CHAPTER 63 True pelvis, pelvic floor and perineum

TRUE PELVIS AND PELVIC FLOOR

The true pelvis is a bowl-shaped structure formed from the sacrum, pubis, ilium, ischium, the ligaments which interconnect these bones and the muscles which line their inner surfaces. The true pelvis is considered to start at the level of the plane passing through the promontory of the sacrum, the arcuate line on the ilium, the iliopectineal line and the posterior surface of the pubic crest. This plane, or ‘inlet’ lies at an angle of between 35 and 50° up from the horizontal and above this the bony structures are sometimes referred to as the false pelvis. They form part of the walls of the lower abdomen. The floor or ‘outlet’ of the true pelvis is formed by the muscles of levator ani. Although the floor is gutter shaped, it generally lies in a plane between 5 and 15° up from the horizontal. This difference between the planes of the inlet and outlet is the reason why the true pelvis is said to have an axis (lying perpendicular to the plane of both inlet and outlet) which progressively changes through the pelvis from above downwards. The details of the topography of the bony and ligamentous pelvis are considered fully on page 1358.

MUSCLES AND FASCIAE OF THE PELVIS

Pelvic muscles

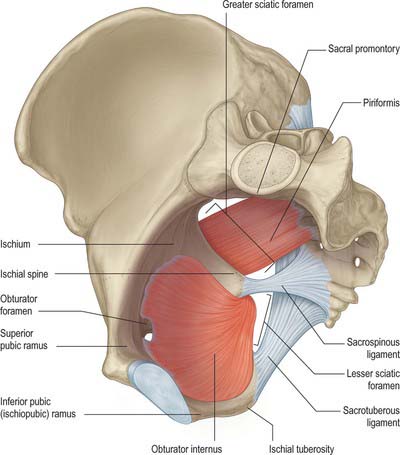

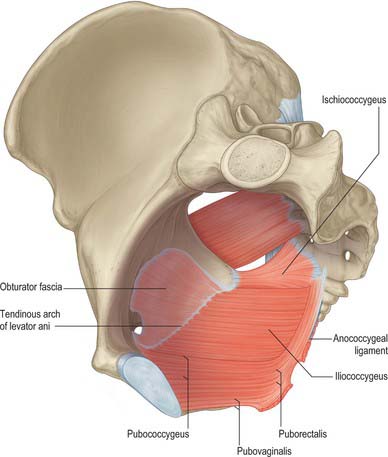

The muscles arising within the pelvis form two groups. Piriformis and obturator internus, although forming part of the walls of the pelvis, are considered as primarily muscles of the lower limb (Fig. 63.1). Levator ani and coccygeus form the pelvic diaphragm and delineate the lower limit of the true pelvis (Fig. 63.2). The fasciae investing the muscles are continuous with visceral pelvic fascia above, perineal fascia below and obturator fascia laterally.

Piriformis

The complete description of piriformis is in Chapter 80.

Piriformis (see p. 1371) forms part of the posterolateral wall of the true pelvis and is attached to the anterior surface of the sacrum, the gluteal surface of the ilium near the posterior inferior iliac spine, the capsule of the adjacent sacroiliac joint and sometimes to the upper part of the pelvic surface of the sacrotuberous ligament. It passes out of the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen. Within the pelvis, the anterior surface of piriformis is related to the rectum (especially on the left), the sacral plexus of nerves and branches of the internal iliac vessels. The posterior surface lies against the sacrum.

Obturator internus

Obturator internus (see p. 1371) and the fascia over its upper inner (pelvic) surface form part of the anterolateral wall of the true pelvis. It is attached to the structures surrounding the obturator foramen, the inferior ramus of the pubis, the ischial ramus, the pelvic surface of the hip bone below and behind the pelvic brim, and the upper part of the greater sciatic foramen. It also attaches to the medial part of the pelvic surface of the obturator membrane. The muscle is covered by a thick fascial layer and the fibres themselves cannot be seen directly from within the pelvis. This fascia gives attachment to some of the fibres of levator ani and thus only the upper portion of the muscle lies lateral to the contents of the true pelvis, whilst the lower portion forms part of the boundaries of the ischio-anal fossa. In the male, the upper portion lies lateral to the bladder, the obturator and vesical vessels, and the obturator nerve. In the female, the attachments of the broad ligament of the uterus, the ovarian end of the uterine tubes, and the uterine vessels, also lie medial to obturator internus and its fascia.

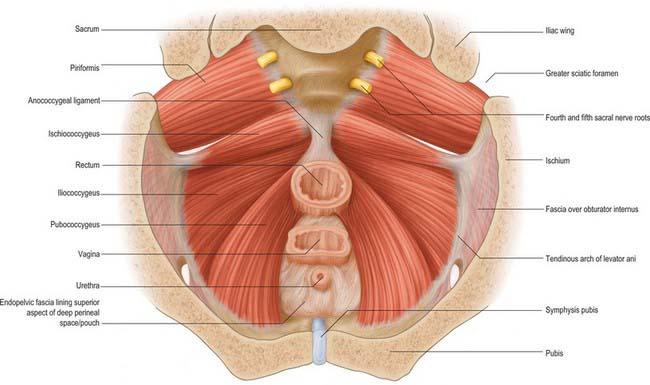

Levator ani (ischiococcygeus, iliococcygeus, pubococcygeus)

