Treatment of early oesophageal cancer

Definition of early oesophageal cancer and relevant pathology

A cancer in the oesophagus is considered ‘early’ if it is contained within the superficial components of the epithelial lining and there is no lymph node involvement. Using the latest American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging criteria, for both SCC and AC, this would include oesophageal cancer diagnosed at stages 0 or IA.1 Stage 0 includes Tis or high-grade dysplasia (HGD) of the epithelium. This had previously been called carcinoma in situ.2 Stage I relates to the depth of invasion into the oesophageal wall with no lymph nodes involved. This stage includes cancers that are T1–2. However, the pathological stage can only be diagnosed after the resection of the oesophagus. The deeper the invasion into the mucosa and submucosa, the higher the incidence of nodal metastasis, so that a clear definition of the T stage is vital when assessing a patient thought to have an ‘early’ oesophageal cancer.

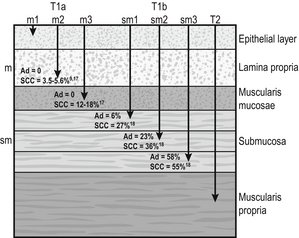

The T stage can be subclassified into cancer that is restricted to the mucosa, T1a, and to the submucosa, T1b. Within the mucosa (T1a) the invasion can be subclassified into cancers confined to the epithelium (m1), the lamina propria (m2) and the muscularis mucosae (m3).1 Patients with Barrett’s oesophagus may have duplication of the muscularis mucosae but they are still m3 so long as the muscularis mucosae has not been breached. Cancers infiltrating into the submucosa (T1b) may be subclassified into sm1 (inner third), sm2 (middle third) and sm3 (outer third)1 (Fig. 6.1).

Figure 6.1 Anatomical layers of the oesophagus with risk of lymph node involvement. Ad, adenocarcinoma.

The relevance of subclassification relates to the risk of lymphatic invasion. The lymphatic network in the oesophagus is concentrated in the submucosa; however, there are lymphatic channels in the lamina propria. From studies of patients that have had a resection for T1 cancer it is clear that there is a higher risk of nodal involvement if it invades to T1b level compared with T1a cancers.3–17 There are subtle differences between patients with AC and SCC. HGD in Barrett’s epithelium and in squamous epithelium as well as AC or SCC involving m1 do not have nodal disease.3–5,10,11,13,17 AC invading to m2 and m3 do not have lymph node metastasis.3–6,8

However, for patients with SCC to the m2 level, there have been reports of patients with positive lymph nodes found in 3.3%9 and 5.6%,17 although this is not clear as others have reported no evidence of positive nodes at this level.10–15 If the tumour extends to m3, the node-positive rate has been reported to be 18% in a large single-centre series17 and 12.2% in a review of 1740 patients with early SCC.9 The histological finding of lymphatic invasion in association with m3 invasion has been shown to increase the risk of positive lymph nodes11,17 from 10% to 42%.17

For either AC or SCC invading the submucosa (T1b), the potential for nodal metastasis increases from sm1 to sm3.18 A review of articles from 1980 to 2009 reported an overall lymph node-positive rate of 37%, with the incidence higher for SCC (45%) than AC (26%). For sm1 disease, the presence of lymphatic invasion on histology increases the risk of positive lymph nodes from 11% to 65%.11 The incidence of node positivity was higher in patients with SCC compared with AC at sm1 (27% vs. 6%) and sm2 (36% vs. 23%) levels, but the same at sm3 (55% vs. 58%).18 The implication may be that SCC is more biologically aggressive at presentation.

For patients with T1b cancers the optimal oncological therapy is an oesophagectomy with a systematic lymphadenectomy. There may be ‘low-risk’ sm1 patients with AC that might be considered for endoscopic therapies but it is not so clear for patients with SCC. The ‘low-risk’ AC is a patient with a well-differentiated cancer with no evidence of lymphovascular invasion.5,8 One report of 85 patients with T1 AC analysed four subgroups with differing nodal involvement and prognosis. Patients with T1a disease had no nodes and 100% disease-specific survival (DSS). Those with T1b cancers were split into three groups: well differentiated and no lymphatic/vascular invasion (LVI) – 4% nodal involvement, 85% 5-year DSS; poorly differentiated and no LVI – 22% nodal involvement, 65% 5-year DSS; and any cancer with LVI – 46% nodal involvement, 40% 5-year DSS.5

The reason for the difference between histological subtypes is not clear but explanations include: fewer lymphatic channels in the lamina propria in the lower oesophagus (where AC occurs7) and SCC is more biologically aggressive at an earlier stage.18

Investigations

Endoscopic assessment

Patients with the diagnosis of HGD or intramucosal carcinoma in Barrett’s epithelium should have the endoscopy repeated according to a protocol of four quadrant biopsies 1 cm apart and targeted biopsies of macroscopically suspect lesions.19 The pathology should be reviewed by two independent experienced gastrointestinal pathologists to confirm the diagnosis.

