Trophoblastic Disease

Understanding the process of normal implantation and the development of villi together with the role played by the trophoblast is essential for similarly comprehending aberrations caused by abnormal trophoblastic generation (Figs. 21–1 through 21–3). Anatomic, microanatomic, and physiologic changes create a spectrum of disorders referred to as trophoblastic disease.

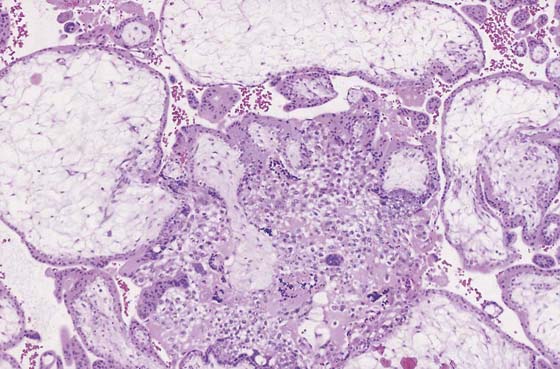

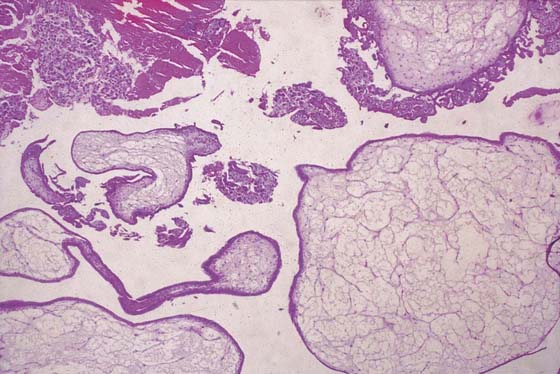

Trophoblastic disorders may be divided into benign and malignant categories (Table 21–1). In developed countries (e.g., North America, United Kingdom, Western Europe), the incidence of hydatidiform mole is 1 : 1000 pregnancies, and choriocarcinoma is seen in 1 in 30,000 pregnancies. In the Far East, the number of molar pregnancies is 3 to 10 times greater, and the risk for choriocarcinoma is 10 to 60 times greater. Moles are subdivided into complete or partial. Complete moles are characterized by extreme villous swelling (hydropic change), trophoblastic hyperplasia, and paucity of fetal blood vascular channels (Figs. 21–3 through 21–6). Complete moles result from a single 23 X sperm fertilizing a defective ovum that contains no maternal genes. As a result of subsequent endoreduplication, the mole contains 46 XX chromosomes. In the case of partial mole, two sperms fertilize an egg with 23 X chromosomes, creating a triploid mole containing 69 XXX chromosomes (Fig. 21–7).

Diagnosis is considered by a high index of suspicion based on clinical signs and symptoms of vaginal bleeding, hyperemesis, excess uterine size for gestational age, early-onset pre-eclampsia, hyperthyroidism, and intrauterine infection. The diagnosis is confirmed by viewing a passed molar vesicle, by pelvic ultrasound, by obtaining serial rising levels of serum and urine human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), and by the presence of theca-lutein cysts (Fig. 21–8).

FIGURE 21–1 Early implantation site. The deeper pink tissue is trophoblast, which is invading the decidua (light pink). Note the endometrial gland to the far left.