Levator ani is a broad muscular sheet of variable thickness which is attached to the internal surface of the true pelvis and forms a large portion of the pelvic floor (Fig. 63.3). The muscle is subdivided into named portions according to their attachments and the pelvic viscera to which they are related. These parts are often referred to as separate muscles, but the boundaries between each part cannot be easily distinguished and they perform many similar physiological functions. The separate parts are referred to as ischiococcygeus, iliococcygeus and pubococcygeus. Pubococcygeus is often subdivided into separate parts according to the pelvic viscera to which they relate (puboperinealis, puboprostaticus or pubovaginalis, puboanalis, puborectalis). Levator ani arises from each side of the walls of the pelvis along the condensation of the obturator fascia (the tendinous arch of levator ani; see below). Fibres from ischiococcygeus attach to the sacrum and coccyx but the remaining parts of the muscle converge in the midline. The fibres of iliococcygeus join by a partly fibrous intersection and form a raphe posterior to the anorectal junction. Closer to the anorectal junction and elsewhere in the pelvic floor, the fibres are more nearly continuous with those of the opposite side and the muscle forms a sling (puborectalis and pubovaginalis or pubourethralis).

The attachments for the ischiococcygeus, iliococcygeus and pubococcygeus parts are as follows.

The iliococcygeal part is attached to the inner surface of the ischial spine below and anterior to the attachment of ischiococcygeus and to the tendinous arch as far forward as the obturator canal (Fig. 63.2). The most posterior fibres are attached to the tip of the sacrum and coccyx but most join with fibres from the opposite side to form a raphe. This raphe is effectively continuous with the fibroelastic anococcygeal ligament, which is closely applied to its inferior surface and some muscle fibres may attach into the ligament. The raphe provides a strong attachment for the pelvic floor posteriorly and must be divided to allow wide excisions of the anorectal canal during abdominoperineal excisions for malignancy. An accessory slip may arise from the most posterior part and is sometimes referred to as iliosacralis.

The pubococcygeal part is attached to the back of the body of the pubis and passes back almost horizontally. The most medial fibres run directly lateral to the urethra and its sphincter as it passes through the pelvic floor; here the muscle is correctly called the puboperinealis, although due to its close relationship to the upper half of the urethra in both sexes it is often referred to as pubourethralis. The muscle fibres from both sides form part of the urethral sphincter complex together with the intrinsic striated and smooth musculature of the urethra; fibres decussate across the midline directly behind the urethra. In males some of these fibres lie lateral and inferior to the prostate and are referred to as puboprostaticus (levator prostatae). In females, some fibres form the pubourethralis, others run further back to form a sling around the posterior wall of the vagina where they are referred to as pubovaginalis. In both sexes, fibres from this part of pubococcygeus attach to the perineal body; a few elements also attach to the anorectal junction. Some of these fibres, sometimes called puboanalis, decussate and blend with the longitudinal rectal muscle and fascial elements to contribute to the conjoint longitudinal coat of the anal canal. Behind the rectum, some fibres of pubococcygeus form a tendinous intersection as part of the levator raphe, and a thick muscular sling, puborectalis, wraps around the anorectal junction. Some fibres blend with those of the external anal sphincter. Pubourethralis, pubovaginalis/puboprostaticus and puboanalis are sometimes collectively referred to as ‘pubovisceralis’.

Levator ani is supplied by branches of the inferior gluteal, inferior vesical and pudendal arteries.

Fibres which originate mainly in the second, third and fourth sacral spinal segments reach levator ani from below and above by a variety of routes (Wendell-Smith & Wilson 1991). Most commonly, pubococcygeus is supplied by second and third sacral spinal segments via the pudendal nerve, and ischiococcygeus and iliococcygeus by direct branches of the sacral plexus from the third and fourth sacral spinal segments.

Pelvic fasciae

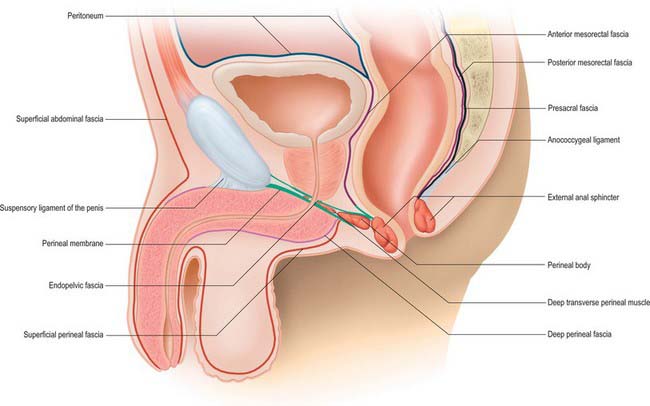

The pelvic fasciae may be conveniently divided into the parietal pelvic fascia, which mainly forms the coverings of the pelvic muscles, and the visceral pelvic fascia, which forms the coverings of the pelvic viscera and their vessels and nerves (Fig. 63.4).

