Treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

Introduction

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is common, affecting between 10% and 40% of the population of most Western countries.1,2 It is difficult to establish if the incidence of GORD is increasing but it is certainly the case that more and more patients are being treated for reflux. This is reflected in a dramatic rise in the overall cost of medical therapy for GORD in many countries over recent decades. In addition, the incidence of distal oesophageal adenocarcinoma is increasing,3 which provides circumstantial evidence that complications of gastro-oesophageal reflux, such as the development of Barrett’s oesophagus, are also increasing.

GORD is caused by excessive reflux of gastric contents, which contain acid and sometimes bile and pancreatic secretions, into the oesophageal lumen. Pathological reflux leads to heartburn, upper abdominal pain and the regurgitation of gastric contents into the oropharynx. A multifactorial aetiology is most likely. Hiatus herniation is associated with reflux in approximately half of the patients who undergo surgical treatment.4,5 This results in widening of the angle of His, effacement of the lower oesophageal sphincter and loss of the assistance of positive intra-abdominal pressure acting on the lower oesophagus. Reduced lower oesophageal sphincter pressure is also often found. In patients with normal resting lower oesophageal sphincter pressure, reflux may result from an excessive number of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation events.6 Other factors that might contribute to reflux are abnormal oesophageal peristalsis (which causes poor clearance of refluxed fluid) and delayed gastric emptying.

The treatment of reflux is incremental, commencing with medical measures, surgery being reserved for patients with more severe disease who either fail to respond adequately to medical treatment or who do not wish to take lifelong medication. In basic terms, medical therapy treats the effects of reflux, as the underlying reflux problem is not corrected, and treatment is usually continued indefinitely.7 In contrast, surgery aims to be curative, preventing reflux by reconstructing an antireflux valve at the gastro-oesophageal junction.6,8 In the past, surgery was reserved for patients with complicated reflux disease or those with very severe symptoms. However, since the introduction of laparoscopic surgical approaches some surgeons advocate utilising surgery at earlier stages in the course of reflux disease. Endoscopic (transoral) antireflux procedures have also been developed, although the outcomes following these treatments have been disappointing.

Medical treatment

H2-receptor antagonists

When first used in the 1970s, histamine type 2 (H2)-receptor antagonists, which reduce the production of gastric acid, revolutionised the medical approach to duodenal ulcer disease. However, they were less effective for reflux disease and although they sometimes relieve mild to moderate reflux symptoms, few patients achieve complete relief of symptoms.9 With the current widespread availability of proton-pump inhibitors, H2-receptor antagonists are now rarely used as first-line medical therapy.

Proton-pump inhibitors

Proton-pump inhibitors (omeprazole, lanzoprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and esomeprazole) were introduced into clinical practice in the late 1980s.7 Proton-pump inhibitors are much more effective at symptom relief and achieve better healing of oesophagitis than H2-receptor antagonists. However, in patients with severe oesophagitis (Savary Miller grade 2/3) there is a high treatment failure rate,10 and many patients who initially achieve good symptom control develop ‘breakthrough’ symptoms at a later date, requiring an increased dose of medication to maintain symptom control. Failure may be due to inadequate acid suppression, although in some cases bile or duodenal refluxate may play a role. In patients who respond well to proton-pump inhibitors, symptoms usually recur rapidly (sometimes in less than 24 hours) following cessation of medication, and for this reason lifelong medical treatment is likely to be required.7 The long-term use of proton-pump inhibitors appears generally safe. One study has shown, however, that long-term use can be associated with the development of atrophic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia in patients with concurrent Helicobacter pylori infection.11 Long-term use can also be associated with parietal cell hyperplasia.12 This latter phenomenon may be the reason why symptoms recur rapidly in some patients on cessation of therapy, and may be another reason why some patients require escalating dosages of proton-pump inhibitors to control their symptoms.

Prokinetic agents

Cisapride is the only prokinetic agent that has been shown to be better than placebo for the treatment of reflux.13 It acts by improving acid clearance from the distal oesophagus by accelerating gastric emptying. Its therapeutic benefit is similar to that of the H2-receptor antagonists. Hence, its clinical role has been limited since proton-pump inhibitors became widely available. An incidence of cardiac arrhythmias in the 1990s led to its withdrawal in most parts of the world.

Surgical treatment

Selection criteria for surgery

As a general rule, all patients who undergo antireflux surgery should have objective evidence of reflux. This may be the demonstration of erosive oesophagitis on endoscopy or an abnormal amount of acid reflux demonstrated by 24-hour pH monitoring. Neither of these tests is sufficiently reliable to base all preoperative decisions on their outcome,14 as a number of patients with troublesome reflux will have either a normal 24-hour pH study or no evidence of oesophagitis at endoscopy (and, very occasionally, both). For this reason the tests have to be interpreted in the light of the patient’s clinical presentation, and a final recommendation for surgery must be based on all available clinical and objective information.14 More recently, impedance monitoring (in combination with pH monitoring) has been used to measure ‘volume’ reflux, although the additional information obtained from this investigation appears unlikely to influence surgical decision-making.15

Patients with complicated reflux disease

Reflux with stricture formation: In the past, surgery was the only effective treatment for strictures, and when the stricture was densely fibrotic this even meant resection of the oesophagus. Fortunately, it is now unusual to see patients with such advanced strictures since proton-pump inhibitors became available, so that the role of surgery seems to have lessened.16 Strictures in young and fit patients are usually best treated by antireflux surgery and dilatation. However, many patients who develop strictures are elderly or infirm and the use of proton-pump inhibitors with dilatation is usually effective in this group.

Reflux with respiratory complications: When gastro-oesophageal regurgitation spills over into the respiratory tree, this can cause chronic respiratory illness, such as recurrent pneumonia, asthma or bronchiectasis. This is a firm indication for antireflux surgery, as the predominant action of proton-pump inhibitors is to block acid secretion and the volume of reflux is not greatly altered.

Reflux with throat symptoms: Halitosis, chronic cough, chronic laryngitis, chronic pharyngitis, chronic sinusitis and loss of enamel on teeth are sometimes attributed to gastro-oesophageal reflux. Whilst there is little doubt that on occasions such problems do arise in refluxing patients, these problems in isolation are not reliable indications for surgery. Whether or not these symptoms will be relieved following surgery is unpredictable. If symptoms are associated with typical reflux symptoms such as heartburn and/or regurgitation, then response rates of approximately 80% are reported, whereas throat symptoms in the absence of typical reflux symptoms respond poorly to surgery, with success rates of less than 50% reported.17

Columnar-lined (Barrett’s) oesophagus: Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus who have reflux symptoms should be selected for surgery on the basis of their symptoms and their response to medications, not simply because they have a columnar-lined oesophagus.18 There is some experimental evidence to suggest that continuing reflux may be deleterious in regard to malignant change in oesophageal mucosa,19 and one prospective randomised trial has suggested that antireflux surgery gives superior results to drug therapy in this patient group.19 However, proton-pump inhibitors were only introduced into the medical arm of that trial in its later years.

There is also evidence that abolition of symptoms with proton-pump inhibition does not equate to ‘normalising’ the pH profile in a patient’s oesophagus.20 Since antireflux surgery does abolish acid reflux, this may become a further reason to recommend surgery in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. However, there is only limited evidence that either surgical or medical treatment of reflux in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus consistently leads to regression of the columnar lining.21 A report by Gurski et al.22 suggested that although fundoplication is not followed by a reduction in the length of Barrett’s oesophagus, it can be followed by ‘histological’ regression. In 68% of patients in this study with low-grade dysplasia, there was regression to non-dysplastic Barrett’s mucosa. Equally, studies have shown that combining medical or surgical therapy with argon-beam plasma coagulation, photodynamic therapy or radiofrequency ablation of the columnar lining achieves complete or near complete reversion to squamous mucosa.23–25 There is no evidence to support that antireflux surgery reduces the risk of dysplastic or neoplastic progression of Barrett’s oesophagus.

Patients with uncomplicated reflux disease

Medical therapy, in the form of proton-pump inhibitors, is so effective that only a minority of patients do not get substantial or complete relief of their symptoms using these agents. Despite this, patients continue to present for antireflux surgery in large numbers for reasons already discussed. An additional factor that has emerged is the rising incidence of adenocarcinoma of the cardia associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease.3 Whether antireflux surgery is more effective than long-term proton-pump inhibition at preventing the development of columnar-lined oesophagus and subsequently carcinoma of the lower oesophagus is controversial. If duodenal fluid has a role in the pathogenesis of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus, then antireflux surgery would be preferable to acid suppression alone in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus, and of course it may also prevent the development of Barrett’s oesophagus in the first place. However, this hypothesis is not adequately tested and at present there is insufficient evidence to support a position that antireflux surgery should be performed to prevent subsequent malignant transformation.