Squamous neoplasia

Patients with a diagnosis of HGD in squamous epithelium or suspected early invasive carcinoma should have the endoscopy repeated to clearly establish the extent of the disease process. The use of Lugol’s iodine staining is recommended to allow targeted biopsies of the non-stained areas.20 Knowledge of the extent of the mucosal change is important when planning treatment as very long segments may only be treated with oesophagectomy. If endoscopic therapy is to be considered, the non-stained areas outline the targets for endoscopic resection or ablation.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR)

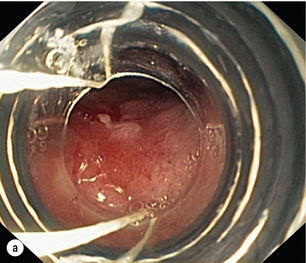

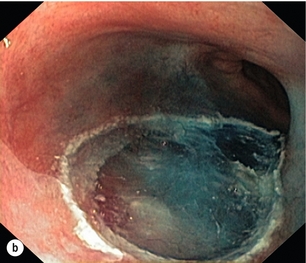

This is the removal of the mucosa and a varying degree of submucosa. In patients with HGD or suspected intramucosal carcinoma (IMC) this is the most accurate and definitive method of confirming the histology and defining the T stage of abnormal mucosa or any mucosal lesion.21,22 Endoscopic mucosal resection offers better T staging than endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and computed tomography (CT) scanning,23 and will alter the histological grade or the local T stage of mucosal neoplasia in up to 48% of patients,24 thereby potentially influencing the management (Fig. 6.2).

Figure 6.2 Intramucosal carcinoma in a segment of Barrett’s epithelium before (a) and after (b) endoscopic mucosal resection.

Patients with squamous epithelial neoplasia can have abnormailites targeted with EMR. A study of 51 patients who had an EMR for squamous HGD reported 31% to be m2/3, with over a third of these lesions being flat such that they were unrecognisable from HGD alone.25 This also stresses the need for extensive mapping biopsies of squamous epithelial neoplasia, using Lugol’s iodine, if endoscopic therapies are to be considered.

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

This technique is widely used in Asia, notably by the Japanese, for definitive treatment of patients with superficial gastric cancer. It has been used for squamous neoplasia because it entails a formal dissection in the submucosal plane to remove a complete segment of mucosa and submucosa. The advantage is that the whole abnormal segment of oesophagus may be removed en bloc26,27 and there is less likelihood of margins being involved when compared with EMR in the tubular oesophagus.26,28

Imaging

The accuracy of differentiating the layers of the mucosa has been reported to be 85–100% with the use of the higher frequency (15 and 20 MHz) miniprobes;29 however, the numbers are small and these are expert centres. In general practice this differentiation is not good enough to stratify patients to allow decisions relating to endoscopic therapy and oesophagectomy.6 It may be the value of EUS will be for examination of the local lymph nodes and, if considered suspicious, achieving confirmation with fine-needle aspiration.29 When the tumour is considered to be invasive there is a role for anatomical imaging with CT scanning and functional imaging with positron emission tomography (PET) for formal staging.30

Management of early oesophageal cancer

Oesophageal resection

In a review from 2007 of 29 series of patients having a resection for Barrett’s HGD, it was reported that cancer was found in the specimen in 37% of cases with 60% of this group (22% of the total) invading beyond the mucosa.31 They reported no downward trend in this incidence in recent years. This review consists of a number of older series where patients were not likely to have had a systematic approach to biopsy of the Barrett’s mucosa, and none of the patients underwent an EMR of abnormal mucosa, which would offer a better histological assessment with improved T staging. The factors that have been reported to be associated with a coexisting cancer in HGD are a visible lesion, ulceration and HGD at multiple levels.32,33 The potential for an unexpected finding of an invasive cancer is now lower than previously reported.

For patients confirmed to have squamous dysplasia the potential for the development of an invasive cancer increases with time. For low-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (LGIN), the risk at 3.5 and 13.5 years has been reported as 5% and 24%, respectively, for moderate-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (MGIN) 27% and 50%, respectively, and for high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia (HGIN) 65% and 74%, respectively.34 Definitive treatment should be directed towards HGD with careful observation in patients with lower levels of dysplasia.

Although patients with HGD do not have an invasive cancer the risk is removed completely with an oesophagectomy. In the short term the potential for short-term cancer mortality is very low, so it is important that the surgical outcomes are optimal. In the last decade operative mortality for oesophageal resection in high-volume centres has been reported to be 2–4%, with rates of 0–1% when the resection was for HGD or IMC.31,35 The long-term disease-specific survival (DSS) following an oesophagectomy for HGD should be 100% and for early invasive oesophageal cancer (stage I) for AC 80–90%7,36 and SCC 3-year survival of 85%37 and 5-year DSS of 53–77%38,39 have been reported.