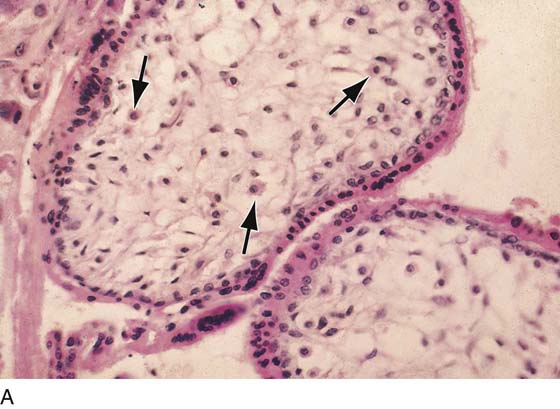

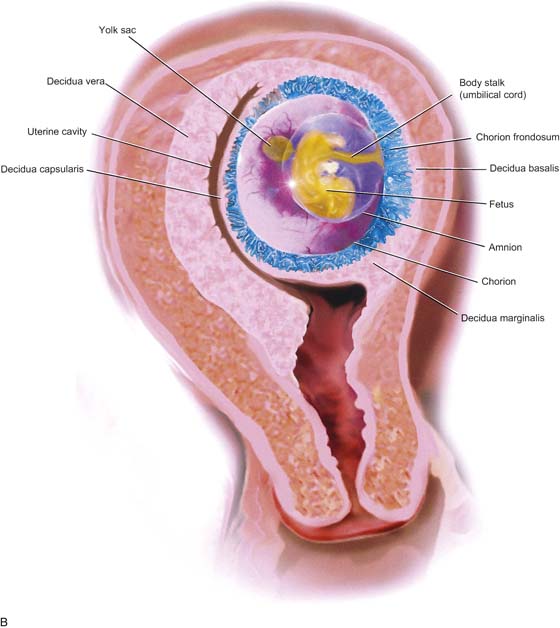

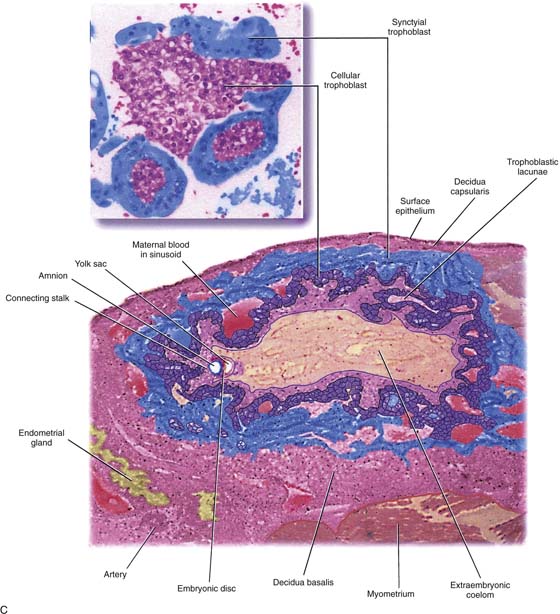

FIGURE 21–2 A. Immature villi have two layers of trophoblast surrounding the villous connective tissue core. The outer, deep pink layer is syncytiotrophoblast, whereas the inner layer is cytotrophoblast. Note the open villous vascular channels and the Hofbauer cells (arrows). B. Trophoblastic cells make up the chorion and the villi, that is, the major part of the placenta. In this picture, the chorionic tissues are shown encapsulating the developing embryo and amnion. Major invasion and development of villi occur at the decidua basalis. The peripheral chorion frondosum will atrophy to form the bald chorion (chorion laeve). C. Physiologic trophoblast exhibits many of the characteristics of the premalignant and the malignant trophoblast. In this illustration, a trophoblast is shown to invade the maternal endometrium, open up maternal blood sinuses, create vacuoles, form blood lakes, and form primitive villi. The inset shows cores of cytotrophoblast being surrounded by syncytiotrophoblast. Strikingly normal trophoblast does not destroy the maternal tissues during the invasive process, whereas malignant trophoblast creates widespread necrosis.

FIGURE 21–3 Well-developed, magnified view of a complete hydatidiform mole. The molar vesicles are fluid-filled distended villi. They can break off the main stem and be passed to the outside via the vagina, in which case the diagnosis of mole can be made with certainty. In the case of hydatidiform mole, no amnion is formed; therefore, direct entry and egress between the vagina and the uterine cavity exist.

FIGURE 21–4 Low-power view of distended, hydropic villi clustered around masses of trophoblastic cells.

