CHAPTER 18 Treatment of Lower Eyelid Retraction with Recession of Lower Lid Retractors and Placement of Hard-Palate or Allogeneic Dermal Matrix Spacer Grafts

Treatment of lower eyelid retraction is common in patients with thyroid ophthalmopathy. It may also occur as a complication of previous blepharoplasty procedures, both cosmetic and functional. Treatment consists of recessing the lower lid retractors and placing a spacer between them and the inferior tarsal border. Present options include hard-palate grafting for the spacer because (1) it provides a mucous membrane lining to the internal lower lid; (2) it is rigid and flat; and (3) it is autogenous. A useful alternative however is using an allogeneic spacer graft to avoid issues relating to harvesting and also to reduce operative time.

A lower internal blepharoplasty along with lower retraction surgery is commonly performed. This approach differs slightly from the transconjunctival approach to resection of lower eyelid herniated orbital fat (see Chapter 14), in that the retractor incision is made at the inferior tarsal border rather than 5–6 mm inferior to the inferior tarsal border.

Most patients who present with dissatisfaction after lower blepharoplasty complain or have symptoms related to lower eyelid malposition combined with a more ‘round’ appearance to the eye that is secondary to an increased vertical palpebral aperture and a shortened horizontal aperture. Often, mild to even moderate degrees of lower eyelid retraction need not be addressed depending upon the patient’s concerns, desires and expectations. Frequently, lower eyelid retraction is minimal and can be ignored. If, for instance, the patient with thyroid disease undergoes an orbital decompression for treatment of exophthalmos, the eye will commonly descend, thus making the lower eyelid retraction less apparent. If the retraction is moderate to severe and a decompression is not in the picture, the lower eyelid retraction should be treated. If a patient presents with lower eyelid retraction after blepharoplasty that is mild and without symptoms, they may have options for correction that are dependent upon what they are willing to endure regarding the surgical procedure, recovery, and final result.

Another method involves measuring the distance from a light reflex that is made to shine on the cornea to the lower lid as both patient and examiner look in the primary position of gaze, that is, the margin reflex distance-2 (MRD2) (see Chapter 3, Fig. 3-9).1 Normally, the lower eyelid rests at the inferior limbus. Measurements of retraction greater than 2 mm may be enough to warrant retraction surgery.

Preparation before surgery (with the implementation of a hard palate graft)

At some time before surgery, it is our preference when a hard palate graft is the chosen spacer graft, to work with a dentist who constructs a custom-fitted plastic plate that will fit onto the roof of the patient’s mouth.2,3 This plate is attached to several teeth with extensions that come off the plastic plate. After retrieval of the hard-palate grafts and the placement of an absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) to the donor site, the plastic plate is inserted onto the roof of the mouth. The plate provides comfort and maintains hemostasis.

Surgical technique

Hard palate harvesting and grafting

Local anesthesia with intravenous sedation is usually used. Topical tetracaine is applied over the eye. A corneo-scleral contact lens is placed over the eye and under the upper and lower eyelids to protect the eye and minimize the patient’s discomfort from the operating lights. The patient is prepared and draped in the usual fashion, similar to that used for upper or lower blepharoplasty (see Chapters 7, 14 and 16). The mouth is prepared with povidone-iodine (Betadine) sponges rubbed over the teeth, hard palate, and tongue surface.

