14

Treatment of the complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and failed gastro-oesophageal surgery

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux affects up to a quarter of the UK population on a regular basis. Most will not seek medical help and self-medicate. Of those who do see a doctor the vast majority will be well controlled by medical therapy – invariably proton-pump inhibitors. It has been calculated that only 1% of patients with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) will develop complications of the reflux. These complications are consequent on damage to the mucosa resulting in erosive oesophagitis with, rarely, a peptic oesophageal ulcer, a peptic stricture or Barrett’s oesophagus (see Chapter 15). The vast majority of sufferers of GORD have non-erosive reflux disease (NERD) and never develop either erosive oesophagitis or Barrett’s oesophagus.1

There are two main treatments for GORD. These are medical therapy with proton-pump inhibitors or surgical therapy based on either a total or partial fundoplication. Comparative studies suggest there is little to choose between the two therapeutic arms in either the control of symptoms or prevention of complications. This is well documented in the results of the multicentre LOTUS trial, comparing esomeprazole and laparoscopic antireflux surgery, with good control of symptoms and microscopic oesophagitis in over 85% of cases in both arms out to 5 years.2,3

In recent years there has been a significant increase in the use of fundoplication based on the laparoscopic approach. This is claimed to be a one-off long-term treatment that removes the need for expensive long-term ingestion of proton-pump inhibitors. However, it is recognised that with time the use of these drugs does increase in patients who have had a successful initial surgical outcome, reaching 25% at 10 years.4,5

In the USA, the number of antireflux operations increased by 260% between 1993 and 2000 but decreased by 40% between 2000 and 2006.6 Similar trends have been seen in Europe, particularly in Sweden. The reasons are unclear but may reflect disappointing long-term results for surgery, with a significant proportion of patients back on medical therapy as described above and recognition of the complications, which although rare can have a serious impact on a young, previously fit patient.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux results from failure of the lower oesophageal sphincter to either provide a mechanical barrier (volume/supine refluxers) or which relaxes inappropriately, usually secondary to gaseous distension of the gastric fundus (upright refluxers). These differences can have an effect on the outcome of antireflux surgery whereas defective oesophageal motility, other than undiagnosed achalasia, does not.7,8

Complications of GORD

Complications arise from damage caused by the refluxate to the squamous mucosa of the oesophagus. The contents of the refluxate may include any combination of acid and/or ‘bile’ (duodenogastric contents). Chronic exposure of the oesophageal mucosa to this fluid in patients with an intact stomach causes inflammation, can result in erosive oesophagitis with ulceration and subsequent peptic stricture, and in some results in metaplastic change and the development of Barrett’s oesophagus. It appears that acid alone is the principal factor in determining the severity of oesophagitis, whereas in patients experiencing symptoms who are on long-term proton-pump inhibitors weak acid or bile is implicated.9,10

Short oesophagus

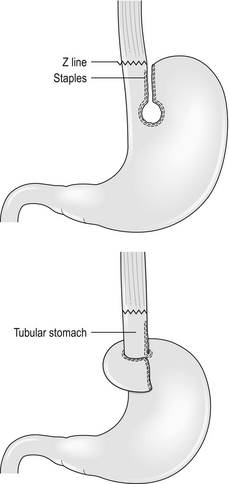

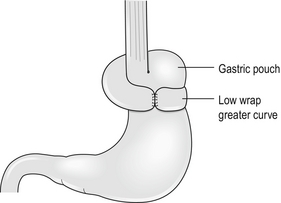

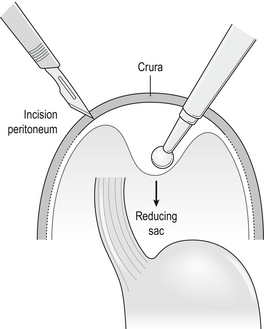

Those who recognise the complication advocate a Collis gastroplasty to lengthen the oesophagus through either an open abdominal or laparoscopic approach. It may provide a better outcome in such patients when compared with fundoplication alone.11 In this procedure a 40 F bougie is passed into the stomach and kept on the lesser curve. A neo-oesophagus is created using a circular and linear cutting stapler and a loose wrap performed using the mobilised stomach (Fig. 14.1). This has the potential to leave a tube of acid-secreting stomach above the wrap, with consequent complications of bleeding, ulceration and stenosis. It has been used in revisional surgery, where mobilisation of the gastro-oesophageal junction below the diaphragm has proven difficult. In experienced hands the results are reported to be good.12