FIGURE 21–5 Higher-power photomicrograph shows hydropic villi, absence of fetal vessels, and trophoblastic hyperplasia—three elements necessary to diagnose hydatidiform mole.

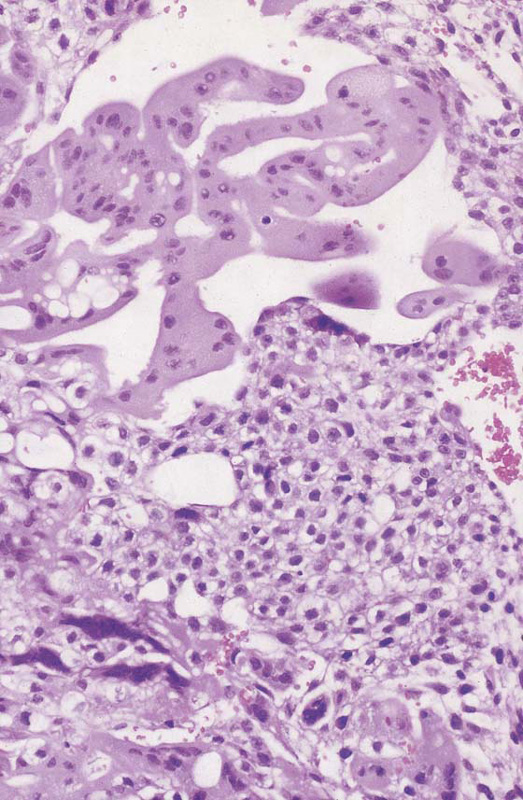

FIGURE 21–6 High-powered view of trophoblast shown in Figure 21–4. Note the proliferation of the cytotrophoblast that represents the immature, dividing trophoblast cells. Cytotrophoblasts are small cells with well-developed cell membranes. Syncytiotrophoblasts are mature cells comprising a number of cytotrophoblast cells melding to form the multinucleate syncytium. Note that individual cell membranes have been lost. Vacuole formation is commonly seen with trophoblastic proliferation and harkens back to a property of the primitive trophoblastic cells observed during normal implantation.

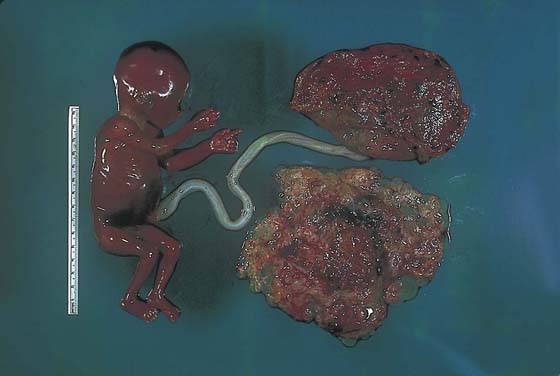

FIGURE 21–7 The rare occurrence of a twin gestation is shown, in which one entity is a mole and the other a relatively normally developed fetus.

FIGURE 21–8 Theca-lutein cysts are associated with all forms of trophoblastic disease. The theca cells of the ovarian cortex grow in response to chorionic gonadotropin, which is elaborated by both types of trophoblastic cells.

When the diagnosis has been made and confirmed, a plan should be made to evacuate the mole in a timely fashion. Hysterectomy with the mole in situ has a definite place in the management of the disorder (Fig. 21–9). The technique differs from routine hysterectomy in the following ways: The ovarian blood supply is secured before uterine manipulation; only minimal uterine manipulation is required to enable the uterine vessels to be clamped. If the blood supply is secured first, molar villous transportation will be minimized (Fig. 21–10). If future fertility is desired, then the most appropriate technique for elimination of the mole is suction curettage. Oxytocin must be flowing intravenously during this procedure; otherwise, very large volumes of blood can be lost in very short periods of time. Because most patients with hydatidiform mole have previously hemorrhaged and are suffering from anemia, additional blood loss can precipitate sudden shock. Very gentle, careful sounding should be performed before dilatation. The utmost care is required to avoid perforation. As with the sounding, cervical dilatation must be performed in the axis of the uterine position and with great care so as not to perforate. Pratt dilators are best for this stage of the procedure. A 10- or 12-mm suction curette should be utilized, and dilatation should exceed the diameter of the cannula by at least 2 mm, to allow easy movement of the suction cannula into and out of the uterus. Obviously, suction is applied only during the withdrawal movement of the cannula. Uterine size, that is, cervical/fundal height, should be frequently rechecked because it rapidly changes as the molar tissue is suctioned up. The author prefers not to follow suction with sharp curettage because this maneuver introduces the greatest risk for uterine perforation and deportation of molar villous products.