Recessing the lower eyelid retractors

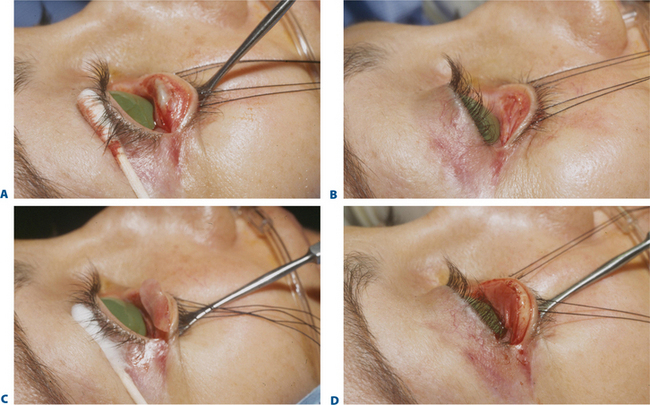

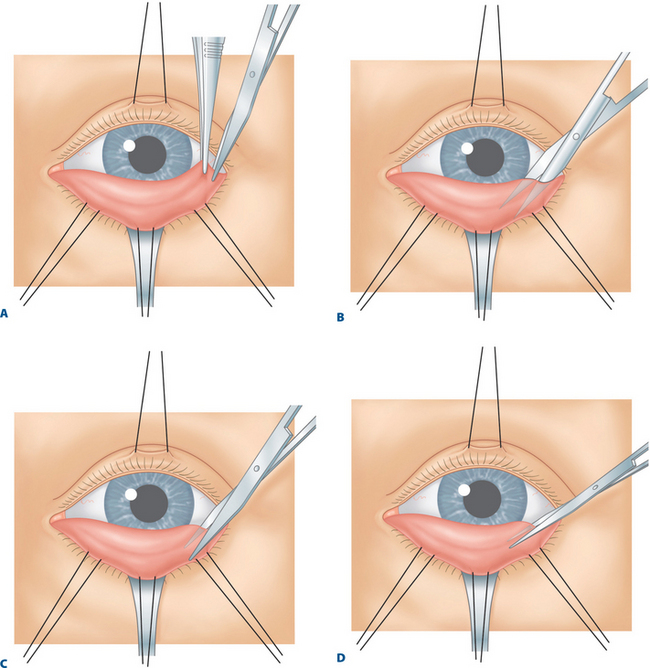

A toothed forceps grasps the conjunctiva, Müller’s muscle, and the capsulopalpebral fascia at the temporal aspect of the eyelid, just beneath the inferior tarsal border (Fig. 18-1A). With a Westcott scissors, the surgeon penetrates this tissue and severs it from the inferior tarsal border. The Westcott scissors enters this opening and passes between capsulopalpebral fascia and orbicularis muscle across the eyelid (Fig. 18-1B). The surgeon facilitates this maneuver by separating the Westcott scissors blades during the passage and by pulling the scissors upward toward the conjunctival surface. At the same time, the surgeon’s assistant is releasing the Desmarres retractor slightly or pulling the skin surface outward. Because skin (and scar tissue in previously operated lower eyelids) is firmly attached to the orbicularis muscle and the conjunctiva is firmly attached to Müller’s muscle and capsulopalpebral fascia, the two lamellae separate in opposite directions during this maneuver.

D, The scissors is rotated below the tarsal border.

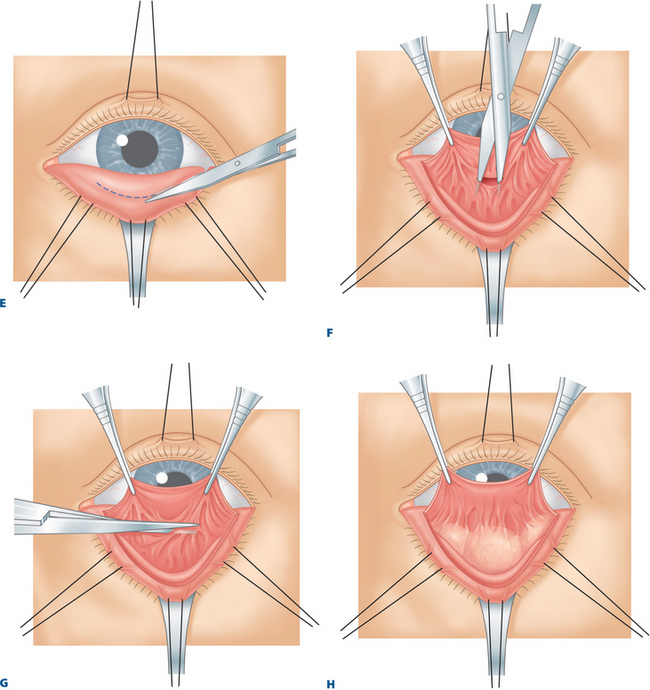

H, Herniated orbital fat is exposed between the capsulopalpebral fascia and the septum.