Because of the associated high morbidity, mortality and effects on the quality of life, alternatives to a traditional oesophagectomy and lymphadenectomy have been explored. For lesser procedures to be successful a degree of predictability of the lymph node drainage is necessary. For stage I disease, in one study, patients with AC had the majority of positive nodes below the tracheal bifurcation, locally associated with the primary cancer in all but 2%. For SCC the nodal site was not predicable, with the positive nodes widely distributed in the chest and upper abdomen.7

Thus, for early AC this had led to groups attempting variations from a major resection. Two variations described for patients with Barrett’s HGD and IMC are a limited resection of the oesophagogastric junction40 and vagal-sparing oesophagectomy.41 The resection of the oesophagogastric junction with jejunal interposition (Merendino operation) is performed using a transabdominal approach, with splitting of the oesophageal hiatus. The dissection can be carried out, through the hiatus, to the level of the tracheal bifurcation incorporating a lower mediastinal and upper abdominal lymphadenectomy with or without preservation of the vagal innervation of the distal stomach. Following resection of the distal oesophagus, cardia and proximal stomach, the gastrointestinal continuity is restored by means of interposition of an isoperistaltic pedicled jejunal loop to prevent postoperative reflux.40 The outcome of over 100 procedures for early Barrett’s cancer reported similar outcomes in terms of long-term survival compared with a radical oesophagectomy. The advantages were lower peri- and postoperative morbidity, and a good postoperative quality of life. The procedure has been reported to be technically challenging and requires attention to detail to achieve good long-term functional results.40

Vagal-sparing oesophagectomy (VSO) has recently been popularised for HGD and T1a adenocarcinoma of the lower oesophagus. Reconstruction is via the use of a gastric tube or colon pull-up. The authors report a reduction in side-effects attributed to the vagal resection that occurs with a more aggressive resection.41 The operative mortality has been reported to be 2% with major complications in 35% of patients, but there was a reduction, but not abolition, of diarrhoea and dumping symptoms.41

Alternative approaches are the transhiatal approach and minimally invasive approaches to an oesophageal resection. The transhiatal approach has been reported to reduce respiratory complications compared with an open oesophagectomy.42,43 Although suitable for AC the transhiatal approach does not address the issue of the unpredictable lymphatic drainage of SCC, so that a systematic lymphadenectomy should be performed with the benefits of an upper and cervical mediastinal lymphadenectomy being weighed against the added morbidity.7,10,44

Minimally invasive approaches to oesophagectomy will allow resection of the primary cancer and a lymphadenectomy. Reports suggest there may be a reduction in respiratory complications when the chest and abdominal components are performed using minimally invasive approaches.45–47 The approach has also been described allowing a dissection of the mediastinum, as required for SCC.48

Oesophagectomy does have an effect on the quality of life of patients. There have been reports that claim the long-term functional outcomes from a resection are at least equivalent to the general population.49,50 However, despite their conclusions there are patients that have significant gastro-oesophageal reflux (59–68%), dysphagia (38%), dumping (15%), diarrhoea (55%) and bloating (45%).49,50 Others have confirmed the higher incidences of functional symptoms such as dumping syndrome, bloat, reflux and diarrhoea, which do not settle in the long term.51

Endoscopic therapy

Endoscopic mucosal resection

Aside from diagnosis and T-stage assessment this technique may be therapeutic, removing the lesion completely. The techniques used for this procedure result in piecemeal segments of mucosa and submucosa being removed. Techniques such as ‘inject, suck and cut’(endoscopic resection cap, ER-cap) and ‘band and snare’ (endoscopic resection multiband mucosectomy, ER-MBM) are used, and have been shown to provide the pathologist with equivalent and adequate depths of mucosa and submucosa.52 A randomised study assessing the two techniques has shown that ER-cap produces specimens of larger diameter but with equivalent amount of submucosa. ER-MBM was quicker, less costly and had a similar safety profile.53 Short segments of neoplastic epithelium (Barrett’s or squamous) can be completely removed in up to 80–94% of patients.54 The recurrence rate increases with the length of follow-up because the treatment may not deal with all the Barrett’s epithelium, some of which may not be visible.3 When EMR alone is used to eradicate the Barrett’s segment the complete eradication rate may reach 97%, but the incidence of stricture increases up to 37%.55 It is likely the optimal use of EMR will be in combination with Barrett’s ablative techniques. The technique has been shown to be safe, with a low incidence of complications such as bleeding (0–1.5%), perforation (0.3–0.5%) and stricture formation if segmental regions are treated (7–9%).

For squamous epithelial neoplasia the results from EMR are similar to Barrett’s neoplasia, with rates of recurrence reported to be 10–26%.26,56,57 When examining the recurrence rate in association with depth of invasion, the incidence has been reported to be 13–18% in lesions that are m1/2.57

Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD)

This is a technically demanding procedure and, aside from the risk of perforation, there is a higher incidence of stricture formation when compared with EMR because of the deeper resection plane and larger segments removed. This technique has not been readily taken up in the West for the management of Barrett’s neoplasia, although there have been European reports of the technique being used for SCC.56,58 The potential for recurrence of the squamous neoplasia, after ESD, is low at 1–2%.26,59 Bleeding occurs in 10% in larger series; however, this is typically dealt with during the procedure or in the first 24 hours. Perforation occurs in 4–10% and is typically treated with endoscopic clips. Because of the length of segments removed, the stricture rate can be high (6–26%).59