Gastrointestinal haemorrhage

The treatment of erosive oesophagitis is medical with proton-pump inhibitors in the first instance, with excellent healing rates, although double-dose treatment may be required with maintenance therapy after healing has been achieved.13 To attribute gastrointestinal haemorrhage to erosive oesophagitis is a matter of exclusion after full endoscopic examination as it is not a common cause of significant bleeding except in those with a tendency to bleeding, usually as a result of other medication they are taking.

Peptic oesophageal stricture

The incidence of symptomatic stricture is extremely low in the pantheon of reflux disease. The management involves endoscopy and biopsy to exclude serious pathology followed by optimum acid inhibition with proton-pump inhibitors and H2-receptor antagonists and gentle dilatation with an endoscopic balloon (Fig. 14.2). The diameter is dependent on the size of the stricture but it is better to undertake sequential dilatation starting with a 10-mm balloon rather than use too big a balloon and risk splitting the oesophagus. The risk of perforation is of the order of 2–3%. This should be recognised at the time and treated conservatively with nil by mouth, intravenous proton-pump inhibitors and antibiotics plus placement of a nasojejunal tube under screening for feeding. Success can be achieved in over 90% of cases with conservative management. If the perforation is not recognised and the patient develops sepsis then a more aggressive approach is required, including drainage and surgical repair. Such patients are best referred to specialist centres with full intensive care and interventional radiological support.14,15 The use of self-expanding plastic stents in such perforations shows promise but can cause problems and is best avoided. Any stent used in this context must be removable.

Patients with symptomatic peptic strictures will often require repeat dilatation to maintain swallowing. In such cases injection of steroids can be beneficial and division of a tight band-type stricture with a laser can reduce the frequency of dilatation.16 The use of self-expanding plastic stents is controversial and in resistant strictures only removable stents (plastic) or the new biodegradable stents should be used.17 The patient with a stricture resistant to these treatments may require surgical resection. Such cases may be technically difficult as there has been transmural inflammation or perforation and an open approach is recommended. An algorithm is shown in Box 14.1.

Failed antireflux surgery

Failure may be due to persistence or recurrence of reflux symptoms, development of new symptoms or complications of the surgical procedure. The incidence of complications17–19 is listed in Table 14.1. Complications and failures tend to occur soon after laparoscopic surgery and later after open surgery.

Table 14.1

Complications of antireflux surgery

| Pneumothorax | 2% | |

| Paraoesophageal hernia | 7% | |

| Dysphagia – Slipped wrap, tight wrap, tight hiatus | early late |

34% 6% |

| Perforated oesophagus | 1% | |

| Bloating/diarrhoea | 30% |

As described above, the success rate for fundoplication in controlling symptoms is in the region of 85% using accepted criteria for surgical success – volume reflux, failed medical treatment, etc.2–5 This implies that 15% fail and with time even successful initial surgery results in 25% of patients subsequently requiring regular medication.