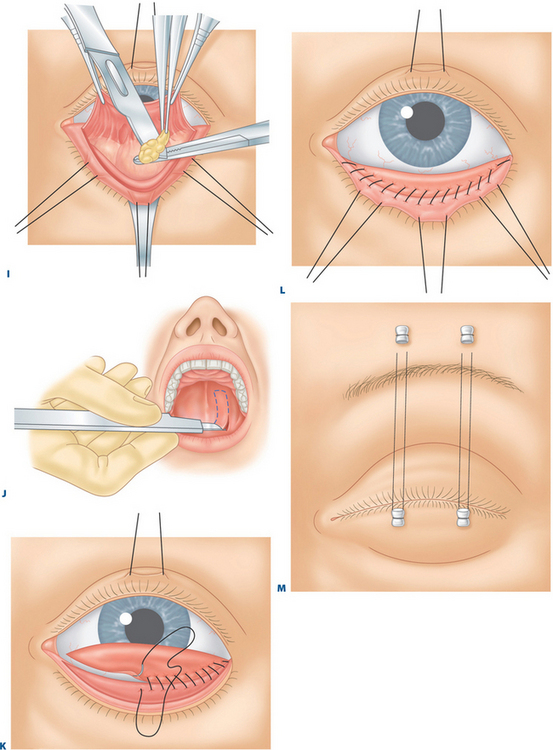

I, Herniated orbital fat is severed.

J, A hard-palate mucosal graft is harvested from the roof of the patient’s mouth.

L, The hard-palate graft is sutured to the inferior tarsal border.

M, With 4-0 black silk sutures, the lower eyelid is pulled upward toward the eyebrow.

While the eyelid structures are kept in these positions, the Westcott scissors is withdrawn and one blade is reinserted into the separated plane. Using the scissors, the surgeon severs the conjunctiva, Müller’s muscle, capsulopalpebral fascia, and scar tissue where present just beneath the inferior tarsal border (Figs 18-1C to 1E). During this step, the surgeon must be careful to minimize incision of the orbicularis muscle, as this can interfere with the vascular supply to the eyelid margin and cilia, which might result in visible surface (and other soft tissue) contour abnormalities and the loss of eyelashes. When first learning this technique, the surgeon should sever the conjunctiva and Müller’s muscle in one step and the capsulopalpebral fascia in another step.

A toothed forceps is used to grasp the central conjunctiva, Müller’s muscle, and the capsulopalpebral fascia. The surgeon pulls these tissues in a direction towards the eye, while the assistant pulls the skin and orbicularis muscle away from the eye with the 4-0 black silk suture attached to the lower eyelid or with the eyelid everted over a Desmarres retractor. A Westcott scissors is used to penetrate the area between these retracted lamellae (Fig. 18-1F). The scissors should fall into the suborbicularis space. At this step, the surgeon should be able to visualize the white capsulopalpebral fascia surface on the internal surface and the reddish orbicularis muscle on the outer surface. These landmarks are less easily visualized in the previously operated eyelid.

While still keeping the eyelid structures pulled in these directions, the surgeon uses the Westcott scissors to separate the remaining nasal and temporal tissues (Fig. 18-1G). (The Westcott scissors should hug the capsulopalpebral fascia surface rather than the orbicularis muscle surface.) Alternatively, this separation can be accomplished with a Colorado needle, a laser, or a disposable surgical (battery-operated) cautery (Solan Accu-Temp, Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville, FL). Bleeding is controlled with a disposable cautery.

Excision of herniated orbital fat

A small Desmarres retractor is used to evert the lower eyelid and pull skin and the orbicularis muscle outward away from the eye. With the use of cotton-tipped applicators, the temporal, central, and nasal orbital fat pads are isolated and the inferior oblique muscle is identified (Fig. 18-1H). The capsule of the fat pads is then opened.

Fat that prolapses with general pressure can be excised or transposed. If excised, it may be clamped with a hemostat (AMP), and the tissues held in the hemostat are cut free by running a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade over them (Fig. 18-1I). Cotton-tipped applicators are applied under the hemostat, and a Bovie cautery is applied to the fat stump. As the hemostat is released, the surgeon grasps and inspects the fat stump to make sure that there is no bleeding before allowing the fat pad to retract into the orbit. This maneuver is continued temporally, centrally, and nasally until fat no longer prolapses with general pressure applied on the eye.