Medical versus surgical therapy

The issue of the most appropriate treatment for gastro-oesophageal reflux disease has long been a subject of disagreement between surgeons and gastroenterologists. However, most would agree that a single management strategy is unlikely to be appropriate for all patients. Equally, there is a need for better comparative data for medical versus surgical therapy. Eight randomised trials19,27–39 have been reported that have investigated this issue, but five of these were completed or commenced before the availability of both laparoscopic antireflux surgery and proton-pump inhibitor medication. All of these trials recruited patients who had reflux symptoms that were well controlled by medical therapy. In the latter trials this entailed complete symptom control with a proton-pump inhibitor at trial commencement, thereby excluding patients with uncontrolled symptoms. Hence, the majority of patients who are currently selected for surgery were excluded from the surgical arms of these trials, i.e. patients with a poor response to a proton-pump inhibitor.

In 1992, Spechler28 reported a trial of 247 patients (predominantly men) randomised to either continuous medical therapy with an H2 blocker, medical therapy for symptoms only or an open Nissen fundoplication. Overall patient satisfaction was highest following surgery at 1 and 2 years follow-up. However, neither the surgical nor medical treatment investigated is now considered optimal. The longer-term outcomes from this study were published in 2001, with median follow-up of approximately 7 years and with proton-pump inhibitors now used for the medically treated patients.40 Follow-up was not complete and only 37 (45%) surgical patients were available for late follow-up, with 23% of the original surgical group lost to follow-up, and 32% died during follow-up. The later results did, however, show reasonable outcomes in both the medically and surgically treated groups. However, 62% of the surgical patients consumed antireflux medications at late follow-up, although when these medications were ceased in both study groups the surgical group had significantly fewer reflux symptoms than the medical group, suggesting that most of the surgical patients did not actually need the medications!

In 2003, Parrilla et al.29 reported a randomised trial that randomised 101 patients with Barrett’s oesophagus. Medical therapy was initially an H2 blocker and later a proton-pump inhibitor. A satisfactory clinical outcome was achieved at 5 years follow-up in 91% of each group, although medical treatment was associated with a poorer endoscopic outcome. Progression to dysplasia was similar in both groups.

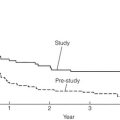

In 2000, Lundell et al.30,31,39 reported a trial of proton-pump inhibitor medication versus open antireflux surgery. Three hundred and ten patients were randomised, and antireflux surgery achieved a better outcome at up to 3 years follow-up. Later reports of 7 years follow-up in 228 patients, and 12 years follow-up in 124, confirmed that surgery still achieved better reflux control than medication, although dysphagia and various wind-related side-effects were more common after fundoplication.39,41

Rhodes et al. reported the first randomised trial to compare proton-pump inhibitor medication with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; 217 patients were enrolled. Surgery was followed by less oesophageal acid exposure 3 months after treatment and better symptom control at 12 months.32,33,42 A similar study by Anvari et al. enrolled 104 patients into a trial of proton-pump inhibitor therapy versus laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication.34–36 Follow-up at 12 months and 3 years demonstrated better control of reflux and better quality of life in the patients who underwent surgery.

In 2009, Lundell et al.37 reported the outcomes for a further multicentre randomised trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus esomeprazole proton-pump inhibitor therapy (20–40 mg per day). This trial, which was funded by the pharmaceutical company that provided the medical therapy, enrolled 554 patients and outcomes at up to 3 years have been reported. Similar success rates of approximately 90% were reported for each treatment.

Pros and cons of antireflux surgery

Disadvantages

The main disadvantage is operative morbidity (see discussion of complications). Laparoscopic surgery has greatly reduced the pain associated with open surgery; however, most patients experience some difficulty in swallowing in the immediate postoperative period, albeit temporary for the majority.43 The time taken to improve is variable, often several months.5 Furthermore, most patients experience early satiety leading to postoperative weight loss.5 In the patients who are overweight at the time of surgery (the majority!) this may be seen as an advantage. This restriction on meal size also usually disappears over a few months.

Fundoplication produces a one-way valve; thus, patients have to be forewarned that they may not be able to belch effectively after the operation, especially in the first 6–12 months after surgery, and hence they should be cautious about drinking gassy drinks.44 This applies particularly to patients who undergo a Nissen (total) fundoplication. For similar reasons, patients will be unable to vomit after an effective procedure, and should be informed of this. Failure to belch swallowed gas leads to increased passage of flatus after the procedure.45 Patients who undergo a partial fundoplication (particularly anterior) have a lower incidence of these problems.4 Despite these negative sequelae, the overwhelming majority of patients claim that the disadvantages are far outweighed by the advantages of the operation.4,43,46 To date it has not been possible to predict preoperatively those patients who will develop problems following surgery.

Preoperative investigations

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is essential. It enables oesophagitis to be documented (confirming reflux disease), strictures to be dilated, and other gastro-oesophageal pathology to be excluded, documented and treated. The position of the squamocolumnar junction and the presence and size of any hiatus hernia is also assessed. The presence of a large hiatus hernia is not a contraindication to a laparoscopic approach, although the surgery is technically more difficult.47

Oesophageal pH monitoring

While many surgeons advocate the routine assessment of patients with 24-hour ambulatory pH monitoring before antireflux surgery, we use a selective approach. This test is not sufficiently accurate to be regarded as the ‘gold standard’ for the investigation of reflux, and if an abnormal pH profile is used to select patients for surgery, up to 20% of patients who have oesophagitis and typical reflux symptoms will be excluded unnecessarily from antireflux surgery. Hence, we apply this investigation in patients with endoscopy-negative reflux disease and in patients with atypical symptoms.14 This test’s ability to clarify whether symptoms are associated with reflux events is useful.

Other investigations

The role of bile reflux monitoring remains undefined in gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, although it has been suggested that it may be helpful in patients who fail to respond to acid suppression. This is measured using either ‘Bilitec’ or multichannel intraluminal impedance (MII) monitoring. ‘Bilitec’ measures intra-oesophageal bilirubin as an indirect marker of duodeno-oesophageal reflux, but has largely been superseded by MII, which measures ‘volume’ reflux. However, at this time, MII has only a limited role in the selection of patients for surgery.15

Antireflux surgery

Mechanisms of action of antireflux surgery

Total fundoplications, such as the Nissen, or partial fundoplications, whether anterior or posterior, probably all work in a similar fashion.8,57 The mechanisms of action of an antireflux operation are not completely clear; they may work as much in a mechanical as physiological fashion, as these procedures are effective not only when placed in the chest in vivo,58 but also on the benchtop, i.e. ex vivo.8 Some of the proposed mechanisms include:

1. The creation of a floppy valve by maintaining close apposition between the abdominal oesophagus and the gastric fundus. As intragastric pressure rises the intra-abdominal oesophagus is compressed by the adjacent fundus.

2. Exaggeration of the flap valve at the angle of His.

3. Increase in the basal pressure generated by the lower oesophageal sphincter.

4. Reduction in the triggering of transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxations.

5. Reduction in the capacity of the gastric fundus, thereby speeding proximal and total gastric emptying.

6. Prevention of effacement of the lower oesophagus (which effectively weakens the lower sphincter).

Since the procedures seem to work, even ex vivo,8 it seems likely that the first two mechanisms account for the efficacy of the majority of antireflux procedures. Equally, the increase in lower oesophageal sphincter pressure following surgery is not important, and in some partial fundoplication procedures there is very little increase in pressure, yet reflux is well controlled.4,59 The trend towards increasingly looser and shorter total fundoplications or greater use of partial fundoplication procedures suggests that there is no such thing as a fundoplication that is ‘too loose’.

Techniques of antireflux surgery

As ever, when there are a variety of different operations performed for the same underlying condition, this denotes that no single procedure yields perfect results, i.e. 100% reflux control with minimal side-effects. All techniques have their advocates. Published reports can be found that support every known procedure, and it is probably better to consider results from randomised trials when assessing the merits of these procedural variants (see below) rather than relying on uncontrolled outcomes reported by advocates of a single procedure. Equally, the experience of the operating surgeon is of great importance for achieving a good postoperative outcome.60 Variability can be reduced, but not eliminated, by detailed technical descriptions and effective surgical training. Over the last 20 years, a minimally invasive laparoscopic approach has become standard for primary antireflux surgery, making surgery more acceptable to patients and their physicians.

