CHAPTER 64 TRIGEMINAL NEURALGIA AND OTHER FACIAL PAIN

HISTORICAL CONSIDERATIONS

“…such violent and exquisite torment, that it forced her to such cries and shrieks as you would expect from one upon the rack, to which I believe hers was an equal torment, which extended itself all over the right side of her face and mouth. When the fit came there was, to My Lady’s own expression of it, as it were a flash of fire all of a sudden shot into all of those parts, and at every one of those twitches which made her shriek out, her mouth was constantly drawn to the right side towards the right ear by repeated convulsive motions, which were constantly accompanied by her cries…. These violent fits terminated on a sudden and then My Lady seemed to be perfectly well….” (John Locke and Kenneth Dewhurst)1,2

Hence it should appear, that the pain, in question, does not arise from any disease in the part, but entirely a nervous affection.”2a

“In advanced cases the paroxysms follow one another rapidly and without assignable cause, and in the intervals the patient may never be quite free from pain. They are inaugurated by almost any form of external stimulus, by a draught of air, by movement of the facial muscles or of the tongue in speaking, by touching the skin, particularly over those points from which the pain seems to take its origin, by the act of swallowing, especially when the pain involves the mucous membrane field of distribution of the nerve. It is not a self-limited disease. In some instances the neuralgia reaches such a frightful intensity that it renders the patient’s life insupportable. In former years suicide was not an uncommon consequence.”3

THE CLINICAL SYNDROME

Trigeminal neuralgia is a severe, almost exclusively unilateral, neuropathic pain located within the distribution of the trigeminal nerve, manifesting as paroxysmal, high-intensity, stabbing pain lasting seconds. Each attack may be followed by a refractory period, a period of relief that lasts seconds, minutes, or even hours. The burst of pain can occur spontaneously or can be triggered by stimulating a specific area of the face, known as a trigger zone. Trigger zones can be difficult to locate: They exist anywhere within the trigeminal distribution, including intraorally. The trigger zone is located in the same division of the trigeminal nerve as the pain. For this reason, patients characteristically avoid touching the face, washing, shaving, biting, chewing, or any other maneuver that stimulates the trigger zones and produces the pain.4 This avoidance is an invaluable clue to the diagnosis. With almost every other facial pain syndrome, patients massage, abrade, or apply heat and cold to the painful area; however, in trigeminal neuralgia, exactly the opposite occurs: Patients avoid any stimulation of the face or mouth. The pain is often characterized as an “electric shock” and is typically accompanied by a unilateral grimace; hence the designation tic douloureux. The pain may occur daily for weeks or months and then cease, sometimes for years, before returning; these intervals are known as periods of remission.

Although this pain has been clinically described for centuries, the etiology of trigeminal neuralgia and the other cranial neuralgias is not fully understood. For years, the integrity of the myelin sheath has been the focal point of investigation; however, the only agreement is that there is a dysfunction of the trigeminal sensory system.5 Trigeminal neuralgia is classified as primary (idiopathic or type 1) or secondary (type 2), which is caused by compression or irritation, tumor, or disease, such as multiple sclerosis.

Intermittent trigeminal neuralgia is uncommon in multiple sclerosis, with an incidence of between 1% and 2%.6,7 Conversely, the incidence of multiple sclerosis among patients with trigeminal neuralgia is approximately 3%. Patients with multiple sclerosis and trigeminal neuralgia typically have a history of classic trigeminal neuralgia, except that the trigeminal neuralgia appears at a younger age when patients have multiple sclerosis than when the disease occurs in its idiopathic form. Some patients with multiple sclerosis present with recurrent episodes of face pain that are generally long lasting, not stabbing or lancinating, and without associated trigger zones. These patients are assumed to not have true trigeminal neuralgia but a form of atypical facial pain.

On rare occasions, trigeminal neuralgia may be a manifestation of brainstem disease and has been reported to result from pontine infarction.8 Neoplasms involving the trigeminal nerve generally produce constant neuropathic pain associated with sensory loss. Animal models have not been able to reproduce the pain of trigeminal neuralgia, and this limits clinicians’ ability to study the condition on a basic science level.