Obtaining the hard-palate graft

A No. 15 Bard-Parker blade is used to incise the outlined areas of the hard-palate donor site (Fig. 18-1J). The Bard-Parker blade and a No. 66 Beaver blade are used to remove the hard-palate graft. The assistant pushes the tongue downward and suctions blood from the graft site during this step. Suction must also be maintained in the posterior pharynx to prevent the patient from swallowing any blood or saliva.

Bleeding is controlled with an absorbable gelatin sponge applied to the graft site. Occasionally, one must use microfibrillar collagen hemostat powder (Avitene). The gelatin sponge is pushed up against the hard palate with a tongue blade or the surgeon’s finger for several seconds, and the mouth retractor is removed. Then the hard-palate prosthesis, custom constructed preoperatively, is applied over the roof of the mouth.4,5

Suturing the hard-palate graft to lower eyelid retractors and tarsus muscle

The inferior edge of the graft is sutured to the lower eyelid retractors with a 5-0 chromic catgut suture run nasally to temporally (Fig. 18-1K). Each bite of the suture passes through the lower lid retractors and then the inferior edge of the hard-palate graft. The graft is placed so that the internal surface of the graft facing the eye is the mucosa-lined tissue.

The contact lens is removed, and the lower eyelid is placed in normal position. The surgeon judges the amount of excessive hard-palate graft that extends above the lower eyelid margin and trims this tissue off. Because it is usually better to have a slightly excessive hard-palate graft rather than a sparse one, the trimming of the excessive tissue should be done sparingly.

Next, the superior edge of the hard-palate graft is secured to the inferior tarsal border with another 5-0 chromic catgut suture (Fig. 18-1L). The suture is run continuously nasally to temporally and with the temporal and nasal knots buried deeply.

A suture tarsorrhaphy is formed nasally and temporally, with two 4-0 black silk, double-armed sutures. Each suture passes through the skin and orbicularis muscle of the lower eyelid and exits through the gray line. The sutures then enter the skin and orbicularis muscle above the eyebrow (Fig. 18-1M).

Suturing the allogeneic dermal graft to lower eyelid retractors and tarsus muscle

The suturing of this graft is very similar to how the hard palate graft is sutured to the recipient bed. In the case of post-blepharoplasty lower eyelid retraction (regardless of the graft composition), one must be certain to release the entire cicatrix that allows for the most likely reversal of the lid malposition as well as optimal sizing of the donor graft (Fig. 18-2). A canthoplasty can be performed simultaneously with the placement of either the hard palate graft or allogeneic graft (see Chapter 15).5,6 A suture tarsorrhapy is also placed as with the hard palate graft (medial and lateral) and patching is optional. Traction (frost-type) sutures may also be placed for the first several days.7

Postoperative care

Results

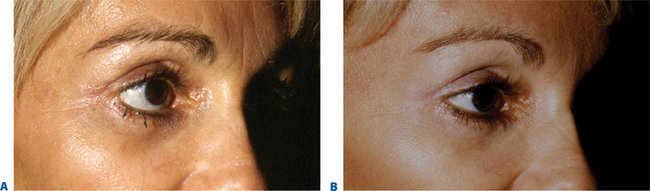

Collectively, we have treated lower eyelid retraction in thyroid disease and post blepharoplasty situations in over 300 eyelids. Approximately 100 of these procedures have been completed with hard-palate grafts, more than 100 procedures utilized acellular dermal grafts, and the remainder involved the use of sclera or ear cartilage (Figs 18-3 to 18-5). Results were superior with hard-palate grafting or dermal grafts, and complications were minimal. In no patient was there a need to add or remove the hard palate. In a select few acellular dermal grafting was repeated within the first year for loss of affect from rapid graft resorption.