It is now recognised that the type of wrap (partial or total) does not have a long-term effect on dysphagia, although total fundoplication may give better control of reflux symptoms whereas partial fundoplication has less dysphagia in the short term, although this difference disappears with time.20,21

Investigation of the failed antireflux operation

Barium studies

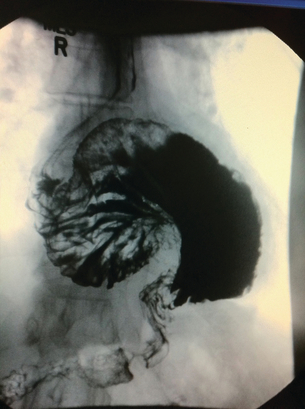

Barium studies provide important information about both anatomy and function. A swallow can demonstrate the pattern of obstruction and its relation to the diaphragm. It can also demonstrate the integrity of a wrap and slippage into the chest (Figs 14.3 and 14.4), which is not infrequently associated with volvulus (Fig. 14.5). It is also important to look at the gastric component of the study to visualise gastric emptying and pyloric function.

Computerised tomography

CT scanning with contrast should be undertaken in all cases where malignancy is suspected with endoluminal ultrasound scan if there is doubt. It is also invaluable where there is a large intrathoracic stomach to display the anatomy, especially if the repair is to be undertaken using the transabdominal approach (Fig. 14.6). CT is almost invariably contributory in difficult revisional cases.

Oesophageal physiology tests

Repeat oesophageal physiology and in particular oesophageal impedance can be very revealing in failed surgery, especially if it was not undertaken prior to original surgery. The missed diagnosis of achalasia will invariably result in dysphagia, as will scleroderma where the oesophagus is amotile. There is no evidence, however, that normal but low-amplitude motility affects outcome, and high-amplitude waves may be associated with a tight wrap.8

The results of 24-hour pH monitoring post-fundoplication are very interesting.22 The usual pattern is that there is no measurable reflux in spite of symptoms that seem classical of reflux. This relates to the observation that many patients undergoing revisional surgery for recurrent symptoms have a wrap that is in good position and is intact. The cause of the symptoms is therefore unclear and caution must be expressed on the successful outcome of re-operation. When the pH studies are positive and there is good symptom correlation and positive DeMeester score, this will usually be associated with wrap disruption and a better outcome can be expected with revision.

Management of failure after antireflux surgery

Recurrence of reflux symptoms

Recurrence of symptoms as described earlier is more common than generally recognised and a significant proportion of patients (25%) are back on medication post-surgery, although their symptoms are better controlled. It is wise to repeat the physiology studies in such patients to identify those who have true reflux, especially if considering revisional surgery.23

The reasons for this recurrence of symptoms include wrap disruption, wrap slippage and migration into the chest. The latter is more frequent when at the first operation there was a large hiatal defect, which was not closed properly with sutures, and if the sac was not excised from the chest or the repair was associated with tension (Fig. 14.7). Closure of a large hiatus with removal of the sac can be difficult, especially when undertaken laparoscopically, and if problems arise this should lead to conversion to open surgery. An alternative is to close the hiatus with a mesh, preferably from behind the oesophagus. Good results have been reported using this technique but caution is needed as the mesh can erode the oesophagus and cause dense strictures at the hiatus.23,24 Removal will invariably require open surgery, usually via a thoracoabdominal incision with an oesophagogastrectomy. The use of man-made products to cover the hiatus adjacent to the oesophagus should be avoided if at all possible.

Failure of the symptoms to improve after surgery questions the original diagnosis and may be associated with a sensitive oesophagus. It can be related to a ‘bad’ operation when the wrong part of the stomach is brought up (Fig. 14.8). This can produce the equivalent of a gastric band as used in bariatric surgery. Such patients often experience significant weight loss in the postoperative period and require revisional surgery.

Persistence of preoperative symptoms

Persistence of symptoms suggests that the original diagnosis was at fault. Review of preoperative 24-hour pH and oesophageal manometry together with a repeat study may reveal underlying motility disorders such as achalasia, lack of symptom correlation and low DeMeester scores. Such patients tend to be upright refluxers or if the original studies were negative may represent ‘functional heartburn’.25 Taking down the wrap in the absence of dysphagia is unlikely to benefit the patient and is only a last resort. Other causes of pain must be sought and 24-hour pH study on and off full-dose medical treatment can be revealing.

