Chapter 46 Treatment of liposuction complications

• Correction after the occurrence of a complication in lipoplasty is very difficult, hence prevention of complications is crucial.

• Surgical tips for preventing complications are given (see video clip 1).

• Maintainance of the multiple spheres and angles of the body rather than converting the region into a single plane is important.

• Perform circumferential liposuction using a smaller diameter cannula.

• Superficial suction leads to dimple depression (“contour irregularities”). Deep suction leads to adhesions.

• Perform serial liposuction procedures rather than large volume liposuction.

• Prevent lethal complications, using the time gap protocol.

Introduction

Numerous cannulae and instruments have been introduced for use in liposuction.1–3 The tumescent technique and the concept of ultrasonic or laser lipolysis are now widely accepted to assist in more advanced and safe liposuction procedures.4 Even with the considerable advancements in techniques aided by various new instruments, the complications related to liposuction, however minor, are still a concern.5 Moreover, numerous previous studies in the literature have focused on and highlighted safety considerations in liposuction. There is a lack of strategy and treatment guidelines for complications of liposuction. In this chapter, a good guideline for the treatment of complications from liposuction is provided, which range from life-threatening to esthetic complications.

Complications and Their Management

Life-threatening or Systemic Complications

Fat Embolism Syndrome (FES)

Diagnosis using ventilation–perfusion scan may show the matching defects.6–8 Differential diagnoses include fluid overload, pulmonary edema, aspiration pneumonia and various other causes of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).9 Most of all, differentiation of FES from pulmonary embolism is important because the treatment is very different. Heparin can be harmful, for obvious reasons, in the early management of FES.

Treatments using intravenous ethanol, heparin, and low molecular weight dextran have largely fallen from favor. Medical management now consists mainly of high-dose corticosteroids, which have been shown to prevent the development of FES in several prospective randomized trials.10–12 The role of corticosteroids is considered to inhibit the inflammatory reaction to the presence of fat in the circulatory system after liposuction.

Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT) and Pulmonary Embolism (PE)

There are three major factors that are important in the development of DVT and PE. The first is the development of venous stasis, the second is the activation of a blood coagulation cascade, and the third is injury to the vascular endothelium (Virchow’s triad).13

Initial therapy consists of intravenous heparin, usually by a bolus dose of 5000 to 10 000 U.

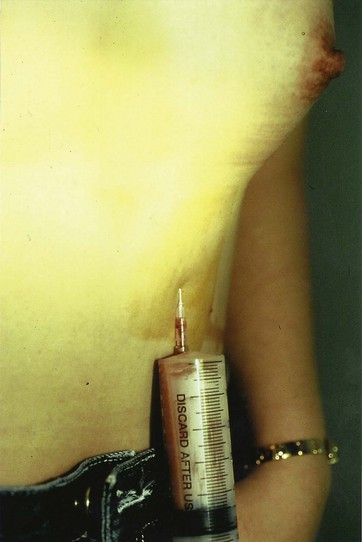

Extended Infection

Liposuction involves heavy manipulation of the superficial fascial system, resulting in the possibility of ascending infections via the fascial system, and there have been reports of necrotizing fasciitis from these procedures.14 Although infection in simple liposuction cases is rare, combined procedures including abdominoplasty and brachioplasty for reduced skin laxity may cause serious infections. Hematomas and seromas can become sources of infection, hence meticulous hemostasis and drainage of seromas is important to prevent infection (Figs 46.1 and 46.2). Moreover, maintaining aseptic techniques throughout the procedure is of utmost importance, especially during positional changes of the patient.