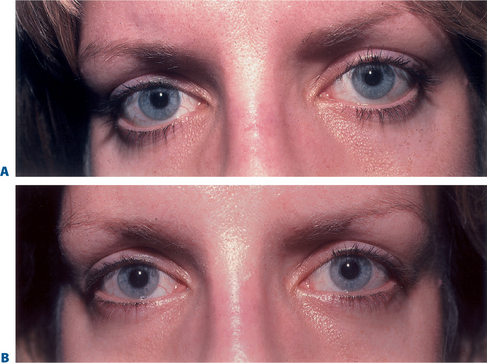

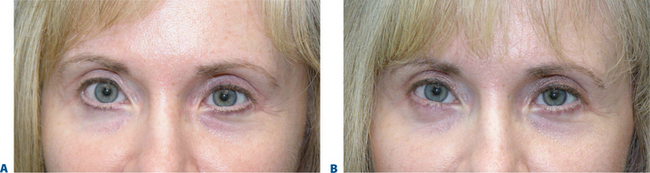

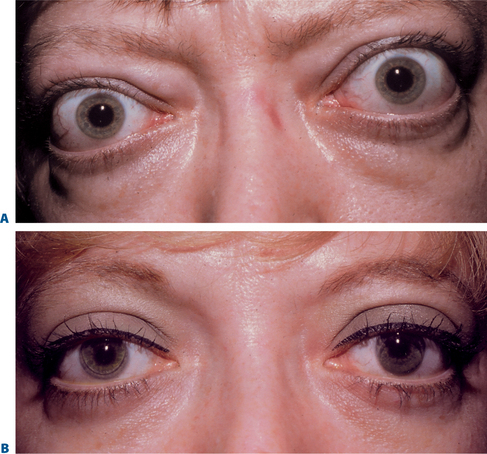

Figure 18-3 A, Preoperative appearance of a patient with thyroid-related retraction of all four eyelids associated with lower eyelid herniated orbital fat. B, Same patient after lower lid elevation by recession of the retractors, placement of a graft between the retractors and the inferior tarsal border, and internal fat excision. The upper eyelids were lowered simultaneously by excision of Müller’s muscle and recession of the levator aponeurosis through an internal approach (as described in Chapter 13), and lateral tarsorrhaphies were performed.

In most cases, this procedure has successfully relieved lower lid retraction, improved the aesthetic appearance of the lower periorbita, and reduced the patient’s ocular irritation, and keratopathy (Figs 18-6 to 18-8).

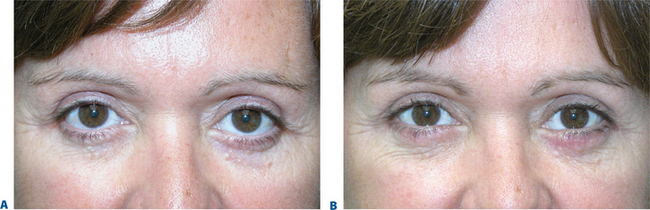

Figure 18-8 A, Pre-operative appearance of a patient with thyroid ophthalmopathy with severe upper and lower eyelid retraction, exophthalmos, exposure signs and symptoms, desiring correction and aesthetic enhancement. B, Six months post-operative appearance after upper eyelid retractor recession (see Chapter 13), lower eyelid retractor recession with Dermaplant spacer grafts, and lateral retinacular suspension canthoplasty.

1 Putterman AM. Basic oculoplastic surgery. In: Peyman G, Sanders D, Goldberg MF, editors. Principles and Practices of Ophthalmology, vol 3. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1980:2248.

2 Mauriello JAJr., Wasserman B, Allee S, et al. Molded acrylic mouthguard to control bleeding at the hard palate graft site after eyelid reconstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;113:342-344.

3 Shorr N, Enzer YR. Letter to the editor re Mauriello JA Jr, Wasserman B, Allee S, et al: Molded acrylic mouthguard to control bleeding at the hard palate graft site after eyelid reconstruction. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:779-780.

4 Terino EO. Alloderm acellular dermal graft. Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:83-99.

5 Fagien S, Elson ML. Soft tissue augmentation with allogeneic human tissue collagen matrix (Dermalogen and dermaplant). Clin Plast Surg. 2001;28:63-81.

6 Fagien S. Algorithm for canthoplasty. The lateral retinacular suspension: A simplified suture canthopexy. Plast Reconst Surg. 1999;103:2042.

7 Fagien S. Tarsorrhaphy and eyelid traction sutures. In: Levine MR, editor. Manual of Oculoplastic Surgery. Edinburgh: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1996:183-187.