TESTING

The diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia is made from the clinical history. No medical testing is available to confirm the diagnosis; however, some authorities have mentioned a response to carbamazepine as being “diagnostic.” When the condition is found, magnetic resonance imaging is recommended, to rule out secondary causes. Typically, the neurologic examination findings are normal. Clinically, the onset of trigeminal neuralgia is generally after age 50, although it can occur at any age. Twice as many women as men are affected. There is usually no sensory loss in “idiopathic” trigeminal neuralgia as measured by ordinary sensory testing, although some clinicians refer to occasional sensory findings.9–12 In contrast, sensory disturbances in the distribution of the trigeminal nerve are relatively common when patients have multiple sclerosis or a structural lesion involving the trigeminal nerve or roots. Such sensory loss may even involve the inside of the mouth. Some clinicians have postulated that trigeminal neuralgia left untreated may become more atypical, accompanied by sensory disturbances and constant pain.13

Fromm and colleagues described 18 patients whose initial trigeminal pain was not characteristic of neuralgia but suggestive of a toothache or sinus pain and frequently lasted several hours.14 Often this pain was set off by jaw movements or by drinking hot or cold liquids. Then, at a later time, ranging from several days to 12 years, more typical trigeminal neuralgia developed in the same general area as the initial pain. Six of these patients became pain free while taking carbamazepine or baclofen. The authors designated the problem pretrigeminal neuralgia. This neuralgia must be differentiated from trigeminal tumors, atypical facial pain, atypical odontalgia, and facial migraine, among other entities. A magnetic resonance imaging scan emphasizing the middle and posterior fossae is recommended as a diagnostic study in this situation.

In rare instances, trigeminal neuralgia is accompanied by hemifacial spasm. The combination has been designated tic convulsif.15 Tic convulsif is characterized by periodic contractions of one side of the face, accompanied by great pain. It may be confused with the facial contortions on the involved side that can accompany the paroxysms of true trigeminal neuralgia.15 Painful tic convulsif is reported to be more severe in women than in men. It may begin in or around the orbicularis oculi as fine intermittent myokymia, with some spread thereafter into the muscles of the lower part of the face. On occasion, strong spasms involve all of the facial muscles on one side almost continuously. In rare cases, the face becomes weak, and some of the facial muscles atrophy. Tic convulsif is usually indicative of a tumor, ectatic dilation of the basilar artery, or a vascular malformation compressing the trigeminal and facial nerves.16

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Cluster-Tic Syndrome

Both trigeminal neuralgia and cluster headache in the same individual have been termed “clustertic syndrome.”17–23 In these cases, the entities are treated separately, and each is controlled with different medications.17,24 In some cases, surgical decompression of the trigeminal nerve has been successful in alleviating the pain.25,26 Secondary causes must be considered in all of these cases.27,28

Glossopharyngeal Neuralgia

Glossopharyngeal neuralgia is even rarer than trigeminal neuralgia. Clinically, the pain is similar to that of trigeminal neuralgia except that the distribution includes cranial nerve IX, the glossopharyngeal nerve, and the auricular (otic variety) and pharyngeal (cervical variety) branches of the vagus nerve. The pain is described as severe, transient, stabbing, or burning and is felt in the ear, the base of the tongue, the tonsillar fossa, or the area beneath the angle of the jaw, where it can be mistaken for trigeminal neuralgia affecting the third division of the trigeminal nerve. Rotation of the head, chewing, and swallowing may be triggers. The attacks of pain generally come in paroxysms and are lightning-like, but some patients have a more constant sore-throat sensation. Severe bradycardia, hypotension, or transient asystole, resulting in syncope or convulsions, may occur in some patients with glossopharyngeal neuralgia.29,30 Secondary causes must be ruled out with magnetic resonance imaging, and similar medications used for trigeminal neuralgia may work for this disorder as well.31–34

Geniculate Neuralgia

Geniculate neuralgia is an extremely painful disorder affecting the sensory part of the seventh cranial nerve, described as trigeminal neuralgia of the nervus intermedius.35 The pain is described as a severe stabbing pain deep within the ear.

Idiopathic Stabbing Headache

Idiopathic stabbing headache was first described as a “jabs and jolts syndrome” by Sjaastad and associates in 1979.36 Clinically, the pain is ultrashort, lasting less than one second; it can be located anywhere in the head but usually not in the facial region. It occurs as a stabbing pain or a series of recurring stabs. The frequency at which this occurs is extremely erratic, and there are no triggers. Idiopathic stabbing headache is a primary benign headache that is clinically relevant to the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia because nearly two thirds of patients find indomethacin to be helpful.37

Short-Lasting Unilateral Neuralgiform Headache Attacks with Conjunctival Injection and Tearing (SUNCT)

SUNCT is characterized as unilateral moderate to severe orbital stabbing pain that lasts for 5 to 250 seconds and may occur up to 40 or more times a day.38 The pain is accompanied by autonomic features, the most significant of which are the tearing and conjunctival injection. Attacks have been known to be precipitated by chewing, by swallowing, by touching of the nose or eyelids, or by certain neck movements. SUNCT is refractory to medical management and does not respond to indomethacin or traditional treatments for trigeminal neuralgia.