Mucosal ablation

Accepting that EMR and ESD target the high-risk lesions, allowing complete histological assessment, the high-risk mucosa should then be removed or ablated. The technique offering the most promise for mucosal ablation is radiofrequency ablation (RFA), with other options that include photodynamic therapy (PDT) and argon plasma coagulation (APC). PDT is very intensive and only performed in specialist units, so that it has essentially been replaced by APC and RFA. PDT offers a durable remission with replacement by squamous epithelium in 50–80% of patients60 and a risk of recurrence of the HGD in up to 8% of patients.61 The stricture rate can be as high as 36%.61

APC will eradicate the superficial mucosa to a variable depth, allowing complete eradication in 38–99% of patients, with recurrence of 3–16%.62–64 APC has a better ablation rate when compared with PDT.65 For each technique, it is not unusual for the patient to require repeat therapy. Both techniques carry a risk of the development of subsquamous Barrett’s (buried Barrett’s) under the regenerated squamous epithelium, reported to be around 20%.65 This entity has the potential for malignant transformation.66

RFA is a balloon-based radiofrequency device that will ablate the mucosal layer of the tubular oesophagus to a defined depth. There is also a device that will treat distinct residual patches of Barrett’s mucosa. The potential for complete eradication has been reported to be 90% in HGD, 80% in Barrett’s dysplasia and 54% for intestinal metaplasia.67 Residual disease is typically seen as small islands or tongues and can be treated separately. Complete eradication cannot be guaranteed, with newly detected metaplasia at 1 year, seen in up to 26% with 8.5% reported to have dysplasia.68 The stricture rate was 0.4% and the incidence of buried glands much lower than with the other techniques.67 A recent randomised trial comparing stepwise EMR and RFA demonstrated comparable response rates, with fewer sessions and less morbidity in the RFA group.69

There are very few data available relating to the use of RFA for squamous neoplasia. In a study of 29 patients with dysplasia (18), HGD (10) and SCC m1 (1) treated with RFA, after a single treatment at 3 months the complete response rate (CR) was 86%. At 12 months, with further RFA treatments, the CR was 83% (14% low-grade dysplasia).70 For both histological entities, it is likely that there may be a role for EMR followed by RFA in selected patients.

Results from endoscopic therapy for early oesophageal cancer

For HGD or IMC/T1a carcinoma in Barrett’s epithelium, the group in Weisbaden, Germany, assess 80 patients and treat 60–70 with endoscopic therapy per year.71 They report complete resection rates of 97%. The median follow-up period was 64 months and there was a metachronous lesion in 21%. The higher risk for recurrence is in patients who have piecemeal resection, long-segment Barrett’s, no ablation of the Barrett’s (PDT performed selectively), multifocal neoplasia and time to complete removal of the identified lesion of more than 10 months. Importantly, this group highlight the need to intensively follow patients. Surgery was required in 3.7% because of failure of endoscopic therapy to clear the disease.71 Others have reported the development of a new metachronous cancer following ablative therapy to occur in 6–20%.72,73

In a review of studies assessing the role of Barrett’s ablation (no RFA) compared with patients observed with HGD, the long-term cancer risk was reduced by ablation but not abolished. After ablation the risk of malignant change was 16.66/1000 patient-years compared with 65.8/1000 patient-years for observation. The frequency of recurrence of intestinal metaplasia was 0–68%.74 In a small study of 31 patients, using RFA following EMR, it was possible to eradicate the high-risk mucosa in patients with early AC (16), HGD (12) or LGD (3). At median 21 months, all dysplasia was eradicated with a 9% stricture rate.75

Two studies of institutional comparisons between endoscopic therapy (ET) and resection for HGD and/or IMC have shown no mortality for either treatment, with little to no morbidity for ET but early morbidity rates around 39% in the resection group.73,76 Equivalent cancer-specific survivals were reported. However, a new metachronous primary neoplastic lesion occurred in 20%73 and 12%76 of the endotherapy groups. These were usually treated endoscopically. There has been one case-controlled comparative study assessing oesophagectomy compared with EMR and ablation in patients with intramucosal adenocarcinoma (T1a).77 The resection group had a median follow-up of 4 years with no tumour recurrence. The major complication rate was 32% and 90-day mortality 2.6%. Following endoscopic therapy there was no major morbidity or mortality, and 6.6% of patients needed further local therapy during the median follow-up time of 3.7 months.77

The use of EMR has been reported in a cohort of 21 patients having endoscopic therapy for ‘low-risk’ T1b adenocarcinoma. Low risk was defined as: invasion of the upper sm1; absence of lymphatic/vascular invasion; grade I/II; polypoid or flat lesion (not ulcerated). APC was used for Barrett’s ablation in 73%. At a median follow-up of 62 months there was an initial 90% complete resection rate with 28% recurrence of metachronous carcinoma. There were no tumour-related deaths. For this subset of patients one needs to consider this treatment as experimental and more suitable for patients not considered to be surgical candidates until more data are available.78