Parietal pelvic fascia

Obturator fascia

The parietal pelvic fascia on the pelvic (medial) surface of obturator internus is well differentiated. Although in humans it is derived from the degenerate upper portion of the attachment of levator ani, it is usually referred to as the obturator fascia. Above, it is connected to the posterior part of the arcuate line of the ilium, and is continuous with iliac fascia. Anterior to this, as it follows the line of origin of obturator internus, it is gradually separated from the attachment of the iliac fascia and a portion of the periosteum of the ilium and pubis spans between them. It arches below the obturator vessels and nerve, investing the obturator canal, and is attached anteriorly to the back of the pubis. Behind the obturator canal, the fascia is markedly aponeurotic and gives a firm attachment to levator ani, usually called the tendinous arch of levator ani (arcus tendineus musculi levatoris ani) (see Figs 63.3, 63.13, 63.14). Below the attachment of levator ani, the fascia is thin and is effectively composed only of the epimysium of the muscle and overlying connective tissue; posteriorly it forms part of the lateral wall of the ischio-anal fossa in the perineum, and anteriorly it merges with the fasciae of the muscles of the deep perineal space (see Fig. 63.14), which is continuous with the ischio-anal fossa. The obturator fascia is continuous with the pelvic periosteum and thus the fascia over piriformis.

Fascia over piriformis

The fascia over the inner aspect of piriformis is very thin, and fuses with the periosteum on the front of the sacrum at the margins of the anterior sacral foramina. It ensheathes the sacral anterior primary rami which emerge from these foramina: the nerves are often described as lying behind the fascia. The internal iliac vessels lie in front of the fascia over piriformis; their branches draw out sheaths of the fascia and extraperitoneal tissue into the gluteal region, above and below piriformis.

Fascia over levator ani (pelvic diaphragm)

Arcus tendineus fascia pelvis/white line of the parietal pelvic fascia

Low on the superomedial aspect of the upper fascia over levator ani, a thick white band of condensed connective tissue extends from the lower part of the symphysis pubis to the inferior margin of the spine of the ischium (see Figs 63.4, 63.13, 63.14). Although often referred to as the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia (arcus tendineus fasciae pelvis), it is really the remnant of the degenerate tendon of iliococcygeus in humans and is best referred to as the white line of the parietal pelvic fascia (Smith 1908). It provides attachment for the condensations of visceral pelvic fascia which provide support to the urethra, bladder and vagina in females (see below).

Visceral pelvic fascia

In the female, pubourethral ligaments form from periurethral connective tissue and attach to the white line of the parietal pelvic fascia close to its pubic end. A little more laterally, similar tissue exists which may be termed the urethropelvic ligaments, and which insert into the white line over levator ani. These condensations are effectively continuous with connective tissue which runs from the paravaginal tissue to the white line, and is sometimes referred to as the vaginolevator support or attachment. Since the normal angle of the urethra during standing is nearly 45° to the vertical, these two structures combined can be viewed as providing a ‘hammock-like’ support to the midurethra (DeLancey 1994); some fibres may even decussate across the midline between the urethra and the anterior vaginal wall. The upper portion of the pubourethral ligament blends with the pubovesical and vesicopelvic ligaments (connective tissue around the neck of the urinary bladder), and may contain cholinergically innervated smooth muscle fibres, sometimes referred to as pubovesicalis. In males, pubourethral structures are augmented by the puboprostatic ligament/puboprostaticus. In both sexes, these muscles may have a role in opening the upper urethra and bladder neck during micturition.