Atypical Facial Pain

Atypical facial pain or facial pain of unknown cause is characterized by a deep burning or aching sensation that is continuous and poorly localized. The pain may be unilateral or bilateral and does not necessarily follow the distribution of the peripheral nerves. It may be accompanied by sensory changes, such as allodynia, dysesthesia, and paresthesia.39 The usual sufferers are middle-aged women. Sleep and facial functions, such as eating and talking, are rarely affected, except when pain is intraoral. Some patients have a history of trauma or a dental or surgical procedure before the onset of pain.

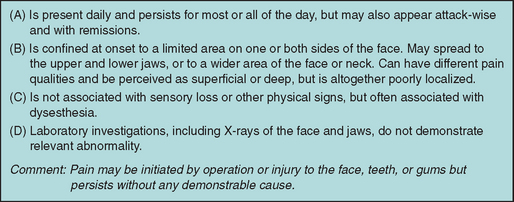

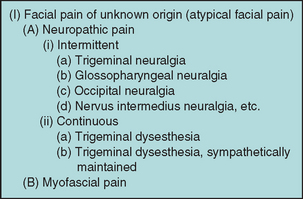

In 1993, Pfaffenrath and colleagues suggested modifying the International Headache Society diagnostic criteria for atypical facial pain (Fig. 64-1).40 Because Pfaffenrath and colleagues’ criteria could apply to pain symptoms of separate etiologies, clinicians further categorize these pains according to their specialty in hopes of a better understanding of the condition, as well as in directing treatment toward correcting the cause of the pain. Facial pain of unknown cause was also categorized by Graff-Radford, who proposed an outline to help clinicians compartmentalize their clinical findings and to create a more uniform approach to treating these disorders with limited knowledge of the etiology (Fig. 64-2).41

TREATMENT

Medical Management

Initial management of trigeminal neuralgia is medical, and surgical therapy should be considered if medical treatment fails or cannot be tolerated and if secondary causes are found during the initial workup.42,43 It is important to discuss all treatment options with the patient early in the treatment process. A neurosurgical consultation early in the medical management of the patient allows the patient time to understand the multiple treatment options. It is impossible to predict which patients may not respond to medications, and so it is imperative that they understand treatment options before desperately seeking surgery after months of failed medication trials. Patient preference for either medical or surgical treatment as first-line therapy must be a part of the decision making as well, and this can be facilitated by having an early consultation with a neurosurgeon.

If, because of side effects, the initial medication is not tolerated, then an alternative medication is employed. For example, if carbamazepine is not tolerated, other medications, including baclofen,44–50 sodium valproate,51 gabapentin,52–56 lamotrigine,58,54–61 oxcarbazepine,62–66 topiramate,62,67,68 felbamate,69 zonisamide, vigabatrin, pregabalin, and clonazepam,70,71 are sometimes effective, but the therapeutic efficacy of most of these agents has not been adequately studied formally. There is a continuing need for new antineuralgic medications because of the limited tolerance and limited efficacy of the agents already available.5

Botulinum toxin, specifically type A, has been described as effective in one case report and two open label studies.72–74 Placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed to confirm these findings. The methodology in regard to the exact location injected and the units used, as well as the duration of effect, needs to be better studied before treatment recommendations can be made.

Surgical Management

Burchiel separated the diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia into type 1 and type 2 trigeminal neuralgia.75 Type 2 cases are believed to be caused by arterial and/or venous compression of the trigeminal nerve in the area of transition from central to peripheral myelin (O-R zone) near the root entry zone of the nerve to the brainstem. Operations such as microvascular decompression directly address the underlying pathology. Microvascular decompression requires a general anesthetic and retrosigmoid craniotomy/craniectomy and therefore has historically been reserved for young, healthy patients. Other surgical interventions for trigeminal neuralgia are directed at other areas along the course of the trigeminal pathway, such as the trigeminal tracts in the brainstem, the retrogasserian nerve root, the trigeminal (gasserian) ganglion, or the peripheral trigeminal nerve distributions (V1 to V3).