Dysphagia

Dysphagia persisting beyond 2 months may be due to a pre-existing motility disorder, an over-tight wrap, scarring in the hiatus or over-tight repair of the hiatus. If in doubt, especially in cases where fluids only can be taken, early barium studies can be very helpful,26 revealing migrated or slipped wraps or strictures at the hiatus (Figs 14.3 and 14.4). If the stenosis is thought to be due to stricturing of the hiatus then care should be taken with dilatation as the oesophageal wall can be compressed against a hard fibrous band and the result is invariably poor (Fig. 14.9). The solution to this is re-operation and incision of the fibrous hiatal ring to release the oesophagus. It is important to visualise and avoid injury to the inferior phrenic vein when undertaking this procedure. This procedure can be achieved laparoscopically in most cases.

Figure 14.9 Balloon dilatation of a tight hiatal ring demonstrating the resistant short stricture characteristic of this complication.

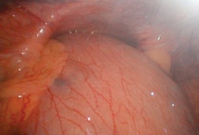

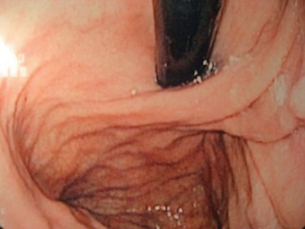

When dysphagia arises after a period of normal swallowing this may be due to wrap slippage or migration but may indicate the development of malignancy, especially if the operation was performed for Barrett’s oesophagus. The first investigation is endoscopy (Fig. 14.10), biopsy of any suspicious lesion and balloon dilatation of the wrap up to 20 mm with an endoscopic balloon dilatator. Barium studies and CT are also indicated as wrap migration into the chest may not be obvious on endoscopy (Fig. 14.11).

The incidence of dysphagia is initially less when a partial wrap is performed, in contrast to a full 360° Nissen fundoplication. The use of a partial fundoplication is increasing, with no apparent reduction in efficacy in the control of reflux.20,21 Certainly, in patients with pre-existing motility disorders such as scleroderma, or as part of surgery for achalasia, a partial wrap should be undertaken or dysphagia is likely.

Revisional surgery following failed antireflux surgery

Care should be taken in recommending re-operation in patients with persistent or recurrent symptoms in whom the investigations reveal an intact wrap in a good position and normal physiological studies. However, if re-operation is undertaken for the correct reasons then the outcome is generally good, although the outcome is worse if re-operation is for dysphagia.12,27

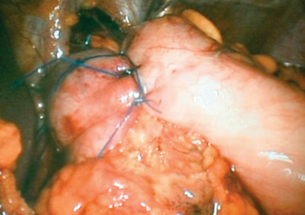

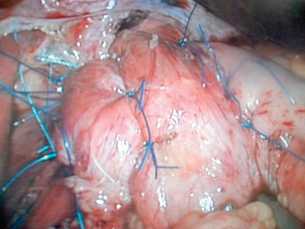

This should not be undertaken by an occasional surgeon or by one who is unfamiliar with entering the chest. The most frequently used procedure is revision of the fundoplication, either redoing a 360° wrap or converting it to a partial wrap, together with appropriate hiatal repair (Figs 14.12 and 14.13). This can be undertaken laparoscopically, especially if the previous procedure was laparoscopic, but should be converted to open surgery if any difficulty is encountered.

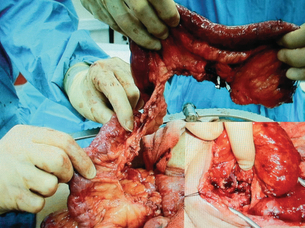

This approach makes reduction of a stomach that has slipped into the chest easier. The sac can be reduced by blunt dissection from the front of the hiatus, dividing the peritoneum with a diathermy point and extending this to the right and left, thus exposing the crura. The sac should be fully excised (Fig 14.14).