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE OF THE PELVIS

Arteries of the pelvis

Internal iliac arteries

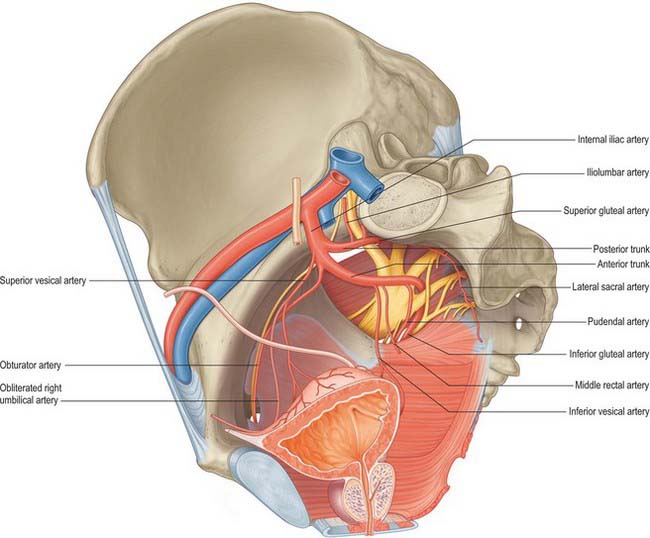

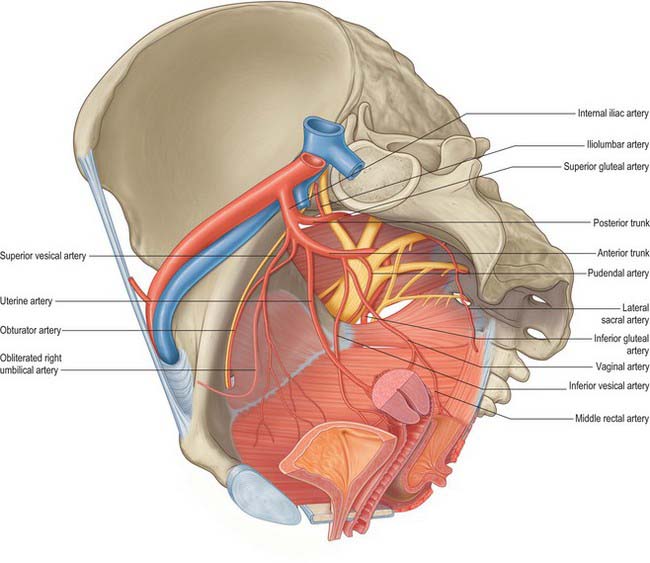

Each internal iliac artery, approximately 4 cm long, begins at the common iliac bifurcation, level with the lumbosacral intervertebral disc and anterior to the sacroiliac joint. It descends posteriorly to the superior margin of the greater sciatic foramen where it divides into an anterior trunk, which continues in the same line towards the ischial spine, and a posterior trunk, which passes back to the greater sciatic foramen. Anterior to the artery are the ureter and, in females, the ovary and fimbriated end of the uterine tube. The internal iliac vein, lumbosacral trunk and sacroiliac joint are posterior. Lateral is the external iliac vein, between the artery and psoas major, and the obturator nerve lying inferior to the vein. The parietal peritoneum is medial, separating it from the terminal ileum on the right and the sigmoid colon on the left. Tributaries of the internal iliac vein are also medial (Fig. 63.5).

Anterior trunk branches

In females the vaginal artery may replace the inferior vesical artery. It may arise from the uterine artery close to its origin (Fig. 63.6).

Internal pudendal artery (in the pelvis)

The internal pudendal artery arises just below the origin of the obturator artery. It descends laterally to the inferior rim of the greater sciatic foramen, where it leaves the pelvis between piriformis and ischiococcygeus to enter the gluteal region. It then curves around the dorsum of the ischial spine to enter the perineum by the lesser sciatic foramen. This course effectively allows the nerve to wrap around the posterior limit of levator ani at its attachment to the ischial spine and so gain access to the perineum. In the pelvis the internal pudendal artery crosses anterior to piriformis, the sacral plexus and the inferior gluteal artery. Behind the ischial spine it is covered by gluteus maximus, with the pudendal nerve medial and the nerve to obturator internus lateral to it. The internal pudendal artery gives off several muscular branches in the pelvis and gluteal region which supply adjacent muscles and nerves.

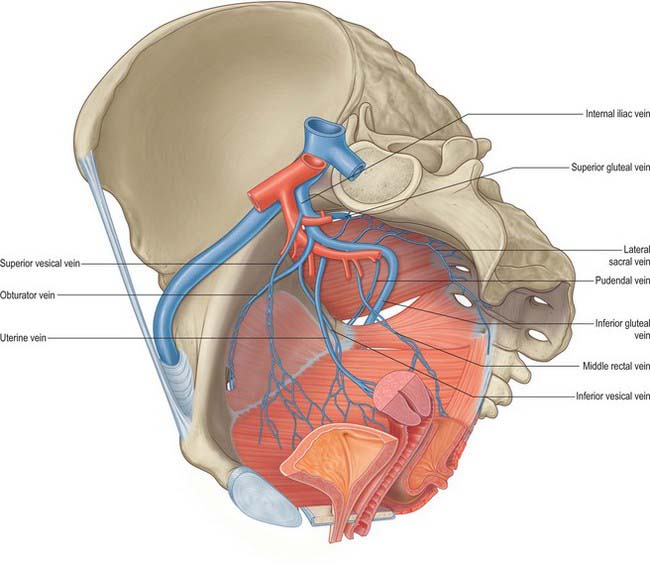

Veins of the pelvis

Internal iliac vein

The internal iliac vein is formed by the convergence of several veins above the greater sciatic foramen. It does not have the predictable trunks and branches of the internal iliac artery but its tributaries drain the same territories. It ascends posteromedial to the internal iliac artery to join the external iliac vein, forming the common iliac vein at the pelvic brim, anterior to the lower part of the sacroiliac joint. It is covered anteromedially by parietal peritoneum. Its tributaries are the gluteal, internal pudendal and obturator veins, which originate outside the pelvis; the lateral sacral veins, which run from the anterior surface of the sacrum; and the middle rectal, vesical, uterine and vaginal veins, which originate in the venous plexuses of the pelvic viscera (Fig. 63.7).

The inferior gluteal veins are venae comitantes of the inferior gluteal artery. They begin proximally and posterior in the thigh, where they anastomose with the medial circumflex femoral and first perforating veins, and enter the pelvis low in the greater sciatic foramen, joining to form a vessel opening into the distal (lower) part of the internal iliac vein. The inferior gluteal and superficial gluteal veins connect by perforating veins (Doyle 1970) which are analogous to the sural perforating veins. The gluteal veins probably have a venous ‘pumping’ role, and provide collaterals between the femoral and internal iliac veins.