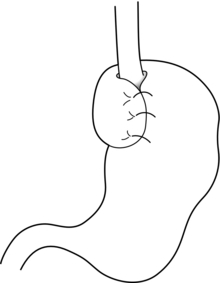

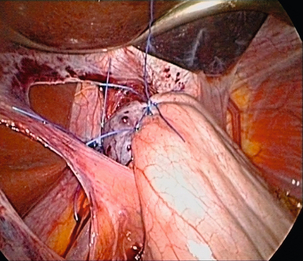

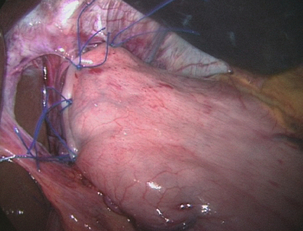

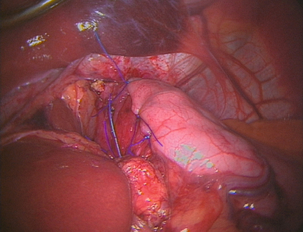

Nissen fundoplication (Figs 13.1 and 13.2): Nissen originally described a procedure that entailed mobilisation of the oesophagus from the diaphragmatic hiatus, reduction of any hiatus hernia into the abdominal cavity, preservation of the vagus nerves and mobilisation of the posterior gastric fundus around behind the oesophagus, without dividing the short gastric vessels, and suturing of the posterior fundus to the anterior wall of the fundus using non-absorbable sutures, thereby achieving a complete wrap of stomach around the intra-abdominal oesophagus.61 The original fundoplication was 5 cm in length and an oesophageal bougie was not used to calibrate the wrap. This is now the commonest antireflux operation performed worldwide.

Controversy still exists about the need to divide the short gastric vessels to achieve full fundal mobilisation. The so-called floppy Nissen procedure described by Donahue and Bombeck64 relies on extensive fundal mobilisation. On the other hand, the modification of the Nissen fundoplication using the anterior fundal wall alone, also first described by Nissen and Rossetti,61,65 does not require short gastric vessel division to construct the fundoplication. This simplifies the dissection, although more judgment and experience may be required to select the correct piece of stomach to use for the construction of a sufficiently loose fundoplication. Both procedures have their advocates, and good results (90% good or excellent long-term outcome) have been reported for both variants.62,65 Nevertheless, strong opinions are held about whether the short gastric vessels should be divided or not, and this controversy has been heightened by the introduction of laparoscopic fundoplication.

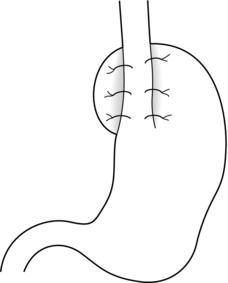

Posterior partial fundoplication (Fig. 13.3): A variety of fundoplication operations have been described in which the fundus is wrapped partially round the back of the oesophagus, with the aim of reduction of the possible side-effects of total fundoplication due to overcompetence of the cardia, i.e. dysphagia and gas-related problems. Toupet described a posterior partial fundoplication in which the fundus is passed behind the oesophagus and sutured to the left lateral and right lateral walls of the oesophagus, as well as to the right diaphragmatic pillar, creating a 270° posterior fundoplication.66 A very similar procedure was described by Lind et al.67 This entails a 300° posterior fundoplication, which is constructed by suturing the fundus to the oesophagus at the left and right lateral positions, and additionally anteriorly on the left, leaving a 60° arc of oesophageal wall uncovered. The hiatus is repaired if necessary.

Anterior partial fundoplication: Several anterior partial fundoplication procedures have been described, and all purport to reduce the incidence of dysphagia and other side-effects. The Belsey Mark IV procedure, popular in thoracic practice up the early 1990s, entails a 240° anterior partial fundoplication that is usually performed through a left thoracotomy approach.68 The distal oesophagus is mobilised, sutured to the gastric fundus and sutured to the diaphragm. Any hiatus hernia is repaired, and the anterior two-thirds of the abdominal oesophagus is covered by the fundoplication. The open thoracic access required is associated with significant morbidity, and for this reason it has fallen from favour since the arrival of laparoscopic antireflux surgery. A minimally invasive thoracoscopic approach was described 15 years ago,69 although clinical outcomes have never been reported, and this procedure is rarely performed.

The Dor procedure is an anterior hemifundoplication that involves suturing of the fundus to the left and right sides of the oesophagus.70 The Dor procedure is commonly used in combination with an abdominal cardiomyotomy for achalasia as it is unlikely to cause dysphagia, and it may reduce the risk of gastro-oesophageal reflux following cardiomyotomy.

A 120° anterior fundoplication has also been described.59 This entails reduction of any hiatus hernia, posterior hiatal repair, suture of the posterior oesophagus to the hiatal pillars posteriorly, suture of the fundus to the diaphragm to accentuate the angle of His, and creation of an anterior partial fundoplication by suturing the fundus to the oesophagus on the right anterolateral aspect. Satisfactory medium-term reflux control following open surgery has been reported for this procedure, and a low incidence of gas-related problems. However, published laparoscopic experience is more limited.

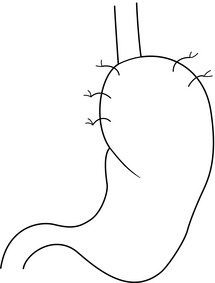

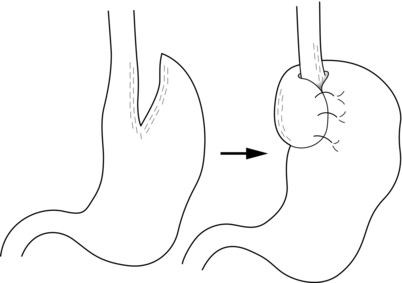

We have reported the results from prospective randomised trials of laparoscopic anterior 180° partial fundoplication and laparoscopic anterior 90° partial fundoplication versus a Nissen procedure4,71–75 (see below). The anterior 180° fundoplication procedure entails hiatal repair, suture of the distal oesophagus to the hiatus posteriorly, and construction of an anterior fundoplication that is sutured to the oesophagus and the hiatal rim on the right and anteriorly (Figs 13.4 and 13.5). The anterior 90° partial fundoplication procedure entails hiatal repair, posterior oesophagopexy, narrowing of the angle of His and construction of a limited anterior fundoplication that covers the left anterolateral aspect of the oesophagus (Fig. 13.6). These variants of anterior fundoplication show promise.

Other antireflux procedures

Hill procedure: Hill described a procedure that is often regarded as a gastropexy rather than a fundoplication.76 However, it also plicates the cardia and when examined endoscopically the intragastric appearances are similar to a fundoplication. The procedure entails suturing the anterior and posterior phreno-oesophageal bundles to the pre-aortic fascia and the median arcuate ligament. Whilst excellent results have been reported by Hill and colleagues,77 it has not been applied widely because most surgeons have difficulty understanding the anatomical principles and, in particular, the phreno-oesophageal bundles are not clear structures. Hill also emphasises the need for intraoperative manometry. This is not widely available, limiting the dissemination of his technique.

Collis procedure (Fig. 13.7): The Collis procedure is useful for patients whose oesophagogastric junction cannot be reduced below the diaphragm.78 However, this situation is very rare in current practice. The Collis procedure entails the construction of a tube of gastric lesser curve to recreate an abdominal length of oesophagus, around which a fundoplication can then be constructed to help with oesophageal shortening. It is often constructed by using a circular end-to-end stapler to create a transgastric window; a linear cutting stapler is used from this hole up to the angle of His to construct the neo-oesophagus. Laparoscopic and thoracoscopic techniques for this procedure have been described, although longer-term outcomes are not available.79,80 A disadvantage of this procedure is that the gastric tube does not have peristaltic activity and furthermore it can secrete acid. This leads to a poorer overall success rate for this procedure, although some of this could be due to the end-stage nature of the reflux disease that led to the choice of this procedure in the first place.