Squamous cell carcinoma

The majority of the studies are from Japan using EMR or ESD.9,26,27,59 There is one series of ESD from Italy58 and one from Germany using EMR.56 A study assessing EMR in 351 patients reported a 5-year disease-free survival of 98%. At a median follow-up of 9 months the local recurrence rate was 2% in patients with m1/2 disease, 7% with m3/sm1 and 7% with sm2/3. The only patients who developed metastasis had sm1/2 disease.79 The largest single-centre series has 300 patients with m1–3 (m3 15%) disease, in whom 184 had EMR and 116 ESD.26 A positive margin was seen in 3% who had ESD and 22% who had an EMR. However, the stricture rate was 17% for ESD compared with 9% who had an EMR. Local recurrence was 10% after EMR in patients that had a piecemeal resection. Recurrence may also manifest as recurrent nodes or systemic disease. This is more likely to occur in patients who had lesions that were m3 or submucosal treated with EMR or ESD.27,56,59

Definitive radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy

Most often this modality is offered when patients are unfit for resection or refuse an operation. In patients with invasive SCC (stage II/III), there is evidence from randomised trials for the use of definitive chemoradiation (CRT)80 over radiation (RT) alone and for definitive chemoradiation as replacement for resection alone.81 For adenocarcinoma, there are no data from randomised trials for the use of definitive radiation with or without chemotherapy. For adenocarcinoma the evidence is extrapolated from the histological responses that may occur in the primary tumour in phase II and III trials of neoadjuvant therapy followed by resection of the oesophagus.82

A Cochrane analysis of CRT compared with RT alone reports the value of CRT to be a reduction in local persistence/recurrence of 12%.83 Assessing local control of disease following definitive CRT for stage I disease, two studies from Japan report initial complete responses of 93%84 and 87%.85 The incidence of recurrence after CRT has been reported to be 20–30%.38,84 Salvage may be possible with EMR or resection.38,84 The more recent studies examining outcomes from CRT in patients with stage I SCC have reported 3-year DSS of 85%,37 4-year DSS of 80%86 and 5-year DSS of 77%84 and 76%.38 The 5-year DSS survival for T1a was 84% compared with 50% for patients who were T1b.38

There has been one institutional study that has compared the outcomes from CRT with a three-field oesophagectomy for stage I SCC with definitive CRT.37 Resection or definitive CRT was offered to patients who had clinical stage I disease, who were not considered candidates for endoscopic therapy (disease > 5 cm and more than two-thirds of the circumference). There was a bias towards CRT for the elderly and longer lesions. In the 54 patients who had CRT there was a complete endoscopic response in 53. Local recurrence occurred in 21%. Primary resection had a complication rate of 34%, some very serious. The 1- and 3-year disease-specific survivals were 98.1% and 88.75%, respectively, for CRT and 97.4% and 85.5%, respectively, for oesophagectomy. Adjusting for age, sex and tumour size, the hazard ratio for CRT for overall survival was 0.95 (95% confidence interval 0.37–2.47).37

References

1. Edge S.B., Byrd D.R., Compton C.C., et al, eds. AJCC cancer staging manual, 7th ed., New York: Springer, 2009.

2. Rice, T.W., Blackstone, E.H., Rusch, V.W., 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(7):1721–1724. 20369299

3. Larghi, A., Lightdale, C.J., Memeo, L., et al, EUS followed by EMR for staging of high-grade dysplasia and early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62(1):16–23. 15990814

4. Buskens, C.J., Westerterp, M., Lagarde, S.M., et al, Prediction of appropriateness of local endoscopic treatment for high-grade dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma by EUS and histopathologic features. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60(5):703–710. 15557945

5. Barbour, A.P., Jones, M., Brown, I., et al, Risk stratification for early esophageal adenocarcinoma: analysis of lymphatic spread and prognostic factors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(9):2494–2502. 20349213

6. Griffin, S.M., Burt, A.D., Jennings, N.A., Lymph node metastasis in early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):731–737. 21997815

7. Stein, H.J., Feith, M., Bruecher, B.L., et al, Early esophageal cancer: pattern of lymphatic spread and prognostic factors for long-term survival after surgical resection. Ann Surg. 2005;242(4):566–575. 16192817

8. Sepesi, B., Watson, T.J., Zhou, D., et al, Are endoscopic therapies appropriate for superficial submucosal esophageal adenocarcinoma? An analysis of esophagectomy specimens. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(4):418–427. 20347733

9. Kodama, M., Kakegawa, T., Treatment of superficial cancer of the esophagus: a summary of responses to a questionnaire on superficial cancer of the esophagus in Japan. Surgery. 1998;123(4):432–439. 9551070

10. Fujita, H., Sueyoshi, S., Yamana, H., et al, Optimum treatment strategy for superficial esophageal cancer: endoscopic mucosal resection versus radical esophagectomy. World J Surg. 2001;25(4):424–431. 11344392

11. Tajima, Y., Nakanishi, Y., Ochiai, A., et al, Histopathologic findings predicting lymph node metastasis and prognosis of patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma: analysis of 240 surgically resected tumors. Cancer. 2000;88(6):1285–1293. 10717608

