4 Treatment of mania

4.1 What is the best treatment for mania?

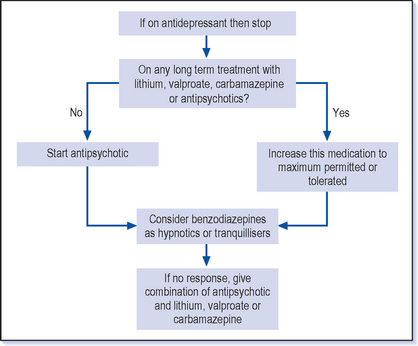

![]() The first step in the treatment of mania is to stop the antidepressants. There are then two main lines of treatment in acute manic relapses. The first is to increase the long-term treatment–for example if the patient is already taking lithium then the levels should be checked and, providing it is being tolerated reasonably well, to increase the dose, aiming for a level of up to 1.0 mmol/l (occasionally up to 1.2 mmol/l). A similar approach can be adopted with valproate and carbamazepine. The alternative line is to give a specific antimanic treatment, usually an antipsychotic, either on its own or in combination with a long-term treatment (Fig. 4.1).

The first step in the treatment of mania is to stop the antidepressants. There are then two main lines of treatment in acute manic relapses. The first is to increase the long-term treatment–for example if the patient is already taking lithium then the levels should be checked and, providing it is being tolerated reasonably well, to increase the dose, aiming for a level of up to 1.0 mmol/l (occasionally up to 1.2 mmol/l). A similar approach can be adopted with valproate and carbamazepine. The alternative line is to give a specific antimanic treatment, usually an antipsychotic, either on its own or in combination with a long-term treatment (Fig. 4.1).

4.2 How are antipsychotics used in mania?

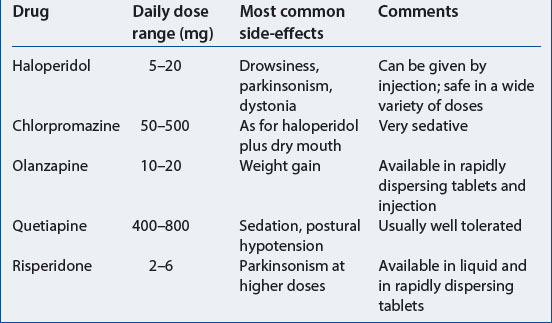

Olanzapine, quetiapine and risperidone are the atypical antipsychotics that are licensed for the treatment of mania but it is probably true that all antipsychotic drugs, including the newest one, aripiprazole, improve manic symptoms. These drugs are relatively free of parkinsonian side-effects, and are generally well tolerated (Table 4.1). They are available in either rapidly dispersing tablets or liquid which can be helpful when compliance is in doubt. Olanzapine is now also available as an injection.

4.4 What other treatments are effective in mania apart from antipsychotics?

VALPROATE

Valproate is the main alternative acute treatment and has the advantage of being effective, well tolerated and easy to use. Depakote is the formulation that is licensed for the treatment of mania as the studies have been done using this form (Bowden et al 2000, NICE Technology Appraisal 66). This particular formulation provides higher blood levels for the same apparent dose compared to other forms of valproate. The usual starting dose is 750 mg daily (250 mg tablets spread over two doses). It can then be increased gradually over a week up to 1500 mg or further to 2 g if necessary. It would seem likely that the other forms of valproate are also effective but licensed preparations are generally preferred (see National Institute for Clinical Excellence guidelines, www.nice.org.uk).

LITHIUM

Lithium is also an effective antimanic treatment and is used in similar doses and with similar blood levels to those used in preventive treatment (see Chapter 5). Higher doses with levels up to 1.0 mmol/l or even slightly higher than this are sometimes used. There are several difficulties in using lithium in mania:

Patients who are severely ill may be drinking little and are therefore liable to dehydration; this makes treatment with lithium more difficult and potentially dangerous.