Posterior repair of the hiatus can be achieved by placing non-absorbable sutures in the left crus and bringing them behind the oesophagus to place in the right crus. Usually, three well-placed sutures are enough to close the hiatus without tension. This invariably enables avoidance of the use of mesh. Full mobilisation of the fundus and short gastric vessels enables a loose 360° or 270° wrap to be performed. On completion of the wrap, it is sutured to the right crus with two or three non-absorbable sutures (Fig. 14.13).

It is reasonable to have one attempt at repairing and revising a wrap. Further operations may well result in a devitalised gastro-oesophageal zone necessitating oesophagogastric resection via a left thoracoabdominal approach with a 25-mm stapled anastomosis at the aortic arch.28 The gastric tube is based on the right gastroepiploic artery and should be no more than 3 cm wide. Unless there is previous peptic ulceration, a pyloroplasty is not needed and the addition of a wrap at the anastomosis does not protect from reflux. If the stomach is not suitable then a short-segment colonic interposition is an alternative approach. The functional result of such a procedure will never be ‘normal’.

Complex revisional surgery

Oesophageal occlusion usually results from ingestion of caustic fluids with either complete occlusion of the oesophagus from the pharynx or a long tight complex stricture.29 Rare causes include epidermolysis bullosa.30 In such cases the pharynx is also involved with inflammation and fibrosis and patients are unable to swallow their own saliva and have permanent gastrostomy feeding. A colonic interposition between the pharynx and stomach or a jejunal loop can in many cases restore swallowing, although pharyngeal fibrosis inhibits the initiation of swallowing. If the stricture is high with a relatively normal oesophagus below, then a pharyngoplasty can help.

It is now recognised that in cases of failed oesophageal resection with tube necrosis of major anastomotic breakdown, resection of the conduit with cervical oesophagostomy and stapling off the distal end can be life saving. Similar oesophageal resection or exclusion can have benefits in Boerhaave’s syndrome with oesophageal necrosis and mediastinitis.31 Such patients require reconstruction to restore continuity when they have recovered. This can usually be achieved by the use of either a colonic interposition or a long ‘supercharged’ jejunal Roux-en-Y loop.32,33

In cases where the colon is unavailable, a supercharged jejunal loop can be used. In order to reach the neck, the proximal part of the loop will be ischaemic and requires ‘supercharging’ by a microvascular anastomosis between a mesenteric artery and usually the left internal mammary artery and a venous anastomosis to any suitable vein (Figs 14.15 and 14.16).

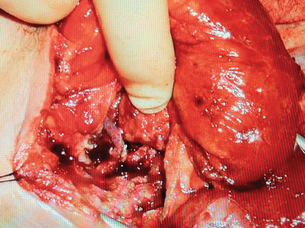

Figure 14.15 A long supercharged Roux loop showing the long mesentery and dusky appearance at the top end.

Figure 14.16 The same loop following microvascular anastomosis in the neck and the well-vascularised bowel.

There are now an increasing number of patients in their thirties who had successful surgery for oesophageal atresia in infancy. This was invariably a colonic interposition via the left chest with multiple neck and thoracic operations. In such cases presenting with difficulty in swallowing, it is crucial to investigate thoroughly prior to considering any reconstruction to determine accurately the site of obstruction. This can be at the root of the neck, which bulges on swallowing, in redundant colonic loops in the chest, or at the level of the diaphragm where a fibrotic stricture causes a mechanical obstruction and proximal dilatation. Investigation includes endoscopy, barium studies and contrast-enhanced CT scanning (Fig. 14.17).

The most common causes for difficulty in swallowing are redundant colonic loops and strictures at the diaphragm.33,34,35 A long left thoracoabdominal approach gives the best access, and it is crucial to identify the vascular pedicle at an early stage and preserve it at all costs. The diaphragm is split to the hiatus, the cologastric anastomosis taken down, redundant colon excised with a harmonic scalpel keeping to the bowel wall, preserving the vascular arcade and re-anastomosis of the colon to stomach. The diaphragm is closed without any compression at the new pseudo-hiatus. Such patients will require jejunostomy feeding for some time.