Fluid management is a key factor in the safe care of such patients because they are prone to fluid overload and pulmonary edema. Therefore, the gynecologist is well advised to limit infusions of water, lactated Ringer’s, or saline solutions. Oxytocin should be concentrated in 500 mL D5S with 20 to 50 units. Beta-blockers should be available for administration if signs of thyroid storm are observed. The patient’s hemoglobin, hematocrit, and white cell count should be checked before and after the procedure, together with electrolytes. Additionally, the patient’s intake and output should be monitored by obtaining daily weights.

Complete and partial moles should be followed up by serial hCG levels and chest radiographs. Pregnancy should be postponed during follow-up, and the author prefers administration of oral contraceptives because these are both effective and easy to administer. The advantages of oral contraceptives outweigh any theoretical disadvantages.

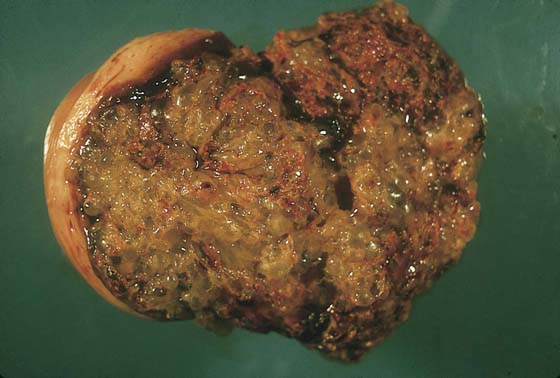

Following hysterectomy or weekly suction evacuation, hCG titers should be obtained (urine and serum) until three negative hCG titers are obtained. Then, two to four weekly hCG assays should be obtained for 3 months, followed by monthly titers for 1 year. Chest radiographs should be obtained monthly.