Patients who are severely ill may be drinking little and are therefore liable to dehydration; this makes treatment with lithium more difficult and potentially dangerous. It is difficult to find the effective dose rapidly as increases are usually done gradually: it can take a couple of weeks to reach a therapeutic dose and manic symptoms often need more urgent treatment than this.

It is difficult to find the effective dose rapidly as increases are usually done gradually: it can take a couple of weeks to reach a therapeutic dose and manic symptoms often need more urgent treatment than this. Another reason relates to starting a long-term preventive treatment when a patient is manic and is not capable of making longer term decisions. Stopping lithium suddenly can cause a rebound manic effect (see Chapter 5). If lithium is started when patients are acutely manic and not committed to long-term treatment, they are likely to stop when they have recovered and this will risk precipitating a further episode of mania. This effect is not so apparent with antipsychotics and valproate.

Another reason relates to starting a long-term preventive treatment when a patient is manic and is not capable of making longer term decisions. Stopping lithium suddenly can cause a rebound manic effect (see Chapter 5). If lithium is started when patients are acutely manic and not committed to long-term treatment, they are likely to stop when they have recovered and this will risk precipitating a further episode of mania. This effect is not so apparent with antipsychotics and valproate.BENZODIAZEPINES

Benzodiazepines are also commonly used in mania. They are used generally for their sedative effect and particularly in cases where urgent calming and sleep induction are necessary. Lorazepam (0.5-1 mg) as an intramuscular injection is an effective emergency treatment for acute psychosis including mania (see Q 4.9). In the early days of treating excited manic patients many doctors give diazepam which has a long half-life, helps to improve sleep and has a calming effect during the day. Clonazepam is also used and there have been some studies to show this is effective in mania on its own, though it is unusual to treat mania only with benzodiazepines.

4.5 What if the mania is not improving on antimanic treatment?

This is a similar answer to that of treating depression that does not improve (see Q 3.9). The following questions should be considered before contemplating a change in medication:

Have you given the treatment long enough?: For example, at least 4 weeks with no or only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement, but if the treatment is changed too early the benefits of the medication may be missed.

Have you given the treatment long enough?: For example, at least 4 weeks with no or only minor response. It can be difficult to stick with the treatment when there is little improvement, but if the treatment is changed too early the benefits of the medication may be missed. Have you tried a higher dose?: If the patient is not getting better, doses should be increased to the maximum dose that is recommended, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antimanic.

Have you tried a higher dose?: If the patient is not getting better, doses should be increased to the maximum dose that is recommended, provided that the treatment is reasonably tolerated before turning to an alternative antimanic. Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: This is usually a problem in the treatment of mania as most patients have limited insight into their condition and so are unlikely to be taking the treatment correctly. There is also a fair chance that they are deliberately concealing their non-compliance rather than refusing. It is not uncommon to find a stack of tablets hidden away in a patient’s room when they have appeared entirely willing to take the treatment (see also Q 5.43). Can you arrange some supervision of the treatment and give it in a formulation that is harder to evade–a liquid or dispersible tablet?

Have you assessed concordance/compliance?: This is usually a problem in the treatment of mania as most patients have limited insight into their condition and so are unlikely to be taking the treatment correctly. There is also a fair chance that they are deliberately concealing their non-compliance rather than refusing. It is not uncommon to find a stack of tablets hidden away in a patient’s room when they have appeared entirely willing to take the treatment (see also Q 5.43). Can you arrange some supervision of the treatment and give it in a formulation that is harder to evade–a liquid or dispersible tablet?4.6 What are the next lines of treatment in mania that has not responded to the first antimanic treatment?

There are other options available but these would usually be restricted to specialist use. These include carbamazepine, lamotrigine (see Q 3.4), benzodiazepines (including clonazepam) or ECT (see Q 3.22).

4.8 How are psychotic symptoms in mania treated?

The antimanic treatments outlined above should lead to an improvement of psychotic symptoms as the other symptoms of mania abate. It is not essential to use antipsychotic medications when psychotic symptoms are present if other treatments (e.g. lithium or valproate) are being used. This differs from the advice in psychotic depression where antipsychotic drugs are always recommended. On the other hand mania without psychotic symptoms can be (and usually is) treated with antipsychotic drugs.

