Chapter 9 Tricuspid Valve

Introduction

The tricuspid valve is the largest of the four heart valves and ranges from 4 to 6 cm2 in area. The tricuspid valve has anterior, septal, and posterior leaflets. The anterior leaflet usually is the largest, with a width of 2.2 cm. The septal and posterior leaflets are notably smaller and measure roughly 1.5 and 2.0 cm, respectively, based on autopsy series.1 Our experience shows that the posterior leaflet often is the smallest. In many cases, the posterior leaflet is not only the smallest, it is also quite rudimentary. Disease processes of the tricuspid valve are relatively uncommon. The tricuspid valve can frequently be incompetent because of factors separate from the valve itself. Specific examples of such incompetence include right ventricular annular dilation, tricuspid annular dilation, or both as well as pulmonary hypertension. In the presence of pathology that directly involves the valve, such as bacterial endocarditis or tricuspid valve prolapse, identification of specific leaflet involvement often is critical for addressing surgical management, particularly to determine whether tricuspid valve replacement would be indicated compared with tricuspid annuloplasty.2

Advantages of Real-Time Three-Dimensional Echocardiography

Tricuspid Valve Pathology

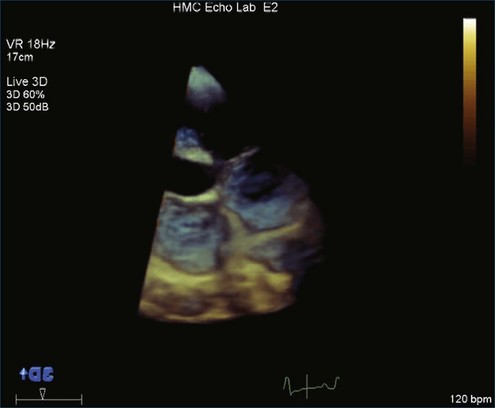

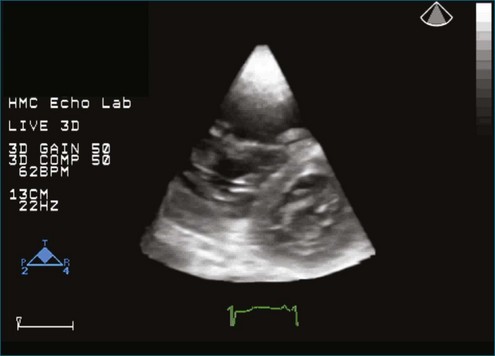

Tricuspid stenosis is a rare pathology virtually always caused by rheumatic heart disease, especially in adults. Congenital tricuspid atresia is seen in complex congenital heart disease but is not covered in this chapter. There have now been several reports of tricuspid stenosis caused by pacemaker leads.3 An example of tricuspid stenosis is shown in Figure 9-1 (Video 9-1).

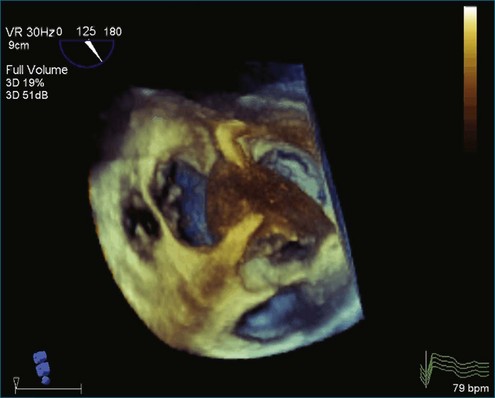

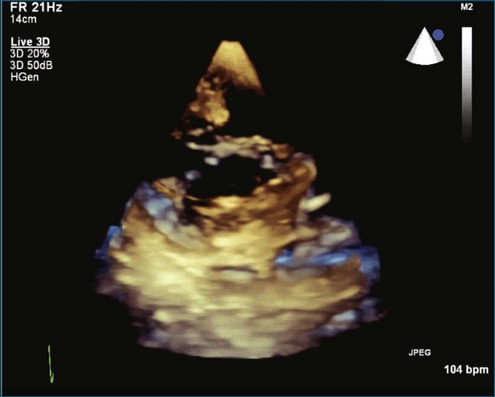

Flail tricuspid valve leaflet has become a fairly frequently detected problem, especially in tertiary centers with transplantation programs, where the tricuspid valve frequently is damaged in the process of right ventricular biopsy. Rheumatic tricuspid valve disease rarely results in the tethering of the valve leaflets so profoundly as to prevent coaptation.4–6 This problem is a frequent outcome in carcinoid triscupid valve disease (Figure 9-2; Video 9-2). Tricuspid regurgitation is a not-infrequent complication of right ventricular pacemakers, with the wire causing the regurgitation by perforating a leaflet or by pinning one of the leaflets open. Tricuspid regurgitation is common and even normal when it is mild. Tricuspid regurgitation frequently is seen as a result of primary or secondary pulmonary hypertension. Although any left heart abnormality can cause secondary pulmonary hypertension, mitral valve disease is particularly common, resulting in tricuspid regurgitation.