Augmentation of the lower oesophageal sphincter:

LINX®: In 2010, Bonavina et al.81 described a new approach to surgery for gastro-oesophageal reflux that entailed augmentation of the lower oesophageal sphincter with an implantable string of interlinked titanium beads with magnetic cores. This device (LINX Reflux Management System, Torax Medical, Shoreview, MN) is placed laparoscopically around the gastro-oesophageal junction, and aims to control reflux, but still allow normal swallowing and belching. Experience is limited to a case series of 44 patients followed for up to 2 years.81 A success rate of approximately 90%, as measured by both clinical scores and pH monitoring, has been reported, and this appears similar to the success rate following fundoplication. It is easy to place, so the potential benefits in comparison to standard Nissen are a standard approach and the relative lack of hiatal dissection. Clinicians familiar with the Angelchik prosthesis will be wary of placing a foreign body around the distal oesophagus, although placement appears to be safe. The outcomes of larger series and longer-term randomised comparative trials are required to prove clinical and cost-effectiveness before this procedures enters wide clinical practice.82

EndoStim®: Based on the premise of a dysfunctional sphincter, an innovative new approach to the management of GORD uses an implantable system to deliver electrical stimulation to the lower oesophageal sphincter in order to normalise its function and prevent acid reflux. The EndoStim® device is commercially available in the UK (CE-mark approved). A laparoscopic technique is used to implant the system’s electrodes into the distal oesophageal muscle layers using minimal hiatal dissection. A wirelessly programmable pacemaker is then placed subcutaneously. It is thought that the avoidance of a ‘wrap’ will reduce the negative sequelae associated with various fundoplications. Also, the electrical stimulation is ‘tailored’ to the individual patient’s GORD profile in terms of the number and timing of impulses. Initial data are promising when placed in patients at least partially responsive to proton-pump inhibition, with hiatal hernia ≤ 3 cm and only mild to moderate oesophagitis. Most importantly, implantation and electrical stimulation were safe. However, a well-designed, randomised, sham-control trial is needed to validate this approach.83

Controversies and comparisons

Complete or partial fundoplication?

Many prospective randomised trials of Nissen versus a partial fundoplication have been performed. DeMeester et al.84 had the distinction of reporting the first randomised study in the field of surgery for reflux disease in 1974. Their trial randomised 45 patients to undergo either a Nissen, Hill or Belsey procedure, and they followed up their patients for 6 months after surgery. The dysphagia and recurrent reflux rates were similar for all three procedures. However, the number of patients was too small to allow a meaningful comparison to be made.

Nissen versus posterior fundoplication

Eleven randomised trials have compared a Nissen with a posterior partial fundoplication. Some of the trials contribute little to the pool of evidence as they are either small and underpowered, or only reported very-short-term outcomes.53,85–88

Lundell et al.89 reported the outcomes of the first large trial of Nissen versus a posterior (Toupet) partial fundoplication; 137 patients were enrolled. The early outcomes at 6 months follow-up were similar. At 5 years follow-up90 reflux control and dysphagia rates were also similar, although flatulence was commoner after Nissen fundoplication at 2 and 3 years but not at 4 or 5 years follow-up. Re-operation was more common following Nissen fundoplication, with one patient in the posterior fundoplication group undergoing further surgery for severe gas bloat symptoms and five of the Nissen group undergoing re-operation for postoperative paraoesophageal herniation. A reanalysis of the data from this trial45 sought to answer the question of whether a tailored approach to antireflux surgery should be applied. There were no demonstrable disadvantages for the Nissen procedure in those patients who had manometrically abnormal peristalsis before surgery. In 2011, minimum follow-up of 18 years was reported.91 The outcomes at this very late follow-up were equivalent, with success rates of more than 80% reported for both procedures, and no significant differences in the incidence of side-effects at late follow-up, suggesting that the mechanical side-effects following Nissen fundoplication improve progressively with very-long-term follow-up.

Zornig et al.92 reported a trial that enrolled 200 patients to either total fundoplication with division of the short gastric vessels or posterior fundoplication. One hundred patients had normal preoperative oesophageal motility and 100 had ‘abnormal’ motility. At 4 months follow-up an overall good outcome was obtained in about 90% of patients in each group, and reflux control was equivalent. Short-term dysphagia was less common following posterior partial fundoplication, and no correlation was seen between preoperative oesophageal motility and outcome, providing no support for the selective application of a partial fundoplication in patients with abnormal preoperative motility. The 2-year follow-up outcomes were similar.55 Eighty-five per cent of each group were satisfied with their clinical outcome, and dysphagia remained significantly more common after Nissen fundoplication (19 vs. 8 patients).

A study by Guérin et al.93 enrolled 140 patients. At 3 years follow-up 118 patients were evaluated and no outcome differences could be identified. Similarly, Booth et al.54 enrolled 127 patients in a trial of Nissen versus Toupet fundoplication, Khan et al.94 enrolled 121 patients in another trial, and Shaw et al.95 enrolled 100. Each of these trials showed no differences in reflux control 1 year after surgery. Although dysphagia was more common following Nissen fundoplication in Booth et al.’s trial, there were no differences in the prevalence of side-effects in the other trials. Subgroup analysis in Booth et al.’s and Shaw et al.’s trials did not reveal any differences between patients with or without poor preoperative oesophageal motility.

Nissen versus anterior fundoplication

Six trials have evaluated Nissen versus anterior partial fundoplication. In 1999 we reported the first prospective randomised trial to compare a Nissen fundoplication with an anterior partial fundoplication technique.4 Both procedures were performed laparoscopically. This study enrolled 107 patients to undergo either a Nissen or anterior partial fundoplication. The partial fundoplication variant entailed a 180° fundoplication that was anchored to the right hiatal pillar and the oesophageal wall (Figs 13.4 and 13.5). Whilst no overall outcome differences between the two procedures were demonstrated at 1 and 3 months follow-up, at 6 months patients who underwent an anterior fundoplication were less likely to experience dysphagia for solid food, were less likely to be troubled by excessive passage of flatus, were more likely to be able to belch normally, and the overall outcome was better. The outcomes at 5 years confirmed the results of the initial report.71 Reflux control was slightly better after Nissen fundoplication, but this was offset by significantly less dysphagia, less abdominal bloating and better preservation of belching, resulting in a greater proportion of patients reporting a good or excellent overall outcome 5 years after anterior fundoplication (94% vs. 86%). At 10 years follow-up, however, there were no significant outcome differences for the two procedures, with equivalent control of reflux, and no differences for side-effects,74 a similar outcome to the very late follow-up for the Lundell and colleagues, trial of Nissen versus posterior partial fundoplication.91

Baigrie et al.96 reported 2-year follow-up from a similar study in which 161 patients underwent either a Nissen or anterior 180° partial fundoplication. This trial demonstrated equivalent control of reflux symptoms and less dysphagia following anterior 180° partial fundoplication, although the incidence of re-operation for recurrent reflux was higher after anterior fundoplication. Cao et al.97 reported 5-year outcomes for a similar trial that enrolled 100 patients. Reflux control was similar for the two procedures, and flatulence was less common after anterior 180° partial fundoplication. Raue et al.98 reported equivalent outcomes at 18 months mean follow-up in a smaller trial that enrolled 64 patients.

Two further trials have compared a laparoscopic anterior 90° partial fundoplication with a Nissen fundoplication. In the first of these, 112 patients were enrolled in a multicentre randomised trial conducted in six cities in Australia and New Zealand.72,75 Side-effects were significantly less common following anterior 90° fundoplication, although this was offset by a slightly higher incidence of recurrent reflux at 6 months follow-up.72 At 5 years the outcomes were similar for side-effects, although reflux was worse after the partial fundoplication.75 Satisfaction with the overall outcome was similar for both fundoplication types. Similar outcomes were reported from a parallel single-centre randomised trial that enrolled 79 patients – fewer side-effects offset by more reflux.73

Anterior versus posterior partial fundoplication

Two randomised trials have directly compared anterior versus posterior partial fundoplication. Hagedorn et al.99–101 randomised 95 patients to undergo either a laparoscopic posterior (Toupet) or anterior 120° partial fundoplication. Their results showed better reflux control, but more side-effects following posterior partial fundoplication. Unfortunately, the clinical and objective outcomes following anterior 120° fundoplication in this trial were much worse than the outcomes from other randomised and non- randomised studies. The average exposure time to acid (pH < 4) was 5.6% following anterior fundoplication in their study, whereas in other studies this figure is reported to be between 2.5% and 2.7%,4,72 suggesting that the procedure performed in the study of Hagedorn et al. was less effective and therefore different to the procedures performed in other studies. More recently, Khan et al.102 reported 6 months follow-up from a trial that enrolled 103 patients to undergo anterior 180° versus posterior partial fundoplication. Reflux control was also better after posterior partial fundoplication, but offset by more side-effects.