12. Hölscher, A.H., Bollschweiler, E., Schröder, W., et al, Prognostic impact of upper, middle, and lower third mucosal or submucosal infiltration in early esophageal cancer. Ann Surg. 2011;254(5):802–808. 22042472

13. Endo, M., Yoshino, K., Kawano, T., et al, Clinicopathologic analysis of lymph node metastasis in surgically resected superficial cancer of the thoracic esophagus. Dis Esophagus. 2000;13(2):125–129. 14601903

14. Shimada, H., Nabeya, Y., Matsubara, H., et al, Prediction of lymph node status in patients with superficial esophageal carcinoma: analysis of 160 surgically resected cancers. Am J Surg. 2006;191(2):250–254. 16442955

15. Tachibana, M., Hirahara, N., Kinugasa, S., et al, Clinicopathologic features of superficial esophageal cancer: results of consecutive 100 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(1):104–116. 17891442

16. Noguchi, H., Naomoto, Y., Kondo, H., et al, Evaluation of endoscopic mucosal resection for superficial esophageal carcinoma. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2000;10(6):343–350. 11147906

17. Eguchi, T., Nakanishi, Y., Shimoda, T., et al, Histopathological criteria for additional treatment after endoscopic mucosal resection for esophageal cancer: analysis of 464 surgically resected cases. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(3):475–480. 16444191

18. Gockel, I., Sgourakis, G., Lyros, O., et al, Risk of lymph node metastasis in submucosal esophageal cancer: a review of surgically resected patients. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5(3):371–384. 21651355

19. Sampliner, R.E., Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97(8):1888–1895. 12190150

20. Mori, M., Adachi, Y., Matsushima, T., et al, Lugol staining pattern and histology of esophageal lesions. Am J Gastroenterol. 1993;88(5):701–705. 7683176

21. DeMeester, S.R., New options for the therapy of Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma: endoscopic mucosal resection and ablation versus vagal-sparing esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85(2):S747–S750. 18222209

22. Stein, H.J., Feith, M., Surgical strategies for early esophageal adenocarcinoma. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19(6):927–940. 16338650

23. Pech, O., May, A., Gunter, E., et al, The impact of endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography on the TNM staging of early cancer in Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(10):2223–2229. 17032186

24. Moss, A., Bourke, M.J., Hourigan, L.F., et al, Endoscopic resection for Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia and early esophageal adenocarcinoma: an essential staging procedure with long-term therapeutic benefit. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(6):1276–1283. 20179694

25. Shimizu, Y., Kato, M., Yamamoto, J., et al, Histologic results of EMR for esophageal lesions diagnosed as high-grade intraepithelial squamous neoplasia by endoscopic biopsy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63(1):16–21. 16377310

26. Takahashi, H., Arimura, Y., Masao, H., et al, Endoscopic submucosal dissection is superior to conventional endoscopic resection as a curative treatment for early squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72(2):255–264 264.e1–2. 20541198

27. Ono, S., Fujishiro, M., Niimi, K., et al, Long-term outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70(5):860–866. 19577748

28. Saito, Y., Takisawa, H., Suzuki, H., et al, Endoscopic submucosal dissection of recurrent or residual superficial esophageal cancer after chemoradiotherapy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(2):355–359. 18226703

29. Lightdale, C.J., Kulkarni, K.G., Role of endoscopic ultrasonography in the staging and follow-up of esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(20):4483–4489. 16002838

30. Liberale, G., Van Laethem, J.L., Gay, F., et al, The role of PET scan in the preoperative management of oesophageal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30(9):942–947. 15498638

31. Williams, V.A., Watson, T.J., Herbella, F.A., et al, Esophagectomy for high grade dysplasia is safe, curative, and results in good alimentary outcome. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(12):1589–1597. 17909921

32. Tharavej, C., Hagen, J.A., Peters, J.H., et al, Predictive factors of coexisting cancer in Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia. Surg Endosc. 2006;20(3):439–443. 16437272

33. Portale, G., Peters, J.H., Hsieh, C.C., et al, Can clinical and endoscopic findings accurately predict early-stage adenocarcinoma? Surg Endosc. 2006;20(2):294–297. 16333557

34. Wang, G.Q., Abnet, C.C., Shen, Q., et al, Histological precursors of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a 13 year prospective follow up study in a high risk population. Gut. 2005;54(2):187–192. 15647178

35. Low, D.E., Update on staging and surgical treatment options for esophageal cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(5):719–729. 21487832

36. Nigro, J.J., Hagen, J.A., DeMeester, T.R., et al, Occult esophageal adenocarcinoma: extent of disease and implications for effective therapy. Ann Surg. 1999;230(3):433–440. 10493489

37. Yamamoto, S., Ishihara, R., Motoori, M., et al, Comparison between definitive chemoradiotherapy and esophagectomy in patients with clinical stage I esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106(6):1048–1054. 21343920

38. Yamada, K., Murakami, M., Okamoto, Y., et al, Treatment results of chemoradiotherapy for clinical stage I (T1N0M0) esophageal carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64(4):1106–1111. 16504758