Hypovolemia/Anemia

Tumescent infiltration provides profound hemostasis in large volume liposuction.15 Bloodless aspiration virtually eliminates the possible sequelae of shock and hypovolemia. The ideal ratio of subcutaneous fluid to total aspirate is controversial. The surgeon must weigh the risks between excessive blood loss (inadequate subcutaneous fluid) and pulmonary edema (excess subcutaneous fluid). Fluid shifts between interstitial fluid and plasma volume can result in intravasation (hypervolemia) or extravasation (third spacing). Excessive infiltration obviously should be avoided. According to our 14-year experience with 2398 cases, the need for blood transfusions is rare. It must be remembered that 2000 ml aspiration of supernatant fat is regarded as a decrease in hemoglobin count by 1. Some of the drawbacks of blood transfusions include potential infection, transfusion mismatch, circulatory overload, microthrombi, and postoperative anemia.

Healthy normovolemic patients can tolerate a moderate reduction in hemoglobin count with multiple compensatory mechanisms. In clinical settings, normal tissue oxygenation is maintained with hematocrits as low as 20, if the subject is healthy and remains normovolemic.16

Lidocaine Toxicity

Early signs and symptoms of lidocaine toxicity include lightheadedness, restlessness, drowsiness, tinnitus, slurred speech, metallic taste in the mouth, and numbness of the lips and tongue. These subjective signs may be seen at plasma levels between 3 and 6 µg/ml. Shivering, muscle twitching, and tremors may occur as plasma levels reach 5–9 µg/ml, followed by convulsions, CNS depression, and then coma at plasma levels greater than 10 µg/ml. As levels increase above this, respiratory depression and eventually cardiac arrest can occur.17

Esthetic Complications

Contour Irregularities (Figs 46.3–46.7)

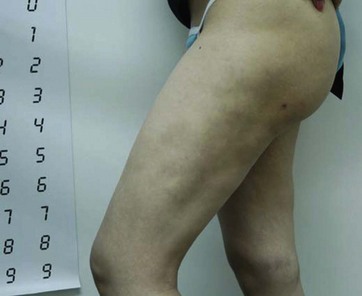

FIG. 46.5 Contour irregularities on lateral aspect of thigh with induction of fibrous and dense tissues.

FIG. 46.6 Severe contour irregularity at the trunk and thigh regions.

(From Kim YH, et al. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: A review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:863–871. with permission.)

FIG. 46.7 Postoperative contour irregularity at the submental area in a patient with severe skin laxity.

A member of the surgical team should keep a chart with the same markings as on the patient and note the amount of aspiration from each area. By keeping the preoperative photographs visible during surgery, the surgeons should be aware of what the deformities looked like while the patient was in a standing position. Poor position of the patient on the operating table can be the cause of the irregularities.18 During liposuction, it is important to set the maximum vacuum pressure between 250 and 400 mmHg, in order to prevent over-resection and destruction of normal adipose architectures, which are the main causes of contour irregularities.

Pinto et al divided the fatty layers into two: superficial dense and deep loose areolar layers.3 This concept is well established in the recent era. Compared to the deep adipose layer, the superficial adipose layer has minimal fatty tissues.19 Overzealous suctioning or manipulation of the superficial layer can cause complications. However, Illouz et al identified a further intermediate layer. The intermediate layer exists in the subdermal fat, approximately 5 mm below the skin. Intermediate level liposuction results in more skin retraction than does deeper level suctioning and in fact produces almost the same amount of contraction as superficial suctioning, without the risk of complications.1,20,21 Suctioning of the superficial layer should be done minimally to avoid complications such as skin irregularities and ischemia, with focus on suctioning the intermediate layer and detaching the superficial layer above from the underlying tissues to achieve maximal skin redraping.

For prevention of postoperative contour irregularity, Gasperoni2 recommended that the progression of the cannula gauge in use be made from small to large. However, for the refinement and final contouring of the superficial layer, a decreasing gauge size order is more convenient.2,19

According to our series, decreased complication rates resulted after the introduction of ultrasonic energy (UAL, ultrasound-assisted liposuction). In particular, the incidence of contour irregularities has decreased significantly since using UAL.19 Ultrasound emits energy to the area corresponding to the area of its probe, and resolves thick and fibrous subcutaneous connective tissues. Compared to the linear movement of the suction tip of the power-assisted liposuction (PAL) alone, it seems that the ultrasound delivers the energy more evenly on the suctioned area (Fig. 46.8 and video clip 1).