References

1. Fass, R., Ofman, J.J., Gastroesophageal reflux disease – should we adopt a new conceptual framework? Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97:1901–1909. 12190152

2. Fiocca, R., Mastracci, L., Engstrom, C., et al, Long-term outcome of microscopic esophagitis in chronic GERD patients treated with esomeprazole or laparoscopic antireflux surgery in the LOTUS trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2010; 105:1015–1023. 19904246

3. Galmiche, J.P., Hatlebakk, J., Attwood, S., et al, Laparoscopic antireflux surgery vs esomeprazole treatment for chronic GERD: the LOTUS randomised clinical trial. JAMA 2011; 305:1969–1977. 21586712 A randomised study demonstrating the equal efficacy of medical and surgical treatment of GORD.

4. Broeders, J.A., Rijnhart-de Jong, H.J., Draaisma, W.A., et al, Ten-year outcome of laparoscopic and conventional Nissen fundoplication. Ann Surg 2009; 250:698–706. 19801931

5. Kelly, J.J., Watson, D.I., Chin, K.F., et al, Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication: clinical outcomes at 10 years. J Am Coll Surg 2007; 205:570–575. 17903731

6. Wang, Y.R., Dempsey, D.T., Richter, J.E., Trends and perioperative outcomes of inpatient antireflux surgery in the United States 1993–2006. Dis Esophagus 2011; 24:215–223. 21073616

7. Zingg, U., Smith, L., Carney, N., et al, The influence on outcome of indications for antireflux surgery. World J Surg 2010; 34:2813–2820. 20706837

8. Broeders, J.A., Sportel, I.G., Jamieson, G.G., et al, Impact of ineffective motility and wrap type on dysphagia after laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg 2011; 98:1414–1421. 21647868

9. Richter, J.E., Role of the gastric refluxate in gastroesophageal reflux disease: acid, weak acid and bile. Am J Med Sci 2009; 338:89–95. 19590427

10. Brillantins, A., Monaco, L., Schettmo, M., et al, Prevalence of pathological duodenogastric reflux and the relationship between duodenogastric and duodenogastroesophageal reflux in chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 20:1136–1143. 18946360

11. Nason, K.S., Luketich, J.D., Awais, O., et al, Quality of life after Collis gastroplasty for short esophagus in patients with paraesophageal hernia. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92:1854–1861. 21944737

12. Awais, O., Luketich, J.D., Schuchert, M.J., et al, Reoperative antireflux surgery for failed fundoplication: an analysis of outcomes in 275 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 92:1083–1089. 21802068 An extensive experience of revisional surgery with good outcomes. Good guidance for those undertaking these procedures.

13. Edwards, S.J., Lind, T., Lundell, L., et al, Systematic review: standard- and double-dose proton pump inhibitors for the healing of severe erosive oesophagitis – a mixed treatment comparison of randomized controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2009; 30:547–556. 19558609

14. Kuppasamy, H.K., Hubka, M., Felisky, C.D., et al, Evolving management strategies in oesophageal perforation: surgeons using non-operative techniques to improve outcome. J Am Coll Surg 2011; 213:164–171. 21429768

15. Søreide, J.A., Viste, A., Esophageal perforation: diagnostic workup and clinical decision making in the first 24 hours. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011; 19:66. 22035338 An excellent overview of the problem of perforation with guidance for management.

16. De Wijkerslooth, L.R., Vleggaar, F.P., Siersema, P.D., Endoscopic management of difficult or recurrent esophageal strictures. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:2080–2091. 22008891 This gives an excellent overview of the management of recalcitrant oesophageal strictures with a management plan that is evidence based.

17. Repici, A., Vieggaar, F.P., Hassan, C., et al, Efficacy and safety of biodegradable stents for refractory benign oesophageal strictures. The BEST study. Gastrointest Endosc 2010; 72:927–934. 21034894

18. Watson, D.I., de Beaux, A.C., Complications of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Surg Endosc 2001; 15:344–352. 11395813

19. Richter, J.E., Let the patient beware: the evolving truth about laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Am J Med 2003; 114:71–73. 12543294 A cautionary note before recommending surgery. Should be part of preoperative consent.