Percutaneous glycerol retrogasserian rhizotomy, otherwise known as a glycerol rhizotomy, is widely used for patients with type 1, type 2, or multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia. Historically, this procedure was done with absolute alcohol75,76 or phenol and subsequently with a phenol/glycerol mixture injected into the trigeminal cistern. Subsequently, Hakanson reported that glycerol alone (without phenol) could relieve facial pain with less facial sensory loss.77

Approximately 90% of patients achieved complete/immediate pain relief after glycerol injection, and 77% maintained good/excellent pain control over an approximately 10-year follow-up.78,79 Facial sensory loss may occur after glycerol rhizotomy; its severity is mild in 32% to 48%, moderate in 13%, and dense in 6%.79,80 Facial dysesthesia has been reported in approximately 2% to 22% of patients79 and anesthesia dolorosa in fewer than 1%.80 Transient perioral herpes outbreak is seen in 3.8% to 37% of patients up to 1 week postoperatively.79,80 Aseptic meningitis has been reported in 0.6% to 1.5% of patients.79,80 Intraoperative vasovagal response can occur in 15% to 20% of cases but does not usually necessitate aborting of the procedure.80,81

Percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal nerve is based on the concept of squeezing, manipulating, or compressing the trigeminal nerve. Surgeons in the 1950s and 1960s reported that patients in whom the trigeminal nerve was traumatized during surgery seemed to have a better outcome with regard to pain relief. In 1983, Mullan and Lichtor reported a percutaneous technique for compression of the gasserian ganglion by a Fogarty catheter.81 Percutaneous balloon compression is mainly indicated for patients with type 1 or 2 (classic or idiopathic) trigeminal neuralgia and multiple sclerosis-related trigeminal neuralgia.

Pain relief is immediate in 92% to 100% of patients, and reported recurrence rates are 19% to 32% over 5 to 20 years.82,83 Severe sensory loss or dysesthesias occur in 3% to 20% of patients.82,83 Masseter or jaw weakness occurs in 3% to 16% of patients, although most such cases improve or resolve after 1 year.82,83 Transient diplopia has been reported to occur in 1.6% of patients.83 To our knowledge, corneal anesthesia and anesthesia dolorosa have not been reported.

A mild paresthesia in the distribution of the facial pain is the goal of radiofrequency treatment. Significant dysesthesia or sensory loss is reported in approximately 6% to 28% of patients, and loss of the corneal reflex may occur in 3% to 8% of patients, depending on the technique employed.84–86 In treatment of ophthalmic-distribution trigeminal neuralgia, the risk of corneal anesthesia and keratitis is certainly greater. Trigeminal nerve motor weakness has been reported after radiofrequency treatment in up to 14% of patients; however, it is most often mild and transient.84–86 The risk of anesthesia dolorosa has been reported in 0.5% to 1.6% of patients.84–86 Rare complications of carotid artery injury, stroke, diplopia, meningitis, seizures, and death have been reported.

After radiofrequency, 88% to 99% of patients obtain immediate pain relief; recurrence rates of 20% to 27% over 9- to 14-year follow-ups have been reported.84,85 Patients with a more dense sensory loss from the radiofrequency lesion have a lower recurrence rate but are subject to greater complications from dysesthesias and analgesia. One clinician reported that after recurrence of pain, 81% of patients obtained “good or excellent” pain relief with a second radiofrequency treatment.84

Although GKRS can be performed with the patient under general anesthesia, a particular advantage of this technique is that it can be done with minimal intravenous sedation. Drawbacks are the cost of purchasing and maintaining the radiosurgery device and the latency period between treatment and facial pain improvement. Pain relief typically occurs after a latency period of 4 to 12 weeks after treatment; a range of 1 day to 13 months after treatment has been reported. The rates of pain control and recurrence of trigeminal neuralgia have been rather variable between reports. The variability probably results from the use of different pain scales to report outcome, follow-up duration, number of patients unavailable for follow-up, prior surgical treatment, the size and placement of the radiation dosage, and the maximal radiation dose. An excellent response (complete pain relief without medication) and a good response (50% to 90% improved pain with or without medication) can be achieved in 57% to 86% of patients at 1 year after radiosurgery treatment.87,88 As with most surgical treatments for trigeminal neuralgia, recurrence of facial pain after GKRS increases with time after treatment. Pain recurrence rates of 23%, 33%, 39%, and 44% have been reported 1, 2, 3, and 5 years after radiosurgery treatment, respectively.89,90 Mild or tolerable facial numbness occurs in 25% to 29% of patients, and significant numbness or dysesthesia can occur in 12% to 18% of patients.87,91 Complications of facial weakness, trigeminal motor weakness, and anesthesia dolorosa have not been reported. Greater doses of radiation are correlated with both higher rates of pain control and higher rates of complications, which consist mostly of facial numbness and bothersome facial dysesthesias. Patients who experience more facial numbness seem to have a better chance of pain control.87 Repeat radiosurgery for patients with recurrent pain has also been reported, with approximately 50% excellent or good pain relief and an increased rate of facial sensory loss within a limited follow-up period.92 Longterm follow-up studies of more than 10 to 20 years are needed. The ideal Gamma knife dose and treatment strategy, as well as the role of other radiosurgery modalities, such as linear accelerator, remain to be determined.