Division/no division of short gastric vessels

Until the 1990s the issue of division versus non-division of the short gastric vessels was rarely discussed. However, following anecdotal reports of increased problems with postoperative dysphagia following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication without division of the short gastric vessels,104,105 this aspect of surgical technique became a much debated topic. Routine division of the short gastric vessels during fundoplication, to achieve full fundal mobilisation and thereby ensure a loose fundoplication, is thought by some to be an essential step during laparoscopic (and open) Nissen fundoplication.62 This opinion was popularised by the publication of studies that compared experience with division of the short gastric vessels with historical experience with a Nissen fundoplication performed without dividing these vessels.62,64,104,105 However, other uncontrolled studies of Nissen fundoplication either with or without division of the short gastric vessels confuse the issue further, as good results have been reported whether these vessels were divided or not.62,65

Six randomised trials have been reported that investigate this aspect of technique. Luostarinen et al.106,107 reported the outcome of a small trial of division versus no division of the short gastric vessels during open total fundoplication. Fifty patients were entered into this trial and a later report107 described outcomes following median 3-year follow-up. Both procedures effectively corrected endoscopic oesophagitis. However, there was a trend towards a higher incidence of disruption of the fundoplication (5 vs. 2) and reflux symptoms (6 vs. 1) in patients whose short gastric vessels were divided, and 9 of 26 patients who underwent vessel division developed a postoperative sliding hiatus hernia, compared to only 1 of 24 patients whose vessels were kept intact. The likelihood of long-term dysphagia or gas-related symptoms was not influenced by mobilising the gastric fundus in this trial.

In 1997 we reported a randomised trial that enrolled 102 patients undergoing a laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication to have a procedure either with or without division of the short gastric vessels.5 No difference in overall outcome was demonstrated at initial follow-up of 6 months and the trial failed to show that dividing the short gastric vessels during laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication reduced the incidence or severity of early postoperative dysphagia, or the outcome of any objective investigations. At 5 and 10 years follow-up,108,109 both procedures were equally durable in terms of reflux control and the incidence of postoperative dysphagia. At 5 years follow-up division of the short gastric vessels was associated, with more flatulence and bloating, and greater difficulties with belching.

Blomqvist et al.110,111 reported the outcome of a similar trial that enrolled 99 patients. At 12 months and 10 years follow-up, this study also showed that dividing the short gastric vessels did not improve the outcome. A recent meta-analysis of larger data with 12 years follow-up, generated by combining the raw Adelaide and Swedish data, confirmed equivalent reflux control, but more bloating after division of the short gastric vessels.112

Farah et al.,113 Kösek et al.114 and Chrysos et al.115 all reported trials that showed equivalent reflux control and postoperative dysphagia irrespective of whether the short gastric vessels were divided or not. However, as with the Adelaide and Swedish data, they also demonstrated an increased incidence of bloating symptoms after division of the short gastric vessels.

Laparoscopic antireflux surgery

Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication was first reported in 1991116,117 and rapidly established itself as the procedure of choice for reflux disease, with the vast majority of antireflux procedures now performed this way. The results of several large series with long-term clinical follow-up have now been published.118,119 These confirm that laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is effective, and that 10 years after surgery it achieves an excellent clinical outcome in more than 85–90% of patients. Furthermore, with even longer follow-up, it is likely that this procedure will be as durable as open fundoplication, where a 70–80% success rate can be expected at up to 25 years follow-up.120

However, several complications unique to the laparoscopic approach have been described (see below). Dysphagia could be more common following laparoscopic fundoplication, although this may be due to the more intense nature of the prospective follow-up applied in many centres. Furthermore, in our experience dysphagia has been less of a problem after fundoplication than it was before surgery, with a reduction in the incidence from approximately 30% before surgery to less than 10% at 12 months following surgery,4,5 and for the majority of these patients dysphagia has not been troublesome in the long term.

Up to 10% of patients are dissatisfied. Some of this dissatisfaction is because of a complication of the original surgery. In our experience this has usually been either the development of a paraoesophageal hernia or because of continuing troublesome dysphagia (with either the wrap or the hiatus being too tight). Some patients are dissatisfied, however, even though their reflux has been cured and they have not had any complications.121 This is usually because they do not like the flatulence that can follow the procedure. It is also important to recognise that there is a learning curve associated with this form of surgery, and we have demonstrated that the first 20 patients in an individual surgeon’s experience are associated with a higher complication rate, and as experience increases the re-operation rates fall to below 5%.60 There are no specific contraindications to the laparoscopic approach, and the repair of giant hiatal hernias and re-operative antireflux surgery are both feasible (although technically more demanding).

Laparoscopic versus open antireflux surgery

Non-randomised comparisons between open and laparoscopic fundoplication generally showed that laparoscopic surgery required more operating time than the equivalent open surgical procedure,122,123 that the incidence of postoperative complications was reduced, the length of postoperative hospital stay was shortened by 3–7 days, patients returned to full physical function 6–27 days quicker, and overall hospital costs were reduced. The efficacy of reflux control appeared to be similar between the two approaches. Ten randomised controlled trials have been reported that compare a laparoscopic fundoplication with its open surgical equivalent.124–138 Nine of these investigated a Nissen fundoplication and one study compared laparoscopic versus open posterior partial fundoplication.132 The early reports that described follow-up extending up to 12 months confirmed advantages for the laparoscopic approach, albeit less dramatic than the advantages expected from the results of non-randomised studies. More recently, longer-term outcomes from some studies have been reported.133,135,137,139,140

Early reports from smaller trials125–127 that each enrolled 20–42 patients demonstrated equivalent short-term clinical outcomes, shortening of the postoperative stay by about 1 day (3 vs. 4 median), longer operating times (extended by approximately 30 minutes), and an overall reduction in the incidence of postoperative complications following laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. The reduction in the length of the postoperative hospital stay by only 1 day was unexpected. This was achieved entirely by a shorter hospital stay following open fundoplication, suggesting that at least some of the apparent benefits of the laparoscopic approach have been due to a general change in management policy to encourage earlier oral intake, avoiding nasogastric tubes and encouraging earlier discharge from hospital.

Chrysos et al.128 reported 12 months follow-up for a trial that enrolled 106 patients. Both approaches achieved effective reflux control, post-fundoplication dysphagia was similar, and the laparoscopic approach was followed by fewer complications, a quicker recovery and fewer symptoms of epigastric bloating and distension. Similar 12-month postoperative outcomes were demonstrated by Ackroyd et al.138 in a trial that enrolled 99 patients.

Håkanson et al.132 enrolled 192 patients into a trial of laparoscopic versus open posterior partial fundoplication. Their results were similar to the trials of laparoscopic versus open Nissen fundoplication. Early complications were more common after open surgery, the length of the hospital stay was longer (5 vs. 3 days) and return to work was slower (42 vs. 28 days). However, this was offset by a higher incidence of early side-effects and recurrent reflux in the laparoscopic group. At 3 years follow-up, however, there were no outcome differences, satisfaction with the surgery was similar for the two groups, and the need for re-operative surgery of any sort was not influenced by the choice of technique.

Laine et al.124 reported 110 patients randomised to undergo laparoscopic or open Nissen fundoplication. As with the other trials, hospital stay was shorter, being halved from 6.4 to 3.2 days and patients returned to work quicker (37 vs. 15 days), but operating time was also prolonged by 31 minutes. Subsequent reports from this group137,140 described 11- and then 15-year follow-up in 86 patients. Whilst symptom control and side-effects were similar at late follow-up and 82% of the laparoscopic surgery group were satisfied with the late outcome, the incidence of wrap disruption at endoscopic assessment was significantly higher following open surgery (40% vs. 13%) and there were 10 incisional hernias, all following the open technique. Similar outcomes were reported by Nilsson et al.136 in a smaller trial that followed patients for 5 years.