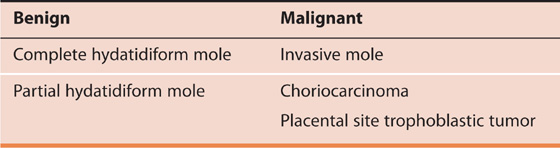

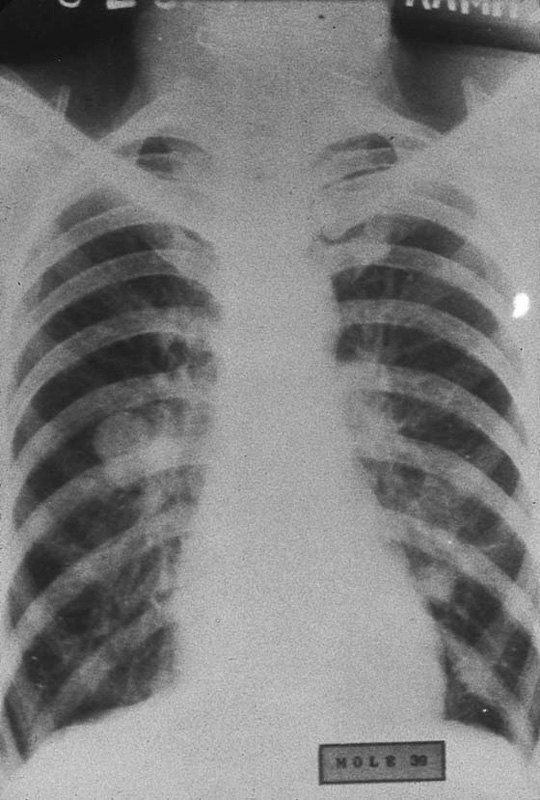

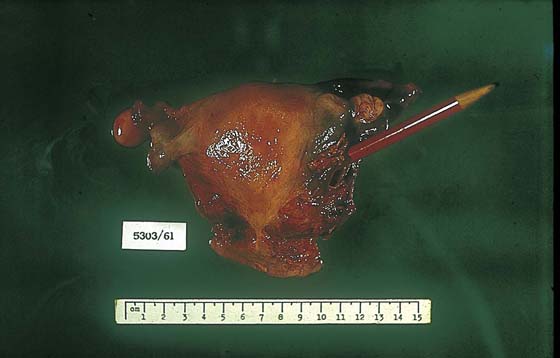

Invasive mole or choriocarcinoma is suspected with recurrence of vaginal bleeding, amenorrhea, rising or plateauing hCG titers, or pulmonary lesions on radiograph. Hysteroscopy with sampling will permit a tissue diagnosis for intrauterine lesions. Occasionally, an invasive mole will present with symptoms and signs more or less identical to those of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy (Fig. 21–11). In these cases, the invading trophoblast erodes through the uterine muscle and with attendant heavy bleeding (Figs. 21–12 and 21–13) ruptures into the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 21–14). Choriocarcinoma represents the most dedifferentiated aspect of trophoblastic disease and the most malignant phase of the disorder. The disease invades the uterine wall early (Fig. 21–15). As with hydatidiform and invasive mole, choriocarcinoma is associated with the formation of theca-lutein cysts (Fig. 21–16).

In fact, choriocarcinoma may not present with any local signs or symptoms. The first hint of its presence may be pulmonary, hepatic, or cerebral symptoms created by metastatic disease (Figs. 21–17 through 21–25). Every gynecologist should be warned about performing a biopsy of vaginal metastatic choriocarcinoma because these lesions are apt to bleed profusely and are difficult to control with suture or electrocoagulation (Fig. 21–26).

Surgery plays a significant role in the treatment of invasive mole and choriocarcinoma. Hysterectomy coupled with chemotherapy may offer the best chances of cure. Chemotherapy will create side effects. Particularly vulnerable are rapidly growing cell populations, such as bone marrow, gastrointestinal epithelium, skin, and hair.

FIGURE 21–9 Complete moles in high-risk women (e.g., women >40 years of age or of high parity) should be treated by hysterectomy with the mole in situ if future fertility is not a consideration.

FIGURE 21–10 During hysterectomy procedures for the treatment of hydatidiform mole, it is wise to secure the vascular supply at the initiation of the operation to avoid villous deportation. This radiograph shows several nodules. When sampled, the pulmonary lesions revealed benign, hydropic villi together with fibrosis. During 12-month follow-up, the pulmonary lesions spontaneously regressed.

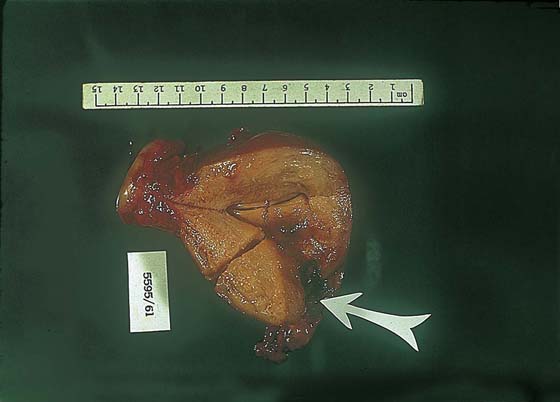

FIGURE 21–11 This invasive mole (penetrating mole) presented with signs and symptoms of a ruptured ectopic pregnancy. At laparotomy, a massive hemoperitoneum was observed. The trophoblastic tissue had, in fact, eroded through the full thickness of the uterine wall.