Transthoracic Versus Transesophageal Real-Time Three-Dimensional Echocardiography

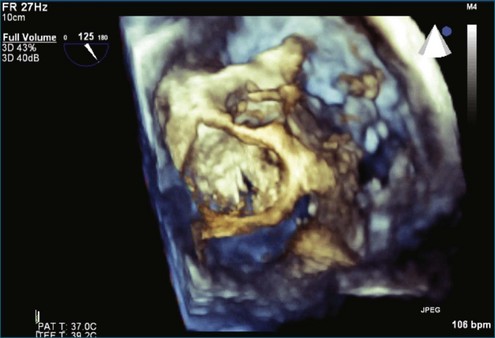

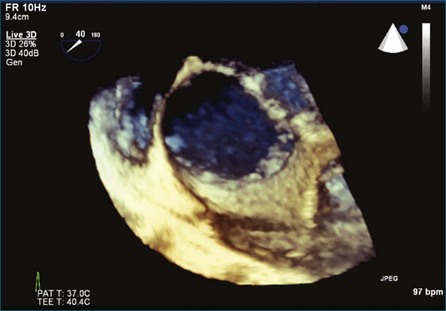

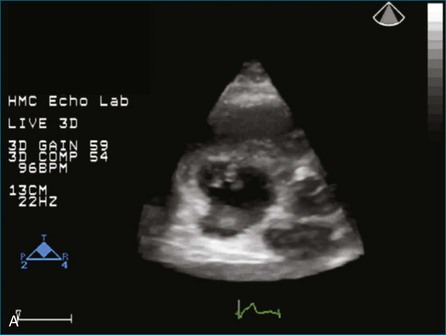

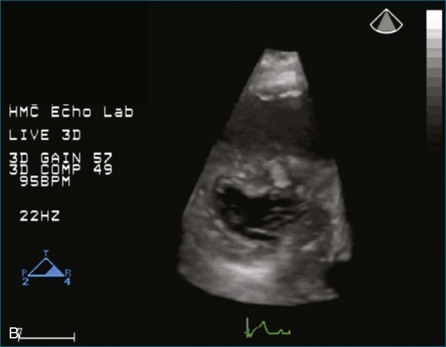

In marked contrast to the aortic valve, and particularly the mitral valve, obtaining satisfactory images from the transesophageal approach in the tricuspid valve has been found to be more challenging. 2D images of the tricuspid valve are of only fair quality by transesophageal echocardiography (TEE), and 3D images have a similar problem; although the images may be diagnostic, there is significant echo dropout of the tricuspid leaflets. However, this can be overcome by optimizing the 2DTEE images for the best possible tricuspid imaging before moving to the 3D mode: 3D zoom, live 3D, or 3D full volume. Figure 9-2 shows a 3DTEE image of the pacemaker wire traversing through the tricuspid valve. An example of a tricuspid valve vegetation imaged by RT3DTEE is shown in Figure 9-3 (Video 9-3). In this case, the patient has a vegetation on both the mitral valve and the tricuspid valve. Both Figures 9-1 and 9-2 illustrate a constant in RT3DTEE imaging. Even in cases in which the image has been optimized to show the tricuspid valve, the left-sided valves typically are more optimally visualized.

Clinical Vignettes Describing Use of Real-Time Three-Dimensional Echocardiography for Tricuspid Valve Imaging