4.10 Do antipsychotics increase the risk of switching into depression?

It is common for depression at some level to follow mania and about a third of patients can expect this. This may be in part an understandable reaction when the reality of the fallout from the manic behaviour is starting to impact. It is possible that antipsychotics exacerbate this tendency but if the patient is taking lithium then this medicine may help to prevent the depressive swing. Atypical antipsychotics may be less likely to precipitate depression.

4.12 Is ECT an effective treatment for mania?

Electroconvulsive therapy can be a useful treatment in mania though it is rarely used. It is reserved for those whose mania has become life-threatening because of nutritional or hydration problems and usually when other treatments are also being tried. The author has given it only once in the last 10 years and that was to a patient who had become almost impossible to communicate with and who wouldn’t eat or drink although she gave no clear reason why not. The situation in which it is more commonly used is in the treatment of puerperal psychosis (see Q 6.18).

4.13 What investigations are needed?

![]() The most important investigation is monitoring the physical state of the patient. Manic patients generally neglect themselves, in particular their nutrition and hydration. Sometimes they injure themselves through overactivity (e.g. their feet can become sore because they are walking so much, sometimes in bare feet). They may ignore minor injuries which can then become more complicated (e.g. by infection).

The most important investigation is monitoring the physical state of the patient. Manic patients generally neglect themselves, in particular their nutrition and hydration. Sometimes they injure themselves through overactivity (e.g. their feet can become sore because they are walking so much, sometimes in bare feet). They may ignore minor injuries which can then become more complicated (e.g. by infection).

4.14 How should I talk to a manic patient?

Who does your patient trust, or who usually has some influence with them? Try to use this person as well, but be wary of putting such an individual in a difficult position; they may well prefer you to be making the decisions and they will probably already be very fraught, having been kept up all night anyway.

4.15 How is the need for hospitalisation judged?

Get an agreement about treatment and get this started. Checking if the patient is both saying they are willing to take the treatment and also putting this into action is a very important part of the assessment of whether they need to go into hospital. If they are not taking any treatment they will not get better in the near future.

4.16 How is the need for compulsory detention for treatment in hospital judged?

The general assessment about hospitalisation is obviously relevant (see Q 4.15). However, if someone who is manic is not agreeable to going into hospital, then consider invoking legal powers (in England and Wales under the Mental Health Act 1983). The principles in most legal powers are:

4.17 Can other specialist staff help in coping with a manic patient?

The mainstay of community psychiatry in the UK is the community psychiatric nurse (CPN). Experienced CPNs have usually had experience both in the hospital and the community so that they are familiar with a broad range of psychiatric problems and have also managed patients in extreme mental states. They often have a long-term relationship with both patients and their families which can prove invaluable in judging the seriousness of the mania and also what action is appropriate. CPNs are usually familiar with what medications have proved useful previously and how the illness tends to progress. In some cases they will be able to monitor the mental state on a daily basis and ensure that the medication is both available and ingested!

Other members of the Community Mental Health Team include psychologists and occupational therapists. Their role is usually in the longer term care of people with manic depression (see Q 5.45). However these other team members can also be a useful resource in encouraging a manic patient to take some treatment, particularly if they have a strong relationship of trust with a patient or their family.

4.19 Is violence a problem in mania?

Other aspects that need to be borne in mind when assessing violence in any situation are:

4.20 What is the best way to deal with violent behaviour in a bipolar patient?

The first line is to assess the diagnosis and current clinical state. This can be a rapid process in a patient you know well and whose manic symptoms are obvious. If the patient is in an acute episode of mania but acting violently then urgent treatment including sedation is required (see Q 4.9). However, this can only be provided when the situation is safe–in hospital this is usually achieved using experienced and skilled staff in sufficient numbers to physically restrain the patient if this is necessary.