FIGURE 21–12 Cut view of a uterus containing an invasive mole. The arrow points to fundal destruction caused by invading trophoblastic cells.

FIGURE 21–13 High-power view of invasive molar tissue that necrosed the myometrium.

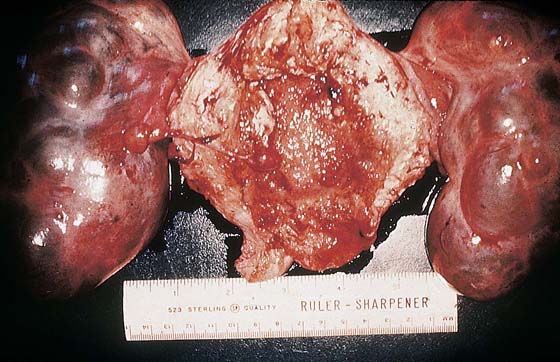

FIGURE 21–14 Theca-lutein cysts associated with an invasive mole (hysterectomy specimen). The ovaries could have been preserved because the cysts will regress after the molar tissue has been eradicated.

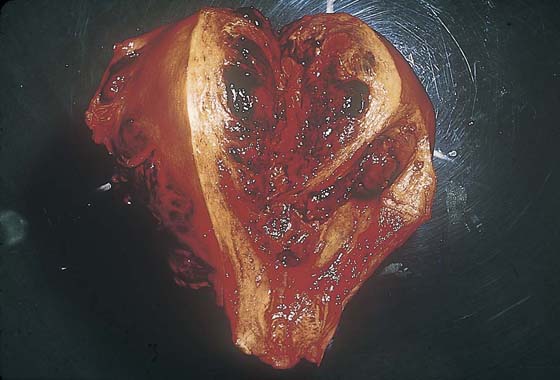

FIGURE 21–15 Cut surface of the uterus that is riddled with choriocarcinoma. Note the extensive hemorrhage. Because trophoblastic cells have the propensity to invade blood vessels, hemorrhage is usually extensive and severe in cases of choriocarcinoma.

FIGURE 21–16 Large theca-lutein cysts are also associated with choriocarcinoma involving the uterus.