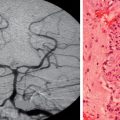

Microvascular decompression is the only medical or surgical intervention that directly addresses the presumed underlying pathology of classic trigeminal neuralgia: focal vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve near the brainstem root entry zone. The procedure requires a general anesthetic. With the use of the intraoperative microscope, the arachnoid membrane surrounding the trigeminal nerve is opened, and the nerve is explored from the brainstem to the entrance of the nerve to Meckel’s cave, where the trigeminal nerve ganglion (gasserian ganglion) is located. Under microscopic and endoscopic visualization, microdissection is performed to mobilize any arteries or veins compressing the trigeminal nerve. One or more Teflon sponges are then placed between the dissected blood vessels and the trigeminal nerve to prevent continued vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve. Veins compressing the trigeminal nerve can frequently be cauterized and divided. The compression is usually arterial, most commonly a branch of the superior cerebellar artery.93 However, venous compression alone or a combination of arterial and venous compression may also occur.94,95

When offending vessels are identified and decompressed, most patients obtain immediate relief from their facial pain. Rates of immediate pain relief as high as 90% to 98% have been reported after microvascular decompression. Barker and associates reported Jannetta’s large series of microvascular decompression procedures with up to 10-year follow-ups and defined outcome as “excellent” if at least 98% pain relief was achieved without the need for medications and “good” if at least 75% pain relief was achieved with only intermittent need for pain medication.96 In that series, an excellent or good early postoperative outcome was achieved in 98% of patients. This number decreased to approximately 84% and 67% after 1- and 10-year follow-ups, respectively. Tronnier and coworkers reported that 64% of their patients were pain free 20 years after microvascular decompression.97 Whether there is continued recurrence of facial pain with time is debated. Some clinicians have reported the majority of recurrences early (within 2 years after microvascular decompression), whereas others have reported a more constant rate of recurrence at 3.5% annually in one series.98,99

Surgical complications associated with microvascular decompression have diminished since brainstem and cranial nerve intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring has been in regular use. Complications of microvascular decompression may include cerebellar injury (0.45%), transient facial numbness (15%), mild persistent facial numbness (12%), significant facial numbness (1.6%), facial dysesthesia (0% to 3.5%), hearing loss (<1%), transient or permanent facial weakness (<1%), cerebrospinal fluid leakage (1.5% to 2.5%), hematoma (0.5%), and mortality (0.3%).93,100,101 Lower morbidity rates have been reported from high-volume centers and from surgeons performing a large number of procedures.101

When no arterial or venous compression is identified, the trigeminal nerve may be “traumatized” by stroking or squeezing the nerve with microinstruments; however, the resulting pain relief is only temporary, and such manipulation can be associated with trigeminal dysesthesias. Some surgeons have advocated partial sectioning of the sensory portion of the trigeminal nerve for negative-yield explorations or during repeat surgical exploration of the nerve for recurrent pain after microvascular decompression.98,102,103

CONCLUSIONS

Fisher A, Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Trigeminal neuralgia: current treatments and future developments. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8:123-143.

Lovely TJ, Jannetta PJ. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Surgical technique and longterm results. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:11-29.

1 Locke J. The celebrated Locke as a physician. Lancet. 1829;2:367.

2 Locke J. Letters to Dr. Mapletoft: Letter VII, Paris, 9th August 1677; Letters IX and X, Paris, 4th December 1677. Eur Magazine. 1789; (February);85:185-190. 186.

2a Hunter J. A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth: Intended as a Supplement to the Natural History of Those Parts. London: J. Johnson, 1778.

3 Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine, 8th ed. New York: Appleton, 1912.

4 Dalessio DJ. Trigeminal neuralgia. A practical approach to treatment. Drugs. 1982;24:248-255.

5 Fisher A, Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Trigeminal neuralgia: current treatments and future developments. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2003;8:123-143.

6 Harris W. Rare forms of paroxysmal trigeminal neuralgia, and their relation to disseminated sclerosis. BMJ. 1950;2:1015-1019.