The study that created the most controversy in this area was published by Bais et al. in 2000.129 This multicentre study initially enrolled 103 patients. The early (3 months) results of this trial showed a disadvantage for the laparoscopic approach and the trial was stopped early because of an excess of adverse end-points. The investigators were criticised for terminating the trial prematurely,141,142 as it can be argued that the conclusions were misleading. The decision to stop the trial was based primarily on postoperative dysphagia within the first 3 months. Other studies have reported that most patients who undergo a Nissen fundoplication still have some dysphagia 3 months after surgery,5,130 but that this dysphagia usually subsides as time passes. Hence, a follow-up period of 3 months is too short for the end-point of dysphagia to be adequately assessed. Subsequent reports of 5- and 10-year follow-up from this trial133,139 confirmed the validity of this critique. With further enrolment boosting the number of patients to 177, no differences in symptoms or subjective outcome could be demonstrated at late follow-up. In addition, 24-hour pH monitoring confirmed equivalent reflux control. At 10-year follow-up, there was a higher rate of surgical reintervention following open surgery, mainly due to an excess of incisional hernias. Hence, the late results of this trial actually support the application of laparoscopic antireflux surgery.

Complications of laparoscopic antireflux surgery

As experience with laparoscopic approaches for antireflux surgery became standard practice, complications unique to the laparoscopic approach emerged (Box 13.1). These include postoperative paraoesophageal hiatus hernia, re-operation for dysphagia, and gastrointestinal perforation. Nevertheless, the risk of complications should be balanced against the advantages of the laparoscopic approach, as the overall complication rate is reduced following laparoscopic surgery.139 The likelihood of complications can be influenced by a number of factors, including surgeon experience and expertise, operative technique and perioperative care. Furthermore, the final outcome of some complications can be moderated significantly by applying appropriate early management strategies.

Complications that are more common following laparoscopic antireflux surgery

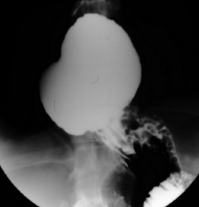

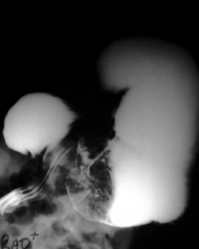

Paraoesophageal hiatus hernia: Paraoesophageal hiatus herniation was thought to be an uncommon finding following open fundoplication, presenting usually in the late follow-up period, although its frequency was probably underestimated in the past. Most large series of laparoscopic procedures report the occurrence of paraoesophageal herniation following surgery (Fig. 13.8), particularly in the immediate postoperative period.63,148,158 The incidence of this complication ranges up to 7% in published reports,63 and it seems that this is exacerbated by some factors inherent in the laparoscopic approach. These include a tendency to extend laparoscopic oesophageal dissection further into the thorax than during open surgery, an increased risk of breaching the left pleural membrane143 and the effect of reduced postoperative pain. Loss of the left pleural barrier can allow the stomach to slide more easily into the left hemithorax, and less pain permits more abdominal force to be transmitted to the hiatal area during coughing, vomiting or other forms of exertion in the initial postoperative period, pushing the stomach into the thorax, as the normal anatomical barriers have been disrupted by surgical dissection. Early resumption of heavy physical work has also been associated with acute herniation. Strategies are available that can reduce the likelihood of herniation. Routine hiatal repair has been shown to reduce the incidence by approximately 80%.63 In addition, excessive strain on the hiatal repair during the early postoperative period should be avoided by the routine use of antiemetics, and advising patients to avoid excessive lifting or straining for about 1 month following surgery.

Dysphagia: The debate in the laparoscopic era is whether dysphagia is more likely to occur following laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Nearly all patients, including those who undergo a partial fundoplication, experience dysphagia requiring dietary modification in the first weeks to months following laparoscopic surgery. However, it is dysphagia that is severe enough to need further surgery that is of most concern. Early severe dysphagia requiring surgical revision has been reported in a number of series.149,159,160 Conversion of a Nissen fundoplication to a partial fundoplication has been performed for troublesome dysphagia following both open and laparoscopic techniques, usually with success.160,161

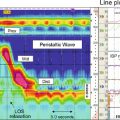

More common with the laparoscopic approach, however, is the problem of a tight oesophageal diaphragmatic hiatus causing dysphagia149,161 (Figs 13.9 and 13.10). Two factors may cause this problem: over-tightening of the hiatus during hiatal repair and excessive perihiatal scar tissue formation. Many surgeons use an intra-oesophageal bougie to distend the oesophagus, to assist with calibration of the hiatal closure. However, this will not always prevent over-tightening from occurring. If a problem does arise in the immediate postoperative period, it can usually be corrected by early laparoscopic reintervention with release of one or more hiatal sutures. Later narrowing of the oesophageal hiatus due to postoperative scar tissue formation in the second and third postoperative weeks, even in patients not undergoing initial hiatal repair, has also been described. In our experience, endoscopic dilatation with standard bougies usually only provides temporary relief of symptoms rather than a long-term solution. Correction of this problem often requires widening of the diaphragmatic hiatus. This can be achieved by a laparoscopic approach, with anterolateral division of the hiatal ring and adjacent diaphragm until the hiatus is sufficiently loose. An alternative strategy, which is sometimes successful, is pneumatic balloon dilatation (using a 30-mm-diameter balloon).

Pulmonary embolism: Pulmonary embolism was more common in some of the early reports of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication145 and in particular following conversion of cases to open surgery, suggesting that prolonged operating times might be an important aetiological factor. In addition, several mechanical factors inherent in the laparoscopic antireflux surgery environment create a scenario in which venous thrombosis is more likely. The combination of head-up tilt of the operating table, intra-abdominal insufflation of gas under pressure and elevation of the legs in stirrups greatly reduces venous flow in the leg veins, potentially predisposing patients to deep venous thrombosis. This problem can be minimised by the routine use of vigorous antithromboembolism prophylaxis, including low-dose heparin, antiembolism stockings and mechanical compression of the calves.

Complications unique to laparoscopic antireflux surgery

Bilobed stomach: A technical error described during early experiences with laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication is the ‘bilobed stomach’.145 This occurs when too distal a piece of stomach is used to form the Nissen fundoplication wrap, usually the gastric body rather than the fundus, resulting in a bilobular-shaped stomach (Fig. 13.11). Most patients are asymptomatic; in extreme cases it is possible for the upper part of the stomach to become obstructed at the point of constriction in the gastric body, resulting in postprandial abdominal pain, which requires surgical revision (Fig. 13.12). Checking carefully to ensure that the correct piece of stomach (the fundus) is used for construction of the fundoplication prevents this problem from arising.

Pneumothorax: Intraoperative pneumothorax occurs in up to 2% of patients due to injury to the left pleural membrane during retro-oesophageal dissection, particularly if dissection is directed too high within the mediastinum.143 This is more likely to occur during dissection of a large hiatus hernia. Careful dissection behind the oesophagus, ensuring that the tips of instruments passed from right to left behind the oesophagus do not pass above the level of the diaphragm, and experience with laparoscopic dissection at the hiatus reduce its likelihood. The occurrence of a pneumothorax does not usually require the placement of a chest drain, as CO2 gas in the pleural cavity is rapidly reabsorbed at the completion of the procedure, allowing the lung to re-expand rapidly.

Vascular injury: Vascular injury to the inferior vena cava, the left hepatic vein and the abdominal aorta have all been reported.147,162 This problem may be associated with aberrant anatomy, inexperience, the excessive use of monopolar diathermy cautery dissection, the incorrect application of ultrasonic shears, or a combination of these. Intraoperative bleeding more commonly follows inadvertent laceration of the left lobe of the liver by the liver retractor or other instrument and haemorrhage from poorly secured short gastric vessels during fundal mobilisation. A rare complication is cardiac tamponade, which has been reported twice,156,163 once due to laceration of the right ventricle by a liver retractor and once due to an injury of the cardiac wall from a suture needle. The proximity of the heart, inferior vena cava and aorta to the distal oesophagus renders potentially life-threatening injuries a possibility if surgeons are unfamiliar with the laparoscopic view of hiatal anatomy. Nevertheless, the risk of perioperative haemorrhage during and after antireflux surgery is probably reduced by a laparoscopic approach, as is the likelihood of splenectomy.

Perforation of the upper gastrointestinal tract: Oesophageal and gastric perforation are specific risks, with an incidence of approximately 1%.45,155 Gastric perforation of the cardia can result from excessive traction by the surgical assistant. Perforation of the back wall of the oesophagus usually occurs during dissection of the posterior oesophagus. The anterior oesophageal wall is probably at greatest risk when a bougie is passed to calibrate the fundoplication or the oesophageal hiatus. All these injuries can be repaired by suturing either laparoscopically or by an open technique. Awareness that injury can occur enables surgeons to institute strategies that reduce the likelihood of their occurrence. Furthermore, injury is less likely with greater experience.

