TT, Jehle, EC, Becker, HD. Surgical management of peptic ulcer disease today: indication, technique and outcome. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2000;385(2):84–96.