17 Treatment of the mid-face with botulinum toxin

Summary and Key Features

• The mid-face is an area of complex muscular anatomy, with intimately associated, small muscles

• Proper function of these muscles is essential for accurate emotional conveyance, and particularly smiling. Smile dysfunction can be profoundly disfiguring

• Small starting doses are necessary in the mid-face to obtain desired results and avoid overtreatment, and all precautions should be taken to maximize proper placement and minimize diffusion

• Careful patient selection and full exploration of the risks and benefits of treatment should occur before botulinum toxin injection in this area

Introduction

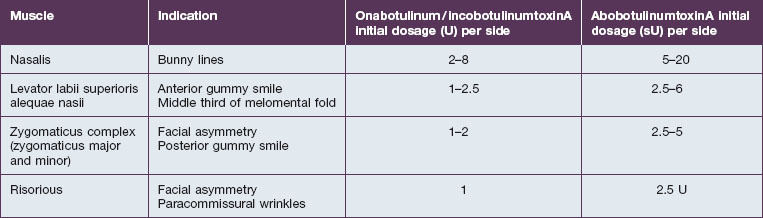

The smaller mid-facial muscles require smaller doses when compared with their upper facial counterparts, especially in initial treatments. The advent of multiple botulinum toxin formulations has added another layer of complexity to this already challenging application and it is important to be aware of proper conversions / dilutions for each toxin (Table 17.1). Small errors in absolute dosage make a large difference in the percentage of the intended doses in this area. The activity of onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox®) and incobotulinumtoxinA (Xeomin®) is measured in murine lethal units (U), with both agents available as 50 U or 100 U per bottle with unit equivalency. It is best to use a higher concentration (e.g. 100 U/mL for Botox®) in the mid- and lower face to minimize toxin diffusion. Abobotulinum toxin A (Dysport®) activity is measured in Speywood units (sU) with either 500 sU or 300 sU/bottle, with a typical dilution of 250 sU/mL. As such, onabotulinum / incobotulinum toxin units and abobotulinum units are not interchangeable, and the exact conversion factor is controversial. According to FDA-approved labeling for the treatment of the glabella, 1 U Botox® is approximately equal to 2.5 sU Dysport®. However, studies have found abobotulinumtoxinA : onabotulinumtoxinA unit ratios to be in the range of 2.5–5 : 1. Some studies such as that by Husseman & Mehta have found abobotulinumtoxinA (Dysport®) to have greater diffusion than onabotulinumtoxinA, meriting even additional caution given the intimately associated nature of the muscles in this area.

‘Bunny’ / nasal sidewall scrunch lines

Injection sites / dosage

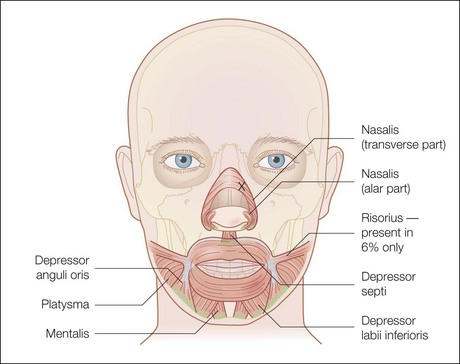

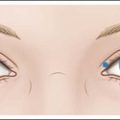

Injection sites for bunny lines are highly individualizable, as are the patterns of the lines. In general, one should ‘inject the fold’ within the following parameters. Injection sites should be kept high on the lateral nasal sidewall (Fig. 17.1) and well medial to the nasofacial sulcus to avoid inadvertent LLSAN weakness. Injections need to be placed only superficially (i.e. intradermally, raising a bleb) to avoid increased diffusion in the low-resistance subnasalis plane. The typical dose ranges have been reported as 2–8 U for onabotulinumtoxinA on each side or 10–20 sU for abobotulinumtoxinA. Figure 17.2 shows a patient before and after bunny line treatment. If LLSAN has a large role in the formation of bunny lines, and the patient is a candidate for LLSAN treatment (as discussed below), that area can be treated concomitantly.

Levator labii superioris alequae nasii

Treatment of this muscle is performed primarily for two desired outcomes. The first is to treat ‘gummy smile’ by lengthening the upper lip in order to reduce the full incisor and upper gum show, as demonstrated in Figure 17.4. Treatment of this muscle can also be used to attenuate the medial nasolabial fold (NLF) in patients whom the etiology is primarily muscular (young patients with a mild to moderate NLF). As for the latter indication, it is important to remember that lip lengthening will occur concomitantly. Most patients in whom dermatoheliosis and soft tissue descent are primarily responsible for the melolabial fold, and in whom a ‘gummy smile’ is absent, will be better served by filler injection for treatment of the melolabial fold.