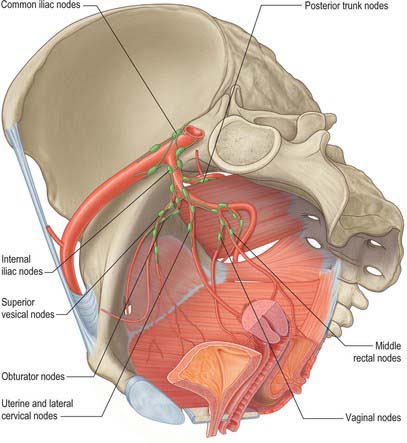

Lymphatic drainage of the pelvis

Internal iliac nodes

The internal iliac nodes surround the branches of the internal iliac vessels. They receive afferents from most of the pelvic viscera (with the exception of the gonads and the majority of the rectum), the deeper parts of the perineum and the gluteal and posterior femoral muscles, and drain to the common iliac nodes. The individual groups are considered in the description of the viscera. There are frequent connections between the right and left groups particularly when they lie close to the anterior and posterior midlines (Fig. 63.8).

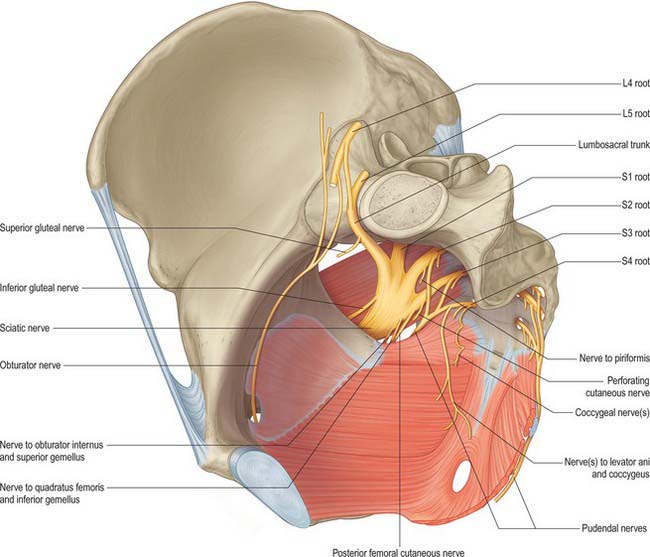

INNERVATION OF THE PELVIS

The ventral rami of the sacral and coccygeal spinal nerves form the sacral and coccygeal plexuses (Fig. 63.9). The upper four sacral ventral rami enter the pelvis by the anterior sacral foramina, the fifth enters between the sacrum and coccyx, and the ventral ramus of the coccygeal nerve curves forwards below the rudimentary transverse process of the first coccygeal segment. The first and second sacral ventral rami are large, the third to fifth diminish progressively, and the coccygeal is the smallest. Each receives a grey ramus communicans from a corresponding sympathetic ganglion. Visceral efferent rami leave the second to fourth sacral rami as the pelvic splanchnic nerves, containing parasympathetic fibres to minute ganglia in the walls of the pelvic viscera.

Lumbosacral trunk and sacral plexus

The lumbar part of the lumbosacral trunk contains part of the fourth and all the fifth lumbar ventral rami; it appears at the medial margin of psoas major, and descends over the pelvic brim anterior to the sacroiliac joint to join the first sacral ramus. The greater part of the second and third sacral rami converge on the inferomedial aspect of the lumbosacral trunk in the greater sciatic foramen to form the sciatic nerve. The ventral and dorsal divisions of the nerves do not separate physically from each other, but their fibres remain separate within the rami; the ventral and dorsal divisions of each contributing root join within the sciatic nerve. The fibres of the dorsal divisions will go on to form the common fibular nerve and the fibres of the ventral division form the tibial nerve. The sciatic nerve occasionally divides into common fibular and tibial nerves inside the pelvis. In these cases the common fibular nerve usually runs through piriformis.

The sacral plexus lies against the posterior pelvic wall anterior to piriformis, posterior to the internal iliac vessels and ureter, and behind the sigmoid colon on the left. The superior gluteal vessels run either between the lumbosacral trunk and first sacral ventral ramus or between the first and second sacral rami, while the inferior gluteal vessels lie between either the first and second or second and third sacral rami (Fig. 63.9).

Branches of the sacral plexus

| Ventral divisions | Dorsal divisions | |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve to quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior | L4,5, S1 | |

| Nerve to obturator internus and gemellus superior | L5, S1,2 | |

| Nerve to piriformis | S2 (S1) | |

| Superior gluteal nerve | L4,5, S1 | |

| Inferior gluteal nerve | L5, S1,2 | |

| Posterior femoral cutaneous nerve | S2,3 | S1,2 |

| Tibial (sciatic) nerve | L4,5, S1,2,3 | |

| Common fibular (sciatic) nerve | L4,5, S1,2 | |

| Perforating cutaneous nerve | S2,3 | |

| Pudendal nerve | S2,3,4 | |

| Nerves to levator ani and external anal sphincter | S4 | |

| Pelvic splanchnic nerves | S2,3 (S4) |

The course and distribution of most of the branches of the sacral plexus are covered fully on page 1384.

Coccygeal plexus

The coccygeal plexus is formed by a small descending branch from the fourth sacral ramus and by the fifth sacral and coccygeal ventral rami. The fifth sacral ventral ramus emerges from the sacral hiatus, curves round the lateral margin of the sacrum below its cornu and pierces ischiococcygeus from below to reach its upper, pelvic surface. Here it is joined by a descending branch of the fourth sacral ventral ramus; the small trunk so formed descends on the pelvic surface of ischiococcygeus and joins the minute coccygeal ventral ramus which emerges from the sacral hiatus and curves round the lateral coccygeal margin to pierce coccygeus to reach the pelvis. The small trunk that is formed in this way is the coccygeal plexus. Anococcygeal nerves arise from it and form a few fine filaments which pierce the sacrotuberous ligament to supply the adjacent skin.