7 Hooge JP, Redekop WK. Trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1995;45(7):1294-1296.

8 Kim JS, Kang JH, Lee MC. Trigeminal neuralgia after pontine infarction. Neurology. 1998;51:1511-1512.

9 Dubner R, Sharav Y, Gracely RH, et al. Idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: sensory features and pain mechanisms. Pain. 1987;31:23-33.

10 Terrence CF. Differential diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. In: Fromm GH, editor. The Medical and Surgical Management of Trigeminal Neuralgia. New York: Futura; 1987:43-63.

11 Nurmikko TJ. Altered cutaneous sensation in trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:523-527.

12 Sinay VJ, Bonamico LH, Dubrovsky A. Subclinical sensory abnormalities in trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:541-544.

13 Burchiel KJ, Slavin KV. On the natural history of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:152-154.

14 Fromm GH, Graff-Radford SB, Terrence CF, et al. Pretrigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1990;40:1493-1495.

15 Cushing H. The major trigeminal neuralgias and their surgical treatment, based on experiences with 332 gasserian operations. The varieties of facial neuralgia. Am J Med Sci. 1920;160:157.

16 Harsh GR, Wilson CB, Hieshima GB, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of vertebrobasilar ectasia in tic convulsif. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:999-1003.

17 Monzillo PH, Sanvito WL, Peres MF. [Clustertic syndrome: two case reports]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1996;54:284-287.

18 Monzillo PH, Sanvito WL, Da Costa AR. Clustertic syndrome: report of five new cases. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2000;58:518-521.

19 Mulleners WM, Verhagen WI. Clustertic syndrome. Neurology. 1996;47:302.

20 Alberca R, Ochoa JJ. Clustertic syndrome. Neurology. 1994;44:996-999.

21 Klimek A. Clustertic syndrome. Cephalalgia. 1987;7:161-162.

22 Klimek A. [“Clustertic syndrome” with a report of our case]. Neurol Neurochir Pol. 1987;21:161-163.

23 Watson P, Evans R. Clustertic syndrome. Headache. 1985;25:123-126.

24 Pascual J, Berciano J. Relief of clustertic syndrome by the combination of lithium and carbamazepine. Cephalalgia. 1993;13:205-206.

25 Kreiner M. Use of streptomycin-lidocaine injections in the treatment of the clustertic syndrome. Clinical perspectives and a case report. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 1996;24:289-292.

26 Solomon S, Apfelbaum RI, Guglielmo KM. The clustertic syndrome and its surgical therapy. Cephalalgia. 1985;5:83-89.

27 Leone M, Curone M, Mea E, et al. Clustertic syndrome resolved by removal of pituitary adenoma: the first case. Cephalalgia. 2004;24:1088-1089.

28 Ochoa JJ, Alberca R, Canadillas F, et al. Clustertic syndrome and basilar artery ectasia: a case report. Headache. 1993;33:512-513.

29 Ferrante L, Artico M, Nardacci B, et al. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia with cardiac syncope. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:58-63.

30 Ozenci M, Karaoguz R, Conkbayir C, et al. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia with cardiac syncope treated by glossopharyngeal rhizotomy and microvascular decompression. Europace. 2003;5:149-152.

31 Luef G, Poewe W. Oxcarbazepine in glossopharyngeal neuralgia: clinical response and effect on serum lipids. Neurology. 2004;63:2447-2448.

32 Rozen TD. Trigeminal neuralgia and glossopharyngeal neuralgia. Neurol Clin. 2004;22:185-206.

33 Saviolo R, Fiasconaro G. Treatment of glossopharyngeal neuralgia by carbamazepine. Br Heart J. 1987;58:291-292.

34 Ringel RA, Roy EPIII. Glossopharyngeal neuralgia: successful treatment with baclofen. Ann Neurol. 1987;21:514-515.

35 Pulec JL. Geniculate neuralgia: diagnosis and surgical management. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:955-964.

36 Sjaastad O, Egge K, Horven I, et al. Chronic paroxysmal hemicranial: mechanical precipitation of attacks. Headache. 1979;19:31-36.

37 Pareja JA, Ruiz J, de Isla C, et al. Idiopathic stabbing headache (jabs and jolts syndrome). Cephalalgia. 1996;16:93-96.

38 Sjaastad O, Saunte C, Salvesen R, et al. Shortlasting unilateral neuralgiform headache attacks with conjunctival injection, tearing, sweating, and rhinorrhea. Cephalalgia. 1989;9:147-156.