Mortality

Deaths have been reported following laparoscopic antireflux procedures. Causes include peritonitis secondary to duodenal perforation,155 thrombosis of the superior mesenteric artery and the coeliac axis,150 and infarction of the liver.164 However, the overall mortality of laparoscopic antireflux surgery is probably less than 0.1%.

Avoiding complications following laparoscopic antireflux surgery and minimising their impact

To avoid or minimise complications following a laparoscopic antireflux procedure, a range of strategies should be considered and applied whenever possible. Most agree that the oesophageal hiatus should be narrowed or reinforced with sutures, irrespective of whether a hiatus hernia is present or not.63 A barium swallow examination on the first or second postoperative day should be used to confirm that the fundoplication is in the correct position and that the stomach is entirely intra-abdominal. If there is any uncertainty endoscopic examination may clarify the situation. If the appearances are not acceptable, or if other problems such as severe dysphagia or excessive pain occur, then re-exploration should be performed, as early laparoscopic reintervention is associated with minimal morbidity and usually delays the patient’s recovery by only a few days. Most complications requiring reintervention can be readily dealt with laparoscopically within a week of the original procedure.43 Beyond this time, however, laparoscopic re-operation becomes difficult, and for this reason we have a relatively low threshold for laparoscopic re-exploration in the first postoperative week if early problems arise.

If complications become apparent at a later stage, laparoscopic re-operation may still be feasible if an experienced surgeon is available.161 However, the likelihood of success is reduced in the intermediate period following the original procedure, and in this case waiting until scar tissue has matured (i.e. at least 3–6 months) simplifies subsequent dissection and increases the likelihood of completing the procedure laparoscopically.

Synthesis of the results from prospective randomised trials

The results of randomised trials can be assessed together to facilitate the development of guidelines for antireflux surgery (Box 13.2). Some of these will meet with wide acceptance as they support the current body of thought of the international surgical community. However, others are controversial, as they do not support the opinions of the majority of experts in the field.

Endoscopic therapies for reflux

Over the last decade, endoscopic procedures for the treatment of reflux have emerged as they offer the potential for reflux control without abdominal wall incisions These approaches appeal to patients and physicians and can be broadly categorised into four types (Box 13.3). Three of these approaches aim to narrow the gastro-oesophageal junction by using radiofrequency energy,165 injection of an inert substance166 or endoscopic suturing.167 Since the early 2000s these procedures have been applied with enthusiasm, particularly in the USA. However, none of these treatments apply the established principles that underpin the efficacy of antireflux surgery (see ‘Mechanism of action of antireflux operations’ section above) and the clinical outcomes were all predictably disappointing.168 More recently, however, a fourth technique has been described that constructs an anterior partial fundoplication using a totally endoscopic (transoral) technique.169 Because the latter approaches aim to fix the fundus of the stomach to a length of intra-abdominal oesophagus, first principles suggest that these approaches should be more successful, although the clinical reality has also been disappointing.

Radiofrequency

The Stretta procedure165 used a purpose-built device to apply radiofrequency energy to the muscular layer of the oesophageal wall at the gastro-oeosophageal junction. The device comprised a 30-mm-diameter balloon, four 5.5-mm-long retractable stylet electrodes and a mucosal irrigation system. It was passed over an endoscopically placed guidewire and positioned at the gastro-oesophageal junction. The electrodes were deployed to puncture the oesophageal wall, and radiofrequency energy was applied to cauterise the oesophageal muscle. The Stretta procedure generated fibrosis in the muscle layer with the aim of tightening the gastro-oesophageal junction. In general, patients were only selected for this treatment if they had mild grades of reflux. Whilst short-term follow-up of case series suggested reduced reflux symptoms and reduced oesophageal acid exposure, the magnitude of the reduction in acid exposure was disappointing, and most patients continued to have abnormal reflux after treatment.170 A randomised trial that compared the Stretta procedure with a sham endoscopy showed no differences at 6 months follow-up.171 The trial demonstrated a large placebo effect in the sham controls, and this should be remembered when considering the outcomes of any antireflux therapy. The company that made the device closed in 2006.

Polymer injection

Polymer injection (and similar procedures) aimed to add bulk to the gastro-oesophageal junction, thereby narrowing it, to reduce reflux. The most popular of these procedures was Enteryx.166 The procedure entailed endoscopic injection of 5–8 mL of a bioinert polymer into the plane between the circular and longitudinal muscle of the distal oesophagus, to create a ring of polymer just above the gastro-oesophageal junction. Initial reports suggested success rates of 70–80% at 12 months follow-up.166 However, the results from a randomised sham-controlled trial were also unimpressive, with no difference in acid exposure (11.2% vs. 12.7%) at 3 months follow-up. This trial also demonstrated a significant placebo effect, with 41% of the sham-treated patients able to cease proton-pump inhibitor medication, compared to 68% of the treated group.172 Unfortunately, there were also some catastrophic complications, including four deaths,173,174 and the manufacturer withdrew the procedure. A similar product, the Gatekeeper reflux repair system, was also withdrawn from clinical use.175

Endoscopic suturing

The EndoCinch (Bard Endoscopic Technologies, Murray Hill, NJ) procedure entailed the endoscopic placement of two 3-mm-deep sutures into adjoining gastric mucosal folds immediately below the gastro-oesophageal junction, to create pleats to narrow this region. The sutures were not deep enough to include the underlying muscle. Case series demonstrated improvements in symptoms and distal oesophageal acid exposure (15.4% to 8.7%).176 However, as with the other endoscopic procedures, reflux was only cured in a minority, and 90% of sutures disappeared within 12 months.177 In a randomised sham-controlled trial, oesophageal acid exposure was similar in the treated and sham groups, and the results of this trial did not compare well with the outcomes for laparoscopic antireflux surgery.177

NDO Plicator

The NDO Plicator (NDO Surgical, Mansfield, MA) represented the first attempt to perform a more ‘surgical’ procedure via a transoral approach. It used a flexible overtube that could be retroflexed in the stomach. A screw device penetrated and retracted the gastro-oesophageal junction, and a full-thickness plication of the cardia was fashioned to narrow the gastro-oesophageal junction. This was secured with a pre-tied pledgeted suture. For the first time, a sham-controlled trial178 actually showed a significant reduction in oesophageal acid exposure (measured by ambulatory pH monitoring) from 10% to 7% at 3 months following treatment. However, acid exposure was not restored to normal in most patients, and the degree of improvement was certainly inferior to the 0–2.5% expected following laparoscopic fundoplication.4,89 At 3 months follow-up, 50% of patients were able to cease proton-pump inhibitor medication compared to 25% of the sham-treated patients. Again, these results are inferior to those of laparoscopic antireflux surgery and it is likely that this procedure does not create a true fundoplication. The company making this device closed in 2008.

Endoscopic fundoplication

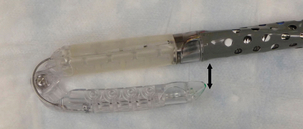

Unlike the previous procedures, the EsophyX (Endogastric Solutions, Washington) procedure aims to construct an actual fundoplication.179 This procedure requires general anaesthesia and two operators. A standard endoscope is passed through the device (Figs 13.13 and 13.14) and both are passed transorally into the stomach. The endoscope is retroflexed for vision and a screw device anchors tissue at the gastro-oesophageal junction to retract it caudally. A plastic arm (tissue mould) then compresses the fundus against the side of the oesophagus, and polypropylene fasteners are passed between the oesophagus and the gastric fundus to anchor these structures. Multiple fasteners are applied to fashion a 200–300° anterior partial fundoplication.

Figure 13.13 Operating handle for the EsophyX device for endoluminal anterior partial fundoplication.

Figure 13.14 Distal end of EsophyX device. The tip is sited within the stomach and the shaft in the distal oesophagus. The two components close together as indicated to allow the fasteners to be deployed.

Some cases series report promising short-term outcomes, with claimed success rates of 55–80% at up to 2 years follow-up,179,180 but lower success rates for normalisation of oesophageal acid exposure.179 In general, however, this procedure has been restricted to patients with milder degrees of reflux, i.e. no circumferential ulcerative oesophagitis, Barrett’s oesophagus, hiatus hernia ≥ 3 cm or a body mass index > 30. Whilst most patients recover uneventfully, significant complications have also been reported, including bleeding, pneumoperitoneum and oesophageal perforation. Cadière et al.179 reported a series of 86 patients, followed for 12 months. Eighty-one per cent of patients were not using proton-pump inhibitor medication and 56% claimed cure of their reflux. Postoperative pH monitoring, however, revealed that only 37% of patients had a normal pH study following the EsophyX procedure. The results from this experience suggest that in some patients a fundoplication can be constructed, but perhaps not reliably. Other experience is also less than satisfactory. We recently reported a three-centre experience of 19 EsophyX procedures.181 Only five patients were able to stop antireflux medication, whereas 10 underwent laparoscopic fundoplication within 12 months for a failed EsophyX procedure. Overall, the published literature suggests EsophyX is much less effective than any type of partial fundoplication,4 and less than half of patients treated have objective evidence that reflux has been cured.