39. Igaki, H., Kato, H., Tachimori, Y., et al, Clinicopathologic characteristics and survival of patients with clinical Stage I squamous cell carcinomas of the thoracic esophagus treated with three-field lymph node dissection. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;20(6):1089–1094. 11717009

40. Stein, H.J., Hutter, J., Feith, M., et al, Limited surgical resection and jejunal interposition for early adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;19(1):72–78. 17403461

41. Peyre, C.G., DeMeester, S.R., Rizzetto, C., et al, Vagal-sparing esophagectomy: the ideal operation for intramucosal adenocarcinoma and Barrett with high-grade dysplasia. Ann Surg. 2007;246(4):665–674. 17893503

42. Hulscher, J.B., Tijssen, J.G., Obertop, H., et al, Transthoracic versus transhiatal resection for carcinoma of the esophagus: a meta-analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72(1):306–313. 11465217

43. Hulscher, J.B., van Sandick, J.W., de Boer, A.G., et al, Extended transthoracic resection compared with limited transhiatal resection for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1662–1669. 12444180

44. Matsubara, T., Ueda, M., Abe, T., et al, Unique distribution patterns of metastatic lymph nodes in patients with superficial carcinoma of the thoracic oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1999;86(5):669–673. 10361192

45. Luketich, J.D., Alvelo-Rivera, M., Buenaventura, P.O., et al, Minimally invasive esophagectomy: outcomes in 222 patients. Ann Surg. 2003;238(4):486–495. 14530720

46. Palanivelu, C., Prakash, A., Senthilkumar, R., et al, Minimally invasive esophagectomy: thoracoscopic mobilization of the esophagus and mediastinal lymphadenectomy in prone position – experience of 130 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2006;203(1):7–16. 16798482

47. Smithers, B.M., Gotley, D.C., Martin, I., et al, Comparison of the outcomes between open and minimally invasive esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):232–240. 17245176

48. Itami, A., Watanabe, G., Tanaka, E., et al, Multimedia article. Upper mediastinal lymph node dissection for esophageal cancer through a thoracoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(12):2741. 18814011

49. Headrick, J.R., Nichols, F.C., 3rd., Miller, D.L., et al, High-grade esophageal dysplasia: long-term survival and quality of life after esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;73(6):1697–1703. 12078755

50. Chang, L.C., Oelschlager, B.K., Quiroga, E., et al, Long-term outcome of esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia or cancer found during surveillance for Barrett’s esophagus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10(3):341–346. 16504878

51. Moraca, R.J., Low, D.E., Outcomes and health-related quality of life after esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal cancer. Arch Surg. 2006;141(6):545–551. 16785354

52. Abrams, J.A., Fedi, P., Vakiani, E., et al, Depth of resection using two different endoscopic mucosal resection techniques. Endoscopy. 2008;40(5):395–399. 18494133

53. Pouw, R.E., van Vilsteren, F.G., Peters, F.P., et al, Randomized trial on endoscopic resection-cap versus multiband mucosectomy for piecemeal endoscopic resection of early Barrett’s neoplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):35–43. 21704807

54. Peters, F.P., Kara, M.A., Rosmolen, W.D., et al, Stepwise radical endoscopic resection is effective for complete removal of Barrett’s esophagus with early neoplasia: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(7):1449–1457. 16863545

55. Chennat, J., Konda, V.J., Ross, A.S., et al, Complete Barrett’s eradication endoscopic mucosal resection: an effective treatment modality for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal carcinoma – an American single-center experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(11):2684–2692. 19690526

56. Pech, O., Gossner, L., May, A., et al, Endoscopic resection of superficial esophageal squamous-cell carcinomas: Western experience. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(7):1226–1232. 15233658

57. Esaki, M., Matsumoto, T., Hirakawa, K., et al, Risk factors for local recurrence of superficial esophageal cancer after treatment by endoscopic mucosal resection. Endoscopy. 2007;39(1):41–45. 17252459

58. Repici, A., Hassan, C., Carlino, A., et al, Endoscopic submucosal dissection in patients with early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a prospective Western series. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71(4):715–721. 20363414

59. Fujishiro, M., Yahagi, N., Kakushima, N., et al, Endoscopic submucosal dissection of esophageal squamous cell neoplasms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(6):688–694. 16713746

60. Ackroyd, R., Brown, N.J., Davis, M.F., et al, Photodynamic therapy for dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus: a prospective, double blind, randomised, placebo controlled trial. Gut. 2000;47(5):612–617. 11034574

61. Overholt, B.F., Wang, K.K., Burdick, J.S., et al, Five-year efficacy and safety of photodynamic therapy with Photofrin in Barrett’s high-grade dysplasia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66(3):460–468. 17643436

62. Attwood, S.E., Lewis, C.J., Caplin, S., et al, Argon beam plasma coagulation as therapy for high-grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;1(4):258–263. 15017666

63. Ragunath, K., Krasner, N., Raman, V.S., et al, Endoscopic ablation of dysplastic Barrett’s oesophagus comparing argon plasma coagulation and photodynamic therapy: a randomized prospective trial assessing efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2005;40(7):750–758. 16118910