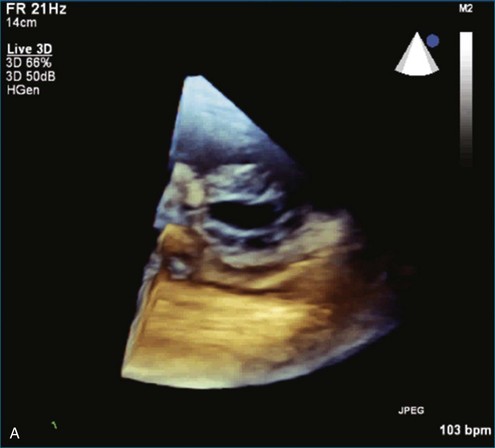

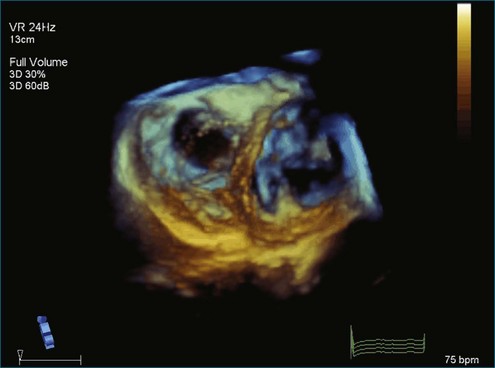

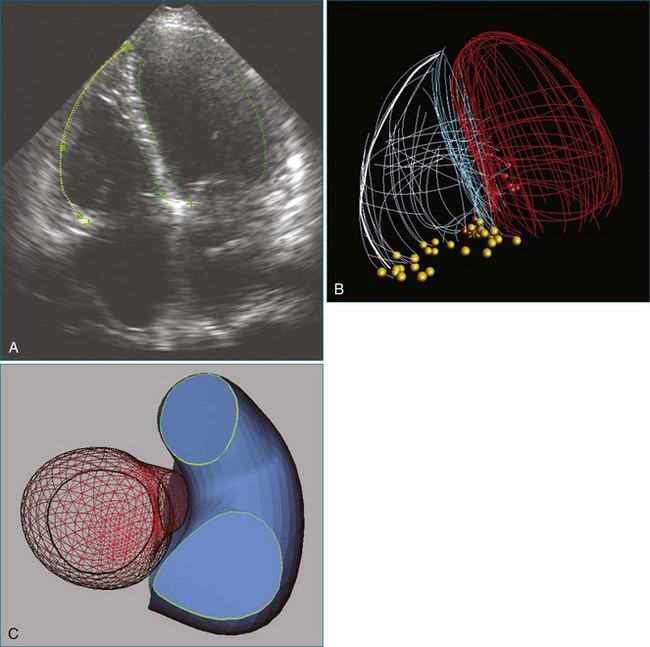

Figure 9-4 (Video 9-4) shows an example of simultaneous visualization of the tricuspid, aortic, and mitral valves.

Figure 9-4 (Video 9-4) shows an example of simultaneous visualization of the tricuspid, aortic, and mitral valves.

Figure 9-5 (Video 9-5) is from a patient with severely elevated pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressure (estimated at 75 mm Hg) by tricuspid regurgitation jet. Recurrent pulmonary emboli were the cause.

Figure 9-5 (Video 9-5) is from a patient with severely elevated pulmonary artery (PA) systolic pressure (estimated at 75 mm Hg) by tricuspid regurgitation jet. Recurrent pulmonary emboli were the cause.

Figure 9-6 (Video 9-6) is from a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, dyspnea, and secondary pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle was severely dilated. PA systolic pressure was estimated at 55 mm Hg. There was severe tricuspid regurgitation from lack of coaptation of the tricuspid valve.

Figure 9-6 (Video 9-6) is from a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus, dyspnea, and secondary pulmonary hypertension. The right ventricle was severely dilated. PA systolic pressure was estimated at 55 mm Hg. There was severe tricuspid regurgitation from lack of coaptation of the tricuspid valve.

Figure 9-7 (Video 9-7) is an RT3D transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) image from a patient with infectious endocarditis and a vegetation on the tricuspid valve. The patient had a history of intravenous drug use, cardiac murmur, chest pain, fever, and elevated white blood cell count.

Figure 9-7 (Video 9-7) is an RT3D transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) image from a patient with infectious endocarditis and a vegetation on the tricuspid valve. The patient had a history of intravenous drug use, cardiac murmur, chest pain, fever, and elevated white blood cell count.

Figure 9-8 (Video 9-8) shows a flail tricuspid valve caused by trauma. The patient had sustained trauma to the chest in a horseback riding accident. There was severe tricuspid regurgitation. The right ventricle was moderately dilated with normal function. RT3DTTE showed the flail leaflet.

Figure 9-8 (Video 9-8) shows a flail tricuspid valve caused by trauma. The patient had sustained trauma to the chest in a horseback riding accident. There was severe tricuspid regurgitation. The right ventricle was moderately dilated with normal function. RT3DTTE showed the flail leaflet.

Figure 9-9 (Video 9-9) shows a patient with severe congestive heart failure and a dilated left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 15%. The right ventricle was moderately dilated. Severe tricuspid regurgitation was caused by the inability of the leaflets to coapt. PA systolic pressure was estimated at 42 mm Hg.

Figure 9-9 (Video 9-9) shows a patient with severe congestive heart failure and a dilated left ventricle with an ejection fraction of 15%. The right ventricle was moderately dilated. Severe tricuspid regurgitation was caused by the inability of the leaflets to coapt. PA systolic pressure was estimated at 42 mm Hg.

Figure 9-10 (Video 9-10) shows a patient with mitral stenosis and secondary pulmonary hypertension. There was moderate to severe right ventricular dilation, with moderately reduced systolic function. Right ventricular systolic pressure by tricuspid regurgitation jet was 51 mm Hg.

Figure 9-10 (Video 9-10) shows a patient with mitral stenosis and secondary pulmonary hypertension. There was moderate to severe right ventricular dilation, with moderately reduced systolic function. Right ventricular systolic pressure by tricuspid regurgitation jet was 51 mm Hg.