There are some debates regarding immediate correction and delayed correction of contour deformities after superficial liposuction. In fact, it is very difficult to precisely evaluate the sunken areas and the areas with insufficient fat removal during the surgery. Hence delayed correction, after all the healing process has finished, is generally accepted.21 If too much fat is aspirated from a localized point to a visible level during the procedure, Gasperoni2 recommended correction of the depression immediately by injecting some of the aspirated fat.

Our strategies regarding management of contour irregularities involve both immediate and delayed correction techniques. According to our experience, when severe sunken deformities are found during surgery, the outcome becomes more exaggerated and it often leads to asymmetry of the body. Hence, when we find such deformities of the intermediate and deep adipose layers, using the pinch, pizzaiolo test, and the refinement test during surgery (Figs 46.9 and 46.10), we try to correct it immediately. Afterwards, refinement or secondary touch operations are also considered and proceeded with after the healing process is finished. Balanced application of immediate and delayed corrections regarding contour irregularities can yield more esthetic final outcomes, which leads to increased patient satisfaction.

A new concept was introduced recently. Saylan was the first to describe a technique called “liposhifting” as a safe and simple method to treat contour irregularities.22 The fat is loosened around and under the defect with the cannula, not applying suction and obstructing the open end with a finger or a plug (Fig. 46.11). Some cannulas may be more aggressive than the blunter tipped ones, but crisscross and fan-shaped patterns with multiple layers should be utilized. The subdermal tissues in the area of the defect are treated in the same manner as the surrounding fat, by utilizing tunnels with no sweeping motions. The fat in the surrounding tissues is moved or shifted into the defect by rolling a cannula over the tissue with moderate pressure until the defect is at least flat. Fat can also be mobilized by massage. Resuctioning, fat grafting and fat shifting are useful tools for correcting contour irregularities, and since several procedures are always required, informed consent is also crucial in the treatment.23

Inner Thighs

This area is difficult to treat as it presents tissue with not only less tension and more skin flaccidity but also more restricted access and mobilization, since it has important anatomic structures. Nevertheless, we routinely proceed with superficial liposuction.24

Buttocks

Most surgeons have regarded the buttocks as having redundant fat, hence they are an uncommon area for contour irregularities to occur. However, we have seen many complicated cases in this area (Fig. 46.12).

This is an area subject to trauma, so the fat tissue in this area should not be diminished. Its loose collagen makes the fatty structures weaker, so that lipoplasty may result in flaccidity. Therefore, we prefer to suction only the periphery to improve its contour, and use a 3 mm cannula superficially.25

Skin Necrosis

There are a variety of factors causing skin loss, the most important of which is smoking. The next most important factor is improper intraoperative management of fluid replacement, resulting in impairment of the microcirculation in the elevated flaps (Figs 46.13 and 46.14). Patients should be encouraged to cease smoking at least several weeks before the procedure, and patients undergoing suctioning in their lower extremities should be warned thoroughly of the risks of nicotine-induced skin necrosis. The other main cause is the application of circular compressive garments which can be too tight and can induce a stasis that induces DVT and ensuing pulmonary emboli. To avoid compression, the garment must be <24 mmHg (venous pressure), but >18 mmHg to be efficient. In practical terms, the garment should be easy to put on and to remove26 (Fig. 46.15).

Seromas

There were reports about UAL being associated with a somewhat higher incidence of seroma formation.19,27 Seromas are extremely rare in PAL-alone procedures. They usually occur when liposuction is combined with traditional body contour operations. Pseudobursae occur in undermined spaces where there is repeated fluid formation and accumulation even after aspiration or drainage. The incidence appears to have increased with the greater number of outpatient combined SAL and body contour procedures. It is rare to see a pseudobursa after liposuction, but more commonly after large abdominoplasty procedures.

The placement of drains after the procedure and frequent clinical follow up are recommended for careful examination of seroma formation (Fig. 46.16). Administration of antibiotics may be required for prevention of infection.

