CHAPTER 16 Treatment of Lower Eyelid Dermatochalasis, Herniated Orbital Fat, and Hypertrophic Orbicularis Muscle

Skin-Muscle Flap Approach

A skin-muscle flap approach to removal of lower eyelid skin and fat was my favorite approach until about five or so years ago. I now believe that whenever the orbicularis oculi muscle can be preserved, there are advantages in eliminating postoperative eyelid retraction and ectropion as well as possibly decreasing postoperative edema from lymphatic drainage interruption. I, therefore, find that I am removing or repositioning lower eyelid orbital fat through an internal transconjunctival approach and removing and tightening lower eyelid skin through a skin flap approach combined with a lateral orbicularis flap lift. I tend to limit the skin-muscle flap approach to selected patients who have excessive lower eyelid skin and orbicularis usually associated with cheek bags and festoons who choose not to have a cheek–midface lift (Chapter 17). It is also useful when combined with a capsulopalpebral advancement entropion procedure. It is also rare that I do this approach without combining it with a lateral canthal tendon tightening through a tarsal strip procedure. I do believe that in a textbook on cosmetic oculoplastic surgery, it is important to include all forms of treatment including techniques that are more rarely done.

Surgical technique

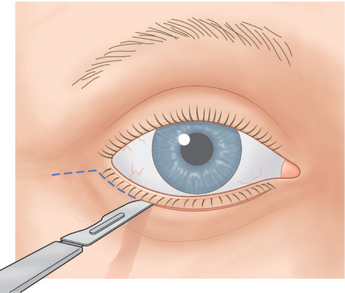

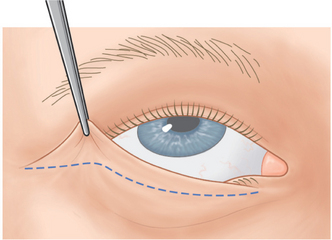

A No. 15 Bard-Parker blade is used to make a skin incision 1.5 mm beneath the lower lid lashes (Fig. 16-1). The incision begins below the punctum and extends temporally for a distance of 2–3 mm temporal to the lateral canthus. The incision is extended for another 1 cm in an almost horizontal direction.

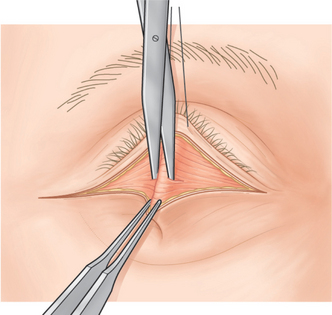

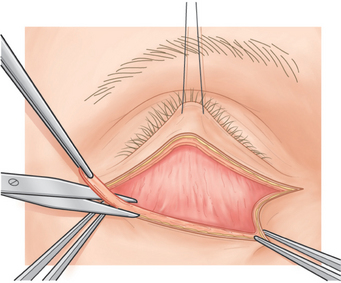

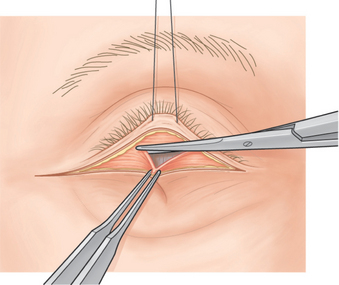

A 4-0 black silk traction suture is placed through skin, orbicularis muscle, and superficial tarsus of the central lower eyelid and is used to pull the lower eyelid upward. With a toothed forceps, the surgeon grasps the central lower lid at the skin incision site and pulls the eyelid downward and outward. A Westcott scissors is used to penetrate the central orbicularis muscle, with the scissors tips pointed inward and downward (Fig. 16-2). The suborbicularis space should be seen. The Westcott scissors is inserted into the space, and its blades are spread to elongate this dissection.