Figure 9-11 (Video 9-11) is from a patient with septic shock, normal left and right ventricular function, and a mildly enlarged right ventricle. PA systolic pressure was only moderately elevated at 50 mm Hg. There was prominent pleural effusion, which may have helped obtain the image of the right heart.

Figure 9-11 (Video 9-11) is from a patient with septic shock, normal left and right ventricular function, and a mildly enlarged right ventricle. PA systolic pressure was only moderately elevated at 50 mm Hg. There was prominent pleural effusion, which may have helped obtain the image of the right heart.

Figure 9-12 (Video 9-12) is from a 22-year-old patient referred to the echocardiography laboratory for evaluation of cardiac murmur. Because of very good imaging windows, the en face view of the tricuspid valve was obtained.

Figure 9-12 (Video 9-12) is from a 22-year-old patient referred to the echocardiography laboratory for evaluation of cardiac murmur. Because of very good imaging windows, the en face view of the tricuspid valve was obtained.

Figure 9-13 (Video 9-13) is from a 95-year-old patient referred for echocardiography because of atrial fibrillation. The patient had severe tricuspid regurgitation with hepatic vein reversal. His right ventricle was moderately dilated but did have normal systolic function. Right ventricular systolic pressure was severely elevated and nearly systemic at 90 mm Hg, as estimated by the tricuspid regurgitation jet. Four years after this echocardiogram, the patient was believed to still be alive at age 99 years.

Figure 9-13 (Video 9-13) is from a 95-year-old patient referred for echocardiography because of atrial fibrillation. The patient had severe tricuspid regurgitation with hepatic vein reversal. His right ventricle was moderately dilated but did have normal systolic function. Right ventricular systolic pressure was severely elevated and nearly systemic at 90 mm Hg, as estimated by the tricuspid regurgitation jet. Four years after this echocardiogram, the patient was believed to still be alive at age 99 years.

Figure 9-14 (Video 9-14) shows a patient with severe right ventricular volume and pressure overload. The dilated, hypocontractile right ventricle provides a substrate for optimal image acquisition of the tricuspid valve.

Figure 9-14 (Video 9-14) shows a patient with severe right ventricular volume and pressure overload. The dilated, hypocontractile right ventricle provides a substrate for optimal image acquisition of the tricuspid valve.

Figure 9-15 (Video 9-15) shows images from a 51-year-old patient with severe pulmonary hypertension, systemic-level PA systolic pressure of 100 mm Hg, and chronic pulmonary emboli. The en face imaging of the tricuspid valve is excellent. From the right ventricular side, the individual leaflets can, in this case, be more clearly identified than from the right atrial side.

Figure 9-15 (Video 9-15) shows images from a 51-year-old patient with severe pulmonary hypertension, systemic-level PA systolic pressure of 100 mm Hg, and chronic pulmonary emboli. The en face imaging of the tricuspid valve is excellent. From the right ventricular side, the individual leaflets can, in this case, be more clearly identified than from the right atrial side.

Figure 9-16 (Video 9-16) shows primary pulmonary hypertension that has resulted in severe right ventricular dilation and severe right ventricular dysfunction. The marked right ventricular dilation has allowed particularly clear imaging of the tricuspid valve from the right ventricular side. The anterior leaflet is particularly prominent. The septal leaflet appears to have been stretched by the D-shaped interventricular septum.

Figure 9-16 (Video 9-16) shows primary pulmonary hypertension that has resulted in severe right ventricular dilation and severe right ventricular dysfunction. The marked right ventricular dilation has allowed particularly clear imaging of the tricuspid valve from the right ventricular side. The anterior leaflet is particularly prominent. The septal leaflet appears to have been stretched by the D-shaped interventricular septum.

1 Silver MD, Lam JHC, Ranganathan N, Wigle ED. Morphology of the human tricuspid valve. Circulation. 1971;23:333–348.

2 Raman SV, Sparks EA, Boudoulas H, Wooley CF. Tricuspid valve disease: Tricuspid valve complex perspective. Curr Prob Cardiol. 2002;27(3):103–142.

3 Uijings R, Kluin J, Salomonsz R, et al. Pacemaker lead–induced severe tricuspid valve stenosis. Circ Heart Failure. 2010;3:465–467.

4 Faletra F, La Marchesina U, Bragato R, De Chiara F. Three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography images of tricuspid stenosis. Heart. 2005;91:499.

5 Anwar AM, Geleijnse M. Evaluation of rheumatic tricuspid stenosis using real-time three-dimensional echocardiography. Heart. 2007;93:363.

6 Sultan FAT, Moustafa SE, Tajik J, et al. Rheumatic tricuspid valve disease: An evidence-based systematic overview. J Heart Valve Dis. 2010;19:374.