Injection sites / dosage

The LLSAN should be injected at the pyriform aperture / apical triangle of the upper lip, 1 cm above the lateral extent of the ala (Fig. 17.3); inject 1–2.5 U onabotulinum toxin per side in the supraperiosteal plane. The effect can be long lasting (~ 6 months) making rigorous patient selection and injection technique paramount. Figure 17.4 shows a patient before and after botulinum toxin injection to the LLSAN.

Zygomaticus complex

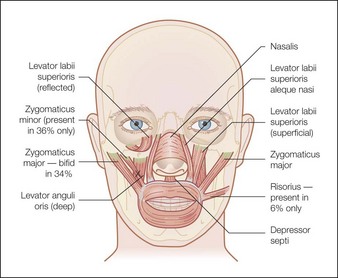

The zygomaticus complex is composed of the zygomaticus major and minor muscles (Fig. 17.5). The zygomaticus major originates laterally on the zygomatic arch deep to the orbicularis oculi muscle and inserts in the modiolus. It therefore pulls the lateral oral commissure superolaterally and dilates the oral aperture. Symmetrical movement of this muscle is perceived as smiling, whereas unilateral movement can give an impression of ‘sneering’. Additionally, dermal connection of this muscle through the SMAS may contribute to dimple formation.

Risorius

Injection sites / dosage

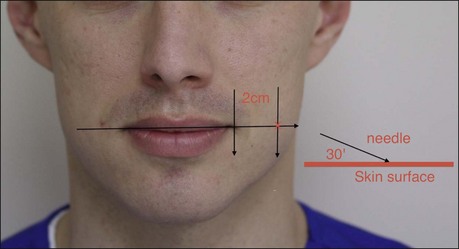

The risorious injection site should be identified by drawing a horizontal line through the oral commissure. Move laterally along this line away from the oral commissure for 2 cm. From this point enter the skin at a 30° angle with the needle pointed laterally, away from the oral commissure (Fig. 17.6). The typical risorius dosage is 1 U onabotulinumtoxinA.

Ascher B, Talarico S, Cassuto D, et al. International consensus recommendations on the aesthetic usage of botulinum toxin type A (Speywood unit) – Part II: wrinkles on the middle and lower face, neck and chest. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 2010;24(11):1285–1295.

Basting RT, da Trindade R de C, Flório FM. Comparative study of smile analysis by subjective and computerized methods. Operative Dentistry. 2006;31(6):652–659.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Botulinum toxin A in the mid and lower face and neck. Dermatologic Clinics. 2004;22:151–158.

Carruthers JD, Glogau RG, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type A, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121:S5–S30.

Husseman J, Mehta RP. Management of synkenesis. Facial Plastic Surgery. 2008;24(2):242–249.

Mazzuco R, Hexsel D. Gummy smile and botulinum toxin: a new approach based on the gingival exposure area. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010;63(6):1042–1051.

Raspaldo H, Baspeyras M, Bellity P, et al. Consensus Group. Upper- and mid-face anti-aging treatment and prevention using onabotulinumtoxin A: the 2010 multidisciplinary French consensus – part 1. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2011;10(1):36–50.

Raspaldo H, Baspeyras M, Bellity P, et al. Consensus Group. Lower-face and neck antiaging treatment and prevention using onabotulinumtoxin A: the 2010 multidisciplinary French consensus – part 2. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2011;10(2):131–149.

Sattler G, Callander MJ, Grablowitz D, et al. Noninferiority of incobotulinumtoxinA, free from complexing proteins, compared with another botulinum toxin type A in the treatment of glabellar frown lines. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36(suppl 4):2146–2154.

Spiegel JH, Derosa J. The anatomical relationship between the orbicularis oculi muscle and the levator labii superioris and zygomaticus muscle complexes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2005;116(7):1937–1942.

Toffola ED, Furini F, Redaelli C, et al. Evaluation and treatment of synkinesis with botulinum toxin following facial nerve palsy. Disability Rehabilitation. 2010;32(17):1414–1418.

Trindade de Almeida AR, Marques E, et al. Pilot study comparing the diffusion of two formulations of botulinum toxin type A in patients with forehead hyperhidrosis. Dermatologic Surgery. 2007;33(1):S37–S43.