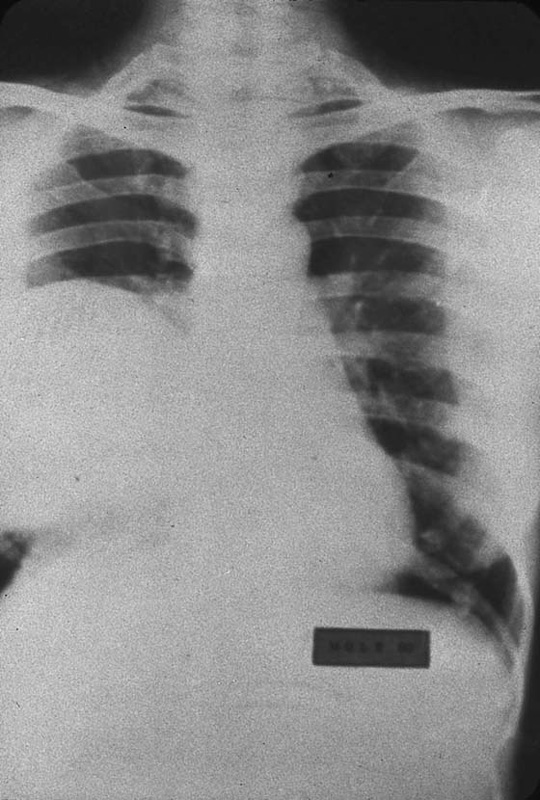

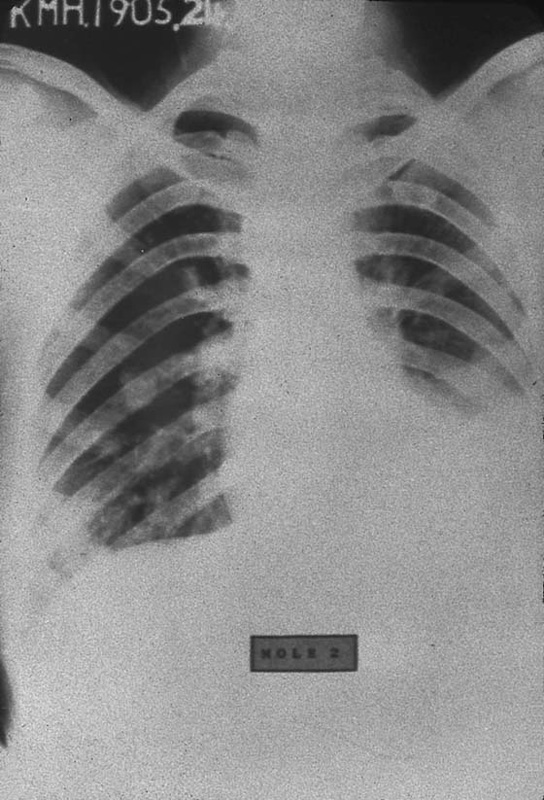

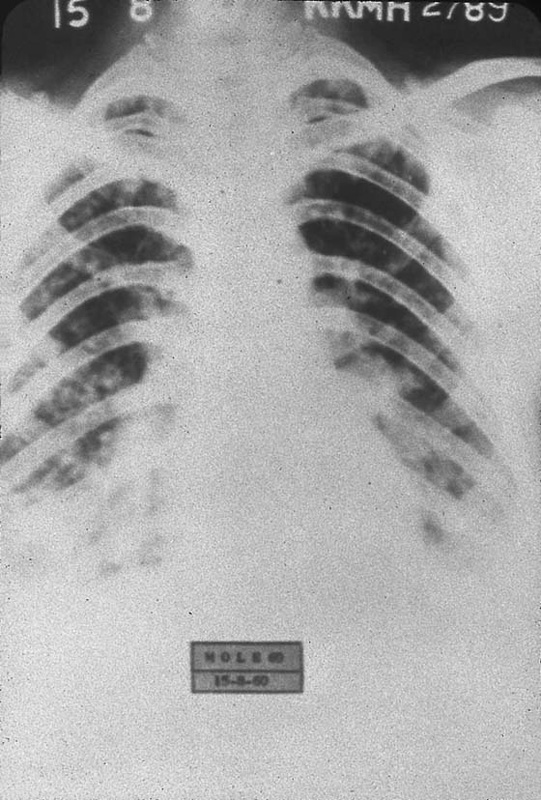

FIGURE 21–17 The most common metastatic site associated with choriocarcinoma is the lung. This radiograph shows a large, cannonball lesion occupying the greater part of the right lung.

FIGURE 21–18 Numerous pulmonary and rib metastases are seen in this case of metastatic choriocarcinoma.

FIGURE 21–19 Metastatic choriocarcinoma with miliary pattern on radiograph.

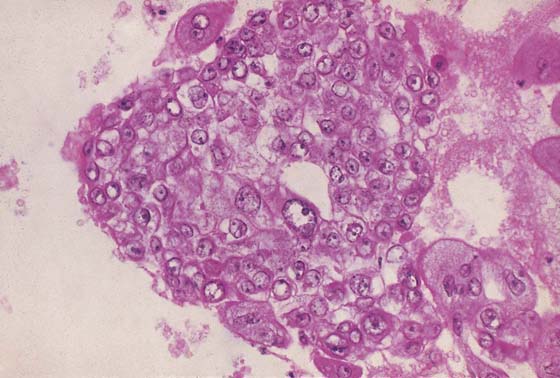

FIGURE 21–20 Choriocarcinoma is the most undifferentiated of the trophoblastic disease entities. The trophoblast cannot differentiate to form villi. Here, solid masses of mainly cytotrophoblasts are present.