39 Turp JC, Gobetti JP. Trigeminal neuralgia versus atypical facial pain. A review of the literature and case report. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1996;81:424-432.

40 Pfaffenrath V, Rath M, Pollmann W, et al. Atypical facial pain—application of the IHS criteria in a clinical sample. Cephalalgia. 1993;13(Suppl 12):84-88.

41 Graff-Radford SB. Facial pain. Curr Opin Neurol. 2000;13:291-296.

42 Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Drugs used in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1992;74:439-450.

43 Sidebottom A, Maxwell S. The medical and surgical management of trigeminal neuralgia. J Clin Pharm Ther. 1995;20:31-35.

44 Parmar BS, Shah KH, Gandhi IC. Baclofen in trigeminal neuralgia—a clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res. 1989;1:109-113.

45 Fromm GH, Terrence CF. Comparison of L-baclofen and racemic baclofen in trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1987;37:1725-1728.

46 Baker KA, Taylor JW, Lilly GE. Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: use of baclofen in combination with carbamazepine. Clin Pharm. 1985;4:93-96.

47 Hershey LA. Baclofen in the treatment of neuralgia. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:905-906.

48 Fromm GH, Terrence CF, Chattha AS. Baclofen in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: double-blind study and longterm follow-up. Ann Neurol. 1984;15:240-244.

49 Steardo L, Leo A, Marano E. Efficacy of baclofen in trigeminal neuralgia and some other painful conditions. A clinical trial. Eur Neurol. 1984;23:51-55.

50 Fromm GH, Terrence CF, Chattha AS, et al. Baclofen in trigeminal neuralgia: its effect on the spinal trigeminal nucleus: a pilot study. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:768-771.

51 Peiris JB, Perera GL, Devendra SV, et al. Sodium valproate in trigeminal neuralgia. Med J Aust. 1980;2:278.

52 Cheshire WPJr. Defining the role for gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: a retrospective study. J Pain. 2002;3:137-142.

53 Solaro C, Messmer UM, Uccelli A, et al. Low-dose gabapentin combined with either lamotrigine or carbamazepine can be useful therapies for trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2000;44:45-48.

54 Carrazana EJ, Schachter SC. Alternative uses of lamotrigine and gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1998;50:1192.

55 Sist T, Filadora V, Miner M, et al. Gabapentin for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: report of two cases. Neurology. 1997;48:1467.

56 Khan OA. Gabapentin relieves trigeminal neuralgia in multiple sclerosis patients. Neurology. 1998;51:611-614.

57 Leandri M, Lundardi G, Inglese M, et al. Lamotrigine in trigeminal neuralgia secondary to multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2000;247:556-558.

58 Canavero S, Bonicalzi V. Lamotrigine control of trigeminal neuralgia: an expanded study. J Neurol. 1997;244:527.

59 Lunardi G, Leandri M, Albano C, et al. Clinical effectiveness of lamotrigine and plasma levels in essential and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1997;48:1714-1717.

60 Canavero S, Bonicalzi V, Ferroli P, et al. Lamotrigine control of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:646.

61 Zakrzewska JM, Chaudhry Z, Nurmikko TJ, et al. Lamotrigine (Lamictal) in refractory trigeminal neuralgia: results from a double-blind placebo controlled crossover trial. Pain. 1997;73:223-230.

62 Solaro C, Uccelli MM, Brichetto G, et al. Topiramate relieves idiopathic and symptomatic trigeminal neuralgia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;21:367-368.

63 Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Longterm cohort study comparing medical (oxcarbazepine) and surgical management of intractable trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2002;95:259-266.

64 Grant SM, Faulds D. Oxcarbazepine. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in epilepsy, trigeminal neuralgia and affective disorders. Drugs. 1992;43:873-888.

65 Patsalos PN, Elyas AA, Zakrzewska JM. Protein binding of oxcarbazepine and its primary active metabolite, 10-hydroxycarbazepine, in patients with trigeminal neuralgia. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;39:413-415.

66 Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Oxcarbazepine: a new drug in the management of intractable trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1989;52:472-476.

67 Gilron I, Booher SL, Rowan JS, et al. Topiramate in trigeminal neuralgia: a randomized, placebo-controlled multiple crossover pilot study. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2001;24:109-112.

68 Zvartau-Hind M, Din MU, Gilani A, et al. Topiramate relieves refractory trigeminal neuralgia in MS patients. Neurology. 2000;55:1587-1588.