64. Madisch, A., Miehlke, S., Bayerdorffer, E., et al, Long-term follow-up after complete ablation of Barrett’s esophagus with argon plasma coagulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(8):1182–1186. 15754401

65. Kelty, C.J., Ackroyd, R., Brown, N.J., et al, Endoscopic ablation of Barrett’s oesophagus: a randomized-controlled trial of photodynamic therapy vs. argon plasma coagulation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(11–12):1289–1296. 15606390

66. Mino-Kenudson, M., Ban, S., Ohana, M., et al, Buried dysplasia and early adenocarcinoma arising in Barrett esophagus after porfimer-photodynamic therapy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(3):403–409. 17325482

67. Ganz, R.A., Overholt, B.F., Sharma, V.K., et al, Circumferential ablation of Barrett’s esophagus that contains high-grade dysplasia: a U.S. Multicenter Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;68(1):35–40. 18355819

68. Vaccaro, B.J., Gonzalez, S., Poneros, J.M., et al, Detection of intestinal metaplasia after successful eradication of Barrett’s esophagus with radiofrequency ablation. Dig Dis Sci. 2011;56(7):1996–2000. 21468652

69. van Vilsteren, F.G., Pouw, R.E., Seewald, S., et al, Stepwise radical endoscopic resection versus radiofrequency ablation for Barrett’s oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia or early cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Gut. 2011;60(6):765–773. 21209124

70. Bergman, J.J., Zhang, Y.M., He, S., et al, Outcomes from a prospective trial of endoscopic radiofrequency ablation of early squamous cell neoplasia of the esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(6):1181–1190. 21839994

71. Pech, O., Behrens, A., May, A., et al, Long-term results and risk factor analysis for recurrence after curative endoscopic therapy in 349 patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and mucosal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s oesophagus. Gut. 2008;57(9):1200–1206. 18460553

72. Das, A., Singh, V., Fleischer, D.E., et al, A comparison of endoscopic treatment and surgery in early esophageal cancer: an analysis of surveillance epidemiology and end results data. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(6):1340–1345. 18510606

73. Zehetner, J., DeMeester, S.R., Hagen, J.A., et al, Endoscopic resection and ablation versus esophagectomy for high-grade dysplasia and intramucosal adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141(1):39–47. 21055772

74. Wani, S., Puli, S.R., Shaheen, N.J., et al, Esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus after endoscopic ablative therapy: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(2):502–513. 19174812

75. Pouw, R.E., Gondrie, J.J., Sondermeijer, C.M., et al, Eradication of Barrett esophagus with early neoplasia by radiofrequency ablation, with or without endoscopic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(10):1627–1637. 18704598

76. Prasad, G.A., Wu, T.T., Wigle, D.A., et al, Endoscopic and surgical treatment of mucosal (T1a) esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):815–823. 19524578

77. Pech, O., Bollschweiler, E., Manner, H., et al, Comparison between endoscopic and surgical resection of mucosal esophageal adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus at two high-volume centers. Ann Surg. 2011;254(1):67–72. 21532466

78. Manner, H., May, A., Pech, O., et al, Early Barrett’s carcinoma with “low-risk” submucosal invasion: long-term results of endoscopic resection with a curative intent. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(10):2589–2597. 18785950

79. Shimizu, Y., Tsukagoshi, H., Fujita, M., et al, Long-term outcome after endoscopic mucosal resection in patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invading the muscularis mucosae or deeper. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(3):387–390. 12196777

80. Herskovic, A., Martz, K., al-Sarraf, M., et al, Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy compared with radiotherapy alone in patients with cancer of the esophagus. N Engl J Med. 1992;326(24):1593–1598. 1584260

81. Chiu, P.W., Chan, A.C., Leung, S.F., et al, Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing standard esophagectomy with chemoradiotherapy for treatment of squamous esophageal cancer: early results from the Chinese University Research Group for Esophageal Cancer (CURE). J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9(6):794–802. 16187480

82. Geh, J.I., Crellin, A.M., Glynne-Jones, R., Preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemoradiotherapy in oesophageal cancer. Br J Surg. 2001;88(3):338–356. 11260097

83. Wong, R., Malthaner, R., Combined chemotherapy and radiotherapy (without surgery) compared with radiotherapy alone in localized carcinoma of the esophagus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1) CD002092. 16437440

84. Ura, T., Muro, K., Shimada, Y., et al. Definitive chemoradiotherapy may be standard treatment option in clinical stage I esophageal cancer. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 22(317S), 2004. [abstr 4017].

85. Kato, H., Sato, A., Fukuda, H., et al, A phase II trial of chemoradiotherapy for stage I esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9708). Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2009;39(10):638–643. 19549720

86. Kato, H., Tachimori, Y., Watanabe, H., et al, Superficial esophageal carcinoma. Surgical treatment and the results. Cancer. 1990;66(11):2319–2323. 2245387

87. Shitara, K., Muro, K., Chemoradiotherapy for treatment of esophageal cancer in Japan: current status and perspectives. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009;3(2):66–72. 19461908