20. Nijjar, R.S., Watson, D.I., Jamieson, G.G., et al, Five year followup of a multicentre, double blinded randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen vs anterior 90 degree partial fundoplication. Arch Surg 2010; 145:552–557. 20566975

21. Mardani, J., Lundell, L., Engstrom, C., Total or posterior partial fundoplication in the treatment of GERD: results of a randomised trial after 2 decades of followup. Ann Surg 2011; 253:875–878. 21451393 Demonstrates that the type of fundoplication does not matter.

22. Thompson, S.K., Jamieson, G.G., Myers, J.C., et al, Recurrent heartburn after laparoscopic fundoplication is not always recurrent reflux. J Gastrointest Surg 2007; 11:642–647. 17468924

23. Antoniou, S.A., Koch, O.O., Antoniou, G.A., et al, Mesh reinforced hiatal hernia repair: a review on the effect on postoperative dysphagia and recurrence. Langenbecks Arch Surg 2012; 397:19–27. 21792699

24. Soricelli, E., Basso, N., Genco, A., et al, Long term results of hiatal hernia mesh repair and antireflux laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc 2009; 23:2499–2504. 19343437

25. Thompson, S.K., Cai, W., Jamieson, G.G., et al, Recurrent symptoms after fundoplication with a negative pH study – recurrent reflux or functional heartburn? J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13:54–60. 18712573

26. Tsunoda, S., Jamieson, G.G., Devitt, P.G., et al, Early reoperation after laparoscopic fundoplication: the importance of routine postoperative contrast studies. World J Surg 2010; 34:79–84. 19777296

27. Lamb, P.J., Myers, J.C., Jamieson, G.G., et al, Longterm outcomes of revisional surgery following laparoscopic fundoplication. Br J Surg 2009; 96:391–397. 19283739 Demonstrates that revisional surgery can be beneficial if done for the correct reasons.

28. Forshaw, M.J., Gossage, J.A., Ockrim, J., et al, Left thoracoabdominal oesophagogastrectomy: still a valid operation for carcinoma of the distal oesophagus and oesophagogastric junction. Dis Esophagus 2006; 19:340–345. 16984529

29. Ananthakrishnan, N., Kate, V., Parthasarathy, G., Therapeutic options for management of pharyngooesophageal corrosive strictures. J Gastrointest Surg 2011; 15:566–575. 21331658 Demonstrates the problems with corrosive strictures from an area of high prevalence, which unfortunately is becoming more common in the UK.

30. Elton, C., Marshall, R.E., Hibbert, J., et al, Pharyngogastric colonic interposition for total oesophageal occlusion in epidermolysis bullosa. Dis Esophagus 2000; 13:175–177. 14601913

31. Barkley, C., Orringer, M.B., Iannettoni, M.D., et al, Challenges in reversing esophageal discontinuity operations. Ann Thorac Surg 2003; 76:989–994. 14529973 An extensive experience of an uncommon and varied problem. Should be read by anyone wanting to undertake such operations.

32. Dowson, H.M., Strauss, D., Ng, R., et al, The acute management and surgical reconstruction following failed esophagectomy in malignant disease of the esophagus. Dis Esophagus 2007; 20:135–140. 17439597

33. Khan, A.Z., Nikolopous, I., Botha, A.J., et al, Substernal long segment left colon interposition for oesophageal replacement. Surgeon 2008; 6:54–56. 18318090

34. Strauss, D.C., Forshaw, M.J., Tandon, R.C., et al, Surgical management of colonic redundancy following esophageal replacement. Dis Esophagus 2008; 21:E1–E5. 18430095

35. Dhir, R., Sutcliffe, R.P., Rohatgi, A., et al, Surgical management of late complications after colonic interposition for esophageal atresia. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86:1965–1967. 19022019