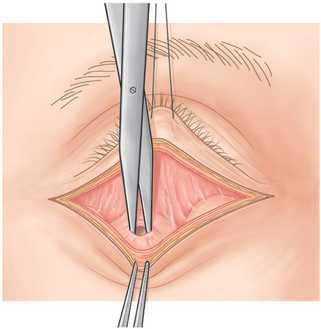

The traction suture and forceps are kept in the same position as the orbicularis muscle is severed along the incision site with Westcott scissors (Fig. 16-3) or other suitable instrument. A disposable cautery (Solan Accu-Temp, Xomed Surgical Products, Jacksonville, FL), Colorado needle, sapphire-tipped scalpel neodymium : YAG laser, or carbon dioxide laser (see Chapter 22) can also be used.1 These four instruments coagulate blood vessels while they simultaneously cut the orbicularis muscle.

Figure 16-3 The orbicularis oculi muscle is severed along the skin incision site with Westcott scissors.

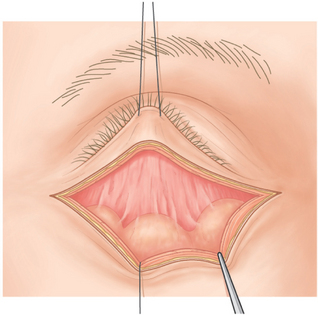

Blunt dissection with a cotton-tipped applicator or Westcott scissors is applied under the orbicularis muscle (Fig. 16-4). This step should allow visualization of the nasal, central, and temporal herniated orbital fat pads (Fig. 16-5).

A 4-0 black silk traction suture is placed through the orbital septum and is used to pull the lower lid skin flap downward. It is secured to the drape with a hemostat. The lower eyelid is pulled upward with the central traction suture, which is attached to the superior drape. Any remaining bleeding vessels are coagulated with a disposable cautery.

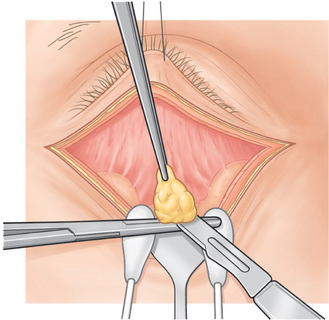

A Westcott scissors or disposable cautery is used to make a small opening in the temporal orbital fat capsule. The surgeon pushes on the eye and the fat that prolapses with gentle pressure applied to the eye is clamped with a hemostat, and the tissues above the hemostat are cut with a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade that is slid over the hemostat (Fig. 16-6). Cotton-tipped applicators are applied under the hemostat, and a Bovie cautery is used to coagulate the fat stump. Before releasing the hemostat, the surgeon grasps the orbital fat beneath the hemostat with a forceps. The fat is inspected for bleeding before it is allowed to retract into the orbit. Bleeding can lead to retrobulbar hemorrhage and the potential for blindness.2

Figure 16-6 Fat is clamped with a hemostat and cut with a No. 15 Bard-Parker blade slid over the hemostat.

After the temporal orbital fat pad is removed, the surgeon pushes on the eye again to ensure that the entire pad has been removed. Commonly, after removal of the temporal orbital fat pad, a second temporal fat pad appears when the surgeon pushes on the eye. This may be a second temporal fat pad that is not apparent until the first pad is removed, or it may be a deeper portion of the temporal fat that becomes visible after the anterior part is removed.3 In either case, the surgeon must remove the second pad in order to prevent postoperative fullness in the temporal aspect of the eyelid. Once the temporal fat is completely removed, the central and nasal fat pads are removed in a similar manner. The central and nasal fat pads are separated by the inferior oblique muscle, and the nasal fat pad is white.

The patient is then asked to look upward while the lower lid skin-muscle flap is draped over the incision site (Fig. 16-7). If the patient is sedated, the assistant pushes on the eye by applying pressure to the scleral protective lens. This causes the lower eyelid to elevate and simulates the lower eyelid position in upgaze. The skin and orbicularis muscle that drape over the incision site are excised with Westcott scissors. This excision is performed temporally over the lateral canthal incision site and then horizontally over the incision site of the lower lid skin from lateral canthus to punctum.