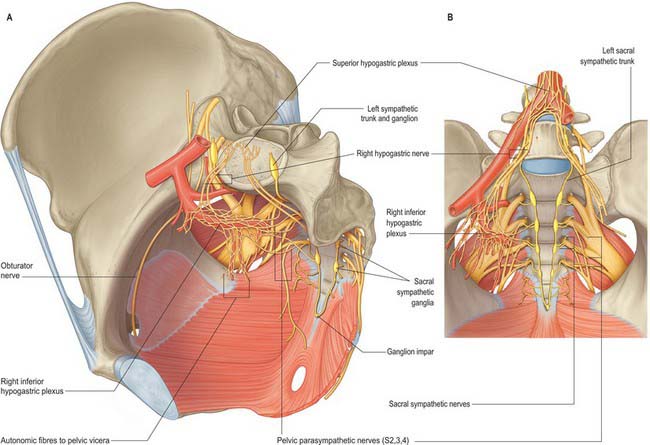

Pelvic part of the sympathetic system

The pelvic sympathetic trunk lies in the extraperitoneal tissue anterior to the sacrum beneath the presacral fascia (Fig. 63.10). It lies medial or anterior to the anterior sacral foramina and has four or five interconnected ganglia. Above, it is continuous with the lumbar sympathetic trunk. The right and left trunks converge below the lowest ganglia and unite in the small ganglion impar anterior to the coccyx. Grey rami communicantes pass from the ganglia to sacral and coccygeal spinal nerves but there are no white rami communicantes. Medial branches connect across the midline and twigs from the first two ganglia join the inferior hypogastric plexus or the hypogastric ‘nerve’. Other branches form a plexus on the median sacral artery.

PERINEUM

MUSCLES AND FASCIAE OF THE PERINEUM

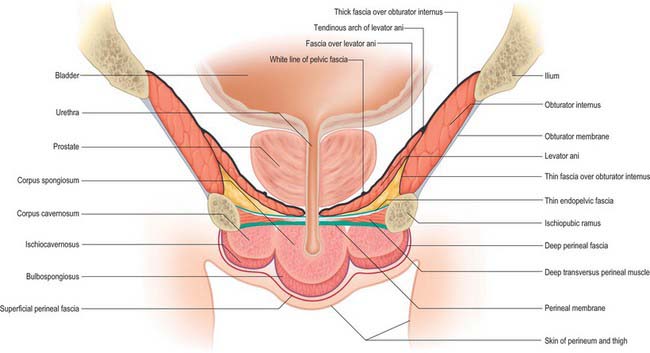

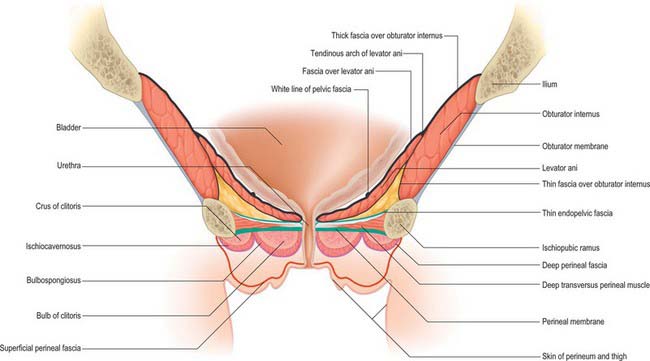

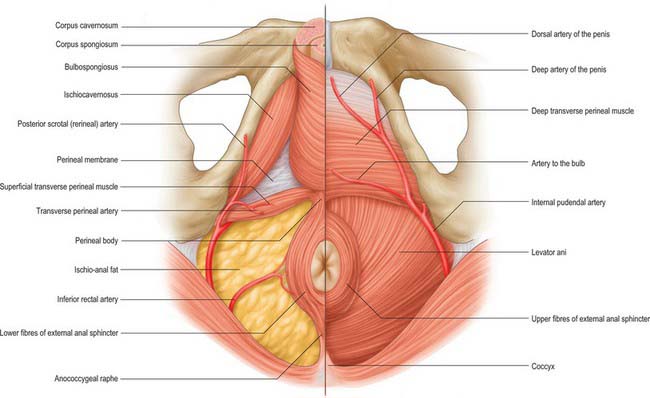

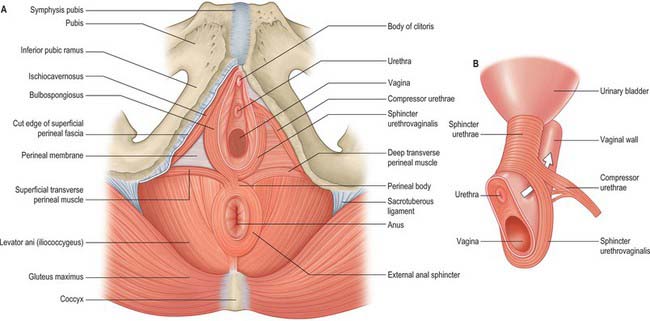

The male urogenital triangle contains the bulb and attachments of the penis (Fig. 63.11) (Ch. 76) and the female urogenital triangle contains the mons pubis, the labia majora, the labia minora, the clitoris and the vaginal and urethral orifices (Ch. 77).