69 Cheshire WP. Felbamate relieved trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 1995;11:139-142.

70 Caccia MR. Clonazepam in facial neuralgia and cluster headache. Clinical and electrophysiological study. Eur Neurol. 1975;13:560-563.

71 de Negrotto OV, Dalmas JF, Negrotto A. [Trigeminal neuralgia. Treatment with clonazepam]. Acta Neurol Latinoam. 1974;20:139-145.

72 Piovesan EJ, Teive HG, Kowacs PA, et al. An open study of botulinum-A toxin treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 2005;65:1306-1308.

73 Turk U, Ilhan S, Alp R, et al. Botulinum toxin and intractable trigeminal neuralgia. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2005;28:161-162.

74 Allam N, Brasil-Neto JP, Brown G, et al. Injections of botulinum toxin type a produce pain alleviation in intractable trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:182-184.

75 Burchiel KJ. A new classification for facial pain. Neurosurgery. 2003;53:1164-1166.

76 Hartel F. Uber die intracranielle Injektionbehandlung der Trigeminusneuralgie. Med Klin. 1914;10:582.

77 Hakanson S. Trigeminal neuralgia treated by the injection of glycerol into the trigeminal cistern. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:638-646.

78 Young RF. Glycerol rhizolysis for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:39-45.

79 Jho HD, Lunsford LD. Percutaneous retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy. Current technique and results. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:63-74.

80 Blomstedt PC, Bergenheim AT. Technical difficulties and perioperative complications of retrogasserian glycerol rhizotomy for trigeminal neuralgia. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2002;79:168-181.

81 Mullan S, Lichtor T. Percutaneous microcompression of the trigeminal ganglion for trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1983;59:1007-1012.

82 Brown JA, Gouda JJ. Percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal nerve. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:53-62.

83 Skirving DJ, Dan NG. A 20-year review of percutaneous balloon compression of the trigeminal ganglion. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:913-917.

84 Nugent GR. Radiofrequency treatment of trigeminal neuralgia using a cordotomy-type electrode. A method. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:41-52.

85 Taha JM, Tew JMJr. Treatment of trigeminal neuralgia by percutaneous radiofrequency rhizotomy. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:31-39.

86 Kanpolat Y, Savas A, Bekar A, et al. Percutaneous controlled radiofrequency trigeminal rhizotomy for the treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: 25-year experience with 1,600 patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:524-532.

87 Pollock BE, Phuong LK, Gorman DA, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:347-353.

88 Kondziolka D, Lunsford LD, Flickinger JC. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:42-47.

89 Petit JH, Herman JM, Nagda S, et al. Radiosurgical treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: evaluating quality of life and treatment outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2003;56:1147-1153.

90 Maesawa S, Salame C, Flickinger JC, et al. Clinical outcomes after stereotactic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:14-20.

91 McNatt SA, Yu C, Giannotta SL, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2005;56:1295-1301.

92 Hasegawa T, Kondziolka D, Spiro R, et al. Repeat radiosurgery for refractory trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:494-500.

93 Lovely TJ, Jannetta PJ. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Surgical technique and longterm results. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1997;8:11-29.

94 Lee SH, Levy EI, Scarrow AM, et al. Recurrent trigeminal neuralgia attributable to veins after microvascular decompression. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:356-361.

95 Matsushima T, Huynh-Le P, Miyazono M. Trigeminal neuralgia caused by venous compression. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:334-337.

96 Barker FG, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, et al. The longterm outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1077-1083.

97 Tronnier VM, Rasche D, Hamer J, et al. Treatment of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia: comparison of longterm outcome after radiofrequency rhizotomy and microvascular decompression. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:1261-1267.

98 Burchiel KJ, Clarke H, Haglund M, et al. Longterm efficacy of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:35-38.

99 Elias WJ, Burchiel KJ. Trigeminal neuralgia and other neuropathic pain syndromes of the head and face. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2002;6:115-124.

100 McLaughlin MR, Jannetta PJ, Clyde BL, et al. Microvascular decompression of cranial nerves: lessons learned after 4400 operations. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:1-8.

101 Kalkanis SN, Eskandar EN, Carter BS, et al. Microvascular decompression surgery in the United States, 1996 to 2000: mortality rates, morbidity rates, and the effects of hospital and surgeon volumes. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1251-1261.

102 Klun B. Microvascular decompression and partial sensory rhizotomy in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: personal experience with 220 patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:49-52.

103 Bederson JB, Wilson CB. Evaluation of microvascular decompression and partial sensory rhizotomy in 252 cases of trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:359-367.