If the situation is not that extreme and you decide it is reasonable to try to intervene, then the first step is to try to just talk–and more importantly listen–to the patient (see also Q 4.14). This gives you a chance to assess the patient’s mental state and establish some rapport. Make sure you do not get into an argument–though this is very easy to do!

4.21 How do I resolve potentially violent situations involving bipolar patients?

Would you like to come to hospital?: It may seem unlikely that this will be accepted but it is worth offering none the less–it may offer a quick solution.

Would you like to come to hospital?: It may seem unlikely that this will be accepted but it is worth offering none the less–it may offer a quick solution. Would you like to take some medicine to calm you down?: Offer a choice of medicines (e.g. diazepam or olanzapine). It may be that if the patient has some control over the choice they would be willing to take some treatment–perhaps even ask them what medicine they think would be helpful.

Would you like to take some medicine to calm you down?: Offer a choice of medicines (e.g. diazepam or olanzapine). It may be that if the patient has some control over the choice they would be willing to take some treatment–perhaps even ask them what medicine they think would be helpful.4.22 What can family and friends do to help a manic patient?

There is a difficult balance to be struck when trying to help someone who is manic. The patient will almost certainly try to persuade you that they are fine and don’t need any intervention. They often do this by a combination of cheerfully trying to get you to go along with them but also by getting irritable and annoyed if they are thwarted. Directly challenging patients often proves counterproductive but trying to make clear to them your view of their illness is important. Maintain your view that they are ill and what they need to do about it, without being drawn too much into argument.

4.23 Is an advance directive helpful when you are managing mania?

Having a good idea of what patients want you to do if they become ill again can be very valuable. An advanced directive is usually a written account of this (see Appendix 2). It will often include who should be involved–for example in the family, primary care or psychiatric staff. It may indicate what should be done about particular risks such as money, including taking away credit cards. The directive can specify what treatment the patient would prefer and hopefully this will have been worked out with a doctor beforehand.

There are plenty of positive uses for an advanced directive; however, they can still prove very difficult to implement. The patient may not accept at all what they have written down and on occasion it has been torn up in front of the doctor! The patient may well feel that it was someone else who really wrote it but felt under duress to agree; even so it gives you some basis to proceed with treatment. Some directives are unreasonably proscriptive–for example specifying who should be involved when they are either not available or not willing when the time arises. The treatment specified may not be appropriate and just because it is written down does not mean that it has to be implemented–you still have the usual responsibilities for your prescriptions. The directive may also specify that the patient does not wish to go to hospital or even that the illness should be allowed to continue its course–again you cannot ignore your responsibilities because of what is written down. If a patient is not capable of making decisions, then you have to act in their best interests, having taken account of all the relevant information that you have. In the end this may include detention through the usual legal channels.

4.24 How can I recognise that I am going manic?

It is often possible to identify a particular sequence of symptoms or behaviours that can act as a ‘relapse signature’ for each individual who experiences episodes of mania. Think back to what happened in the week or two before your illness became obvious. Look at the list of symptoms that occur in mania (see Box 1.1):

Do you get particular ideas when you become manic–either grandiose or paranoid ideas or some very individual ideas (e.g. thinking that naturism should be universally adopted).

Do you get particular ideas when you become manic–either grandiose or paranoid ideas or some very individual ideas (e.g. thinking that naturism should be universally adopted). Ask other people what they notice early on that worries them (e.g. are you getting irritable or getting up very early to go running?).

Ask other people what they notice early on that worries them (e.g. are you getting irritable or getting up very early to go running?).4.25 What can I do to help myself if I think that I am becoming manic?

Hopefully you will have agreed beforehand with your doctor what changes you will make to your treatment when you become manic. If you are on longer term preventive treatment then it may be appropriate to increase this. Alternatively–and particularly if you are not on a long-term treatment–it will be starting an antipsychotic drug which suits you reasonably well and has been effective for you in the past. The short-term use of sleeping pills or tranquillisers might be another option.