Anal triangle

The structure of the anal triangle is similar in males and females, the main difference reflecting the wider transverse dimension of the triangle in females as a result of the larger size of the pelvic outlet. The anal triangle contains the anal canal and its sphincters, and the ischio-anal fossa and its contained nerves and vessels. It is lined by superficial and deep fascia.

Ischio-anal fossa

The ischio-anal fossa is an approximately horse-shoe shaped region filling the majority of the anal triangle: although often referred to as a space, it is filled with loose adipose tissue and occasional blood vessels. The ‘arms’ of the horseshoe are triangular in cross section because levator ani slopes downwards towards the anorectal junction (see Fig. 67.43). The anal canal and its sphincters lie in the centre of the horseshoe. Above them the deep medial limit of the fossa is formed by the deep fascia over levator ani. The outer boundary of the fossa is formed anterolaterally by the deep fascia over obturator internus deeply and the periosteum of the ischial tuberosities more superficially. Posterolaterally, the outer boundary is formed by the lower border of gluteus maximus and the sacrotuberous ligament. Anteriorly, the superficial boundary of the fossa is formed by the posterior aspect of the transverse perineal muscles and the deep perineal pouch. Deep to this there is no fascial boundary between the fossa and the tissues deep to the perineal membrane as far anteriorly as the posterior surface of the pubis below the attachment of levator ani. Posteriorly, the fossa contains the attachment of the external anal sphincter to the tip of the coccyx: above and below this, the adipose tissue of the fossa is uninterrupted across the midline. These continuations of the ischio-anal fossa mean that infections, tumours and fluid collections within may not only enlarge relatively freely to the side of the anal canal, but may also spread with little resistance to the opposite side and deep to the perineal membrane. The internal pudendal vessels and accompanying nerves lie in the lateral wall of the ischio-anal fossa, enclosed in fascia forming the pudendal canal. The inferior rectal vessels and nerves cross the fossa from the pudendal canal and often branch within it.

Urogenital triangle

Deep perineal pouch (space)

Urethral sphincter mechanism

The urethral sphincter mechanism consists of the intrinsic striated and smooth muscle of the urethra and the puboperinealis (pubourethralis) component of levator ani which surrounds the urethra at the point of maximum concentration of those muscles. It surrounds the membranous urethra in the male and the middle and lower thirds of the urethra in the female. In the male, fibres also reach up to the lowest part of the neck of the bladder and, between the two, lie on the surface of the prostate. The bulk of the fibres surround the membranous urethra and some fibres are attached to the inner surface of the ischiopubic ramus. In the female, the sphincter mechanism surrounds more than the middle third of the urethra. It blends above with the smooth muscle of the bladder neck and below with the smooth muscle of the lower urethra and vagina.

The urethral sphincter mechanism extends from the perineum through the urogenital hiatus into the pelvic cavity. It probably receives innervation via the perineal branch of the pudendal nerve from below and direct branches from the sacral plexus and the pelvic splanchnic nerves from above (Wendell-Smith & Wilson 1991). All these nerves originate in the second, third and fourth sacral spinal segments.

Compressor urethrae

Compressor urethrae exists in females and arises from the ischiopubic rami of each side by a small tendon. Fibres pass anteriorly to meet their contralateral counterparts in a flat band which lies anterior to the urethra, below sphincter urethrae (Fig. 63.12). A variable number of fibres from the same origin fan medially to reach the lower walls of the vagina, and may rarely reach as far posteriorly as the perineal body.

Superficial and deep perineal fasciae

Superficial and subcutaneous perineal pouches

Subcutaneous perineal pouch

The subcutaneous perineal pouch lies between the deep perineal fascia and the superficial perineal fascia. Under normal circumstances these two layers are only separated by relatively thin subcutaneous connective tissue and the skin of the anterior perineum and genitals is relatively mobile over the deeper structures. This pouch is, however, capable of expanding considerably in the presence of fluid accumulation; blood, urine or fluid collecting in the subcutaneous pouch due to trauma or surgery on the urogenital triangle will spread throughout the tissues of the triangle including the scrotum or labia majora, but cannot pass posteriorly into the anal triangle or laterally into the medial thigh due to the firm tethering of the posterior attachments of the subcutaneous fascia. Since the superficial perineal fascia is in continuity with the fascia of the anterior abdominal wall, fluid, blood or pus may also track freely between the subcutaneous tissues of the anterior abdominal wall and the subcutaneous perineal pouch (e.g. post surgical haematomas of the abdominal wall readily cause discolouration of the perineal and genital skin).

Superficial perineal pouch

The superficial perineal pouch lies below the perineal membrane and is limited superficially by the deep perineal fascia (investing fascia of the superficial perineal muscles) (Fig. 63.13). It contains the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum, ischiocavernosus, bulbospongiosus and the superficial transverse perinei, and branches of the pudendal vessels and nerves. In the female, it is crossed by the urethra and vagina and contains the clitoris. In the male, it contains the urethra as it runs in the root of the penis. It is a fully confined space; injuries to the contents of the space (such as bleeding into the urethra in the penile root) do not communicate with the deep or subcutaneous pouches unless the fascial coverings are also lacerated or breached.