FIGURE 21–21 One of the more common metastatic sites for choriocarcinoma is the vagina. Because these lesions are exceedingly vascular, great care should be exercised when a biopsy is performed.

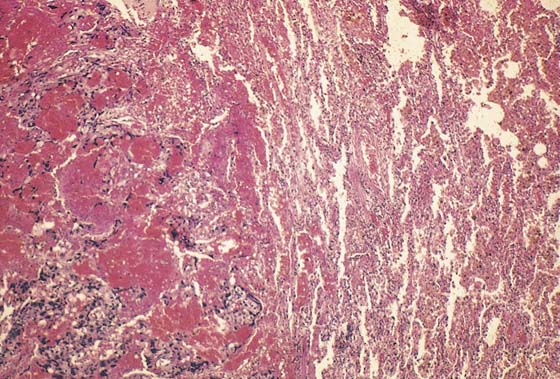

FIGURE 21–22 Postmortem specimen of the lung of a patient who died of metastatic choriocarcinoma. The lung is congested and red because of extensive hemorrhage within the lung parenchyma.

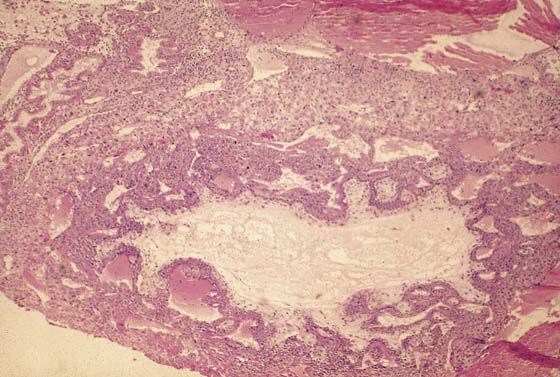

FIGURE 21–23 Histopathologic section of the lung shown in Figure 21–22. To the left is invading trophoblastic tissue surrounded by hemorrhage. To the right are congested alveoli.

FIGURE 21–24 Section of the liver showing subcapsular nodules of metastatic choriocarcinoma.

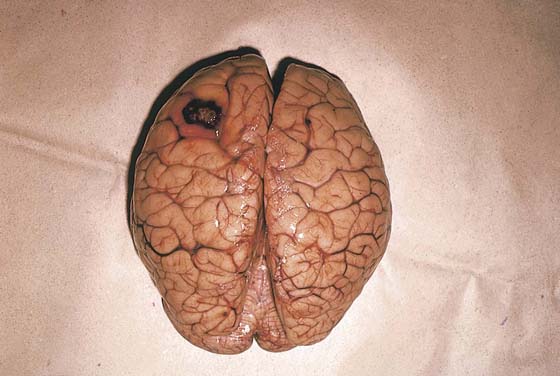

FIGURE 21–25 A metastatic trophoblastic nodule is seen on the surface of the left cerebral hemisphere.

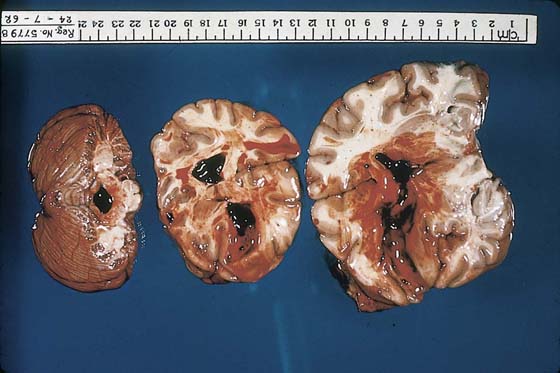

FIGURE 21–26 Cut sections of the brain show much greater damage than is perceived in Figure 21–25. Note the very large intraventricular hemorrhage, which, in fact, was the terminal event for this patient.

Classification of Trophoblastic Disorders

Classification of Trophoblastic Disorders