With two toothed forceps, the surgeon grasps the skin-muscle flap nasally and temporally and pulls it downward. A strip of orbicularis muscle is routinely excised over the superior skin-muscle flap temporally to nasally for a distance of 4–5 mm beneath the flap (Fig. 16-8). (This prevents postoperative fullness in that area.) If orbicularis muscle is noted to be hypertrophic preoperatively, it is now excised over the sites noted preoperatively in the same manner as the strip that is routinely taken. Bleeding is controlled with a disposable cautery.

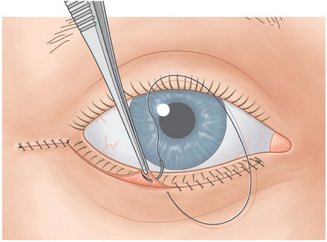

The surgeon sutures the skin by running a 6-0 black silk suture continuously from the lateral canthus to the temporal end of the incision site. A second 6-0 black silk suture is run continuously from the nasal end of the incision to the lateral canthus (Fig. 16-9). Several 6-0 interrupted Vicryl sutures are used to reinforce the temporal incision.

Postoperative care

For two to three hours postoperatively the patient applies cold compresses to the eyelids. Ophthalmic signs are closely observed. The recovery room staff checks the patient every 15 minutes for the ability to count fingers and to make sure there is no severe pain or proptosis. If the patient demonstrates either an inability to count fingers, proptosis, or complains of severe pain, the surgeon is called immediately, because these problems may indicate a retrobulbar hemorrhage, which has the potential to cause blindness.2 For 24 hours postoperatively the patient or the patient’s family continues to apply cold compresses to the eyelids and check for the ability to count fingers every hour (other than during sleep). If a patient cannot count fingers or if there is severe pain or proptosis, he or she should immediately return to the Surgical Facility or other Emergency Facility for evaluation of a possible retrobulbar hemorrhage.

Postoperative complications

Lower eyelid ectropion and retraction are possible complications from lower external blepharoplasty. Usually, these complications can be prevented by careful preoperative assessment of patients with horizontal eyelid laxity who have the potential for development of these problems and by a simultaneous tarsal strip procedure in these patients (see Chapter 17). Should these complications occur, however, they can be treated with a tarsal strip postoperatively (see Chapter 17).

If too much skin is removed, a cicatricial ectropion can occur. If this happens, skin grafting or a cheek lift, in addition to the tarsal strip procedure, is needed (see Chapter 17).

Results

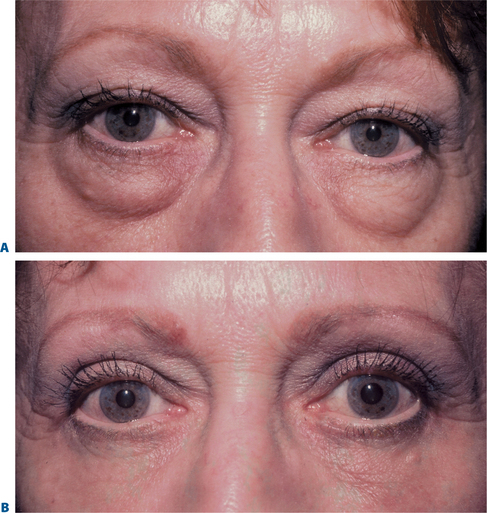

More than 3000 patients have been treated with this technique with excellent results (Fig. 16-10).

1 Putterman AM. Scalpel neodymium : YAG laser in oculoplastic surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990;109:581-584.

2 Putterman AM. Temporary blindness after cosmetic blepharoplasty. Am J Ophthalmol. 1975;80:1081-1083.

3 Putterman AM. The mysterious second temporal fat pad. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1985;1:83-86.