Perineal body

The perineal body is a poorly defined aggregation of fibromuscular tissue located in the midline at the junction between the anal and urogenital triangles. It is attached to many structures in both the deep and superficial urogenital spaces. Posteriorly, it merges with fibres from the middle part of the external anal sphincter and the conjoint longitudinal coat. Superiorly, it is continuous with the rectoprostatic or rectovaginal septum, including fibres from levator ani (puborectalis or pubovaginalis). Anteriorly, it receives a contribution from the deep transverse perinei, the superficial transverse perinei and bulbospongiosus (Fig. 63.4). The perineal body is continuous with the perineal membrane and the superficial perineal fascia. Since the superficial perineal fascia runs forward into the skin of the perineum, the perineal body is tethered to the central perineal skin, which is often puckered over it. In males, this is continuous with the perineal raphe in the skin of the scrotum. In females, the perineal body lies directly posterior to, and is attached to, the posterior commissure of the labia majora and the introitus of the vagina.

Bulbospongiosus

Bulbospongiosus helps to empty the urethra of urine after the bladder has emptied. In the male, it may assist in the final stage of erection as the middle fibres compress the erectile tissue of the bulb and the anterior fibres contribute by compressing the deep dorsal vein of the penis. It contracts six or seven times during ejaculation, assisting in the expulsion of semen. In the female, bulbospongiosus acts to constrict the vaginal orifice and express the secretions of the greater vestibular glands. Anterior fibres contribute to erection of the clitoris by compressing its deep dorsal vein.

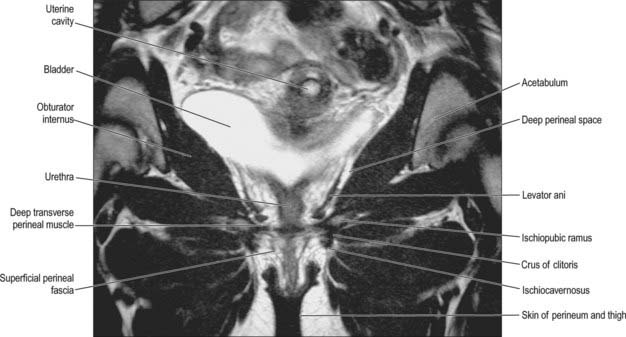

Ischiocavernosus

In the male, ischiocavernosus covers the crus penis. It is attached by tendinous and muscular fibres to the medial aspect of the ischial tuberosity behind, and to the ischial ramus on both sides of the crus. These fibres end in an aponeurosis which is attached to the sides and under surface of the crus penis. In the female, ischiocavernosus is related to a smaller crus clitoris and has a much smaller attachment to the ischiopubic ramus, but is otherwise similar to the corresponding muscle in the male (Figs 63.14, 63.15).

Fig. 63.15 Muscles and fasciae of the female perineum – coronal T2-weighted MRI.

(By courtesy of Dr J Lee and Ms K Wimpey, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London.)

VASCULAR SUPPLY AND LYMPHATIC DRAINAGE OF THE PERINEUM

Arteries of the perineum

Internal pudendal artery (in the perineum)

The internal pudendal artery enters the perineum around the posterior aspect of the ischial spine and runs on the lateral wall of the ischio-anal fossa in the pudendal (Alcock’s) canal with the pudendal veins and the pudendal nerve. The canal is formed by the connective tissue binding the vessels and nerve to the perineal surface of the obturator internus fascia and lies about 4 cm above the lower limit of the ischial tuberosity. As the artery approaches the margin of the ischial ramus, it proceeds above or below the perineal membrane, along the medial margin of the inferior pubic ramus and ends behind the inferior pubic ligament.

In the male, the internal pudendal artery distal to the perineal artery gives a branch to the bulb of the penis before it divides into the deep (cavernosal) and dorsal arteries of the penis (Fig. 63.11). Given its distribution, the internal pudendal artery distal to its perineal branch has been named the artery of the penis. The artery to the bulb supplies the corpus spongiosum and the deep artery to the penis supplies the corpus cavernosa on each side. The dorsal artery runs on the dorsal aspect of the penis, and supplies circumflex branches to the corpora cavernosa and corpus spongiosum which end by anastomosing in the coronal sulcus and supplying the glans penis and its overlying skin.

In the female, the artery to the bulb is distributed to the erectile tissue of the vestibular bulb and vagina. The cavernosal artery is much smaller and supplies the corpora cavernosa of the clitoris; the dorsal artery supplies the glans and prepuce of the clitoris (Fig. 63.11).

Doyle JF. The perforating veins of the gluteus maximus. Ir J Med Sci. 1970;3:285-288.

Smith GE. Studies in the anatomy of the human pelvis, with special reference to the fasciae and visceral supports. Part I. J Anat Physiol. 1908;42:198-218.

DeLancey JO. Structural support of the urethra as it relates to stress urinary incontinence: the hammock hypothesis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1713-1723.

Wendell-Smith CP, Wilson PM. The vulva, vagina and urethra and the musculature of the pelvic floor. In: Philipp E, Setchell M, Ginsburg J. Scientific Foundations of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1991:84-100.