A similar approach has also been pursued by Medigus (Omer, Israel), who developed a stapling endoscope for the construction of an anterior partial fundoplication.182 However, clinical trial data are yet to be reported, and this device has not been commercialised. For now it still seems that a durable partial fundoplication cannot be reliably fashioned using an endoscopic approach. This could be because the endoscopic approaches are unable to repair a hiatus hernia and also fail to anchor the fundus to the diaphragm, both important steps for constructing a stable partial fundoplication.

References

1. Watson, D.I., Lally, C.J., Incidence of symptoms and use of medication for gastro-esophageal reflux in South Australia. World J Surg 2009; 33:88–94. 18949510

2. Thompson, W.E., Heaton, K.W., Heartburn and globus in apparently healthy people. Can Med Assoc J 1982; 126:46–48. 7059872

3. Lord, R.V.N., Law, M.G., Ward, R.L., et al, Rising incidence of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in men in Australia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1998; 13:356–362. 9641297

4. Watson, D.I., Jamieson, G.G., Pike, G.K., et al, A prospective randomised double blind trial between laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and anterior partial fundoplication. Br J Surg 1999; 86:123–130. 10027375 The first published randomised trial to compare an anterior partial fundoplication with the Nissen procedure.

5. Watson, D.I., Pike, G.K., Baigrie, R.J., et al, Prospective double blind randomised trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication with division and without division of short gastric vessels. Ann Surg 1997; 226:642–652. 9389398 A randomised trial of 102 patients who underwent a total fundoplication with or without division of the short gastric vessels.

6. Ireland, A.C., Holloway, R.H., Toouli, J., et al, Mechanisms underlying the antireflux action of fundoplication. Gut 1993; 34:303–308. 8472975

7. Dent, J., Australian clinical trials of omeprazole in the management of reflux oesophagitis. Digestion 1990; 47:69–71. 2093019

8. Watson, D.I., Mathew, G., Pike, G.K., et al, Comparison of anterior, posterior and total fundoplication using a viscera model. Dis Esophagus 1997; 10:110–114. 9179480

9. Bate, C.M., Keeling, P.W., O’Morain, C., et al, Comparison of omeprazole and cimetidine in reflux oesophagitis: symptomatic, endoscopic, and histological evaluations. Gut 1990; 31:968–972. 2210463

10. Hetzel, D.J., Dent, J., Reed, W.D., et al, Healing and relapse of severe peptic esophagitis after treatment with omeprazole. Gastroenterology. 1988;95(4):903–912. 3044912

11. Kuipers, E.J., Lundell, L., Klinkenberg-Knol, E.C., et al, Atrophic gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with reflux esophagitis treated with omeprazole or fundoplication. N Engl J Med 1996; 334:1018–1022. 8598839

12. Driman, D.K., Wright, C., Tougas, G., et al, Omeprazole produces parietal cell hypertrophy and hyperplasia in humans. Dig Dis Sci 1996; 41:2039–2047. 8888719

13. Verlinden, M., Review article: a role for gastrointestinal prokinetic agents in the treatment of reflux oesophagitis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1989; 3:113–131. 2491462

14. Waring, J.P., Hunter, J.G., Oddsdottir, M., et al, The preoperative evaluation of patients considered for laparoscopic antireflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90:35–38. 7801945

15. Francis, D.O., Goutte, M., Slaughter, J.C., et al, Traditional reflux parameters and not impedance monitoring predict outcome after fundoplication in extraesophageal reflux. Laryngoscope 2011; 121:1902–1909. 22024842

16. Bischof, G., Feil, W., Riegler, M., et al, Peptic esophageal stricture: is surgery still necessary? Wei Klin Wochenschr 1996; 108:267–271. 8686319

17. Ratnasingam, D., Irvine, T., Thompson, S.K., et al, Laparoscopic antireflux surgery in patients with throat symptoms: a word of caution. World J Surg 2011; 35:342–348. 21052996

18. Farrell, T.M., Smith, C.D., Metreveli, R.E., et al, Fundoplication provides effective and durable symptom relief in patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Surg 1999; 178:18–21. 10456696

19. Ortiz, E.A., Martinez de Haro, L.F., Parrilla, P., et al, Conservative treatment versus antireflux surgery in Barrett’s oesophagus: long-term results of a prospective study. Br J Surg 1996; 83:274–278. 8689188

20. Ortiz, A., De Maro, L.T., Parrilla, P., et al, 24-h pH monitoring is necessary to assess acid reflux suppression in patients with Barrett’s oesophagus undergoing treatment with proton pump inhibitors. Br J Surg 1999; 86:1472–1474. 10583299

21. Sagar, P.M., Ackroyd, R., Hosie, K.B., et al, Regression and progression of Barrett’s oesophagus after antireflux surgery. Br J Surg 1995; 82:806–810. 7627517

22. Gurski, R.R., Peters, J.H., Hagen, J.A., et al, Barrett’s esophagus can and does regress after antireflux surgery: a study of prevalence and predictive features. J Am Coll Surg 2003; 196:706–712. 12742201

23. Ackroyd, R., Brown, N.J., Davis, M.F., et al, Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut 2000; 47:612–617. 11034574

24. Ackroyd, R., Tam, W., Schoeman, M., et al, Prospective randomised controlled trial of argon plasma coagulation ablation versus endoscopic surveillance of Barrett’s oesophagus in patients following antireflux surgery. Gastrointest Endosc 2004; 59:1–7. 14722539

25. Goers, T.A., Leão, P., Cassera, M.A., et al, Concomitant endoscopic radiofrequency ablation and laparoscopic reflux operative results in more effective and efficient treatment of Barrett esophagus. J Am Coll Surg 2011; 213:486–492. 21784666

26. Bright, T., Watson, D.I., Tam, W., et al, Randomized trial of argon plasma coagulation vs. endoscopic surveillance for Barrett’s oesophagus following antireflux surgery – late results. Ann Surg 2007; 246:1016–1020. 18043104

27. Behar, J., Sheahan, D.G., Biancani, P., Medical and surgical management of reflux oesophagitis, a 38-month report on a prospective clinical trial. N Engl J Med 1975; 293:263–268. 237234

28. Spechler, S.J., Comparison of medical and surgical therapy for complicated gastroesophageal reflux disease in veterans. N Engl J Med 1992; 326:786–792. 1538721 The first large prospective randomised trial to compare medical with surgical therapy for gastro-oesophageal reflux.

29. Parrilla, P., Martinez de Haro, L.F., Ortiz, A., et al, Long-term results of a randomized prospective study comparing medical and surgical treatment of Barrett’s esophagus. Ann Surg 2003; 237:291–298. 12616111

30. Lundell, L., Miettinen, P., Myrvold, H.E., et al, Continued (5-year) followup of a randomized clinical study comparing antireflux surgery and omeprazole in gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Am Coll Surg 2001; 192:172–181. 11220717

31. Lundell, L., Miettinen, P., Myrvold, H.E., et al, Long-term management of gastroesophageal reflux disease with omeprazole or open antireflux surgery: results of a prospective, randomized clinical trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12:879–887. 10958215

32. Mehta, S., Bennett, J., Mahon, D., et al, Prospective trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease: seven-year follow-up. J Gastrointest Surg 2006; 10:1312–1316. 17114017

33. Mahon, D., Rhodes, M., Decadt, B., et al, Randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication compared with proton-pump inhibitors for treatment of chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux. Br J Surg 2005; 92:695–699. 15898130 The first randomised trial of proton-pump inhibitor versus laparoscopic antireflux surgery.

34. Anvari, M., Allen, C., Marshall, J., et al, A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease: one-year follow-up. Surg Innov 2006; 13:238–249. 17227922

35. Anvari, M., Allen, C., Marshall, J., et al, A randomized controlled trial of laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication versus proton pump inhibitors for the treatment of patients with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): 3-year outcomes. Surg Endosc 2011; 25:2547–2554. 21512887