Hyperpigmentation (Fig. 46.17)

Asymmetry (Fig. 46.18)

FIG. 46.18 Overzealous suction on bilateral thigh resulted in contour irregularity and asymmetry.

(From Kim YH, et al. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: A review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg 2011;127:863–871, with permission.)

Symmetric positioning of the patient on the operation table is important.

1 Illouz YG. Illouz’s technique for body contouring by lipolysis. Clin Plast Surg. 1984;11:409–417.

2 Gasperoni C, Gasperoni P. Subdermal liposuction: Long-term experience. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:63–73.

3 Pinto EB, Indaburo PE, Muniz Ada C, et al. Superficial liposuction. Body contouring. Clin Plast Surg. 1996;4:529–548.

4 Mann MW, Palm MD, Sengelmann RD. New advances in liposuction technology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2008;27:72–82.

5 Gasparotti M. Superficial liposuction: a new application of the technique for aged and flaccid skin. Aesth Plast Surg. 1992;16:141–153.

6 Christman KD. Death following suction lipectomy and abdominoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1986;78:428.

7 Laub D, Jr., Laub D. Fat embolism after liposuction. Ann Plast Surg. 1990;25:48–52.

8 Ross R, Johnson GW. Fat embolism after liposuction. Chest. 1988;93:1294–1295.

9 Skarzynski JJ, Slavin JD, Jr., Spencer RP, et al. Matching ventilation perfusion images in fat embolism. Clin Nucl Med. 1986;11:40–41.

10 Alho A, Saikku K, Eerola P, et al. Corticosteroids in patients with a high risk of fat embolism syndrome. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;147:358–362.

11 Lindeque BG, Schoeman HS, Dommisse GF, et al. Fat embolism and the fat embolism syndrome: A double blind therapeutic study. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69:128–131.

12 Schonfeld SA, Ploysongsang Y, DiLisio R, et al. Fat embolism prophylaxis with corticosteroids: A prospective study in high risk patients. Ann Intern Med. 1983;99:438–443.

13 Hull RD, Raskob GE, Firsh J. Prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism: an overview. Chest. 1986;89:374s–383s.

14 Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal outcomes from liposuction: Census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:436–446.

15 Klein JA. The tumescent technique for local anesthesia improves safety in large volume liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1085–1098.

16 Singh G, Chaudry KI, Chaudry H. Crystalloid is as effective as blood resuscitation of hemorrhagic shock. Ann Surg. 1982;215:377–382.

17 Samdal F, Amland PF, Bugge JF. Plasma lidocaine levels during suction-assisted lipectomy using large doses of dilute lidocaine with epinephrine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:1217–1223.

18 Toledo LS, Mauad R. Complications of body sculpture: prevention and treatment. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:1–11.

19 Kim YH, Cha SM, Naidu SK, et al. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: A review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:863–871.

20 Illouz YG. Present results of fat injection. Aesth Plast Surg. 1988;12:175–181.

21 Illouz YG. Body contouring by lipolysis: A 5-year experience with over 3000 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1983;72:591–597.

22 Saylan Z. Liposhifting: treatment of postliposuction irregularities. Int J Cosm Surg. 1999;7:71–73.

23 Shiffman MA, Blugerman G. Fat shifting for the treatment of skin indentations. In: Shifman MA, Di Giuseppe A. Liposuction Principles and Practice. Heidelberg: Springer; 2006:354–356.

24 Bolivar de Souza Pinto E, Erazo IPJ, Prado Filho FS, et al. Superficial liposuction. Aesth Plast Surg. 1996;20:111–122.

25 Bolivar de Souza Pinto E, da Silva Moia SM, Machado MN, et al. Morphohistologic analysis of fat tissue in areas treated with lipoplasty. Aesth Surg J. 2002;22:513–518.

26 Illouz YG. Complications of liposuction. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33(1):129–163.

27 Troilius C. Ultrasound-assisted lipoplasty: is it really safe? Aesth Plast Surg. 1999;23:307–311.